In Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory, a literary study of World War 1, Fussell writes that the advent of war was, in “the modern imagination,” a transition from “felicity to despair, pastoral to anti-pastoral.” Fussell was making a point about how the Great War was a launching pad for the modern age, a bloody chasm dividing the genteel old world of the 19th century from the blasted wastelands of the 20th. Stories like the assassination of Gaston Calmette, editor for France’s storied newspaper, Le Figaro, are bloody enough, but they still feel like artifacts of that pastoral time.

Yet the tale of Calmette’s death at the hands of a desperate woman may also be cautionary. Considering the kinds of scandals yellow journalism can still stir up in Paris today, it’s surprising there haven’t been more Calmettes in our “anti-pastoral” age. If his death had been the beginning of a trend, no one working for TMZ could go out in public without a bodyguard.

As reported in English-speaking press on March 17, 1914, Gaston Calmette died at the hands of Henriette Caillaux, the second wife of France’s minister of finance at that time, Joseph Caillaux.

Le Figaro had been nibbling at the minister’s heels for years. Calmette had often accused Caillaux of corruption and twisted the knife earlier in March, 1914 by publishing love letters Caillaux wrote to Mme. Caillaux in 1901. The pair were still married to others at the time.

When Mme. Caillaux arrived at paper’s office on March 16, Calmette was meeting with author Paul Bourget. An article published in several U.S. papers the following day stated that on seeing that his friend had received the woman’s calling card, Bourget said, “Do not see her.”

“She is a woman,” Calmette said, “I must receive her.”

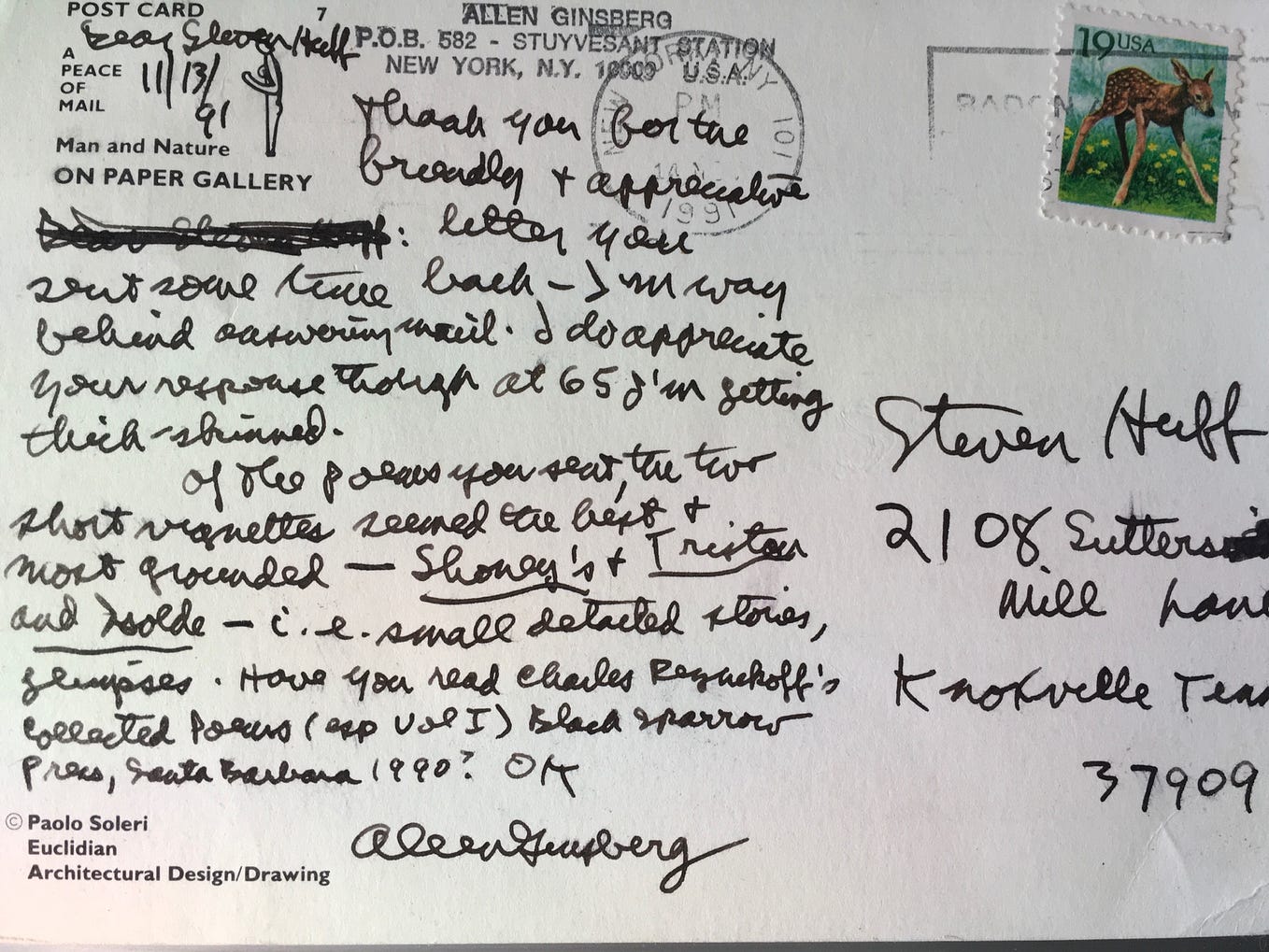

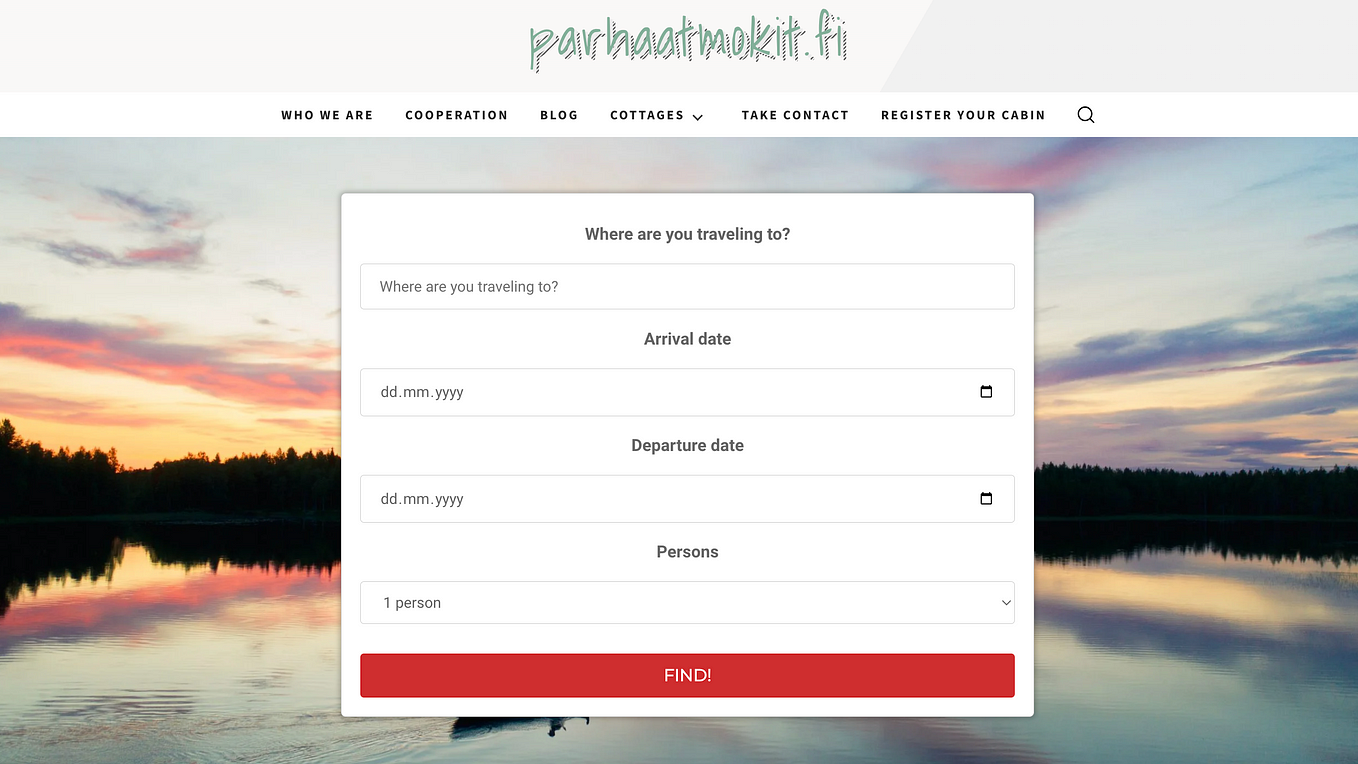

His old world courtliness was his undoing. As depicted in the image above, which was the cover for one of many French publications that reported on the case, Mme. Caillaux calmly entered Calmette’s office, drew a pistol concealed in a hand warmer, and shot him at least 5 times.

As Calmette fell and she was restrained by others, Mme. Caillaux reportedly said, “Ne me touchez pas, je suis une dame”— “Don’t touch me. I’m a lady.”

Le Figaro staffers claimed that Calmette’s final statement was, “I only did my duty. I have no personal malice.”

Calmette’s killer, if reports are to be believed, never lost her cool, or as the unsubtle writer of the English language article put it, “her wonderful calmness.”

Mme. Caillaux later said she “wanted to wound” the editor, that she “didn’t mean to kill him.” She said she regretted her actions. “All I wanted,” she said, “was to give him a lesson.”

It was a remarkable case, and remained in the news for months to come. The strange thing to someone reading about it today is the deeply embedded paternalism and misogyny of the times kept Henriette Caillaux from life—or a significant amount of time—in prison. From Murderpedia: “[Mme. Caillaux] was defended by the prominent attorney Fernand-Gustave-Gaston Labori (1860-1917); he convinced the jury that her crime, which she did not deny, was not a premeditated act but that her uncontrollable female emotions resulted in a crime of passion.”

Mme. Caillaux was acquitted. She went on to become a respected scholar and author. She died in 1943.

July 28, 1914, the day of her acquittal, was the same day Austria-Hungary declared war with Serbia, launching World War 1. The world, run by those men who prided themselves on supposed emotional control, was soon to be mired in blood, mud, and flames.