Paulding County papers tell slaves’ story

Editor’s note: This is one of a series of articles written to commemorate Paulding County’s 200 anniversary. This article is one of a two-article series on freed/escaped slaves who came to Paulding County.

KIM SUTTON/for the Van Wert independent

PAULDING — “History is just waiting to be discovered” was a saying the late Les Weidenhamer often used during his 22 years as president of the John Paulding Historical Society. Recently, the adage proved to be true when a discovery was made at the society’s museum.

In a manila envelope were many scrap pieces of paper with penciled writing. This envelope had been in the George Phillips room display since the museum opened in 1984. Untouched. Unread. Waiting to be discovered.

While cleaning the room, the envelope was found and brought to the front office to decide if it should be kept. Upon closer examination — with a magnifying glass and several people taking a shot at deciphering the writing — these scrap pieces of paper were discovered to be the narrative of Loyd Phillips, a former slave and father of George Phillips.

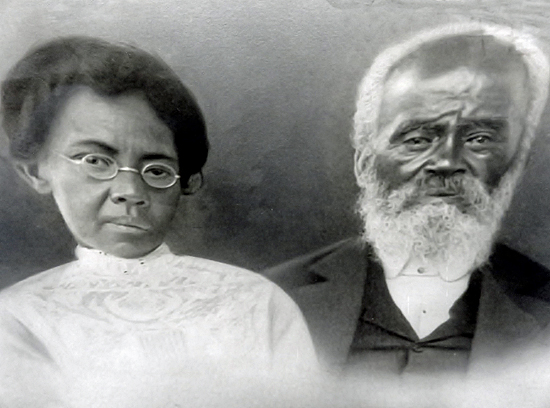

As luck would have it, or perhaps by divine intervention, Sandra Phillips, a great-great-granddaughter of Abraham Phillips, Loyd’s father, happened to visit the museum and these pieces of paper were shared with her. She volunteered to help decipher the nearly illegible writings. Although she lives north of Detroit, Sandra drove to Paulding over many weeks to carry out this important project. And so the story of Abraham and his son Loyd has come to light and brings new awareness of the role Paulding County played in the lives of freed and/or escaped slaves 160 years ago.

The following story is taken in part from George A. Phillips’ notes dated July 18, 1966, combined with the newfound notes transcribed by Sandra Phillips.

Abraham and Eliza Jane [Phillips] were slaves on separate plantations in Kentucky. They married but were required to live apart. Their owners, however, gave them the freedom to commune and visit each other. They had a son named Loyd.

Abraham had a kind master surnamed Phillips who set him free before the outbreak of the Civil War. He, along with other members of his master’s plantation, were given their freedom with some cash and property.

But Abraham could not bear to leave his beloved wife in slavery, so he borrowed $450 from a female slave on the plantation. Her name was Nancy but they called her Nellie. She was single and reluctant to go to a new country alone. She was willing, however, to loan Abraham the money to purchase the freedom of his wife, who was the property of a slave holder on an adjoining plantation. His wife could then accompany her husband in freedom to a homestead that had been given him with his freedom by his master.

In order to repay Nellie for her generosity, Abraham gave her the privilege of making her home with them for life or until he was financially able to repay her if she so desired. Nellie accepted the proposition of making her home with them for life as satisfactory payment for the loan, and the three took up their residence on the homestead farm of 40 acres of land in Washington Township, Paulding County.

Following is their son, Loyd’s, narrative:

“My name is Loyd and I was born a slave on the plantation owned by Caleb Dorsey. My birth date was August 24, 1840. My father, Abraham, was born in Kentucky around 1811 on the Phillips plantation.”

“Master Phillips had no children and felt that he had enough property to sustain his widow in the event of his death. He declared in his will, therefore, that if he died before his wife, his slaves should be set free and carried to a free state. Father Abraham and Master Phillips’ other slaves were set free before the war began.

“Aunt Nellie (her real name was Nancy) also was a slave. She and Abraham were on the same plantation. Her master had given her some money and she loaned it to Abraham to help him get his wife (Loyd’s mother), who was on an adjoining plantation. He had to pay $450 for her freedom.

“My family was like so many families whose members were torn apart during slavery, and paths to freedom were varied. Caleb Dorsey was my old slave owner. He was cruel and mean and old and feeble. Dorsey was bad. Morals on the plantation were bad. I was a small boy at the time, but I know liberties were taken with slaves. Dorsey was so mean to his colored slaves and also to his wife that she committed suicide by taking a gun and putting the muzzle under her throat and discharging the gun with her foot. Dorsey looked about for another wife, but he was so mean to his first wife that he found that it was not an easy task to find a second one. He died before finding a new wife.

“When Dorsey’s slaves gave out or were overcome by heat in the harvest field, Dorsey was so cruel that he would order them dragged to the woods. Many times, he would go out in the woods and try to lash them up with a cowhide. If any slave died in the woods he would not take time to bury them until night, and then he would dig a hole and throw them in.

“After the death of Dorsey, the estate was divided between his three heirs: two boys and one girl. The daughter was married to a slave owner by the name of Phil Barbour. The slaves were divided into three bunches and straws were drawn for us. My gang fell to the daughter who was General Phil Barbour’s wife, so Master Phil Barbour became my owner. He was mean as a dog, and it was from this new master’s plantation that I, Loyd, would make my escape to freedom.

“As stated, Phil Barbour was a cruel master and at times treated his slaves badly. An adjoining plantation was owned by Mr. Harboldt. The Harboldt plantation’s owner was by and large a good master. Mr. Harboldt was regarded as a high-class slaveholder with a 30-acre plantation. He was considered a good slave holder who allowed free Negroes and others to come onto his plantation and to marry his slaves with the understanding that the offspring would become his property.

“This was the condition under which I was able to marry Lucy, a slave on the Harboldt plantation. Lucy’s mother was a slave, and her father was a free man. But my master, Phil Barbour, was not one of those slave holders which allowed such practices. However, I was such a good housemate that Master Barbour made arrangements with Master Harboldt for me to come on his plantation and take as my wife his slave Lucy. She was my first wife, and we married at a very early age of 16 years. A total of nine children were born to this union, including one child who was born dead. Five of the children were born in slavery and died in slavery. Later when my wife and I escaped from slavery, the rest of our offspring were born in freedom.

The War: My Journey from Kentucky to Freedom. “

Fifteen or 20 of us made up our minds to run off of our different plantations. Sam and Pap and I were from the same plantation, and the other boys were on neighboring farms. All were single except me, and I hated to leave my wife.

“The man who took us across the river was a white man who was a fisherman who lived on the Indiana side. We crossed the river 3 or 4 miles east of Louisville. A recruiting officer was there to take charge of all who escaped. He received $10 per head for every one that he got to join the army. This recruiting officer acted as foreman and took those whom he secured to Pittsburgh to be examined free of charge. There were about 20 men in the group with me. All of the boys in this group were single — but me. I had three cousins in the group. The boys leaving Louisville for Pittsburgh had their ways paid by the government.

“After crossing the river, the recruiting officer took them to Pittsburgh to make up a regiment. There were about a dozen of the boys at Pittsburgh. The boys were examined and all passed as able-bodied men but me! I was the only one who did not pass the examination to go into the army. Typhoid fever, which settled in my leg, lamed me and disqualified me for service.

“When the other boys joined the army, they each gave me a dollar apiece to help me. They chipped in and made me up a purse of five dollars. They also gave me their citizen’s clothes. I went out to the edge of town, bought a couple of grain sacks, and filled them with the clothes given to me by the boys in my group. I also had a little money of my own that I had saved up.

“Before I left the rest of the bunch in the barracks at Pittsburgh where they were waiting to be sent to Philadelphia, I got someone to write a letter to master Barbour telling him that I could no longer be a slave and be dogged at and treated so cruel and mean. I discussed the mean things that he had done.

“After the war I went back on the old plantation to visit my birth place and found my old master Barbour still living. Barbour asked me why I would choose to come back on his place after writing such a letter. I apologized for writing the letter and told him that I didn’t mean anything by it.”

More information on the bicentennial can be found on Facebook at www.facebook.com/PauldingCounty200.

Next: The narrative history of Loyd Phillips’ journey to Paulding County will continue.

POSTED: 08/14/20 at 10:59 pm. FILED UNDER: News