Insular Celtic languages

Last updated| Insular Celtic | |

|---|---|

| (generally accepted) | |

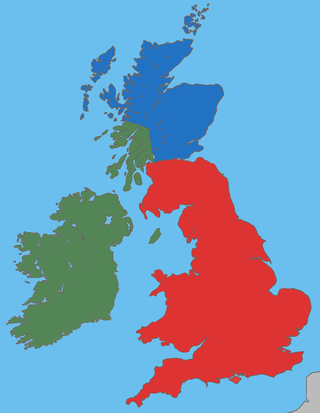

| Geographic distribution | Brittany, Cornwall, Ireland, the Isle of Man, Scotland, and Wales |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | insu1254 |

Insular Celtic languages are the group of Celtic languages spoken in Brittany, Great Britain, Ireland, and the Isle of Man. All surviving Celtic languages are in the Insular group, including Breton, which is spoken on continental Europe in Brittany, France. The Continental Celtic languages, although once widely spoken in mainland Europe and in Anatolia, [1] are extinct.

Contents

- Insular Celtic hypothesis

- Insular Celtic as a language area

- Absolute and dependent verb

- Possible pre-Celtic substratum

- Notes

- References

- Sources

Six Insular Celtic languages are extant (in all cases written and spoken) in two distinct groups:

- Insular Celtic languages

Insular Celtic hypothesis

The Insular Celtic hypothesis is the theory that these languages evolved together in those places, having a later common ancestor than any of the Continental Celtic languages such as Celtiberian, Gaulish, Galatian, and Lepontic, among others, all of which are long extinct. This linguistic division of Celtic languages into Insular and Continental contrasts with the P/Q Celtic hypothesis.

The proponents of the Insular hypothesis (such as Cowgill 1975; McCone 1991, 1992; and Schrijver 1995) point to shared innovations among these – chiefly:

- inflected prepositions

- shared use of certain verbal particles

- VSO word order

- differentiation of absolute and conjunct verb endings as found extensively in Old Irish and less so in Middle Welsh (see Morphology of the Proto-Celtic language).

The proponents assert that a strong partition between the Brittonic languages with Gaulish (P-Celtic) on one side and the Goidelic languages with Celtiberian (Q-Celtic) on the other, may be superficial, owing to a language contact phenomenon. They add the identical sound shift (/kʷ/ to /p/) could have occurred independently in the predecessors of Gaulish and Brittonic, or have spread through language contact between those two groups. Further, the Italic languages had a similar divergence between Latino-Faliscan, which kept /kʷ/, and Osco-Umbrian, which changed it to /p/. Some historians, such as George Buchanan in the 16th century, had suggested the Brythonic or P-Celtic language was a descendant of the Picts' language. Indeed, the tribe of the Pritani has Qritani (and, orthographically orthodox in modern form but counterintuitively written Cruthin) (Q-Celtic) cognate forms. [2] [lower-alpha 1]

Under the Insular hypothesis, the family tree of the insular Celtic languages is thus as follows:

| Insular Celtic | |

This table lists cognates showing the development of Proto-Celtic */kʷ/ to /p/ in Gaulish and the Brittonic languages but to /k/ in the Goidelic languages.

| Proto- Celtic | Gaulish and Brittonic languages | Goidelic languages | English Gloss | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaulish | Welsh | Cornish | Breton | Primitive Irish | Modern Irish | Scottish Gaelic | Manx | ||

| *kʷennos | pennos | pen | penn | penn | *kʷennos | ceann | ceann | kione | "head" |

| *kʷetwar- | petuar | pedwar | peswar | pevar | *kʷetwar- | ceathair | ceithir | kiare | "four" |

| *kʷenkʷe | pempe | pump a | pymp | pemp | *kʷenkʷe | cúig | còig | queig | "five" |

| *kʷeis | pis | pwy | piw | piv | *kʷeis | cé (older cia) | cò/cia | quoi | "who" |

- ^ In Welsh orthography ⟨u⟩ denotes [i] or [ɪ]

A significant difference between Goidelic and Brittonic languages is the transformation of *an, *am to a denasalised vowel with lengthening, é, before an originally voiceless stop or fricative, cf. Old Irish éc "death", écath "fish hook", dét "tooth", cét "hundred" vs. Welsh angau, angad, dant, and cant. Otherwise:

- the nasal is retained before a vowel, i̯, w, m, and a liquid:

- Old Irish : ben "woman" (< *benā)

- Old Irish: gainethar "he/she is born" (< *gan-i̯e-tor)

- Old Irish: ainb "ignorant" (< *anwiss)

- the nasal passes to en before another n:

- Old Irish: benn "peak" (< *banno) (vs. Welsh bann)

- Middle Irish : ro-geinn "finds a place" (< *ganne) (vs. Welsh gannaf)

- the nasal passes to in, im before a voiced stop

- Old Irish: imb "butter" (vs. Breton aman(en)n, Cornish amanyn)

- Old Irish: ingen "nail" (vs. Old Welsh eguin)

- Old Irish: tengae "tongue" (vs. Welsh tafod)

- ing "strait" (vs. Middle Welsh eh-ang "wide")

Insular Celtic as a language area

In order to show that shared innovations are from a common descent it is necessary that they do not arise because of language contact after initial separation. A language area can result from widespread bilingualism, perhaps because of exogamy, and absence of sharp sociolinguistic division.

Ranko Matasović has provided a list of changes which affected both branches of Insular Celtic but for which there is no evidence that they should be dated to a putative Proto-Insular Celtic period. [3] These are:

- Phonological Changes

- The lenition of voiceless stops

- Raising/i-affection

- Lowering/a-affection

- Apocope

- Syncope

- Morphological Changes

- Creation of conjugated prepositions

- Loss of case inflection of personal pronouns (historical case-inflected forms)

- Creation of the equative degree

- Creation of the imperfect

- Creation of the conditional mood

- Morphosyntactic and Syntactic

- Rigidisation of VSO order

- Creation of preposed definite articles

- Creation of particles expressing sentence affirmation and negation

- Creation of periphrastic construction

- Creation of object markers

- Use of ordinal numbers in the sense of "one of".

Absolute and dependent verb

The Insular Celtic verb shows a peculiar feature unknown in any other attested Indo-European language: verbs have different conjugational forms depending on whether they appear in absolute initial position in the sentence (Insular Celtic having verb–subject–object or VSO word order) or whether they are preceded by a preverbal particle. The situation is most robustly attested in Old Irish, but it has remained to some extent in Scottish Gaelic and traces of it are present in Middle Welsh as well.

Forms that appear in sentence-initial position are called absolute, those that appear after a particle are called conjunct (see Dependent and independent verb forms for details). The paradigm of the present active indicative of the Old Irish verb beirid "carry" is as follows; the conjunct forms are illustrated with the particle ní "not".

| Absolute | Conjunct | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Irish | English Gloss | Old Irish | English Gloss | ||

| singular | 1st person | biru | I carry | ní biur | I do not carry |

| 2nd person | biri | you carry | ní bir | you do not carry | |

| 3rd person | beirid | s/he carries | ní beir | s/he does not carry | |

| plural | 1st person | bermai | we carry | ní beram | we do not carry |

| 2nd person | beirthe | you carry | ní beirid | you do not carry | |

| 3rd person | berait | they carry | ní berat | they do not carry | |

In Scottish Gaelic this distinction is still found in certain verb-forms across almost all verbs (except for a very few). This is a VSO language. The example given in the first column below is the independent or absolute form, which must be used when the verb is in clause-initial position (or preceded in the clause by certain preverbal particles). Then following it is the dependent or conjunct form which is required when the verb is preceded in the clause by certain other preverbal particles, in particular interrogative or negative preverbal particles. In these examples, in the first column we have a verb in clause-initial position. In the second column a negative particle immediately precedes the verb, which makes the verb use the verb form or verb forms of the dependent conjugation.

| Absolute/Independent | Conjunct/Dependent |

|---|---|

| cuiridh mi "I put/will put" | cha chuir mi "I don't put/will not put" |

| òlaidh e "he drinks/will drink" | chan òl e "he doesn't drink/will not drink" |

| ceannaichidh iad "they buy/will buy" | cha cheannaich iad "they don't buy/will not buy" |

The verb forms in the above examples happen to be the same with any subject personal pronouns, not just with the particular persons chosen in the example. Also, the combination of tense–aspect–mood properties inherent in these verb forms is non-past but otherwise indefinite with respect to time, being compatible with a variety of non-past times, and context indicates the time. The sense can be completely tenseless, for example when asserting that something is always true or always happens. This verb form has erroneously been termed 'future' in many pedagogical grammars. A correct, neutral term 'INDEF1' has been used in linguistics texts.

In Middle Welsh, the distinction is seen most clearly in proverbs following the formula "X happens, Y does not happen" (Evans 1964: 119):

- Pereid y rycheu, ny phara a'e goreu "The furrows last, he who made them lasts not"

- Trenghit golut, ny threingk molut "Wealth perishes, fame perishes not"

- Tyuit maban, ny thyf y gadachan "An infant grows, his swaddling-clothes grow not"

- Chwaryit mab noeth, ny chware mab newynawc "A naked boy plays, a hungry boy plays not"

The older analysis of the distinction, as reported by Thurneysen (1946, 360 ff.), held that the absolute endings derive from Proto-Indo-European "primary endings" (used in present and future tenses) while the conjunct endings derive from the "secondary endings" (used in past tenses). Thus Old Irish absolute beirid "s/he carries" was thought to be from *bʰereti (compare Sanskrit bharati "s/he carries"), while conjunct beir was thought to be from *bʰeret (compare Sanskrit a-bharat "s/he was carrying").

Today, however, most Celticists agree that Cowgill (1975), following an idea present already in Pedersen (1913, 340 ff.), found the correct solution to the origin of the absolute/conjunct distinction: an enclitic particle, reconstructed as *es after consonants and *s after vowels, came in second position in the sentence. If the first word in the sentence was another particle, *(e)s came after that and thus before the verb, but if the verb was the first word in the sentence, *(e)s was cliticized to it. Under this theory, then, Old Irish absolute beirid comes from Proto-Celtic *bereti-s, while conjunct ní beir comes from *nī-s bereti.

The identity of the *(e)s particle remains uncertain. Cowgill suggests it might be a semantically degraded form of *esti "is", while Schrijver (1994) has argued it is derived from the particle *eti "and then", which is attested in Gaulish. Schrijver's argument is supported and expanded by Schumacher (2004), who points towards further evidence, viz., typological parallels in non-Celtic languages, and especially a large number of verb forms in all Brythonic languages that contain a particle -d (from an older *-t).

Continental Celtic languages cannot be shown to have any absolute/conjunct distinction. However, they seem to show only SVO and SOV word orders, as in other Indo-European languages. The absolute/conjunct distinction may thus be an artifact of the VSO word order that arose in Insular Celtic.

Possible pre-Celtic substratum

Insular Celtic, unlike Continental Celtic, shares some structural characteristics with various Afro-Asiatic languages which are rare in other Indo-European languages. These similarities include verb–subject–object word order, singular verbs with plural post-verbal subjects, a genitive construction similar to construct state, prepositions with fused inflected pronouns ("conjugated prepositions" or "prepositional pronouns"), and oblique relatives with pronoun copies. Such resemblances were noted as early as 1621 with regard to Welsh and the Hebrew language. [4] [5]

The hypothesis that the Insular Celtic languages had features from an Afro-Asiatic substratum (Iberian and Berber languages) was first proposed by John Morris-Jones in 1899. [6] The theory has been supported by several linguists since: Henry Jenner (1904); [7] Julius Pokorny (1927); [8] Heinrich Wagner (1959); [9] Orin Gensler (1993); [10] Theo Vennemann (1995); [11] and Ariel Shisha-Halevy (2003). [12]

Others have suggested that rather than the Afro-Asiatic influencing Insular Celtic directly, both groups of languages were influenced by a now lost substrate. This was suggested by Jongeling (2000). [13] Ranko Matasović (2012) likewise argued that the "Insular Celtic languages were subject to strong influences from an unknown, presumably non-Indo-European substratum" and found the syntactic parallelisms between Insular Celtic and Afro-Asiatic languages to be "probably not accidental". He argued that their similarities arose from "a large linguistic macro-area, encompassing parts of NW Africa, as well as large parts of Western Europe, before the arrival of the speakers of Indo-European, including Celtic". [14]

The Afro-Asiatic substrate theory, according to Raymond Hickey, "has never found much favour with scholars of the Celtic languages". [15] The theory was criticised by Kim McCone in 2006, [16] Graham Isaac in 2007, [17] and Steve Hewitt in 2009. [18] Isaac argues that the 20 points identified by Gensler are trivial, dependencies, or vacuous. Thus, he considers the theory to be not just unproven but also wrong. Instead, the similarities between Insular Celtic and Afro-Asiatic could have evolved independently.

Notes

- ↑ All other research into Pictish has been described as a postscript to Buchanan's work. This view may be something of an oversimplification: Forsyth 1997 offers a short account of the debate; Cowan & McDonald 2000 may be helpful for a broader view.

Related Research Articles

The Brittoniclanguages form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic language family; the other is Goidelic. It comprises the extant languages Breton, Cornish, and Welsh. The name Brythonic was derived by Welsh Celticist John Rhys from the Welsh word Brython, meaning Ancient Britons as opposed to an Anglo-Saxon or Gael.

The Celtic languages are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707, following Paul-Yves Pezron, who made the explicit link between the Celts described by classical writers and the Welsh and Breton languages.

Pictish is an extinct Brittonic Celtic language spoken by the Picts, the people of eastern and northern Scotland from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Virtually no direct attestations of Pictish remain, short of a limited number of geographical and personal names found on monuments and early medieval records in the area controlled by the kingdoms of the Picts. Such evidence, however, shows the language to be an Insular Celtic language related to the Brittonic language then spoken in most of the rest of Britain.

The morphology of Irish is in some respects typical of an Indo-European language. Nouns are declined for number and case, and verbs for person and number. Nouns are classified by masculine or feminine gender. Other aspects of Irish morphology, while typical for an Insular Celtic language, are not typical for Indo-European, such as the presence of inflected prepositions and the initial consonant mutations. Irish syntax is also rather different from that of most Indo-European languages, due to its use of the verb–subject–object word order.

Celtiberian or Northeastern Hispano-Celtic is an extinct Indo-European language of the Celtic branch spoken by the Celtiberians in an area of the Iberian Peninsula between the headwaters of the Douro, Tagus, Júcar and Turia rivers and the Ebro river. This language is directly attested in nearly 200 inscriptions dated from the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD, mainly in Celtiberian script, a direct adaptation of the northeastern Iberian script, but also in the Latin alphabet. The longest extant Celtiberian inscriptions are those on three Botorrita plaques, bronze plaques from Botorrita near Zaragoza, dating to the early 1st century BC, labeled Botorrita I, III and IV.

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the hypothetical ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly reconstructed through the comparative method. Proto-Celtic is generally thought to have been spoken between 1300 and 800 BC, after which it began to split into different languages. Proto-Celtic is often associated with the Urnfield culture and particularly with the Hallstatt culture. Celtic languages share common features with Italic languages that are not found in other branches of Indo-European, suggesting the possibility of an earlier Italo-Celtic linguistic unity.

The Continental Celtic languages are the now-extinct group of the Celtic languages that were spoken on the continent of Europe and in central Anatolia, as distinguished from the Insular Celtic languages of the British Isles and Brittany. Continental Celtic is a geographic, rather than linguistic, grouping of the ancient Celtic languages.

Middle Irish, also called Middle Gaelic, is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from c. 900–1200 AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old English and early Middle English. The modern Goidelic languages—Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Manx—are all descendants of Middle Irish.

The Atlantic languages of Semitic or "Semitidic" (para-Semitic) origin are a disputed concept in historical linguistics put forward by Theo Vennemann. He proposed that Semitic-language-speakers occupied regions in Europe thousands of years ago and influenced the later European languages that are not part of the Semitic family. The theory has found no notable acceptance among linguists or other relevant scholars and is criticised as being based on sparse and often-misinterpreted data.

Peter Schrijver is a Dutch linguist. He is a professor of Celtic languages at Utrecht University and a researcher of ancient Indo-European linguistics. He worked previously at Leiden University and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Celtic toponymy is the study of place names wholly or partially of Celtic origin. These names are found throughout continental Europe, Britain, Ireland, Anatolia and, latterly, through various other parts of the globe not originally occupied by Celts.

In the Goidelic languages, dependent and independent verb forms are distinct verb forms; each tense of each verb exists in both forms. Verbs are often preceded by a particle which marks negation, or a question, or has some other force. The dependent verb forms are used after a particle, while independent forms are used when the verb is not subject to a particle. For example, in Irish, the past tense of the verb feic has two forms: the independent form chonaic and the dependent form faca. The independent form is used when no particle precedes the verb, as in Chonaic mé Seán. The dependent form is used when a particle such as ní ("not") precedes the verb, as in Ní fhaca mé Seán.

The Gallo-Brittonic languages, also known as the P-Celtic languages, are a subdivision of the Celtic languages of Ancient Gaul and Celtic Britain, which share certain features. Besides common linguistic innovations, speakers of these languages shared cultural features and history. The cultural aspects are commonality of art styles and worship of similar gods. Coinage just prior to the British Roman period was also similar. In Julius Caesar's time, the Atrebates held land on both sides of the English Channel.

The Goidelic substrate hypothesis refers to the hypothesized language or languages spoken in Ireland before the arrival of the Goidelic languages.

The Insular Celts were speakers of the Insular Celtic languages in the British Isles and Brittany. The term is mostly used for the Celtic peoples of the isles up until the early Middle Ages, covering the British–Irish Iron Age, Roman Britain and Sub-Roman Britain. They included the Celtic Britons, the Picts, and the Gaels.

Common Brittonic, also known as British, Common Brythonic, or Proto-Brittonic, was a Celtic language spoken in Britain and Brittany.

In Afro-Asiatic languages, the first noun in a genitive phrase of a possessed noun followed by a possessor noun often takes on a special morphological form, which is termed the construct state. For example, in Arabic and Hebrew, the word for "queen" standing alone is malika ملكة and malkaמלכה respectively, but when the word is possessed, as in the phrase "Queen of Sheba", it becomes malikat sabaʾ ملكة سبأ and malkat šəvaמלכת שבא respectively, in which malikat and malkat are the construct state (possessed) form and malikah and malka are the absolute (unpossessed) form. In Geʽez, the word for "queen" is ንግሥት nəgəśt, but in the construct state it is ንግሥተ, as in the phrase "[the] Queen of Sheba" ንግሥታ ሣባ nəgəśta śābā..

Gaulish is an extinct Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul. In a wider sense, it also comprises varieties of Celtic that were spoken across much of central Europe ("Noric"), parts of the Balkans, and Anatolia ("Galatian"), which are thought to have been closely related. The more divergent Lepontic of Northern Italy has also sometimes been subsumed under Gaulish.

This article describes the grammar of the Old Irish language. The grammar of the language has been described with exhaustive detail by various authors, including Thurneysen, Binchy and Bergin, McCone, O'Connell, Stifter, among many others.

Neo-Brittonic, also known as Neo-Brythonic, is a stage of the Insular Celtic Brittonic languages that emerged by the middle of the sixth century CE. Neo-Brittonic languages include Old, Middle and Modern Welsh, Cornish, and Breton, as well as Cumbric.

References

- ↑ Eska, Joseph F. (2006). "Galatian language". In John T. Koch (ed.). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. Vol. III: G—L. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- ↑ "The language of the Picts". ORKNEYJAR. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023.

- ↑ Insular Celtic as a Language Area in The Celtic Languages in Contact, Hildegard Tristram, 2007.

- ↑ Steve Hewitt, "The Question of a Hamito-Semitic Substratum in Insular Celtic and Celtic from the West", Chapter 14 in John T. Koch, Barry Cunliffe, Celtic from the West3

- ↑ John Davies, Antiquae linguae Britannicae rudimenta, 1621

- ↑ J. Morris Jones, "Pre-Aryan Syntax in Insular Celtic", Appendix B of John Rhys, David Brynmor Jones, The Welsh People, 1900

- ↑ Henry Jenner, Handbook of the Cornish Language, London 1904 full text

- ↑ Das nicht-indogermanische Substrat im Irischen in Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 16, 17 and 18

- ↑ Gaeilge theilinn (1959) and subsequent articles

- ↑ "A Typological Evaluation of Celtic/Hamito-Semitic Syntactic Parallels", Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1993 https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8p00g5sd

- ↑ Theo Vennemann, "Etymologische Beziehungen im Alten Europa". Der GinkgoBaum: Germanistisches Jahrbuch für Nordeuropa 13. 39-115, 1995

- ↑ "Celtic Syntax, Egyptian-Coptic Syntax Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine ", in: Das Alte Ägypten und seine Nachbarn: Festschrift Helmut Satzinger, Krems: Österreichisches Literaturforum, 245-302

- ↑ Hewitt, Steve (2009). "The Question of a Hamito-Semitic Substratum in Insular Celtic". Language and Linguistics Compass. 3 (4): 972–995. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2009.00141.x.

- ↑ Ranko Matasović (2012). The substratum in Insular Celtic. Journal of Language Relationship • Вопросы языкового родства • 8 (2012) • Pp. 153—168.

- ↑ Raymond Hickey (24 April 2013). The Handbook of Language Contact. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 535–. ISBN 978-1-118-44869-4.

- ↑ Kim McCone, The origins and development of the Insular Celtic verbal complex, Maynooth studies in Celtic linguistics 6, 2006, ISBN 0901519464. Department of Old Irish, National University of Ireland, 2006.

- ↑ "Celtic and Afro-Asiatic" in The Celtic Languages in Contact, Papers from the Workshop within the Framework of the XIII International Congress of Celtic Studies, Bonn, 26–27 July 2007, p. 25-80 full text

- ↑ Hewitt, Steve (2009). "The Question of a Hamito-Semitic Substratum in Insular Celtic". Language and Linguistics Compass. 3 (4): 972–995. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2009.00141.x.

Sources

- Cowgill, Warren (1975). "The origins of the Insular Celtic conjunct and absolute verbal endings". In H. Rix (ed.). Flexion und Wortbildung: Akten der V. Fachtagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, Regensburg, 9.–14. September 1973. Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 40–70. ISBN 3-920153-40-5.

- Cowan, Edward J.; McDonald, R Andrew (2000). Alba : Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 9781862321519. OCLC 906858507.

- Forsyth, Katherine (1997). Language in Pictland : the case against 'non-Indo-European Pictish'. Studia Hameliana, 2. Utrecht: De Keltische Draak. ISBN 9789080278554. OCLC 906776861.

- McCone, Kim (1991). "The PIE stops and syllabic nasals in Celtic". Studia Celtica Japonica. 4: 37–69.

- McCone, Kim (1992). "Relative Chronologie: Keltisch". In R. Beekes; A. Lubotsky; J. Weitenberg (eds.). Rekonstruktion und relative Chronologie: Akten Der VIII. Fachtagung Der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, Leiden, 31. August–4. September 1987. Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 12–39. ISBN 3-85124-613-6.

- Schrijver, Peter (1995). Studies in British Celtic historical phonology. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 90-5183-820-4.

- Schumacher, Stefan (2004). Die keltischen Primärverben. Ein vergleichendes, etymologisches und morphologisches Lexikon. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 97–114. ISBN 3-85124-692-6.

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.