The Salto Mortale—A Reflection on Goethe’s “Italian Journey”

Documenting a rite of passage is no small feat, but it sometimes feel like we have a responsibility to do so. And isn’t all of life one?

“Naples is a paradise; everyone lives in a state of intoxicated self-forgetfulness, myself included. I seem to be a completely different person whom I hardly recognise. Yesterday I thought to myself: Either you were mad before, or you are mad now.”

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Today at an antique store in Saugatuck, MI, I picked up The Folio Society’s beautiful edition of Goethe’s Italian Journey (picture below), a memoir of the German writer’s sojourn to Italy between 1786–1788. I sat on our back porch digging into both the book and its history on a perfect West Michigan summer evening. It’s a fascinating artifact, and it’s very much alive — after all, here I am writing about it. That’s nearly 250 year of mileage, and it’s still going strong.

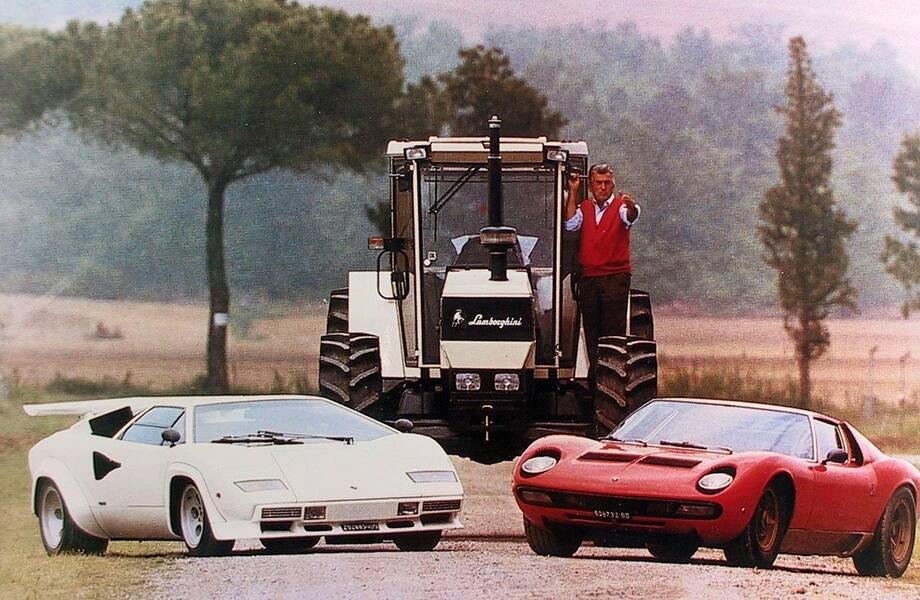

At age 37, Goethe requested a paid leave of absence from his employer, the Duke Karl August, and took a trip to Italy just as his father had done many years before. Goethe had a model of desire.

Goethe would later refer to the trip as his salto mortale — he adopted the Italian phrase to describe it — which literally means “deadly jump” — like a dare-devil leap on a motorcycle. However, in Italy it is more commonly used to refer to some risky but critical step or undertaking. For Goethe, the trip to Italy was a rite of passage. He described it as his ‘bid for freedom.’

Who hasn’t made their own bid?

While I haven’t finished the book — it’s the kind you peruse, anyway, not read cover to cover — one thing has struck me as I’ve paged through and studied its genesis: the opening and closing quotes, or epigraphs, which bookend the content. Not enough readers pay attention to these things, nor to book dedications, but both offer critical insights into the mind of a writer.

The book begins with the famous Latin saying, “Et in Arcadia ego” (used as the epigraph to open the first chapter of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, btw). Perhaps Goethe viewed Italy as a kind of paradise, but one affected by mortality. After all, the first thing he saw there was the ruins of an ancient civilization that had died.

The poet W.H. Auden would describe Italian Journey in a way that captures its importance for Goethe, but also for us readers: “Some journeys — Goethe’s was one — really are quests. Italian Journey is not only a description of places, persons and things, but also a psychological document of the first importance.” It is what happens when psychology comes into contact with real things, and a person is changed.

I think I am so attracted to this kind of book not primarily because I lived in Italy for three years (that does help me concretize it, though), but because of how incarnational good travel writing must be — much like the best sports writing, where the description of a boxer’s bloody face or the determination of Tiger Woods to prove something to his deceased father (and himself) comes out in sinewy, hard, pulsating prose that always feels grounded in the real (Woods famously tried to train with U.S. special forces — there is a physicality to the pyschology of sports, in other words).

During travel, it’s the description of places, faces, events, landscapes combined with some degree of voyeurism: a front seat to the inner life of the person who is encountering all of these new things, which are simultaneously shaping them.

In Goethe’s case, they were helping him make his salto mortale.

The beauty of a book like this is that I can take a ride in 1786, and I don’t even have to take the leap of death with Geothe if I’m not ready for it.

Italian Journey ends with the line from Ovid’s Tristia which begins “Cum repeto noctem…” (“When I remember that night….”).2 The words are from a poem written by Ovid after he was exiled from Rome by Augustus under mysterious circumstances in the year 8 A.D. Ovid looks back on his expulsion with regret (What did he do to deserve it? Scholars don’t know…). The longer he is away, the more Rome begins to take on a sacred aura, like Dante’s memory of Florence.

Perhaps that is the meaning of salto mortale that hits me the hardest tonight: there are some drives which we only get to take once. We’d better enjoy them, or at least come away transformed by them, while we’re on the road. We don’t know where the road ends.