A Francis Ford Coppola Ranking

On cinema’s most underrated renegade.

Having now seen all of the films from Francis Ford Coppola that were at least somewhat appealing (Hell, I watched Jack, so I think I’ve earned a free pass on films like Finian’s Rainbow!), I figured that it was time that I gave his films a ranking and took a brief look back at each one. We’ll be going backwards, starting with the weakest, and from there it’ll all be upwards! Here are most of the films from one of America’s finest directors of all time put together in a personal order based on favouritism! I won’t be including New York Stories, as it’s more of a short film as opposed to a feature, but I will say that Coppola’s part of it is really quite bad. Scorsese certainly holds the project together. I also won’t be including The Godfather Epic, which is a supercut of the first two Godfather films into a single work, but I will say that that one is certainly worth seeing. This may serve as something of a blueprint to a larger Coppola retrospective somewhere down the line, too. He’s one of the all time greats, and a real renegade of the form.

18. Jack (1996)

Let’s be honest, Jack is pretty terrible. Not that anybody says it isn’t — I don’t think I’ve seen anybody ever try to defend this movie beyond a quietly murmured admittance of nostalgic bias — but considering that it comes from a director as good as Coppola, it always surprises me when I remember that at one point he stooped to this level. Not even Robin Williams can save it, and that’s really saying something. I guess, if you want to see a scene wherein Bill Cosby farts so hard he makes a treehouse full of children fall down, this is the movie for you, but other than that, avoid this at all costs. It’s just terrible, even for a kids movie, but at least it led to the break that spawned some of Coppola’s finest work upon returning.

17. The Godfather Part III (1990)

Whilst it’s not entirely bad, The Godfather Part III seems to meagrely limp through its plot and stumble through its dramatic sequences. It’s a shame that the series fizzled out as hard as it did, considering the intense strength of the first film, but it’s forgivable considering that this was made almost twenty years after the first, during Coppola’s one creative slump.

It may not be entirely fair to rank this one as low as this considering that I haven’t seen the recently re-released cut (titled the Encore cut), but similar to the third Godfather film, this one just feels a little limp in comparison to the heights of Coppola’s direction. It’s not bad, but little about it stands out aside from Richard Gere’s brilliant main performance and the costume design.

15. Twixt (2011)

As said earlier, I think that when Coppola came back from his post-Jack break from directing, he made some of his finest work… with Twixt as the exception. Twixt does get some bonus points just for trying, a total A+ for effort if ever there was, and almost does get by just for having the balls and the confidence to try some of the things it does — being a weird, gothic horror comedy… thing(?) has its merits, and it means that a lot of the weirder parts here that don’t quite work get a free pass, but still, the film doesn’t come together anywhere near as much as the other 21st century Coppola films.

One of Coppola’s earliest works, The Rain People is a lean and mostly quite straight forward domestic melodrama. It has good performances, the type of storyline and editing typical of the Movie Brats clique at the time (see also Boxcar Bertha and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore by Scorsese, for example), but it never goes beyond that, and settles to be solid.

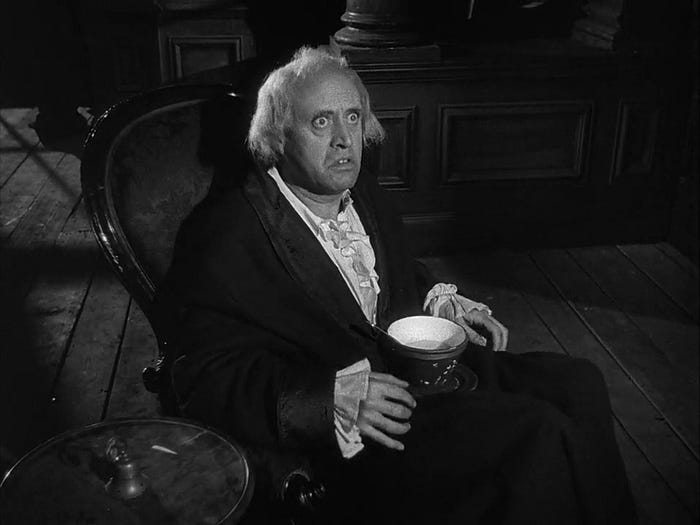

13. Dracula (1992)

Similarly to Twixt, Dracula elevates itself somewhat just by being utterly bizarre. This film is stronger than Twixt, but it certainly has its fair share of silliness and flaws, taking the source to new and certainly odd places, from Keanu Reeves’ dodgy accent to Gary Oldman’s look, but it dares to go so deeply into the exaggerated gothic look that it becomes entertaining, almost in spite of itself. It’s a shame that this is the extravagant and over the top Coppola film that caught on, as opposed to his films like Youth Without Youth and One From The Heart (especially the latter).

12. Peggy Sue Got Married (1986)

This is where the movies really start to get great. Peggy Sue Got Married is a film that doesn’t feel like it should be anywhere near as good as it actually is, but thanks to Coppola’s cautious blending of nostalgia, great performances and some cinematic fads at the time such as time travel, high school comedy/dramas and nostalgia for the 50s in particular, this film does do a wonderful job at filling the shoes of a film like George Lucas’ American Graffiti (no doubt a great double bill if you were to put the two together!). It’s an easygoing watch, and even features a young Nicolas Cage, so it’s certainly worth watching.

11. Tetro (2009)

The second film after Coppola’s long awaited return to cinema (he made nothing from 1997 until 2007, taking a decade away from cinema, presumably to re-coup after a string of successive ‘failures’, some of which I quite like), Tetro is something that feels deeply connected to Youth Without Youth, the other film made since Coppola’s return, but deeply disconnected from everything else that he had made up to this point. Using monochrome in a Buenos Aires setting, the film focuses on Tetro, played by Vincent Gallo, who has left home in an attempt to reinvent himself (sounds a little familiar, don’t you think?) and escape his past. Whilst Youth Without Youth was a little too disjointed and fragmented to capture the attention of many critics — the only reason that the film seemed catch on even slightly was because Coppola’s name with attached, or at least it certainly seemed that way — Tetro managed to bring some attention to itself by focusing plenty of attention on stylistic traits which come together beautifully and complement the deeply heartfelt story which is further fuelled by the excellent performances at the centre.

Rumble Fish is most likely the most well known film that Coppola made during his frantic 80s period, in which he directed five films between 1982 and 1986, all of them receiving some praise but nowhere near as much as Coppola’s undefeated 70s streak. Following up on Coppola’s previous film, The Outsiders, that had been released the same year and featured much of the same cast, both sharing a similar focus on rebellious teenaged gangs and their struggles with time and ideas of getting older becoming increasingly unavoidable,Rumble Fish had some big shoes to fill but it manages it effortlessly. An intelligent, delicately crafted film that really shows Coppola’s emotional strength in communication, and proves that he was right to deviate from his prestige dramas of the 1970s.

Coppola made just one more film following the disaster that is Jack before he took his decade long break, and that film happened to be The Rainmaker, a John Grisham adaptation focused on a battle between a scummy lawyer and a… slightly less scummy lawyer made likeable by the plot! Matt Damon and Danny DeVito are the less scummy lawyers, with Damon acting as the typical fish out of water turned stone cold smart aleck genius and DeVito as his lazy and washed up mentor. What I’m saying is that, if you’re a sucker for courtroom dramas as much as I am, this film is a damn goldmine, even if it follows up on just about every single cliche of the genre. It’s one of those films that doesn’t feel like it’s silly as it goes down the courtroom drama tropes list and ticks practically every single box along the way, with the cast and the franticness of the direction elevating the film above the pitfalls of its genre somewhat. It’s a film that many seem to have forgotten about, and I certainly don’t think that it earned its reputation as just another courtroom drama considering the thrills it delivers consistently. A wonderful example of a film from one of my personal favourite genres.

Youth Without Youth is the film what Coppola made his grand return with, and it certainly marked a massive change in his cinematic approach. It is almost ironic that his films started off taking so much from the Hollywood New Wave and his 70s films were so clearly American as their roots for Coppola to return after a decade’s break with a film that feels so intrinsically like something taken straight out of a European arthouse theatre. Using a disorienting story, a dazzling range of colours, a focus on metaphysics and superpowers (yes, you’re reading that correctly) as they work against his more American sensibilities as a director, Coppola creates a film that seems to be at odds with itself, with two very different styles fighting for the most attention at the front of the film whilst the story and the context take something of a back seat to it, losing some of their prominence. Youth Without Youth isn’t a perfect film, but it is one of the most exciting, most out of left field and most bewildering film to come from a mainstream American director in a long time, next to works like Domino by Tony Scott, for example. It’s just a breath taker, and one that will impress most anybody I think.

Made the very same year as Coppola’s much more successful The Godfather Part II (I think that this one would have received even more praise had the release times not been so close together, but hey, what can you do?), The Conversation is a brilliant paranoid thriller following Harry Caul who overheard a conversation whilst doing surveillance work and becomes obsessed with what he infers as extreme danger, whilst everybody else brushes off what he hears. This film has a clearly large influence on the thrillers of the 70s in America that would follow, as it takes some sensibilities from film noir and incorporates them into something more modern (maybe an early example of neo-noir here, though I’m not sure I’d go as far as to call it that outright — food for thought, nonetheless), and thus inspires the style of the De Palma thrillers that would come out around the same time — say that you will about the Hitchcock influence, that one is plenty clear on both De Palma and The Conversation, but not many people give this film much credit in inspiring De Palma’s very deliberate ebb-and-flow pacing that he used many, many times in his earlier career… just look at Obsession (1976)! The film is made as good as it is thanks largely to the cinematography, which crawls around the cityscapes and the claustrophobia inducing apartments and edges in on Gene Hackman’s sweat covered face, ushering in a tense atmosphere that feels simultaneously delicate and almost empty. One of the finest thrillers of the 1970s, one that would go on to inspire many other brilliant films like the already mentioned Obsession (De Palma, 1976) and Rolling Thunder (John Flynn, 1977) — both notably written by Paul Schrader. Influence begets influence, I suppose.

6. The Godfather Part II (1974)

I may get some flack for placing this as low as sixth, but I do adore this film. I had always underrated it, I admit, but having recently rewatched it I was finally able to bask in the delicious complexity of its storyline and to fall for its phenomenal use of cross-cutting between the adventures of Robert De Niro’s Vito Corleone and Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone. It’s a masterfully controlled film, and one that I honestly imagine will continue to grow on me over time, but for now it sits here.

5. Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988)

I actually had rather low expectations before going into this film, and I’m not entirely sure why considering that I’ve said for a long time that 80s Coppola is my favourite era of his filmmaking. Tucker certainly follows the trademarks of his 80s work too, it’s a film that backs up a little on the form to make space for something more surreal that adds more to the emotional standpoint of the characters, which I don’t often prefer to realism, but for some reason, it really works for me in this case. The film makes use of leading lines, wide lenses, endless crane shots that tower above the characters all with the purpose of making us see the world from Tucker’s larger than life perspective. The cinematography is also definitely inspired by the noir films from the time in which the film is set (post war 40s — early 50s), even if the vibrant score would have you think otherwise.

Coppola doubles down on his 50s nostalgia as he studies the story of Preston Tucker, an intensely innovative car designer who is hindered consistently by those with more power and money than him, trying to ruin his dream. The focus on a man trying to create something new and being stopped by those with more power and/or finances must link to Coppola’s personal life as a filmmaker, as his financial troubles with budgeting ran awry a few times and it’s not difficult to imagine that Coppola was forced to shelve plenty of projects due to budgetary concerns from producers and financiers. Given that George Lucas also produce the film, it makes sense that this tells a lot of his story too, as his own financial troubles in making Star Wars, which turned out to completely defy expectations and become one of the most culturally popular films of all time even after almost fifty years, could have easily led to the project being scrapped were it not for Lucas’ determination to complete it — something Tucker also shares. Coppola also morphs this focus on innovation of technology into his form, consistently using hidden cuts, shots that move between sets seamlessly (this technique works wonders during the phone call sequences) and the aforementioned crane shots, creating this impossibly clean look with hazy orange lighting reminiscent of something out of a dream.

That’s not the only way that the film is personal though. The focus on family and on the failure of the American Dream (the dreamy orange look makes even more sense now!) also bring to life Coppola’s views as well as Tucker’s. The portrayal of the American Dream as something that is ultimately robbed by those who have already ‘accomplished it’ (in a way) is brilliant, and the way that Coppola frames the story to show that genuine visions are so often perverted by the power of others is brilliant. This one is maybe the real dark horse of Coppola’s filmography, a film that slips by unannounced for so many but one that is really brilliant.

Of course, this one would be near the top of the list. It’s just legendary. The performances, the cinematography, the editing, even the lighting is so precise and well controlled here that it’s hard to believe. Not a lot to say, everybody has said everything there is to say about this film and its brilliance a million times over already, but they’re not wrong, it really is miraculous.

It may be surprising, but The Outsiders proves itself as one of Coppola’s most emotional films very quickly. Coming out just a year after One from the Heart, one of Coppola’s finest works and the one that set him apart from all of his much more serious and grounded earlier work from the 1970s (you know the ones!), The Outsiders was faced with the difficult challenge of having to stick to the same new ideals set up in Coppola’s previous film, whilst also having to perform well at the box office considering that One From the Heart didn’t live to its box office expectations. It was a make or break moment for Coppola, and one that he rose to the occasion of, creating one of the strongest coming of age films of all time. This is largely thanks to the terrific ensemble cast, which features younger versions of a lot of terrific stars, from Matt Dillon to Tom Cruise to Patrick Swayze, who all come together beautifully to tell the story of teenage angst gone awry in the most beautiful way. It’s something of a nostalgia fest, but it does so well with what it has that it’s completely forgivable in being such a thing. A really wonderful film, and it embodies exactly the type of coming of age film that people are trying their hardest to make now but almost always just missing the mark. It’s a great adaptation of a great book, turned to a deeply moving melodrama that takes from the 50s and 60s whilst updating these stories with Coppola’s technical abilities.

I know it’s quite likely that I’ll get into some trouble for placing this above a film as esteemed as The Godfather, but One from the Heart serves to show Coppola’s real interests within cinema. Considered to be his first real passion project by many (I’d argue that Apocalypse Now is, considering the lengths he went to to complete it, but… I suppose I don’t get the final say in this case), this film simply oozes cool from start to finish. Helped along massively by Tom Waits’ excellent soundtrack produced solely for the film, the performances (especially from Nastassja Kinski!), the set design and the cinematography that captures it all, One from the Heart is simply put one of the smoothest films ever made, and it marked Coppola removing his shackles entirely.

Ending with the cacophonous, chaotic Apocalypse Now feels quite suitable. Given the film’s insane behind the scenes story, the intensity of the performances, the ridiculous power within the editing, the epic cinematography, the iconic use of colour, the firecracker dialogue, the brilliant adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s story Heart of Darkness, which follows a man’s descent into madness that is updated by Coppola to function as a comment against the Vietnam War that studies the psychological impact of what was ultimately a pointless battle has to be his finest work (to date, anyway — who knows what might come next?). I personally prefer the Redux version, just for the opportunity to spend another forty minutes or so with the characters and within this uncompromising world that becomes progressively more unhinged and hallucinatory as the film hurtles towards its unforgettable finale. This film is absolutely second to none in terms of Coppola’s work, and there aren’t many films in general that rival it. But you already know that.

Additional Note: I do want to acknowledge that there are two new cuts from Coppola which I am yet to see — I haven’t been able to see Coppola’s new cut for The Godfather Part III (The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone) or The Cotton Club (The Cotton Club Encore), so that may explain their lower positions as I imagine that the new cuts have more to offer.

For more from me on film, see the list below:

Alternatively, if you want to support my writing, you can donate using Ko-fi.