‘The cinema had mice but it felt like being at the ringside’

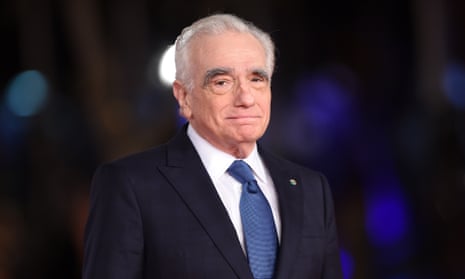

Steve McQueen

Scorsese is so good at introduction scenes. I love the one in Mean Streets, where De Niro comes into the bar for the first time. Harvey Keitel is watching him, it’s all in slo-mo, Jumping Jack Flash on the soundtrack. It’s one of the most perfect introductions to a character I’ve ever seen: a beautiful piece of music and imagery and choreography.

I also love De Niro waiting for Joe Pesci in the desert in Casino. Is Pesci his friend, or his enemy? He doesn’t know yet. It’s absolutely incredible, so beautiful: the car passing through the sunglasses, the music – another introduction, another uncertainty about what will occur. There’s an anticipation; you’re in limbo.

And there’s the fights in Raging Bull. I remember seeing that the first time in the Scala cinema in London in the late 80s: there were mice running around, litter everywhere, and it felt like being at the ringside. I remember the sound of the hitting and the punching. It’s very heavy, very visceral.

There’s a dynamism and physicality in Scorsese films which has informed my work. As a visual artist, I make stuff – it’s not about the thinking, it’s actually about the doing. It happens in the moment: you can write something, you can think of something, but on the set you actually have to make it. When I’m shooting a film, I’m not thinking about Tarkovsky or Kieslowski or Bergman or whatever, I’m thinking about how do my best in the moment – and I can appreciate that in his films. Scorsese is a maker: a film-maker rather than a director.

‘Everything is wrong, yet it’s even romantic’

Lynne Ramsay

Scorsese is the master of memorable scenes and it’s difficult to choose a favourite. “You talking to me?”, “You think I’m funny?”, the dead-end phone call to Betsy in Taxi Driver and the track to an empty hall when she’s not interested. The Alka-Seltzer fizzing in the glass in the diner. The body cam in Mean Streets. Too many to mention – all brilliant and so cinematic.

There is something about misunderstanding the world or the situation Scorsese captures that’s so recognisable and so human. ‘‘Every man has to go through hell to reach his paradise,” says Max Cady, played by Robert De Niro in Cape Fear. In that film, teenage girl Danielle (Juliette Lewis) tests her burgeoning sexuality against Max’s menacing and manipulating adult force.

The scene between them in the gym is brilliantly realised, and nail-bitingly uncomfortable. Watching it, I felt transported back to this time, so unsure of the world and trying to navigate its rules. Everything is wrong, yet innocence and psychopathy somehow sit together in odd unison; it’s even romantic (in her eyes).

Max: You thought about me last night, didn’t you?

Danielle: Yes, I did.

Max: I think I might have found a companion for that long walk to the light.

The first take was used and Lewis knew De Niro might do something unexpected – but not about his thumb, which he uses to caress her cheek, before slipping it into her mouth. She brilliantly holds her own and captures this uncertain age stunningly.

A lamb and a wolf. Yet the lamb doesn’t realise she’s a lamb.

‘It is one of the most erotic moments in cinema ever’

Luca Guadagnino

For me, Scorsese’s work is paramount and a point of reference I go back to constantly, for the incredible power and intelligence he’s displayed throughout his career.

The first sequence I want to point to is the finale of The Last Temptation of Christ. It is the movie of Scorsese’s that I love the most. I’m not talking about the narrative of Jesus Christ being put on the cross and then being summoned to the life of a normal person, and the delirium he has with the devil. I am talking about the last minute of the movie, where he asks why God has abandoned him. He then finds himself back on the cross, and the camera has an amazing moment, a super-Scorsesean push towards Jesus, waking him up, and waking us up, from the dream, and then finally he says: “It is accomplished.”

The camera lingers on Jesus, and then, to show him ascend to the heavens, Scorsese does one of the most beautiful and profound cinema gestures ever conceived: basically, he flickers the film, as if the film becomes a trip of light and is the way his Jesus goes to heaven. Incredible, so beautiful. The idea that he can put together the life of Christ from the Kazantzakis novel with his own life in the land of cinema, and bring Jesus to heaven through the power of cinema, it is sublime. It reminds me also of the way we ascend to heaven at the end of the Shine a Light documentary about the Rolling Stones, when the camera goes up, up, up. Those kind of moments are just unbeatable and amazing.

The other sequence I want to discuss is in The Age of Innocence, when Newland Archer and Countess Olenska, who have inexorably been falling in love throughout the entire movie, but always repressing what they feel, find themselves alone in a carriage. Newland opens the countess’s glove and unbuttons it and then opens up the piece of leather that the glove is made of with his fingers and kisses her wrist. This detail is almost like him opening her vagina with his own bare hands – it is one of the greatest and most erotic moments in cinema ever.

It takes masterful details to do this kind of stuff – Scorsese is a master, and I salute him and celebrate him. I don’t see him as a violent film-maker; I think he’s unsentimental – as every real film-maker should be. He explores humankind and what comes with that, including violence. The Age of Innocence in my view is one of the most violent movies ever made: it is about repression and oppression. To understand its display of violence, think of the scene at the end of the movie with the great dinner to celebrate the countess going back to Europe. Everybody present knows they are making sure her and Newland are going to be separated for ever, and they do it by hosting the most gorgeous meal. Marty goes from the bottom of the table all the way to the top showing the grandeur of the plan created by these monsters, and the solitude of these two. The doom they have to face, to be separated by the riles of society, losing innocence for ever. It is beautiful.

What I have learned from Scorsese is how he is always relentless in exploring every single detail, contradiction and power within a character. At first I was looking to find the kinetic energy in his way of editing movies, but I soon realised it was unmatchable. But with more maturity I discovered that for all the incredible brio of his style, he is a humanist who thinks very deeply about human nature. It’s constant lesson I try to learn from him.

‘I was living peacefully in Tokyo but was one with the immigrant boxer’

Takashi Miike

Soon after the film begins and having been defeated unfairly in a fight against Sugar Ray Robinson, the scene moves to LaMotta’s house. Arguing with his wife as she cooks the steak, LaMotta tells his brother, who tries to intervene: “Hit me in the face.”

This scene made me experience the miracle of film. I, who was from a different country, time, and environment, was able to hear LaMotta’s screaming within his mind: his irritation and uncontrollable anger which has nowhere to go. I, who was living peacefully in Tokyo, could be one with the immigrant boxer. This is a brilliant scene. Today, when so many scripts seem to consist of dialogue, the value of this film has been enhanced.

‘Scorsese’s most lucid expression of love for his medium and his religion’

Ari Aster

The final 40 minutes of The Last Temptation of Christ are among the richest and most emotionally complex of any film I’ve seen – wilfully perverse, ambiguous in ways that persist in haunting me, and dense with wonders. There’s the Sturm und Drang of Christ’s earth-shaking moment of doubt (“Father! Why have you forsaken me?”), followed by the ethereal quiet that inaugurates his tour through an unlived life; there’s the tenderness of Christ’s guardian angel (Satan in the uncanny disguise of a benevolent child) kissing Jesus’s wounds after releasing him from the cross; the shock and sublimity of Jesus having a child with Mary and the subsequent strangeness and mystery of his coupling with the sisters of Lazarus.

And, of course, there’s the undersung glory of Harvey Keitel as Judas (a part he first played in Mean Streets), in some ways the film’s hero, as tortured as Christ but saddled with the more difficult job. The complexity of Judas here is only right, as the Judas figure must be the most recurrent and central object of fascination in Scorsese’s body of work – reaching its apogee with the perpetual traitor Kichijiro in Silence, one of the great films of this century and still waiting for the celebration it deserves.

But nothing beats the final moment of Christ’s ecstatic death – “It is accomplished!” – during which the film rolls out of the camera, unleashing a flurry of heavenly, emulsive flares, accompanied by a wave of wailing mourners that gives way to Peter Gabriel’s triumphant and rhapsodic final cue. The credits play over an orange screen, evoking fire but also celebrating the film’s pop sensibility; this orange is a freeze-frame of the film-rollout, accidental and God-given, and it feels like Scorsese’s most lucid expression of love for his medium and fervency for his religion.

Despite this film’s commitment to Kazantzakis’ book’s more incendiary ideas, every one of Scorsese’s choices feels informed by the deepest, most engaged faith. Even those controversial New York accents contribute to the film’s immediacy; after all, as Scorsese has pointed out, “the Galileans had such strong accents that they were made fun of in Jerusalem”. For this director – the most serious and morally curious of Catholic artists – to take on the story of Christ could never be a step taken lightly, and the wealth of personal touches are beautifully judged and absolutely right. And the result is one of the most spiritually inquisitive and truly transcendent films ever made.

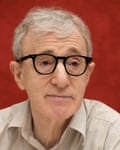

‘Marty is a poet of the dark side of Manhattan’

Woody Allen

I like all Marty’s movies, but Goodfellas is I think one of the finest American films that has ever been made. It’s just a wonderful, wonderful movie. I don’t really think about outstanding individual scenes, I just love the whole picture: the way it was shot, the casting, the performances – it’s a superb piece of work. When I first saw it I just loved it. I saw all his pictures. Marty is one of the few directors whose movies are worthwhile to watch all the time.

We’re very different. Marty is a poet of the dark side of Manhattan, and I have been someone who has seen the city in a much more romantic kind of way. I guess the difference is because Marty got his impressions of Manhattan from growing up downtown, and I got my impressions from Hollywood movies. His impressions of New York are very real and very gritty and very accurate, while mine have always been heavily influenced by ideas of a New York that may or may not have even existed. Maybe it did exist as reality – but I wouldn’t have known; I was squirrelled away in Brooklyn. Marty got a real taste of the lower depths in Little Italy, and made films about it with great excitement and accuracy.

In 1997 the New York Times set up an interview discussion with Marty and myself and they were very surprised that the two of us didn’t really know each other before that. In fact it turned out he only lives a few blocks from me on the Upper East Side. But I can safely say that we never see each other. I only have the finest feelings for him, but our social life has never brought us together in any way.

‘What could someone else’s film teach a genius like me?’

Abel Ferrara

So it’s write about your teacher time again – at least this time it’s for a birthday and not a funeral. I was a kick-ass film student in a big art school outside NYC and I had been making films since I was 16, and I was all about making them and not watching them. What could another person’s film teach me?

One day someone told me there was a movie I should see called Mean Streets, and that same day another person said I should check out The Conformist. So I rode alone into NYC down Route 684 on a beautiful fall day back when you could park in front of a theatre on 57th Street. They were playing right across the street from each other, so I could walk right out of Scorsese and right into Bertolucci.

after newsletter promotion

The ride home was up the Palisades Parkway because I needed to get to my homeboys in Peekskill to decompress, to figure out what it was I just experienced. It was dark now and raining and the leaves were blowing all over the road. And through the windshield wipers of my car were the images, the shots, the music. I knew everything we did and were doing meant nothing. Was it my Pirellis on that slick road or my voice asking: how the fuck do you do that?

‘He has launched infinite echoes across modern cinema’

Edgar Wright

It’s difficult to express how much Scorsese means to me. It isn’t just that his cinema inspires me on a daily basis, it’s that, through his advocacy, pretty much all cinema inspires me.

It’s no stretch to say that Scorsese is undoubtedly one of the most influential and inventive living directors, one who has himself launched infinite echoes across modern cinema. Yet he always takes the time to credit and pay respect to his own inspirations, especially when they are from unlikely or even dismissed film-makers. To see him mention Hammer Horror in the same breath as David Lean makes my heart swell. He is a maker of cinema who never stopped being a cinema fan.

Over his diverse filmography (anyone who says he just makes gangster films is a fool), I can’t even begin to detail the effect he’s had on my enjoyment, appreciation and knowledge of the form. I never went to film school, but through his work and detailed discussions about his own process as well as the artistry of others, I feel like he constantly provides me with a one-man education of the medium.

To name one specific scene of his that moves me is difficult, but even a less famous entry like After Hours includes camera movements, sharp edits and musical choices that were burned into my brain after a single viewing as a teenager. We’re lucky to have him on this Earth, not just for his own films, but for everything he’s done for the history and future of cinema.

‘It’s beyond beauty’

Carol Morley

In Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, a handheld single shot follows newly widowed waitress Alice (Ellen Burstyn), as she breaks down in tears and is guided by her fellow waitress Flo (Diane Ladd) out of the dining room, through the work station, into the back kitchen, into the brightness of the cluttered yard, and finally, after the sensory overload of those places, into the relative peace and quiet of the blue painted restroom – the smallest space to shoot a scene.

Here, as they shut the door on the domestic obligations, the camera finds stability, and Alice and Flo, squashed against the paper towel dispenser, the toilet and the barred narrow window, begin to share difficult details of their lives. This newly sanctified space can’t quite belong entirely to them, though, because life is just too imperfect. The diner owner bursts through the door to a finely tuned wisecrack from Flo, and the film itself cross-cuts repeatedly from the growing intimacy between the two waitresses in the restroom to the chaos in the diner that has resulted from their absence.

This sequence for me demonstrates what Scorsese is so brilliant at, for being beyond beauty and the prettifying and the stylistic hollow places where a film can end up brittle and cold. It’s all a bit messy and rides a lot of tones, which is much more interesting and truthful. And I love how he adores his actors, how he will do anything for them, and is prepared to reach into deep places to give us characters who struggle to relate emotionally, while all they have is their emotions. He makes everything personal.

Scorsese’s movies pass through my mind and heart at regular intervals. His own films, his love of films, the way movies have shaped his life, his belief in saving movies that are at risk of disappearing from history; these are what make him for me such a true hero of cinema.

‘There’s no false emotional catharsis or celebrity endorsement’

Kevin Macdonald

An unbroken two-and-a-half minute shot featuring vibrant characters, Italian food and a journey through a kitchen … no, this is not the legendary Goodfellas restaurant scene. The opening shot of Scorsese’s 1974 documentary Italianamerican tells you everything you could ever possibly want to know about who this director is and what his influences are.

It’s a 45-minute film about his parents, Catherine and Charles, and never leaves the modest confines of their Manhattan apartment with its plastic-covered furnishings and plentiful tchotchkes. What strikes you immediately is how completely, unselfconsciously themselves these characters are – and yet so completely the archetypes of every goodfella to come. Even the trademark mix of humour and impending violence is there in prototype. When Catherine tells her husband to move down the couch (“Why you so far from me? Get closer. No, you come here …”) the resigned expression on Charles’s face suggests a fear of being “whacked” (in a marital sense) if he doesn’t obey. The intonation of the dialogue is so familiar to anyone who has seen a Scorsese movie. When Catherine asks her son: “I’m supposed to be talkin’ to you?” I don’t think I’m alone in hearing the rhythms of De Niro interrogating himself in front of the mirror in Taxi Driver.

In its own unpretentious way Italianamerican is a rigorous formal statement. This is real cinéma vérité. There are no editing sleights of hand. No attempt to cut out the messy bits, the out of focus bits; no desire to “sex up” the subject. It speaks of a profound humanism – something you can sense in the director’s later documentary portraits of musicians – Bob Dylan: No Direction Home, Living in the Material World – and on the history of cinema (My Voyage to Italy). The director wants to show you this is why this person is so important and interesting. There’s no false emotional catharsis or celebrity endorsement. It’s like talking to the most generous-minded and encyclopaedically knowledgable fan.

Yes, Scorsese is a brilliant stylist, a creator of mind-blowing shots – but it’s this profound humanism that, to me, makes him the greatest.

‘That’s what cinema is all about – creating moments that stick with people’

Tim Burton

When I think of Scorsese, I think of all the uncomfortable moments in his films. I think he’s a master of that. Like the King of Comedy, when Robert De Niro goes to Jerry Lewis’s house uninvited. It’s excruciating.

Maybe Goodfellas is the best example of how he does that so well. That unforgettable scene in the restaurant when the tension is building between Pesci and Ray Liotta. “Funny? Funny how? Like I’m a clown? I amuse you?” That’s the moment you remember. And that’s what cinema is all about – creating moments that stick with people.

Funnily enough, from my experience Marty is almost the opposite in real life. I met him once and he made me feel totally at ease. He was such an enthusiastic, knowledgable guy; he mentioned he had a 35mm print of Beetlejuice in his library. When you meet him you feel his passion for film.

‘Paul Pelosi was home in bed. Iris is stoned, in over her head’

Kelly Reichardt

I’m revisiting Taxi Driver the day after a man broke into the home of Nancy and Paul Pelosi. It’s raining outside. Steam is coming up through the manhole on Third Avenue. It’s almost election time. At the Palantine campaign headquarters, Albert Brooks is in a pale yellow shirt with his feet on the desk. He’s on the phone with a button-maker. WE are the people v We ARE the people. The buttons are wrong, but he doesn’t want to fight. “We don’t pay for the buttons. We throw the buttons away,” Brooks tells the button-maker.

A yellow taxi is loitering outside the glass doors at the campaign headquarters. Travis Bickle, the Vietnam vet behind the wheel, wants someone to come clean up the city. Sometimes Travis goes out and smells it and gets a headache it’s so bad. He keeps staring through the glass at Cybill Shepherd with her blond hair and blue eyes. “Look over there. Notice anything?” she asks Brooks. A blue bus passes a girl in a yellow raincoat. The light turns red. Now the steam is coming out of the manhole on 42nd Street.

Travis almost runs into Iris the young sex worker as she’s crossing the street. It’s late. A girl her age should be home in bed. Travis is in his yellow cab. Iris is in her big hat and white bellbottoms. Paul Pelosi was home in bed. Iris is stoned, in over her head. Travis is wired on no sleep and junk food. He carries a gun. Pelosi wrestled for control of a hammer. “Let me ask you something, Travis, what is the one thing about this country that bugs you the most?”

‘Marty is the greatest film teacher in the world’

Francis Ford Coppola

I met Scorsese many years ago. It was immediately like finding my long-lost cousin, an Italian-American like myself but one really of the same style: the same smells in the kitchen, the same wonderful parents and the same sense of being both American and Italian.

I loved the first film I saw of his, Who’s That Knocking at My Door?. But I also loved every one of his films in succession, as I saw them as he made them.

Marty is the greatest film teacher in the world. He certainly joins the ring of the greatest living film-makers working today – perhaps along with two or three others. I wish him a most happy birthday and a wonderful decade.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion