Perth was founded by Captain James Stirling on Whadjuk country as the capital of the Swan River Colony in 1829.

It was the first free-settler colony in Australia established by private capital. From 1850, convicts began to arrive at the colony in large numbers to build roads and other public infrastructure.

Sir George Murray, letter to Captain James Stirling, 1828:

Amongst your earliest duties will be that of determining the most convenient site for a town to be erected as the future seat of government.

European exploration of the west coast

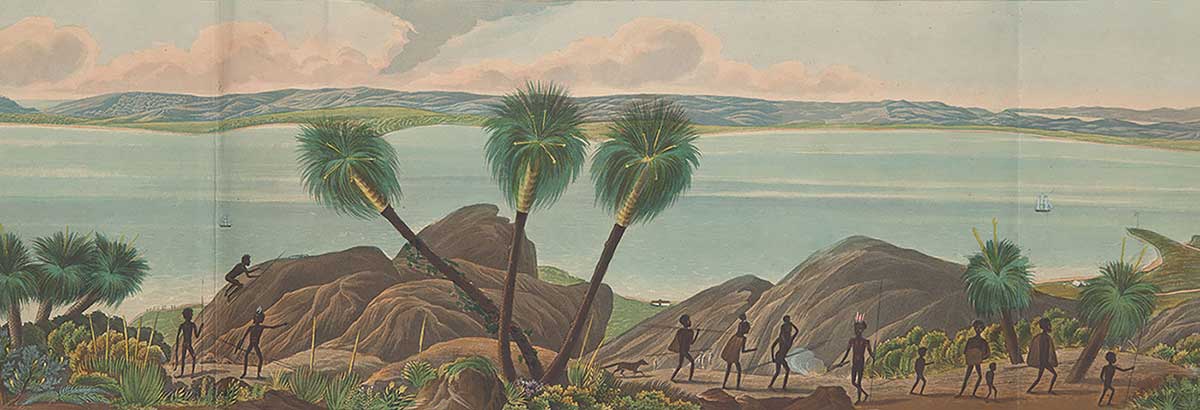

Aboriginal people have lived in the south-western part of Western Australia for at least 47,000 years. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, between 6,000 and 10,000 Noongar people were living in the area.

In October 1616 Dirk Hartog, in the Eendracht, a Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC) ship, became the first European to set foot on the western shores of Australia.

For more than two centuries afterwards Dutch, English and French navigators explored and mapped the west coast. However, no European settlement was established in the west, because the land was seen as inhospitable, offering little economic potential.

It was only when increased French exploration in the region suggested to Britain that France might attempt to establish a colony in the west that the British felt impelled to act.

Claiming western Australia for Britain

On 25 December 1826 Major Edmund Lockyer, in the brig Amity, established a military outpost at King George Sound (now Albany), known locally by Menang Noongar peoples as Kinjarling 'the place of rain'.

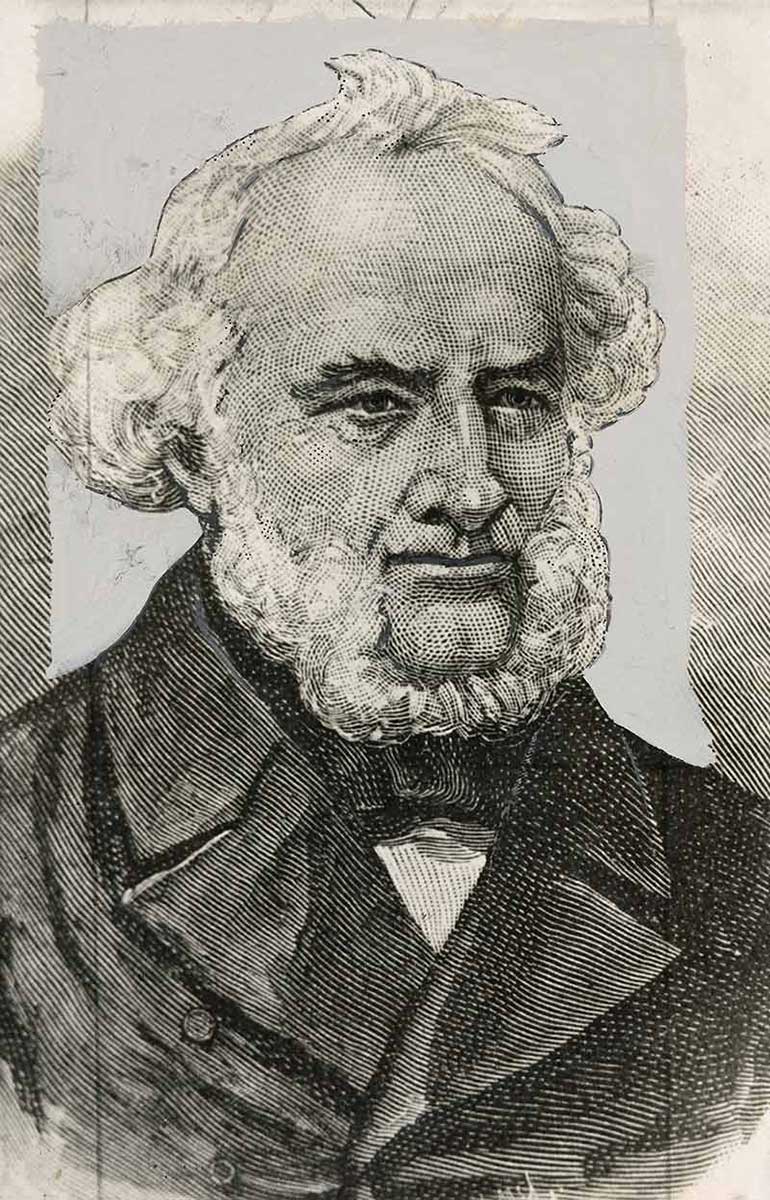

Lockyer had been sent out from Sydney by Governor Ralph Darling. A few months later he also despatched Captain James Stirling, commander of the Success, to reconnoitre the Swan River region for a settlement site.

Stirling, accompanied by Charles Fraser, colonial botanist of New South Wales, arrived at Rottnest Island on 5 March 1827.

The first exploration

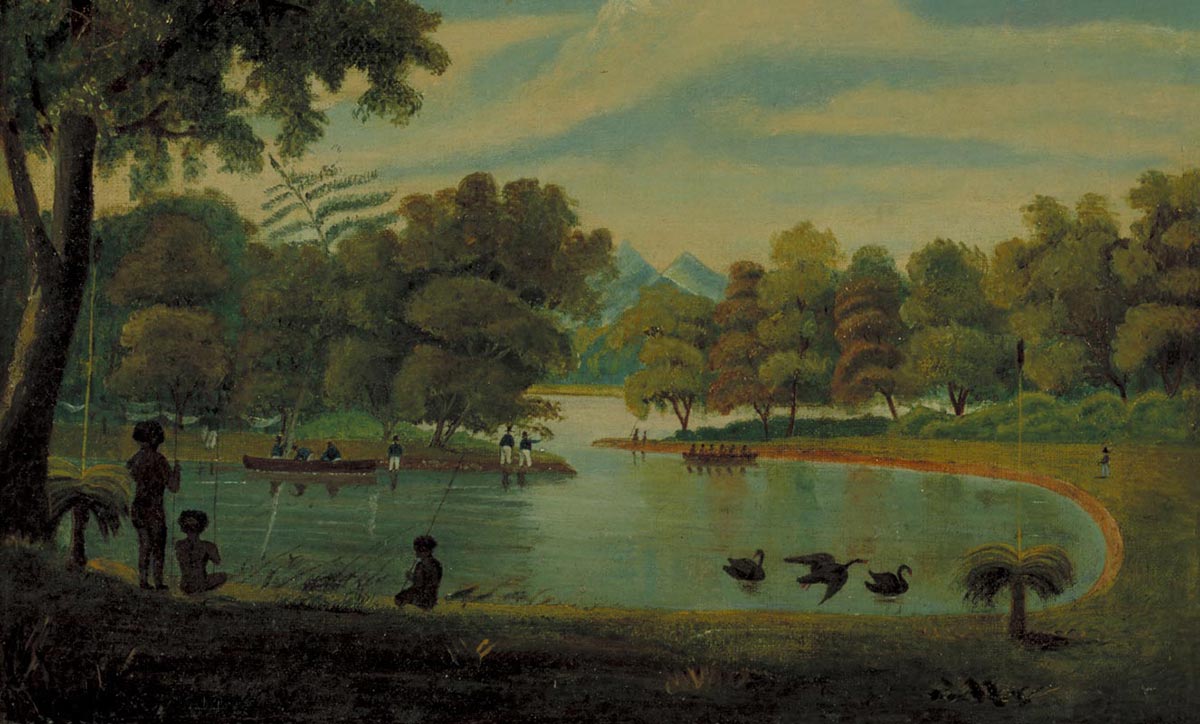

Setting out three days later, Stirling and his party navigated around 54 kilometres up the Swan River, assessing the land for its suitability for agriculture and settlement.

When Stirling returned to Sydney, he reported his findings to Governor Darling. He enthusiastically described the strategic merits of a colony at Swan River, while Fraser praised the region’s rich soil, based on his observation of the greenness of the vegetation and the height of the trees.

A colony of free settlers

Despite Stirling’s glowing report, endorsed by Darling, colonial administrators in Britain initially rejected the proposal, baulking at the expense of setting up a new colony.

Stirling, who had briefly returned to Britain and had ambitions to govern the new colony, argued that the financial burden on the government could be limited if Swan River was established as a free settlement funded by private capital.

Stirling’s efforts to convince the government were helped by enthusiastic reports in the London press (some fed by Stirling). These reports fuelled interest in the potential colony, especially among Britons eager to start new lives in Australia untainted by the stain of the convict colony of New South Wales.

Investors were also attracted to the prospect of new lands. The most prominent of these was Thomas Peel, cousin to the then Home Secretary and later Prime Minister, Robert Peel.

The government was flooded with letters from would-be emigrants and finally agreed to the establishment of a Swan River Colony on the understanding it would receive minimal public funding, which meant no convicts would be sent to provide labour.

Prospective settlers were cautioned that emigration would be at their own risk and cost, and that they would have to develop the land they were granted in order to obtain title to it.

Thomas Peel received a commitment for a grant of 500,000 acres if he successfully landed 400 settlers by 1 November 1829. In the event, Peel arrived after this date, and with fewer settlers than promised. His private colony was beset with problems and branded a failure in London. Peel’s land grant was reduced to 250,000 acres.

Founding of Perth

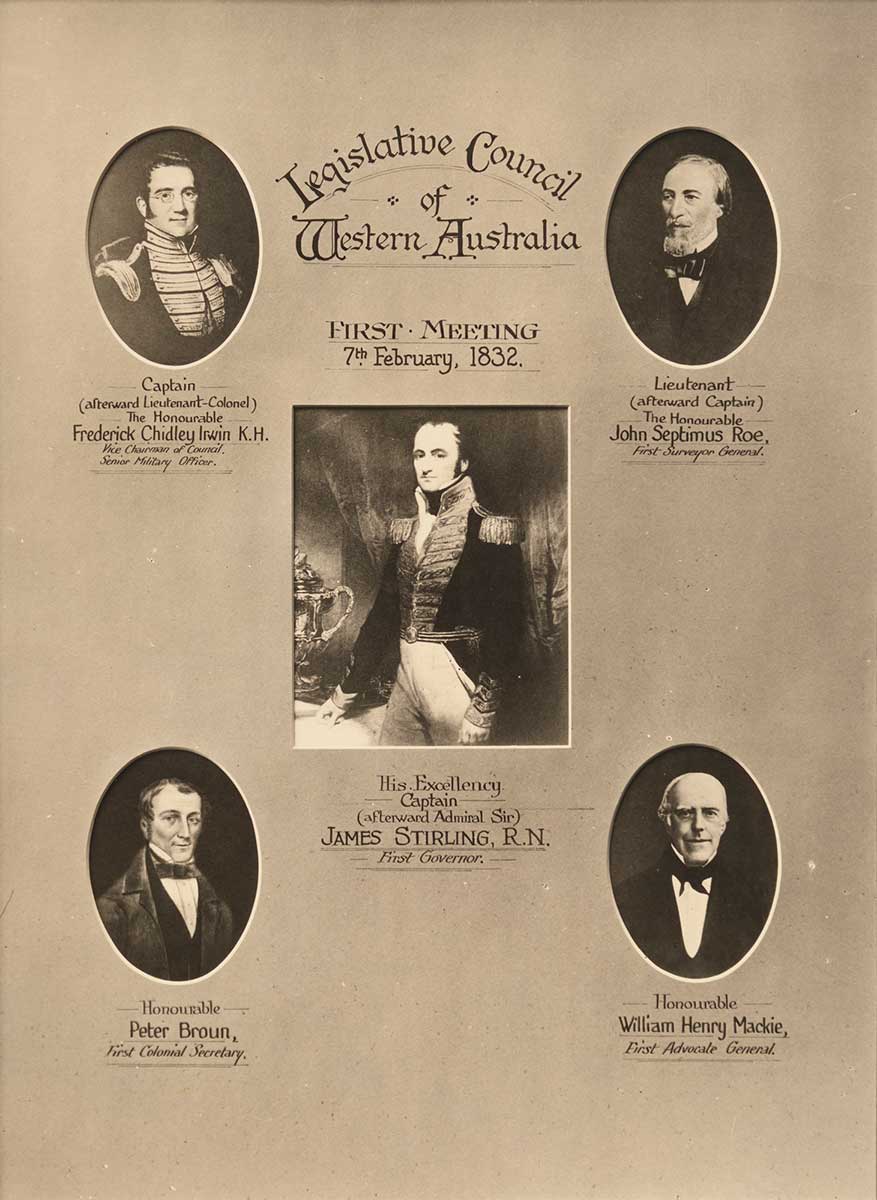

On 2 May 1829 Captain Charles Fremantle, commander of the Challenger, raised the British flag and claimed the west coast of Australia for Britain.

Shortly afterwards, the first Swan River settlers arrived on the Parmelia and the Sulphur.

The colonisation of Whadjuk country began with the reading of an official proclamation at Garden Island on 18 June, naming James Stirling as lieutenant governor.

Stirling soon realised that the soil on the coast was not suited to agriculture.

He decided to establish two towns in the new settlement: a commercial port at Fremantle and a capital – which he named Perth after the Scottish city – about 19 kilometres up the Swan River.

On 12 August 1829 a large party travelled through the bush to lay the foundation stone for Perth. Not finding any suitable stones ‘contiguous to our purpose’, Mrs Helena Dance, the only woman in the party, marked the occasion by cutting a tree with an axe.

By early September the Surveyor-General, John Roe, had laid out Perth’s roads, public spaces and building lots within the three-square-mile site reserved for the town, and the first parcels of land had been allocated to settlers.

Early struggles

Intense interest in the Swan River Colony in Britain resulted in a rush of people applying to emigrate. This created difficulties for Stirling, as 25 ships full of settlers arrived within the colony’s first six months.

Life in the colony in the early 1830s was precarious and Stirling felt some migrants were not prepared for the hardships of pioneer life.

Lieutenant-Governor Stirling to Sir George Murray, Perth, 1830:

Many of the settlers who have come should never have left a safe and tranquil state of life … I would earnestly request that for a few years the helpless and inefficient may be kept from the Settlement.

Crop failure meant that supplies had to be shipped from Sydney and Van Diemen’s Land, and there was little cash in the economy because the land grant system had encouraged settlers to bring goods with them, rather than money.

Rumours about the failure of the colony and starving settlers began to circulate, which slowed immigration.

Frontier conflict

Relations between European settlers and the Noongar people, which were amicable at first, quickly deteriorated into armed conflict.

On 15 August 1833 the Aboriginal leader Yagan – whose father had been executed by firing squad, without trial, in May – was killed by two shepherds after a bounty had been put on his head.

On 28 October 1834 many people were killed in the Battle of Pinjarra, in what Bindjareb Noongar people maintain was an ambush organised by James Stirling.

Convicts arrive

By 1838, when Stirling resigned as governor, the colony had become more self-sufficient, but it still suffered from a lack of the capital and labour needed to develop its public infrastructure. The solution was to import male convicts.

Western Australia formally became a penal settlement in May 1849. Between 1850 and 1868 around 10,000 British convicts arrived at the colony. By 1868 the total population was 17,000, with convicts outnumbering settlers, 9700 to 7300.

References

Freycinet: The Swan River, State Library of Western Australia

James Stirling, Australian Dictionary of Biography

The Constitutional Centre of Western Australia: Brief History, Government of Western Australia

Thomas Peel, Australian Dictionary of Biography

John Barrow, State of the Colony of Swan River, 1st January, 1830: Chiefly Extracted from Captain Stirling’s Report, Royal Geographical Society, 1831.

Alexandra Hasluck, James Stirling, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1963.

Pamela Statham-Drew, James Stirling: Admiral and Founding Governor of Western Australia, University of Western Australia Press, Perth, 2003.