When Jason Hehir was four years old, he dressed up as Elvis for Halloween. When he got a little older, he started reading a lot of books about JFK. There was a Marilyn Monroe phase.

When he neared middle school in the late '80s: Michael Jordan.

MJ, Elvis, Monroe: Hehir was drawn to mythical celebrities, the kinds of people so famous that they existed more as myths than human beings.

We all do this, in some form, at some point in our lives. I must've been 11 when I sent a Flat Stanley to the United Center, probably thinking, somehow, that Jordan himself would take a picture with my mini-me and mail it back. Instead, I got back a CD of Chicago Bulls Greatest Hits Vol. 3, which I played on a Walkman for the rest of middle school. Coolio, Chic, yes, "Space Jam." I didn't know what "The Shot" was, but I knew all the words to MC Luscious's "Da' Dip."

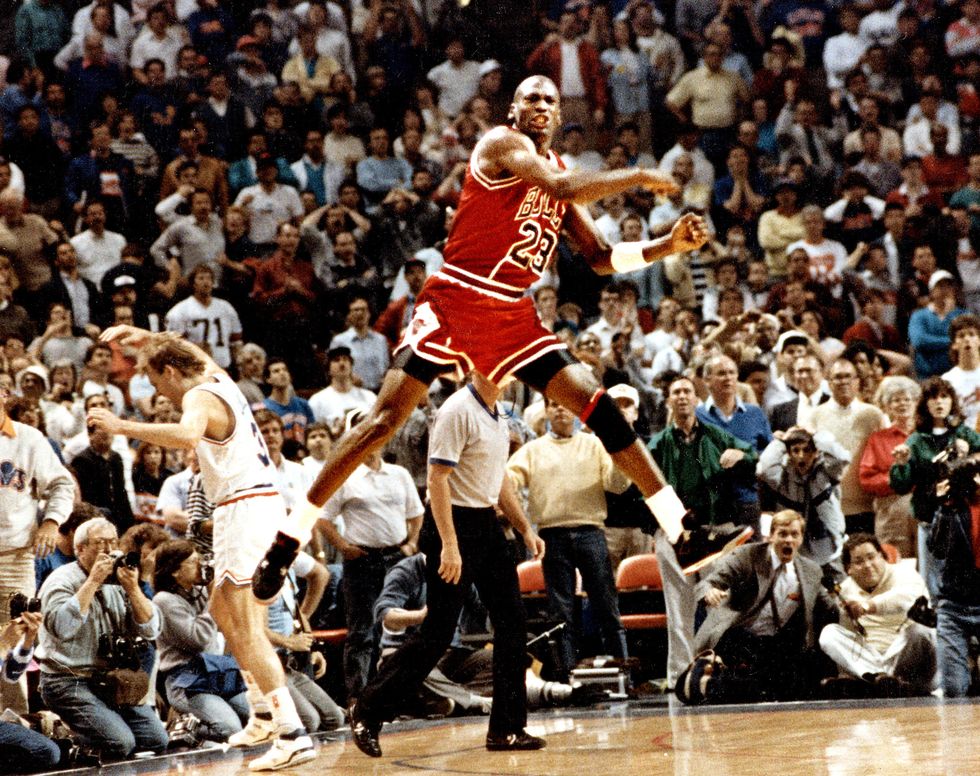

With The Last Dance—ESPN’s 10-part documentary on Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls—Hehir, the director, has given us a meditation on how a mortal becomes an American myth. Yeah, there’s Larry Bird calling Michael Jordan a god. And that stuff is candy to basketball fans. But there are clips of children so starstruck by MJ that they shake, and even full-grown adults who can’t help but throw an arm around Jordan, if only just to say they touched him.

Those moments are about all of us, whomever your Jordan is or was.

Hehir has been fixated on Jordan-esque icons since he donned the Pompadour as a toddler. So you could imagine why The Last Dance is his personal NBA Finals—documenting one of the greatest sports teams of all time, interviewing the men he idolized as a kid. For the project, he got a hold of the legendary footage from the dynasty's 1997-98 season—where a documentary crew followed the team around for its last Jordan-led championship run. Jordan, who rarely gives interviews, finally gave the OK for it all to go forward. So here we are, two episodes a week for the next four Sundays, Jordan, whiskey and cigar nearby, giving us a much-needed sports fix.

Heading into Episodes Three and Four Sunday night, I talked to Hehir (who's currently rushing to wrap up the documentary's final two episodes) about the project. Here are the best parts of what he said.

Hehir learned how to document world-famous celebrities in one of his first projects—directing a Michael Bublé concert documentary.

He was one of the first global megastars that I had been exposed to, and we just had a lot of conversations about the toll that takes, the ups and the downs of fame. I've always really been fascinated by the concept of celebrity and iconization of people. I was Elvis for Halloween when I was four years old, and then I went through a phase where I read all the JFK books and watched all the Marilyn Monroe documentaries. Just people who are thrust into the limelight like that—they must have their humanity stored away somewhere, but it's tough for that to come out the more and more famous you get. So, talking to Michael [Bublé] about that, I think he had just been going through a breakup at that point, and he was just a really human guy when I met him. It was one of many examples of people that I've met who may be famous to people in the tabloids but they still maintain their humanity behind closed doors.

When Hehir was in the fifth grade, he gave a full-blown presentation on the 1987 NBA Slam Dunk contest to a group of confused students.

In fifth grade, there was a multiplication test, and the kid who did it the fastest was gonna get to choose: We could either have class outside at the end of the week, or have an extra gym period. So I won. I said, “Instead of doing either one of those things, can I bring in a video of the 1987 Dunk Contest that just happened, and give a presentation about Michael winning?” So there's 25 fifth-graders watching Terence Danbury and Jerome Kersey and Clyde Drexler like, What are we doing here?

Hehir tried to keep his 10-year-old self in mind while working on The Last Dance.

To look at it through a 10-year-old's eyes as a 43-year-old director, and say, Okay, that's how 10-year olds see him and that's how a lot of adults see him to this day, but there's a human being behind that. So to deconstruct that icon, and see what was inside of them that drove them to the greatness that they achieved. Then examine the price of that level of fame, the toll that that takes on you, your family, and your psyche. I didn't know we would get there with Michael. But very early on in the process, it became evident that he was going to be a lot more open than I had feared.

Michael Jordan could still be the champion of one more sport—deep sea fishing.

I think that the price of that sort of greatness is that you're never satisfied. It's never enough. This is a guy who's driven like a machine to always be the best. His newfound hobby in the last few years is deep sea fishing, and he had an aversion to water for a long time because he had a couple of really scary incidents as a child. What better metaphor than Michael Jordan trying to take on the ocean? He's going to now tame Mother Nature because everything else, everything terrestrial—he's proven that he can figure it out. So the golf course and the Atlantic Ocean are two things that are impossible to beat. But he's certainly gonna try.

Hehir thinks Jordan, after everything, is happy.

I think after his dad's death—and after all the gambling allegations and the examination and scrutiny—once he gave up trying to appear perfect, I think he was much more present and much happier… I was talking to his daughter, and we were discussing his Hall of Fame speech, that he got a lot of criticism for, and she said that she didn't really understand why he was getting the criticism. She called him a couple days later and was like, “Dad, are you okay?” He said, “I'm fine!” He used it as a teaching moment and said, “Listen, you cannot control what other people think of you. You can only control what you say and what you do, and if you're confident in what you say and what you do, then you have to be at peace with that.” I think that's how he approaches life, so I think he's very happy. I think he has bad days like the rest of us, but I don't think he's one of these ex-athletes who sits there brooding, like, What now? Like, no. Michael's in the prime of his life every day he wakes up.

Treat yourself to 85+ years of history-making journalism.

Subscribe to Esquire Magazine

Hehir says some players come off as more muted than others in their interviews because of their humility and pride—not hurt feelings.

I think there's immense pride. And that doesn't exude as well as overjoyed. Although if you want to see the joy, all you gotta do is go back and look at them in the moment. There's almost a solemn pride in all that they accomplished that it's almost reached a level of being sacred. These are also humble guys. It's remarkable to me that the amount of prolific accomplishments these guys have achieved, that they're reticent to speak about their own accomplishments. Scottie Pippen has every right to spout off about how he could've been a superstar for another team and he played in Michael's shadow. That had to grate at him. But good luck trying to get him to say that out loud. Michael, good luck trying to get him to talk about whether or not he thinks that he's the greatest of all time, because he immediately deflects it and talks about the people who came before him.

Jordan called out a "slow white kid" during his first interview for The Last Dance.

When he came in—I met him a few times before—you don't know when the cameras are there, if he's gonna be a little bit reluctant. It was evident immediately that he had come to play. But there was a break in the action. We have a cameraman who's got huge calf muscles. He's very proud of these calf muscles. And he's a huge Jordan fan. So during a break in the action, Jon was walking around, adjusting a light, and Michael and I were talking about the people in the room who were wearing Jordans, and what his favorites are. He pointed at Jon's shoes, and said, “I like those 7’s.” You should've seen Jon's face. Jon's a sneakerhead and a Jordan-head, so this was like nirvana for him. He's walking away and Michael says, “You got big calf muscles. You play football?” Jon said, “No, I play basketball. And he goes, “Oh, big slow white kid, man.” And everyone just started laughing. He wasn't Michael Jordan in that moment—he was just this friendly guy who came in to bust balls.

Jordan challenged Hehir to a bet, after only the second time they met each other:

We're going from Midtown Manhattan to the Jordan Brand Classic, the event that was being held at the Barclay Center, the High School All-Star Game. We get into this SUV, and as soon as we close the door and we drive off, he turns to me and says, “I bet you we see ten pairs of Jordans out the window before we get to this thing.” There was no money on the line. This was just bragging rights—let's play a game while we're in the car. We were driving through Midtown and I'm thinking, Well, we might see a few. By the time we got to the FDR [Drive] from Midtown to head to Brooklyn we had seen four. Then, we got closer and closer to the arena. It's a Jordan Brand Classic Game, so there's thousands of people wearing those. And I was like, “Well that's not fair.” He's like, “Nope.” And he just winked at me. He got in the car and thought, I'm gonna offer a game—and I already know I'm gonna win it.