-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Michal Grover Friedlander, “You died yesterday, I’m sorry for your loss”: After Life in Film and Opera, The Opera Quarterly, Volume 38, Issue 1-4, Winter-Autumn 2022, Pages 73–90, https://doi.org/10.1093/oq/kbae005

Close - Share Icon Share

There's not much substance to theater that doesn't occur in the space of indeterminacy between what's tangibly there, or appears to be, and whatever images of mediatized representation are there as a supplement to (the absence of) the real.

—Herbert Blau, “Virtually Yours”1

After Life

Hirokazu Kore-eda’s film After Life (1998) spans one week in a way-station between zones of death and eternity. Here the dead, rather than being judged, are each tasked with reviewing their lives and choosing a single memory that will remain with them for all eternity. The rest of their lives will be consigned to utter oblivion. Every Monday, newly deceased individuals arrive in this liminal Limbo and are given a few days to select their sole memory to be preserved. Toward the end of the week of their stay this memory will be staged and filmed. Upon arriving, these newly dead are allocated counselors—assistants who occupy this role because they have not yet been able to single out a memory of their own to be preserved—who interview them and help them to select a memory. The dead receive no guidelines to help them choose. Should they search inside themselves for a pleasurable recollection? A life-transforming memory? The helpers in the way- station, “memory workers” as Alanna Thain calls them, can help the dead refresh their memories by providing videotapes of their lives or by redirecting them if they are inclining to pick a frivolous memory as their choice. The counselors also double as set designers, producers, technicians, and camera-workers, re-creating memories as amateur low-budget short films. On Fridays the memories are reenacted, staged, and filmed. On Saturdays the dead individuals view a screening of the chosen memory, allowing a passage into eternity taking with them a filmed version of this memory as their sole possession.

In the following article I explore Kore-eda’s film’s transformation into Michel van der Aa’s opera After Life (2005–06). I am not focusing on probable reasons for choosing this film—what in the film merits (or not) a conversion into opera.2 Rather, given the transformation, I explore how the opera in relation to the film engages with its unique specificity as medium. In other words, what in the adaptation provides the opera with an opportunity to actualize itself and come into its own, in innovative ways. It is all the more intriguing given Michel van der Aa’s hypermedial style—a style which works with and through several media.3 In studying similarities, differences, and analogies between the film and the opera, in revealing moments underscored and structures shadowed, in treating traits such as temporality and the relationship between the audio and the visual—I touch on that which is unique and specific to Afterlife as an opera.

Kore-eda’s film After Life pays homage to Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)—the original Japanese title is indeed Wandafuru Raifu, “Wonderful Life,” an explicit allusion to the title of Capra’s film. It’s a Wonderful Life is a film about how a life can turn on a decisive moment, a moment that encapsulates absolutely what should be affirmed about it. In a key moment in Capra’s film, George (James Stewart), contemplating suicide, is given the possibility of “visiting” the world as it would be without him by his guardian angel, Clarence (Henry Travers). The offer bears with it the possibility of an ultimate judgment about him: whether it would have been better if George had never been born. Witnessing the fates of those he loves as they would have unfolded in his utter absence, seeing the disastrous consequences for them had his life not been lived, George becomes horrified and begs Clarence to restore his place in the world as it has been. He wants his life back just as it was, having now rediscovered his life as something he can agree with and affirm, something he now understands to be a wonderful life.

The dead in Kore-eda’s film are granted a version of this second chance. They re-traverse the space of their memories, now from a standpoint beyond life itself. There is knowledge that had not been granted the first time around, for offered here is a chance to re-do a moment from their past: the dead can revisit the past, re-creating it as they participate in it. Reality, or what has been, factually speaking, Kore-eda seems to suggest, is little more than a reference point that most of us leave behind when constructing a sense of ourselves through memory.4 In an interview, Kore-eda stated that the goal was not just to choose one memory but to see how a person’s life could be reflected through that one particular recollection.5 The affirmation of one’s life through the affirmation of a single memory brings to mind Friedrich Nietzsche’s notion of the eternal recurrence and the affirmation of a single moment:

The first question is by no means whether we are content with ourselves, but whether we are content with anything at all. If we affirm one single moment, we thus affirm not only ourselves but all existence. For nothing is self-sufficient, neither in us ourselves nor in things; and if our soul has trembled with happiness and sounded like a harp string just once, all eternity was needed to produce this one event—and in this single moment of affirmation all eternity was called good, redeemed, justified, and affirmed.6

For Nietzsche, to truly affirm one moment is to affirm the whole of life on the basis of that single moment. All things are interdependent, interconnected: “if you ever wanted one time a second time, if you ever said ‘You please me, happiness! Quick! Moment!’ then you wanted it all back!”7

Immediation

Kore-Eda began his career in documentary film, and the documentary style marks many of his films outside the genre, including After Life. Scholars have emphasized the overall documentary quality of his works along with a longstanding interest in memory’s role in the formation of identity. The documentary Without Memory (1996) concerns a man suffering from a rare condition of chronic short-term memory loss that prevents him from creating new memories. Unable, for example, to recognize his children as they grow up or even, sometimes, himself when shown films with him in them, the man was thus compelled to construct a sense of his life via the people around him. His identity was formed not through his own memories, which he could not construct, but through other people’s memories of him.8 “In all his documentaries,” writes Jonathan Ellis, “Kore-Eda looks at the role of memory in shaping a person' s life and the extent to which afterlife can be achieved through other people's reminiscences.”9 The sense of one’s memory being shaped by others is also strongly felt in After Life. Kore-eda explores film’s portrayal of memory’s complexities in its workings and the illusions involved in its restoration. In After Life we witness the process of self-conscious remembering as well as the distortions that alter memories over time. The dead perceive their memories as both real and fictive, theirs and not theirs (since these memories are re-created for them on film), as Marc Yamada explains:

After Life self-consciously thematizes the process of filmmaking, allowing the visitors to gain perspective by creating their own short films … . The guests are invited to participate in the cinematic adaptation of their memories, which helps them recognize the mediated nature of the memories that they take as real … . Instead of playing themselves in the adaptation and reexperiencing their memories from a first-person perspective, the newly deceased witness the production in the third person as codirectors while actors play their parts in the stories. Serving as the directors of their own films allow the newly deceased to relive the experiences as they provide input on set design and acting, while encouraging them to recognize the artificiality of the process of re-creating their memories.10

Ellis, for his part, likewise locates memory at the core of the director’s fundamental aesthetics of cinema: “Kore-eda seems to subscribe to the notion that cinematic images are in fact our closest artistic expression of memory.”11

Alanna Thain calls the ambiguity between the real and fiction that is rooted in documentary filmmaking “immediation”: “Afterlife investigates a cinematic state that I have termed ‘immediation’, a state of suspense between the virtual and the actual … . The virtual doubles the actual, but this doubling itself is perfectly real … . It is in this sense of the ambiguous image, embodying the doubling of the actual/virtual in the real, that I understand the intimate relation between cinema and memory in Afterlife. The force of memory in film functions as a pausing or suspension of the actual, a warping of the normal, habitual or every day, an impingement of the virtual on the actual that renders it ambiguous, and thus, generative.”12

To blend the realism of the documentary with the fiction of narrative film is to play with the perceived differences between documentary and drama. The fictional seems more real, the real more fictional. After Life demonstrates how these two modes of representation are intertwined. Yamada points to a scene toward the end of the film that reflects this state:

The nonduality between a documentary and fictional style is reflected in the collapse of the division between the stage and real world at the way station … divisions dissolve when the real world is revealed as another stage. A skylight in the roof of the dormitory, through which characters view outside conditions, exposes the conditionality of any one perspective on the world. At the very end of the film, Shiori … stops beneath the skylight on her way to interview new inductees, gazing up to catch a glimpse of a nighttime moon—a strange sight for the early morning. Suddenly, the moon disappears, leaving behind a blue sky, and we learn that the scenes of the outside world viewed through the window are merely pictures that are regularly changed by workers on the roof. What the viewer took as the real world, then, was itself just another illusion, not unlike the sets where the memories are turned into film.13

Kore-eda himself attests to the conflation of the virtual and the real, documentary and fiction, non-actors and actors: “I [Kore-eda] said to the cameraman: ‘Let's choose techniques from both fiction and documentary without distinguishing between them.’”14 Interviews about memories were conducted with hundreds of people and then incorporated into the film. People telling their memories were integrated into it, along with the testimonies of actors drawing on their own memories as well as actors working from a script.15 It is impossible to tell whether those being interviewed are performing their own selves or whether they are “real” people, and such ambiguity is central to the aesthetics of the film: “I [Kore-eda] was looking for that uncertain area between ‘objective record’ and ‘recollection,’ and it was very interesting when the boundary between ‘ordinary people’ and actors had a kind of combustion and started to break down.”16

Film’s Afterlife in Opera

In 2005–06, Michel van der Aa composed After Life, an opera based on Kore-eda’s film.17 The opera adopts the film’s premise that each of the dead must select a memory to remain with them for eternity. It follows the film’s narrative structure, as each day spent in the way-station forms a scene in the opera, though what occurs on each day is not the same as in the film. The opera is faithful to the film’s central plot, and just like in the film, a complication manifests itself: the memories of the newly deceased, the recorded memories of those who died in the past, and the memories of (the dead) counselors at the way-station are intertwined.

But there are also striking differences between the opera and the film, notably in the eternally-to-be-preserved memories themselves. First and foremost, the composer conducts his own search for potential participants, interviewing them about the most meaningful and cherished memory in each of their lives. Thus the opera utilizes interviews as does the film but in the opera this material is new, having been especially conducted for the latter project. These interviews—in the form of video clips—have been incorporated into the opera.18 The opera thus features different memories while preserving the film’s documentary quality and its atmosphere marked by the presence of “real” interviews.19

Alongside the screened interview clips, the opera also contains live interviews in song. Thus the opera forges a distinction between onstage interviews, which are sung (with both parties present), and recorded and screened spoken interviews (the interviewee addressing the camera without an interviewer being present). The individuals interviewed on screen could be perceived as either actors or “real” people, especially since they do not engage in that which singles out a performer in opera: namely, they do not sing. It is tempting to conceive of the screen as the locus of documentary material, which is then transformed into fiction in the form of singing and the stage world. But matters are more complex, since, in addition, characters cross back and forth from screen to stage and from stage to screen. Crossing over from one realm to the other is possible, but the distinction between those who sing and those who speak is always retained. The ambiguity in the film as to who is “real” and who is “acting” is transposed into an ambiguity between what occurs live onstage and offstage (that is, screened). It is reinforced by the duality established between those who sing and those who speak: on stage one sings, and when there is speaking onstage it is rendered inaudible; on screen one speaks, and one sings onscreen only as an extension of a self that sings onstage. The space for singing is the stage, where, at times, inaudible speech occurs; the space of speech is the screen, and when singing infiltrates it, such speech is always accompanied by, and pointing toward, the singing onstage. More on that critical feature below.

Further significant comparisons can be made: as I’ve mentioned, the opera retains the film’s structure based on the days of the week in which the dead process their memories up to the point when they are staged and filmed. Yet whereas the film ends with the arrival of a new cohort of the dead and the onset of another week at the way-station, the opera concludes by stopping at the end of the single week. The film does not end at the end of the week we have just seen depicted. Rather, there follows in the way-station a new week, which in principle represents the same progression we have just witnessed, only with a new group of dead people and adjustments in the counselor team. The ending is like the beginning: weeks come and go, the process recurs. I would even say that cyclicality, on the whole, is an important theme in the film. Kore-eda sets After Life within the temporal dimensions of the changing of the seasons. Orange autumn leaves cover the ground at the opening, giving way to the anticipation of springtime’s cherry blossoms, turning into winter. Typical features readily identifiable with particular seasons—collecting dry leaves; the ground covered in snow—play an important part in the narrative and in the dead sorting through their memories. It is as though a mere week encompasses a year or even an entire life (in memory). As I’ve noted, the opera does not follow the film’s cyclical narrative, ending instead, full stop, when a single week is over. The opera ends with screenings of the memory-films. There is no onset of another week when everything would begin all over again.

Intermedial

Both artists are fascinated by the possibilities opened up by the questioning of boundaries. Both rethink oppositions, particularly between the virtual and the real along the lines theorized by Philip Auslander. The live and the virtual are not ontologically distinguishable, they are mutually defined and are conceived and experienced in relation to one another.20 In an interview, van der Aa has explained how in After Life he envisioned the characters onscreen becoming live and those live becoming virtual:

the same characters appear on stage and on screen. That said, I’ve avoided a rigid divide, allowing the two media [stage and screen] to flow seamlessly into each other. I’ve extended the multi-media techniques developed in my chamber opera One, and we’re using screens that can function either as transparent glass or as a surface for projection, so that the live characters can literally move from stage to screen.21

And in another interview the composer expands upon such thinking:

I tend to think of the audiovisual material as an addition and stretching of my musical and compositional vocabulary … . It was very important for One and After Life that it is so integrated: the things that happen live on stage, in the video and in the music. In One and After Life, while I was writing the music and adapting the libretto, I was also thinking about what would happen in the projections and on stage. The shifting of weight to and from the music also influences the musical structure and the phrasing. By writing all three layers in one, I could decide, for each moment, which of these elements would be foregrounded.22

Both Kore-eda and van der Aa are known for their explorations, throughout their respective careers, of intermedial slippage, passage, and diffusion. In van der Aa’s aesthetics, audiovisual and musical material are integrated; sound, music, and image permeate one another; screen and stage flow in and out of one another; live music is integrated with prerecorded electronic sound. Jelena Novak aptly analyzes one of van der Aa’s main aesthetic preoccupations:

The search for identity in van der Aa’s oeuvre is emphasized by his questioning of the impact of new media on composition, his strategic choice of musical language and the economy of the expressive means used. In many of his compositions he emphasizes the juxtaposition of live performed sound and its recording in various ways. The piece Here … could be considered as a study for the opera One, which in turn would later become a kind of predecessor of van der Aa’s second and more complex opera After Life.23

Thus questions of identity pertaining to human existence, as well as its posthumous construction, are closely related to the treatment of media. To quote Novak again: “The oeuvre of composer Michel van der Aa is characterized by an intention to question identity, and its uniqueness, constantly showing identity’s elusiveness and the multiple perspectives from which it could be perceived.”24 van der Aa himself attests to this feature:

In the solo audiovisual opera One (2002) and the audiovisual opera After Life (2005), the singers who are on stage are also singing in the projections. They do duets with themselves. They finish each other’s sentences and movements. It’s almost an extra set or layer of musicians … . The use of a visual alter-ego in the projections and an electronic alter-ego in the soundtrack both of which I do in One is another way of stretching the personality on stage and of providing insight into the mind of the protagonist. It becomes an internal dialogue. So these are techniques to put the subject of the piece in a different light.25

In Kore-eda’s work, documentary and fiction styles fuse, seamlessly continuing each other so that mostly there are only diegetic sounds. Even when we hear music, it is played by an amateur orchestra in the way-station. Conversely, for van der Aa, film and video are part of his notion of opera, truly internal to it. The audiovisual is, as it were, an extension and continuation of music. In After Life, the opera proceeds according to the documentary aesthetics embedded in the film, blurring clear distinctions and mixing fiction and documentary, actors and non-actors, locations and studio sets. Clearly, the documentary element here is fictive, requiring a suspension of disbelief, as everyone is understood to be already dead. Perhaps, and this might be a wild interpretation on my part, the opera’s electronically induced chorus of whispers are a way for the opera to provide the dead with voices. In any opera, we are always in a mode of suspension of disbelief when it comes to singing. Here, in this opera, the introduction of speaking further emphasizes the strangeness of the singing. Opera on the whole, I would suggest, is not drawn to film in order to come closer to reality but on the contrary to preserve its estrangement from it.

What We Hear, What We See

Whereas return and recurrence feature in the overall structure of the film, when it comes to the opera, what are featured instead are musical techniques of recurrence. van der Aa explains that he employs cyclical techniques to portray a sense of re-created - memories: “In many of my pieces I recreate musical moments that have already passed … . I’ve built on these techniques in the opera which is so concerned with memory, encouraging me to mess with time in an interesting way. The past can be an alter ego that challenges the present—it’s a way to create polyphony and multiple time lines, providing cyclic structures which complement the linear narrative.”26 He also uses recurring motifs featuring key words from the libretto such as “memory” and “responsibility,” as well as orchestral interludes reappearing between scenes (that is, days in the way-station) with recurring and slightly varied music.

van der Aa not only converts the narrative into musical structures. He transposes sound from the film’s diegetic soundtrack into the sonic fabric provided by the orchestra. Turning sound from this particular film into sound in the opera is not at all an obvious technique to employ: as I’ve mentioned, there are scarcely any non-diegetic sounds in the film. Part of its documentary feel derives from the impression it gives of realistic sounds. Indeed, one of the more moving scenes in the film is construed of diegetic sounds alone. It is, as it were, an audio scene, a soundscape that Shiori (a young woman, one of the recently arrived counselors) creates in the snow, made up of her labored, agitated breathing and the crushing, slashing, kicking, stamping, and throwing of snow. It presents us with an emotional climax, for she realizes she is about to lose Takashi, the man she loves (who looks young, though he has been a counselor for fifty years). He is about to choose a memory and hence leave her behind at the way-station. Her misery, frustration, and conflicted emotions—at the same time she wants and does not want him to move on—are expressed in the sounds she elicits from the snow. And snow, as we know by this point in the film, is important, both emotionally and symbolically, in many of the lives and memories we are encountering.27

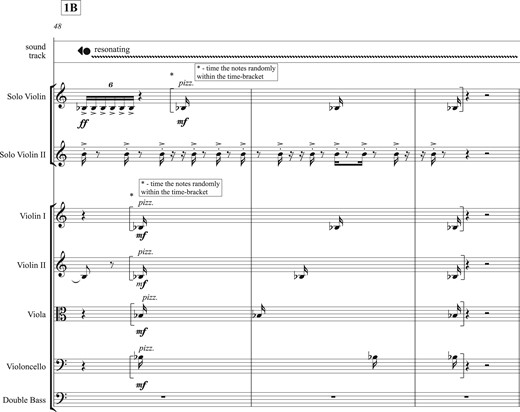

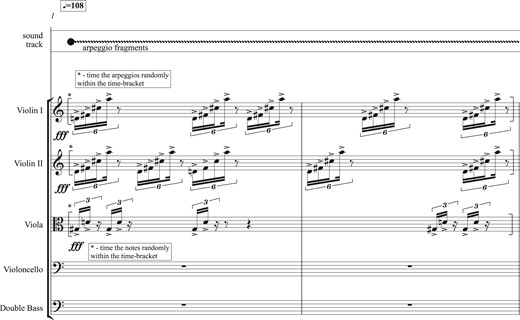

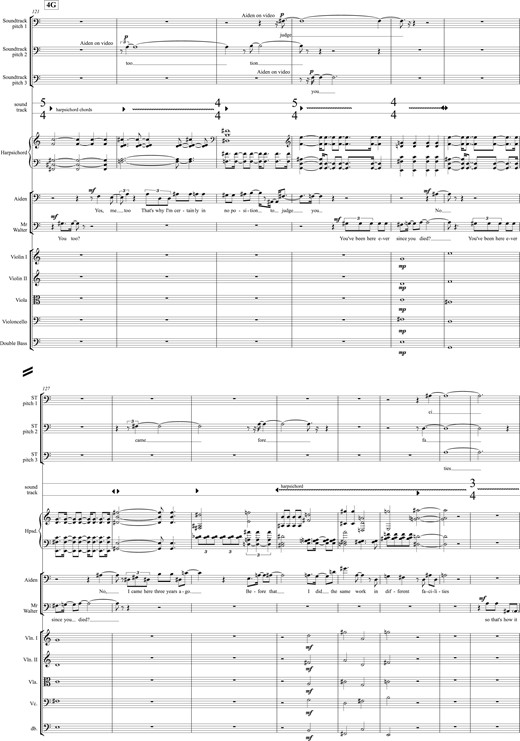

I hear in the opera, in one of the dominant orchestral themes, a reworking of the sounds of the snow from this scene. It is a prominent orchestral theme, which opens the piece, repeats, develops, and is reworked throughout in the orchestral interludes. The theme recurs at the beginning of each scene, that is, daily. It is conspicuous in its musical profile: accentuated rhythmic strokes on the strings. As the week progresses, the theme is varied and becomes more discordant and dissonant; its rhythm intensifies, and it is often joined more forcefully with electronic sounds, mutating among acoustic and electronic modes and their admixture (seeexs. 1a–1c).

After Life by Michel van der Aa and Hirokazu Kore-Eda, “Monday,” p. 4, 1B, mm. 48-50

After Life by Michel van der Aa and Hirokazu Kore-Eda, “Friday,” p. 132, mm. 1-2

After Life by Michel van der Aa and Hirokazu Kore-Eda, “Saturday,” p. 146-147, mm.15-17

At the end of the film, we do not view the filmed memories of the deceased. At the end of the opera, by contrast, we witness the dead’s filmed memories (screened rather than transformed into singing). Unlike the film, the opera shows the results of the process of remembering made into screened film clips. The medium of film won’t include the filmed memories, whereas the medium of opera, with less of a stake in visuality and the image, would show them. The memories the opera re-creates are seconds-long film clips, consisting only of visuals, no sound—except for what we hear of the rolling camera, that is, the sound of the moment of filming, not the sound of the time of the memory. In the representation of the process’s closure, the encapsulation of a life’s meaning within a single memory, the opera provides visual representation of the meaning one attributes to a life, it provides memory as film.

Unlike Film

The film, as well as the opera, presents the time the (dead) counselors spend at the way-station as itself a form of “lived” time: it, too, is a meaningful time out of which they can choose a memory. For them, the way-station is experienced within the ongoing flow of existence.28 It is as if, even though they are dead, they can keep gathering memories from their time in limbo. This peculiar situation is the basis for one of the plot’s central elements, which is also the only filmed memory shown in both the film and the opera. I will recount the memory as it appears in the opera and then draw parallels and differences with how it is presented in the film. van der Aa’s After Life projects short film clips of the dead’s selected memories, one after the other. The last to be shown is the memory chosen by the counselor Aiden. After fifty years in the way-station, he has finally decided on the memory he would like preserved, drawn from the time he has spent with the other counselors in the way-station’s limbo. Aiden chooses the moment he realized that the time he spent, as a dead person, at the way-station is in fact the most valuable time of his “life”: the memory of the crew he has worked with is what he chooses to cherish and take with him into eternity. When filming his memory, Aiden turns the camera around to film the crew as they are looking at him, followed by the projector casting a white square of light. The end of the opera is cast as the aftermath of a movie screening; it ends as if it were a film or at least could be taken to be one.

This final memory, taken from the counselor who for fifty years was unable to choose the memory to accompany him on his further journey, is also the only filmed memory that Kore-eda does portray. Takashi (the name of the counselor in the film) looks directly at the camera—seemingly at us—as though he were being interviewed. But really he is looking at what he wants to remember. We are then shown what he had been looking at—the workers on his team. They look back, realizing he has chosen them. He gazes at them gazing at him, accompanied by no sound but what can be heard from the rolling camera. Takashi has made the present, which is moreover the present with the team that usually only assists in producing the filmed moments from the lives of the dead, into his one and only memory. One could also say that this memory need not be set, directed, or produced: it is, as it were, a “documentary” moment of the filming of the real (within the film). Takashi’s memory-film ends with a black screen—as opposed to the white screen of van der Aa’s opera. But Kore-eda’s After Life does not end there. The shot that follows shows the screening hall, where we view the counselors viewing Takashi’s memory, his chair now empty. Soon we will witness the onset of a new week at the way-station.

Operatic Afterlife

There are scenes that are unique to either the film or the opera. One such scene, present only in the film, shows Shiori searching for materials required to stage the memories in a nearby city (in which the living go about their business as usual). She sees, she performs actions, but to the living she is nonexistent, invisible, seen through and ignored. Another such scene in the film, already mentioned, involves Shiori making sounds in the snow. These scenes seem to me to subtract even more from what is already a rather minimalist film (in which the dead’s lives are wholly “subtracted,” except for a single memory). Indeed, in the former scene, Shiori becomes invisible, and in the latter she is mute.

The opera adds not so much scenes but rather adds certain twists to the scenes of the film. Often they involve Aiden. In one such scene, originating in the film, Aiden is reading a book entitled One—the title of Aa’s previous opera.29 Other scenes are made “operatic” by being turned into ensembles: the station’s regulations read by a single voice in the film are sung in unison by a trio in the opera. I would argue that the most operatic, indeed original scene in the opera is a duet in which each singer also sings with his multiplied virtual self, or sings an aria with one’s multiple screened selves at the same time that another solo with its multiple selves is underway. A scene I now turn to in some detail.

I will summarize the background to the scene which is common to the film and the opera, albeit with some significant variations. It involves two counselors (Takashi/Aiden, Shiori/Sarah), as well as one of the deceased (Watanabe/Wilson) who has arrived that week in the way-station. Shiori, in love with Takashi, realizes that Watanabe’s chosen memory of his young self and his young wife (Kira) touches on Takashi’s life. Indeed, Kira had previously been Takashi’s fiancée and became engaged to Watanabe only after Takashi’s death in the war. If this were not complex enough, Shiori finds the recorded memory of Kira, who has already died and has previously passed through that same way-station. As Shiori and Takashi watch Kira’s recorded memory, they realize that it is a memory of Takashi, her fiancé who died in the war. In the film, this leads to the climactic scene, a virtuosic display of gazes, while in the opera, it is a virtuosic scene of audiovisual multiplications.

I start with an account of the scene as it appears in the film. Takashi is on the brink of choosing his memory. The turning point occurs when he and Shiori watch a video of the memory chosen by his fiancée after she died. Takashi realizes that she remembered him and chooses a moment with him to be her lasting memory. She recalls them sitting together on a bench outside. We first see the screening of her reconstructed memory, then there is a cut to Takashi and Shiori watching it. The next cut reveals the real-life event referred to by the fiancée’s memory. We then cut to Takashi and Shiori watching the video of the actual event. Next, a cut to Takashi and Shiori sitting side by side on a bench, positioned identically as in what they have just witnessed with Takashi and his fiancée Kira—as if they were mimicking the scenes they have just watched, the re-created memory and the event. This is followed by a cut to Takashi silently processing in his head what he had just watched, taking it all in while sitting on an identical-looking bench, one used to stage the dead’s memories. The posture of his body and the gestures he makes with his hands are identical to how he appears in the screenings.

The scene includes five cuts over two minutes.30 It is a vertiginous sequence of shifting gazes: Takashi watches himself as he is seen within another’s (Kira’s) memory of him; he watches himself as young man (not merely looking young as he has been for the past fifty years); he watches the young woman he had known as an old woman in someone else’s (Watanabe’s) memory. Watanabe (the man Kira ended up marrying) chose a memory with the same woman, drawn from a time when they were both old, sitting on the same bench that features in Kira’s memory with Takashi. The setting repeats, the bench recurs; in each sequence, Takashi is leaning forward, looking away, hands crossed. The woman beside him (Kira, Shiori) is looking at him, and he does not look back but feels the gaze upon him. What is underscored here are acts of viewing.

The scene in the opera in which Aiden (Takashi) realizes he is ready to make his choice is quite different. It has been created out of related material but is structured differently. To begin with, the scene is between the two men, Aiden (Takashi in the film) and Walter (Watanabe in the film). The film’s intimate scene involves the two counselors (Takashi and Shiori), and Shiori is placed in the position of Kira, the fiancée who lost her true love. In the opera, the intimate moment is between the two men, Aiden and Walter, who both love the same women. It is as though the opera, through Wilson, offers Aiden a view of what he might have become (had he lived longer); in the film, it is Shiori who is about to lose Takashi, who is identified with Kira, who lost her fiancé. In each pair, Watanabe (Wilson)/Takashi (Aiden) and Shiori (Sarah)/Kira (Kira), one partner has lived a long life while the other’s life had been taken early. Each younger half of these pairings could not (Takashi/Aiden) or would not (Shiori/Sarah) choose a memory, as though their lives still await moments that they might take with them into eternity.

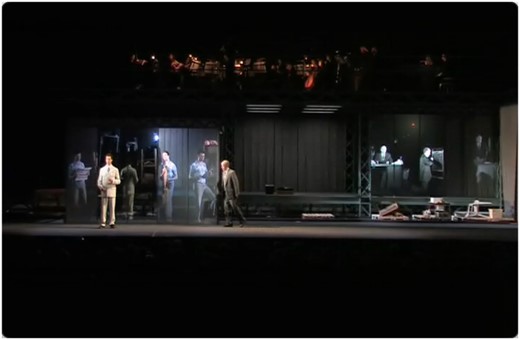

In the scene in the opera, Aiden and Wilson are onstage singing, and each has three onscreen virtual singing selves. The film’s multiplicity of gazes is converted into splintering singing selves in the opera.31 Wilson and Aiden are multiplied onscreen until, gradually, the scene has built up to five Aidens—an onstage singer, his reflection on a screen/mirror, three onscreen Aidens; together with five similarly multiplied Wilsons. The Walters and Aidens onscreen are singing simpler melodic phrases and long-held notes together with the more fluid melodic lines of the live singers. At times, the music is more evenly distributed among the onstage and virtual singers. They sing with themselves and one another in an odd duet resonating across media—comprising many selves (see figs. 1–2 and ex. 2).32

After Life by Michel van der Aa and Hirokazu Kore-Eda, “Thursday”

After Life by Michel van der Aa and Hirokazu Kore-Eda, “Thursday”

After Life by Michel van der Aa and Hirokazu Kore-Eda “Thursday,” p. 111, 4G, mm. 121-134

Aiden makes two revelations to Wilson in this transformed scene in the opera. The first is about his age. Aiden is seventy-two years old, the same age as Wilson. For the past fifty years he remained looking twenty-two, the age at which he died. The second revelation is that he and all the other counselors at the way-station have been unable to select a memory: “everyone who worked here couldn’t choose, either.” Their conversation continues with Walter asking whether Aiden couldn’t or wouldn’t choose. Perhaps, Walter continues, “not choosing might be one way to take responsibility.” At this point, all eight voices sing “responsibility” together over and over again, establishing the scene’s climax as one of doubting—rather than affirming the narrative’s premise. Not agreeing to reduce one’s life to a single memory might be the responsible stance. The scene provides an alternative to the film’s premise: refusing to choose a single memory at the expense of all the rest is another way to choose to affirm one’s entire life, all of one’s memories. This vocal moment gives way to two full-screen close-ups on Kira’s face: one showing her young, when she had been Aiden’s fiancée, and the other showing her old, when she was Walter’s wife. The screened images are positioned behind Aiden and Wilson, respectively. Kira’s facial features, seen up close, might be the opera’s single reference that its source is a Japanese film.

It is not that the film is free of self-doubts. Indeed, the conversation about taking “responsibility” originates in the film in a different context (it also appears in another scene in the opera). Yet in the film it is voiced by Iseya, dead at twenty-one, who now refuses to accept the rules of the way-station: “Who actually wants to live with a single memory forever, however perfect it happens to be? It’s your whole set-up here that needs rethinking.” He would like to take a dream with him to the afterlife, indeed, to choose something that never happened, “wonder[ing] whether he can invent an image of the future,” writes Ellis.33 When that proves to be beyond the scope of the place’s regulations, he refuses altogether to choose, precisely on the grounds that he bears a responsibility to memory and remembering—that is, to his life. It is he, in a conversation with Watanabe, who raises the concern about “responsibility.” Ultimately we see Iseya remaining as a counselor in the way-station, as the next weekly cohort of the dead arrive.

The scene analyzed above, apart from its central narrative importance, is also the one scene where one most clearly recognizes how the opera has taken up the film and has transformed it. With its multiplications of live and screened singing identities, it seems to encapsulate much of what the opera has reconceived out of the original film, portraying screen and live singing as that which is operatic. I would argue that the scene is the opera’s chosen memory—from its past, the film. In the process of remembering, the scene is refigured in the new place or medium, the memory transformed into images and voices.

To conclude I would claim that it is not the opera’s incorporation of alternative memories from those found in the film; nor the transformation of ambiguities between documentary and fiction into those between stage and screen, live and virtual; nor the film’s cyclicality transposed into music technique; nor the film’s diegetic sound reworked into the opera’s interludes; nor the opera’s filmed memories of the deceased. But rather a single scene—a duet between two characters singing live simultaneously with their multiple virtual selves, a duet/dectet—that captures the operatic take on the film.

Michal Grover Friedlander is head of the Musicology program in the Buchmann Mehta School of Music at Tel Aviv University. Her main research areas are voice, opera, music theatre in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and opera in relation to other arts (cinema, theatre, performance, dance, and staging). Her book publications include Vocal Apparitions: The Attraction of Cinema to Opera, Operatic Afterlives, and Staging Voice. Grover Friedlander is director, choreographer, and founder of TA OPERA ZUTA, an ensemble specializing in contemporary opera, music theatre, and collaborative projects. She has developed a unique approach she calls “choreography of the voice.” Grover Friedlander has directed in Israel (with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra), Italy, Germany, and Japan.

* I am grateful to Michel van der Aa and Jelena Novak for their generous sharing of materials related to the opera After Life, and for their precious observations along the way. I also thank Jelena Novak, João Pedro Cachopo, and the anonymous reader for their thoughtful comments.

Notes

Herbert Blau, “Virtually Yours: Presence, Liveness, Lessness,” in Critical Theory and Performance, ed. Janelle Reinelt and Joseph Roach (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007), 544.

For the other way around—film aspiring to the condition of opera—see Michal Grover Friedlander, Vocal Apparitions: The Attraction of Cinema to Opera (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005) and Michal Grover Friedlander, Operatic Afterlives (New York: Zone Books, 2011). On opera and adaptation, see Linda Hutcheon and Michael Hutcheon, “Adaptation and Opera,” in The Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies, ed. Thomas Leitch (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 305–23.

On hypermediality see Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 33–34. On Opera as always being hypermedial, see Tereza Havelková, Opera as Hypermedium (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

For elaboration see Jonathan Ellis, “Reviews: After Life,” Film Quarterly 57, no. 1 (Fall 2003): 36.

In Linda Ehrlich, The Films of Kore-eda Hirokazu: An Elemental Cinema (London: Palgrave, 2019), 80.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, trans. and ed. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Random House, 1967), 532–33.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Penguin, 1995), 4.19, 10: “The Drunken Song.”

See discussion of the film in, for example, Ehrlich, Films of Kore-eda Hirokazu, 77–90.

Ellis, “Reviews: After Life,” 32–33.

Marc Yamada, "Between Documentary and Fiction: The Films of Kore-Eda Hirokazu," Journal of Religion & Film 20, no. 3 (2016): 12–13.

Ellis, “Reviews: After Life,” 32–33. In fact Kore-eda does not, ultimately, portray the memories on screen. For more on this topic, see below.

Alanna Thain, “Death Every Sunday Afternoon: The Virtual Realities of Hirokazu Koreeda's After Life,” in Millennial Cinema: Memory in Global Film, ed. Amresh Sinha and Terence McSweeney (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 55–56. Keith Ansell Pearson, looking at Deleuze’s treatment of the virtual power of memory, writes that for Deleuze, the past is formed at the same time as the present. That is, for Deleuze, memory constitutes the virtual-actual circuit. The two co-exist. Keith Ansell Pearson, “The Reality of the Virtual: Bergson and Deleuze,” MLN, Dec., 2005, vol. 120, no. 5, 1112–1127.

Yamada, "Between Documentary and Fiction,” 14–15.

Linda Ehrlich and Yoshiko Kishi, “The Filmmaker as Listener: A New Look at Kore-eda,” Cinemaya 61–62 (2003–4): 43–44.

Thain, “Death Every Sunday Afternoon,” 61.

Ehrlich and Kishi, “The Filmmaker as Listener,” 44.

In 2009, Aa created a version reducing the cast from eight to six singers. Limbo, An Opera (2019), created by Ta Opera Zuta, is another opera project tied to Kore-eda’s After Life. Limbo is about ways of evaluating one’s life through remembering and memory. It is, in several ways, about the inability to remember. The meaning of life crystallizing around one meaningful memory as it is offered in the film After Life serves as one option. Two short excerpts from the film are screened, alongside an excerpt from It’s a Wonderful Life, where one views the consequences of the world without you, and from Citizen Kane, in which an object of childhood contains the secret of the unity of a life. Limbo also contains new music, flash fiction, and more. Each scene embodies an attempt to remember. (Michal Grover Friedlander/Director, Eli Friedlander/Stage design, Jelena Novak/Dramaturgical Advice. Music: Hadas Pe’ery / “Two excerpts from Hebrew lessons”; Sireen Elias / “Samai’e”; Barbara Strozzi / “Che si può fare”; New Orleans funeral march “When the Saints”; English folk song “I will give my love an apple.” Performing Artists: Doron Schleifer/countertenor; Rona Shrira/contralto; Ryo Takenoshita/performance; Taum Karni/conductor; Noam Sharet/flute; Inbar Sharet/clarinet; Neta Maimon/cello; Ziv Kaplan/percussion; Text Fragments: Omer Friedlander/Story; Ryo Takenoshita/Recollection. Studio Bank, Tel Aviv, 2019.)

Aa’s After Life merges recorded live and virtual realities, and as such differs from Thomas Ades’s The Exterminating Angel (2016) based on Buñuel’s film of the same name from 1962. For a discussion of liveness and fixity in the conversion from film to opera, see Laura Tunbridge, “Exterminating the Recording Angel,” Opera Quarterly 35, no. 1–2 (2019): 63–76; doi: 10.1093/oq/kbz011.

For Aa’s documentary dimension, see Jelena Novak, “Televisual Opera after TV,” in Das Wohnzimmer als Loge. Von der Fernsehoper zum medialen Musiktheater, Thurnauer Schriften zum Musiktheater, ed. Matthias Henke und Sara Beimdieke (Würzburg: Königshausen und Neumann, 2016), 179–96 (193).

Philip Auslander, Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, 3rd edn. (New York: Routledge, 2023).

David Allenby, “Interview about After Life,” February 2006, https://www.vanderaa.net/quarternotes-afterlife.

Jonathan W. Marshall, “Freezing the Music and Fetishising the Subject: The Audiovisual Dramaturgy of Michel van der Aa,” ed. Cat Hope and Jonathan W. Marshall (Proceedings of the 2007 Totally Huge New Music Festival Conference) Sound Scripts vol. 2 (2009): 18.

Jelena Novak, Postopera: Reinventing the Voice-Body (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 42.

Novak, Postopera, 42.

Marshall, “Freezing the Music,” 17.

Allenby, “Interview about After Life.”

Snow is a central theme in Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life. It serves, for instance, to mark the protagonist George’s thoughts of suicide, which provide the basis for the entire film. Kore-eda might be alluding to the theme in After Life in his snow scene.

Yamada, "Between Documentary and Fiction,” 15.

On uniqueness as an important theme in van der Aa’s oeuvre, see Jelena Novak, “Music beyond Human, Conversation with Michel van der Aa,” New Sound International Journal of Music 55 (2020): 7–22.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7rk1HFC60e0 [1:39:00-1:41:21].

The scenes in the film featuring Watanabe, Takashi, and Shiori leading up to Takashi’s ultimate ability to select his single memory are spread out over four days, among other memories and happenings in the way-station. The opera, in contrast, reworks and condenses these episodes into one scene.

Video of the opera is unavailable commercially. These captures are taken from a video recording made available thanks to Dutch National Opera.

Ellis, “Reviews: After Life,” 37.