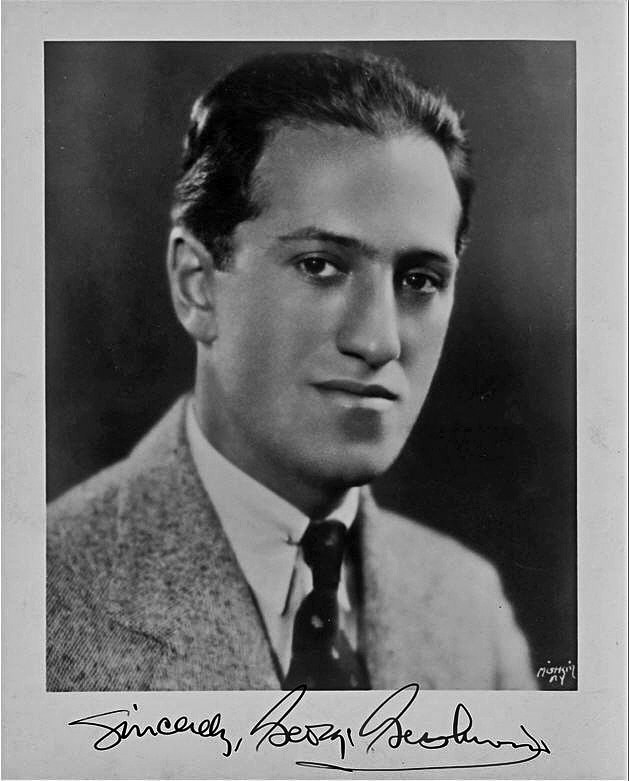

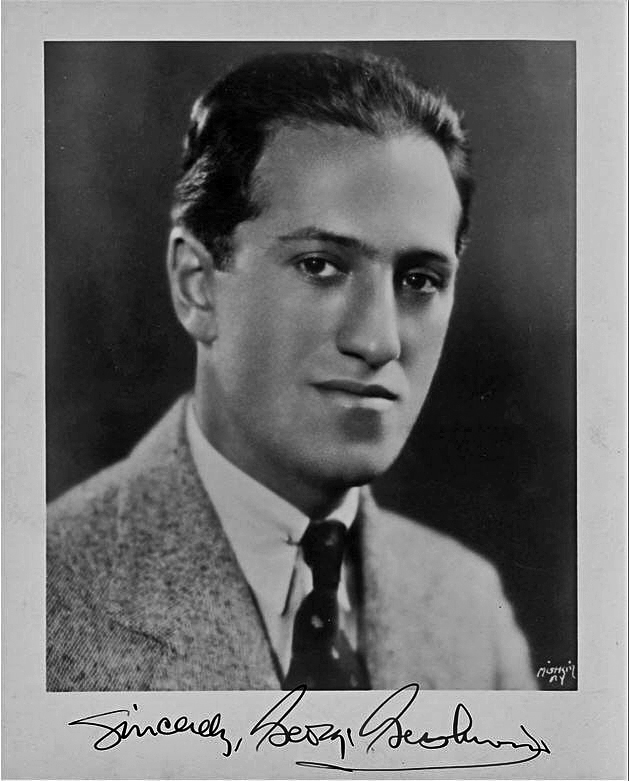

George Gershwin is one of the most important American composers of the 20th century. Born September 26, 1989, in Brooklyn, New York, he did not begin playing piano before the age of 12, but by his mid-teens, he had quit school and was earning a living in music as a “song-plugger” — pitching sheet music in department stores — on New York’s Tin Pan Alley. Eventually, he followed the example of his role model, Irving Berlin, and started composing his own music. In 1916, he published his first song, “When You Want ‘Em You Can’t Get ‘Em; When You Have ‘Em, You Don’t Want ‘Em,” for which he earned $5.

Gershwin is known as a major jazz innovator, and Amy C. Baumgartner writes that “in the transitory period following [World War I], it was George Gershwin who paved the way for jazz to become America’s only indigenous music.” However, Gershwin himself was reluctant to use the term “jazz” in conjunction with his music. The term does not appear in the title of any of his works. This reluctance seems to coincide with the composer’s general desire to avoid categorization or restriction of any kind in both music and life — as demonstrated by the fact that he worked for the stage and the screen and wrote anything from popular songs to concertos.

Towards the end of his life, Gershwin concluded that “Jazz is a word which has been used for at least five or six different types of music. It is really a conglomeration of many things … Ragtime, the blues, classicist and spiritual … An entire composition in jazz could not live.” In that same spirit, Gershwin’s music was as influenced by his own Jewish heritage and his well-documented humble beginnings. His career highlights the evolution of a very personal songwriting style.

This article attempts to retrace the steps of such an artistic evolution via six of his best-known compositions.

“Swanee” (1919)

“Swanee” (1919)

Having published his first song in 1916, Gershwin reached an early peak with the release of “Swanee,” with lyrics by Irving Caesar, three years later. It was Caesar who came up with the concept of a one-step with a vigorous striding rhythm that would be set on an American mythic land (as opposed to the popular one-step by Oliver Wallace and Harold Weeks, “Hindustan,” which was part of a trend of Middle Eastern and central Asian exotica of the time). In addition, “Swanee” was a parody of Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home,” a song from the mid-1800s that had since begun to fall out of favor due to its romanticizing of slavery.

“Swanee” works because of its lyric irony. There’s a contrast between the urgency of the verses and the cheerfulness of the chorus, with its protagonist’s keen determination to feel joyous. Says Gershwin: “I am happy to be told that the romance of [the “Southland”] is felt in it and that at the same time the spirit and energy of our United States is present. We are not all business or all romance, but a combination of the two characteristics, which I tried to unite in ‘Swanee’ and make represent the soul of this country.”

Published in 1919, “Swanee” is now mostly associated with singer Al Jolson, who first recorded it for Columbia in 1920. Within a year, the song had topped sheet music-sales of a million copies, bringing celebrity and riches to both Gershwin and Caesar – not bad for a song that was apparently written in ten minutes and completed in an hour.

Rhapsody in Blue (1924)

At 25, Gershwin wrote what is arguably his most famous work: Rhapsody in Blue. In the four years leading up to this immortal composition, he had been working on George White’s Scandals, a run of variety shows produced by theater impresario George White that were modeled on the popular Ziegfeld Follies, featuring songs, comedy, eccentric dancers and beautiful showgirls. Paul Whiteman, White’s bandleader at the time, was taken by Gershwin’s music. He particularly admired his “Blue Monday,” a one-act jazz opera, despite that show’s commercial failure.

Whiteman commissioned Gershwin’s jazz concerto as early as 1922 but did not give the young composer either deadline or guideline. Legend has it that Gershwin found out that his work was slated to premiere on February 12, 1924, at an event titled “An Experiment in Modern Music” just five weeks before the event. Thus, as he claimed, he hastily put together most of Rhapsody in Blue while on a train from New York to Boston, where he was traveling for the premiere a new musical of his.

“An Experiment in Modern Music” was also to feature compositions by Irving Berlin and Victor Herbert. There was no mistaking Whiteman’s ambitions and intentions – the venue he had selected for this event was New York’s Aeolian Hall and the audience would include such esteemed members of the classical music community as Sergei Rachmaninoff and Leopold Stokowski while, on the other hand, the jazz community remained largely ignored. Gershwin himself sat at the piano on this occasion. There had been previous attempts at jazz-influenced orchestral compositions, but they were widely regarded as underwhelming. The premiere of Rhapsody in Blue is now seen as announcing the beginning of the serious influence of American jazz in concert music worldwide.

“Someone to Watch Over Me” (1927) / “I Got Rhythm” (1928)

Jack Gibbons suggests that the premiere of Rhapsody in Blue was a personal landmark event for Gershwin that divides his early period, during which he built up his celebrity status, and his middle period, which took place between 1925 and 1930. During these years, Gershwin was extremely prolific and premiered such orchestral pieces as An American in Paris and Concerto in F, as well as theatre productions as Oh, Kay! (1926), Funny Face (1927) and Girl Crazy (1930). Yet, during this period, he still had a tendency to keep his orchestral work separate from his songwriting. He harbored two distinct identities, as shown, for example, by the diversity of the songs “Someone to Watch Over Me” and “I Got Rhythm.”

“Someone To Watch Over Me” was written for the 1927 musical Oh, Kay!, where it was introduced by actress Gertrude Lawrence, who also recorded a version of the song that same year. Here, Gershwin’s useful exuberance of the earlier songs is enhanced by more overly dramatic tones. The melodies have a more sweeping arch and the song seems to speak more directly to the heart of the listener. It is no coincidence that this period also affirmed his brother Ira as his songwriting partner. Ira preferred to work off a melody that George had already written, though George would be just as happy to change the music to fit any particularly captivating line.

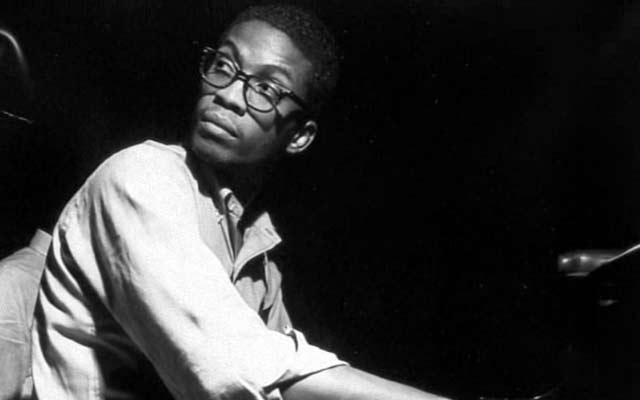

“I Got Rhythm” was written for the 1928 musical Girl Crazy and introduced by actress Ethel Merman. Unlike “Someone to Watch Over Me,” this song is fast and wild, but deceitfully conceals a sophistication and influences ranging from the stride to the music of Debussy. The chord progression and rhythm changes of this song predated and influenced many of the later styles of jazz and formed the foundation to many other popular songs of the bebop era.

“Summertime” (1934)

During his later period, Gershwin developed a style that was more personal, where the experimentation of his concertos influenced his works as a songwriter. The lines between his many identities as a composer are nowhere blurrier on his oeuvre than on what is arguably his most ambitious work — his 1934 “folk opera” Porgy and Bess. This was based on DuBose Heyward’s novel of the same name, which depicted life in a black tenement of Charleston, South Carolina, and the author had written the opera’s libretto plus the lyrics for over half of its songs.

Porgy and Bess had a tumultuous history and its greatness was not immediately recognized at its debut in 1935. It was initially a critical and financial failure, largely due to its racial themes. The final work was originally intended for the highbrow opera audience, but the opera critics were the first to attack it for its many leanings towards a popular music aesthetic. Despite this, Gershwin was proud of the work, defending his idea that “true music must repeat the thought and inspirations of the people and the times.”

Many of Porgy and Bess‘ songs achieved immediate popularity but the complete work only earned its real approval after it was revised in a 1940 Theater Guild presentation that better suited popular tastes. This presentation resulted in a marked reinterest of interpretations of the songs from the original libretto by countless jazz artists, and “Summertime” in particular is now one of the most covered songs of all time.

“Shall We Dance” (1937)

After Porgy and Bess, Gershwin moved to Hollywood and was hired to write music for the movies of the iconic duo of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. It was in Hollywood that Gershwin arguably reached his peak as a songwriter. The music for Shall We Dance, which was to be the first full Gershwin score for a Hollywood picture, is still steeped in the black culture and black music of Porgy and Bess, but also flirts with the melodic sophistication of classical music.

For example, the title track from the movie, performed by Astaire, shows such complexity as well as his trust in the taste of the mass audience. He once said he believed “the majority has much better taste and understanding not only of music but of any of the arts than it is credited with having. It is not the few knowing ones whose opinion make any work of art great. It is the judgment of the great mass that finally decides.”

Other songs from the soundtrack of Shall We Dance, from “They Can’t Take That Away from Me” to “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off” also proved that, by now, Gershwin had reached a peak and had perfected a personal style of songwriting, which was just as influenced by the culture that surrounded him as it was influenced from his own seemingly endless imagination.

Sadly, in the beginning of 1937, his health rapidly began to deteriorate and he died during surgery to remove a malignant brain tumor. He was only 38. Before he died, he completed his last musical composition, “Love Is Here to Stay.”

Like this article? Get more when you subscribe.

“Swanee” (1919)

Having published his first song in 1916, Gershwin reached an early peak with the release of “Swanee,” with lyrics by Irving Caesar, three years later. It was Caesar who came up with the concept of a one-step with a vigorous striding rhythm that would be set on an American mythic land (as opposed to the popular one-step by Oliver Wallace and Harold Weeks, “Hindustan,” which was part of a trend of Middle Eastern and central Asian exotica of the time). In addition, “Swanee” was a parody of Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home,” a song from the mid-1800s that had since begun to fall out of favor due to its romanticizing of slavery.

“Swanee” works because of its lyric irony. There’s a contrast between the urgency of the verses and the cheerfulness of the chorus, with its protagonist’s keen determination to feel joyous. Says Gershwin: “I am happy to be told that the romance of [the “Southland”] is felt in it and that at the same time the spirit and energy of our United States is present. We are not all business or all romance, but a combination of the two characteristics, which I tried to unite in ‘Swanee’ and make represent the soul of this country."

Published in 1919, "Swanee" is now mostly associated with singer Al Jolson, who first recorded it for Columbia in 1920. Within a year, the song had topped sheet music-sales of a million copies, bringing celebrity and riches to both Gershwin and Caesar - not bad for a song that was apparently written in ten minutes and completed in an hour.

Rhapsody in Blue (1924)

At 25, Gershwin wrote what is arguably his most famous work: Rhapsody in Blue. In the four years leading up to this immortal composition, he had been working on George White's Scandals, a run of variety shows produced by theater impresario George White that were modeled on the popular Ziegfeld Follies, featuring songs, comedy, eccentric dancers and beautiful showgirls. Paul Whiteman, White's bandleader at the time, was taken by Gershwin's music. He particularly admired his "Blue Monday," a one-act jazz opera, despite that show's commercial failure.

Whiteman commissioned Gershwin's jazz concerto as early as 1922 but did not give the young composer either deadline or guideline. Legend has it that Gershwin found out that his work was slated to premiere on February 12, 1924, at an event titled "An Experiment in Modern Music" just five weeks before the event. Thus, as he claimed, he hastily put together most of Rhapsody in Blue while on a train from New York to Boston, where he was traveling for the premiere a new musical of his.

"An Experiment in Modern Music" was also to feature compositions by Irving Berlin and Victor Herbert. There was no mistaking Whiteman's ambitions and intentions - the venue he had selected for this event was New York's Aeolian Hall and the audience would include such esteemed members of the classical music community as Sergei Rachmaninoff and Leopold Stokowski while, on the other hand, the jazz community remained largely ignored. Gershwin himself sat at the piano on this occasion. There had been previous attempts at jazz-influenced orchestral compositions, but they were widely regarded as underwhelming. The premiere of Rhapsody in Blue is now seen as announcing the beginning of the serious influence of American jazz in concert music worldwide.

“Someone to Watch Over Me” (1927) / “I Got Rhythm” (1928)

Jack Gibbons suggests that the premiere of Rhapsody in Blue was a personal landmark event for Gershwin that divides his early period, during which he built up his celebrity status, and his middle period, which took place between 1925 and 1930. During these years, Gershwin was extremely prolific and premiered such orchestral pieces as An American in Paris and Concerto in F, as well as theatre productions as Oh, Kay! (1926), Funny Face (1927) and Girl Crazy (1930). Yet, during this period, he still had a tendency to keep his orchestral work separate from his songwriting. He harbored two distinct identities, as shown, for example, by the diversity of the songs "Someone to Watch Over Me" and "I Got Rhythm."

"Someone To Watch Over Me" was written for the 1927 musical Oh, Kay!, where it was introduced by actress Gertrude Lawrence, who also recorded a version of the song that same year. Here, Gershwin's useful exuberance of the earlier songs is enhanced by more overly dramatic tones. The melodies have a more sweeping arch and the song seems to speak more directly to the heart of the listener. It is no coincidence that this period also affirmed his brother Ira as his songwriting partner. Ira preferred to work off a melody that George had already written, though George would be just as happy to change the music to fit any particularly captivating line.

"I Got Rhythm" was written for the 1928 musical Girl Crazy and introduced by actress Ethel Merman. Unlike "Someone to Watch Over Me," this song is fast and wild, but deceitfully conceals a sophistication and influences ranging from the stride to the music of Debussy. The chord progression and rhythm changes of this song predated and influenced many of the later styles of jazz and formed the foundation to many other popular songs of the bebop era.

“Summertime” (1934)

During his later period, Gershwin developed a style that was more personal, where the experimentation of his concertos influenced his works as a songwriter. The lines between his many identities as a composer are nowhere blurrier on his oeuvre than on what is arguably his most ambitious work — his 1934 "folk opera" Porgy and Bess. This was based on DuBose Heyward's novel of the same name, which depicted life in a black tenement of Charleston, South Carolina, and the author had written the opera's libretto plus the lyrics for over half of its songs.

Porgy and Bess had a tumultuous history and its greatness was not immediately recognized at its debut in 1935. It was initially a critical and financial failure, largely due to its racial themes. The final work was originally intended for the highbrow opera audience, but the opera critics were the first to attack it for its many leanings towards a popular music aesthetic. Despite this, Gershwin was proud of the work, defending his idea that "true music must repeat the thought and inspirations of the people and the times."

Many of Porgy and Bess' songs achieved immediate popularity but the complete work only earned its real approval after it was revised in a 1940 Theater Guild presentation that better suited popular tastes. This presentation resulted in a marked reinterest of interpretations of the songs from the original libretto by countless jazz artists, and "Summertime" in particular is now one of the most covered songs of all time.

“Shall We Dance” (1937)

After Porgy and Bess, Gershwin moved to Hollywood and was hired to write music for the movies of the iconic duo of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. It was in Hollywood that Gershwin arguably reached his peak as a songwriter. The music for Shall We Dance, which was to be the first full Gershwin score for a Hollywood picture, is still steeped in the black culture and black music of Porgy and Bess, but also flirts with the melodic sophistication of classical music.

For example, the title track from the movie, performed by Astaire, shows such complexity as well as his trust in the taste of the mass audience. He once said he believed "the majority has much better taste and understanding not only of music but of any of the arts than it is credited with having. It is not the few knowing ones whose opinion make any work of art great. It is the judgment of the great mass that finally decides."

Other songs from the soundtrack of Shall We Dance, from "They Can't Take That Away from Me" to "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off" also proved that, by now, Gershwin had reached a peak and had perfected a personal style of songwriting, which was just as influenced by the culture that surrounded him as it was influenced from his own seemingly endless imagination.

Sadly, in the beginning of 1937, his health rapidly began to deteriorate and he died during surgery to remove a malignant brain tumor. He was only 38. Before he died, he completed his last musical composition, "Love Is Here to Stay."

Like this article? Get more when you

“Swanee” (1919)

Having published his first song in 1916, Gershwin reached an early peak with the release of “Swanee,” with lyrics by Irving Caesar, three years later. It was Caesar who came up with the concept of a one-step with a vigorous striding rhythm that would be set on an American mythic land (as opposed to the popular one-step by Oliver Wallace and Harold Weeks, “Hindustan,” which was part of a trend of Middle Eastern and central Asian exotica of the time). In addition, “Swanee” was a parody of Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home,” a song from the mid-1800s that had since begun to fall out of favor due to its romanticizing of slavery.

“Swanee” works because of its lyric irony. There’s a contrast between the urgency of the verses and the cheerfulness of the chorus, with its protagonist’s keen determination to feel joyous. Says Gershwin: “I am happy to be told that the romance of [the “Southland”] is felt in it and that at the same time the spirit and energy of our United States is present. We are not all business or all romance, but a combination of the two characteristics, which I tried to unite in ‘Swanee’ and make represent the soul of this country."

Published in 1919, "Swanee" is now mostly associated with singer Al Jolson, who first recorded it for Columbia in 1920. Within a year, the song had topped sheet music-sales of a million copies, bringing celebrity and riches to both Gershwin and Caesar - not bad for a song that was apparently written in ten minutes and completed in an hour.

Rhapsody in Blue (1924)

At 25, Gershwin wrote what is arguably his most famous work: Rhapsody in Blue. In the four years leading up to this immortal composition, he had been working on George White's Scandals, a run of variety shows produced by theater impresario George White that were modeled on the popular Ziegfeld Follies, featuring songs, comedy, eccentric dancers and beautiful showgirls. Paul Whiteman, White's bandleader at the time, was taken by Gershwin's music. He particularly admired his "Blue Monday," a one-act jazz opera, despite that show's commercial failure.

Whiteman commissioned Gershwin's jazz concerto as early as 1922 but did not give the young composer either deadline or guideline. Legend has it that Gershwin found out that his work was slated to premiere on February 12, 1924, at an event titled "An Experiment in Modern Music" just five weeks before the event. Thus, as he claimed, he hastily put together most of Rhapsody in Blue while on a train from New York to Boston, where he was traveling for the premiere a new musical of his.

"An Experiment in Modern Music" was also to feature compositions by Irving Berlin and Victor Herbert. There was no mistaking Whiteman's ambitions and intentions - the venue he had selected for this event was New York's Aeolian Hall and the audience would include such esteemed members of the classical music community as Sergei Rachmaninoff and Leopold Stokowski while, on the other hand, the jazz community remained largely ignored. Gershwin himself sat at the piano on this occasion. There had been previous attempts at jazz-influenced orchestral compositions, but they were widely regarded as underwhelming. The premiere of Rhapsody in Blue is now seen as announcing the beginning of the serious influence of American jazz in concert music worldwide.

“Someone to Watch Over Me” (1927) / “I Got Rhythm” (1928)

Jack Gibbons suggests that the premiere of Rhapsody in Blue was a personal landmark event for Gershwin that divides his early period, during which he built up his celebrity status, and his middle period, which took place between 1925 and 1930. During these years, Gershwin was extremely prolific and premiered such orchestral pieces as An American in Paris and Concerto in F, as well as theatre productions as Oh, Kay! (1926), Funny Face (1927) and Girl Crazy (1930). Yet, during this period, he still had a tendency to keep his orchestral work separate from his songwriting. He harbored two distinct identities, as shown, for example, by the diversity of the songs "Someone to Watch Over Me" and "I Got Rhythm."

"Someone To Watch Over Me" was written for the 1927 musical Oh, Kay!, where it was introduced by actress Gertrude Lawrence, who also recorded a version of the song that same year. Here, Gershwin's useful exuberance of the earlier songs is enhanced by more overly dramatic tones. The melodies have a more sweeping arch and the song seems to speak more directly to the heart of the listener. It is no coincidence that this period also affirmed his brother Ira as his songwriting partner. Ira preferred to work off a melody that George had already written, though George would be just as happy to change the music to fit any particularly captivating line.

"I Got Rhythm" was written for the 1928 musical Girl Crazy and introduced by actress Ethel Merman. Unlike "Someone to Watch Over Me," this song is fast and wild, but deceitfully conceals a sophistication and influences ranging from the stride to the music of Debussy. The chord progression and rhythm changes of this song predated and influenced many of the later styles of jazz and formed the foundation to many other popular songs of the bebop era.

“Summertime” (1934)

During his later period, Gershwin developed a style that was more personal, where the experimentation of his concertos influenced his works as a songwriter. The lines between his many identities as a composer are nowhere blurrier on his oeuvre than on what is arguably his most ambitious work — his 1934 "folk opera" Porgy and Bess. This was based on DuBose Heyward's novel of the same name, which depicted life in a black tenement of Charleston, South Carolina, and the author had written the opera's libretto plus the lyrics for over half of its songs.

Porgy and Bess had a tumultuous history and its greatness was not immediately recognized at its debut in 1935. It was initially a critical and financial failure, largely due to its racial themes. The final work was originally intended for the highbrow opera audience, but the opera critics were the first to attack it for its many leanings towards a popular music aesthetic. Despite this, Gershwin was proud of the work, defending his idea that "true music must repeat the thought and inspirations of the people and the times."

Many of Porgy and Bess' songs achieved immediate popularity but the complete work only earned its real approval after it was revised in a 1940 Theater Guild presentation that better suited popular tastes. This presentation resulted in a marked reinterest of interpretations of the songs from the original libretto by countless jazz artists, and "Summertime" in particular is now one of the most covered songs of all time.

“Shall We Dance” (1937)

After Porgy and Bess, Gershwin moved to Hollywood and was hired to write music for the movies of the iconic duo of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. It was in Hollywood that Gershwin arguably reached his peak as a songwriter. The music for Shall We Dance, which was to be the first full Gershwin score for a Hollywood picture, is still steeped in the black culture and black music of Porgy and Bess, but also flirts with the melodic sophistication of classical music.

For example, the title track from the movie, performed by Astaire, shows such complexity as well as his trust in the taste of the mass audience. He once said he believed "the majority has much better taste and understanding not only of music but of any of the arts than it is credited with having. It is not the few knowing ones whose opinion make any work of art great. It is the judgment of the great mass that finally decides."

Other songs from the soundtrack of Shall We Dance, from "They Can't Take That Away from Me" to "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off" also proved that, by now, Gershwin had reached a peak and had perfected a personal style of songwriting, which was just as influenced by the culture that surrounded him as it was influenced from his own seemingly endless imagination.

Sadly, in the beginning of 1937, his health rapidly began to deteriorate and he died during surgery to remove a malignant brain tumor. He was only 38. Before he died, he completed his last musical composition, "Love Is Here to Stay."

Like this article? Get more when you