Harriet Ponsonby, Countess Bessborough (1761-1821), is perhaps best-known today for being the younger sister of the celebrated Duchess of Devonshire, Georgiana Cavendish (1757-1806). Although not as famous as her sister, Bessborough was a fascinating woman in her own right. As the youngest child of the 1st Earl Spencer, she grew up in a Whig party stronghold and was consequently an astute politician in adulthood, remaining, of course, eternally loyal to the Whig party. In 1780, she married Frederick Ponsonby, Viscount Duncannon, later 3rd Earl of Bessborough (1758-1844). They had four children, including the novelist and Lord Byron’s most infamous lover, Lady Caroline Lamb (1785-1828). The Bessboroughs’ marriage was quite rocky in the first couple of decades: both were avid gamblers which led to staggering debts and explosive arguments. In the 1780s, Lady Bessborough had a string of extramarital affairs, including with the Whig politician and playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Her most enduring relationship, however, was with Lord Granville Leveson Gower (1773-1846), whom she met in Naples in 1794. Their affair lasted for almost fifteen years and produced two illegitimate children; it only ended when Leveson Gower married Lady Harriet Cavendish, Lady Bessborough’s niece, in December 1809.

In 2019, I was trawling through Lady Bessborough’s correspondence with Leveson Gower when I came across a letter that immediately caught my attention due to the ominous air of its opening line: ‘My own Granville, I doubt whether I am right in what I am going to tell you’.[1] What followed was an account of a sexual assault that Lady Bessborough had experienced only a few days earlier at the hands of a man who was a member of both her social and familial networks. Real-life contemporary accounts of sexual harassment or assault told in epistolary form are quite rare. While there are several examples of letters that describe fictional sexual assaults and rapes in contemporary novels, the real-world accounts that historians have focused on tend to be those that have survived predominantly as court records and publications relating to trials.[2] Consequently, victims’ accounts tend to follow certain structures, and accounts of rape, both attempted and actualised, appear far more often than less violent assaults, which is what happened in this case. Moreover, aristocratic women seldom feature as plaintiffs in rape litigation cases, and therefore we know very little about their negative sexual experiences. Yet, Sophie Coulombeau’s recent blog on the harassment that courtier, Mary Hamilton, suffered at the hands of the Prince of Wales in the 1770s suggests that evidence of these experiences might still exist undiscovered in manuscript collections.[3] Lady Bessborough’s letter is therefore quite an extraordinary source, which I hope justifies my bringing it into the open after nearly 220 years of careful concealment.

In her letter, Lady Bessborough comprehensively described the prelude to the assault, the assault itself, and the aftermath, expressing in detail the progress of her emotions at each stage. When the assault took place, Leveson Gower had been out of the country on diplomatic service for several months. In his absence, Lady Bessborough had grown close to the man in question, and viewed him as a friend and confidante with whom she could share the anguish she felt due to her separation from her lover. She expressed her discomfort, however, about the increasing familiarity with which this man treated her. In the week before he assaulted her, she noted that his manner towards her was ‘strange’, and he made odd remarks that puzzled her. Her feelings of unease escalated when he touched her inappropriately when comforting her on an occasion when she was crying. And yet, even after this unsolicited physical contact, Lady Bessborough was still filled with self-doubt and expressed feelings of guilt for suspecting her friend of anything sinister. She was convinced she must be imagining things, which I think is sadly all too relatable for women today, when they try to assess whether a man is being inappropriate or if they are misinterpreting behaviour that is only meant in a friendly way.

I am in the process of preparing a longer publication in which I analyse how Lady Bessborough conceptualised her own culpability in the assault; she was subjected to harassment from several men while Leveson Gower was away, and she suggested that their affair had tarnished her reputation and therefore had left her vulnerable to unwanted male attention. Moreover, I examine the insights this case study can give us into the role the body played in elite gender relations. In the late Georgian period, male-female social interactions were guided by polite codes of conduct, which, the letter indicates, encompassed emotion, body language, and touch. The article will elucidate the boundaries of interpersonal conduct from a woman’s perspective, and, in doing so, it will draw together the histories of the body and sexuality with early-nineteenth century elite social mores.

Natalie Hanley-Smith is a Women’s History Network Early Career Fellow, 2021-22. She completed her doctoral thesis on 18th and 19th-century marital non-conformity at the University of Warwick in 2020. Her research interests include emotion, political culture, sexuality, and sociability. She is currently co-editing a special issue of Parliamentary History with Professor Sarah Richardson on the theme of ‘Passion, Politics and Parliament’, which is forthcoming in 2023. She is also working on a monograph, tentatively titled: Controversial intimacies: Marriage, Gossip, and Scandal in British Society, 1780-1840.

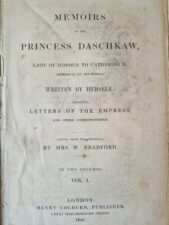

Image credit: Henrietta Ponsonby, Countess of Bessborough, by Angelica Kauffman (1793) from wikicommons.

[1] British Library, Add MS 89382/2/23, folios 16-20: Countess Bessborough to Granville Leveson Gower, 20 January 1805.

[2] For examples, see: Esther Snell, ‘Trials in Print: Narratives of Rape Trials in the Proceedings of the Old Bailey’, in David Lemmings (ed.), Crime, Courtrooms and the Public Sphere in Britain, 1700-1850 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), pp. 23-41; Garthine Walker, ‘Rereading rape and sexual violence in early modern England’, Gender & History, 10: 1 (1998), 1-25.

[3] Sophie Coulombeau, ‘This is not a love story: Mary Hamilton and George IV’. Unlocking the Mary Hamilton Papers, March 3 2021, <https://www.projects.alc.manchester.ac.uk/maryhamiltonpapers/this-is-not-a-love-story-mary-hamilton-and-george-iv/>.