At the end of the summer in 2017 I lost myself under a motherload of wifedom: organising separate new schools for my teenage daughters, my son’s holiday programme (bring extra shirt for tie-dye!), ferrying a depressed French exchange student to see the sights, arranging for recalcitrant tradesmen to patch up my old house, sorting out a relative’s hospital care, and hosting dear family at a time of great sadness. As I shopped for groceries, yet again, in the local mall, writing deadlines ticked. When the exit machine inhaled my ticket, I knew: something had sucked out my privileged, perimenopausal soul. I had to get her back.

There are doubtless more practical ways to handle a crisis, but I turned to George Orwell’s famous essay, Why I Write. “I knew,” Orwell says, “that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life.” I would read him, I thought, to help me face some unpleasant facts about the division of labour in my household. In exploring the tyrannies, the “smelly little orthodoxies” of his time, I hoped to liberate myself from mine.

I read my way through his work – so funny, so acute. And then as summer shifted into autumn I read the six major biographies of Orwell, by Peter Stansky and William Abrahams (1972), Bernard Crick (1980), Michael Shelden (1991), Jeffrey Meyers (2001), DJ Taylor and Gordon Bowker (both 2003).

When I’d finished them I came across six letters from Orwell’s brilliant, whimsical wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy, to her best friend Norah Symes Myles, with whom she read English at Oxford in the early 1920s. Discovered in 2005, after all the biographies were written, their correspondence dates from the beginning of the Orwell marriage, through the Spanish civil war, the couple’s time in Morocco, and into wartime London during the blitz. The letters are a revelation. More than half a century after his death, a door to Orwell’s private life has been opened, revealing the woman who lived behind it – and the man who wrote there – in a whole new light.

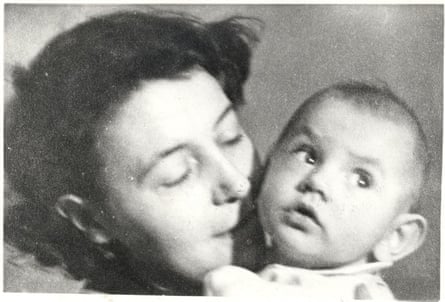

Eileen was born in 1905 in South Shields, where her father worked in customs. Her family was better off and better placed than Orwell’s (which he famously described as “lower upper middle class”). Eileen was head girl and a stellar student, winning a scholarship to read English at St Hugh’s, where JRR Tolkien was one of her tutors. She was disappointed to get a high second-class degree, rather than a first.

After graduating she took on a range of jobs, including in secretarial offices (at one of which she led a successful revolt against a bullying boss), and wrote feature journalism and poetry, including a poem called End of the Century, 1984, projecting a future of telepathy and mind control. At the time she met Orwell, she was undertaking a master’s in psychology at UCL.

In the first letter, dated November 1936, nearly six months after the wedding, Eileen tries to explain why she couldn’t write sooner:

I wrote the address quite a long time ago & have since played with three cats, made a cigarette… poked the fire & driven Eric [ie George] nearly mad – all because I didn’t really know what to say. I lost my habit of punctual correspondence during the first few weeks of marriage because we quarrelled so continuously & really bitterly that I thought I’d save time & just write one letter to everyone when the murder or separation had been accomplished.

Static buzzed through me. What are the arguments about, in these early days of marriage? Why does she want to kill him, even in jest? And why, having just devoured the six brilliant biographies, did I barely know who she was?

I went back to the biographers to find out. The newlyweds were living in a tiny cottage in Wallington, 30 miles from London, with no electricity, one tap and an outdoor privy. According to some of them, he’s “the happiest he’s ever been… Indeed, only in that summer of 1936 would there be such a combination of elements and circumstances as to fulfil an ideal of happiness for him.”

Orwell’s “combination of elements and circumstances” are, apparently, happy accidents rather than a situation tailor-made for him by Eileen. These conditions appear to exist without a creator, because the passive voice has made her disappear.

For mysterious reasons the biographers don’t directly attribute to Eileen, his writing suddenly got much better. ‘‘It is likely that the transformation in Orwell’s work from Wigan Pier onwards owes a great deal to the intellectual stimulus his marriage brought him,” one writes, by way of eliding understatement. Eileen had taken the word “obey” out of her marriage vows: the first radical act of the editing genius – she wrote “emendations” on his drafts, and they worked very closely together on Animal Farm – that would define her marriage.

But Eileen was there, working, dealing with his correspondence, organising their social lives, doing all the shopping (involving a bus ride to a village three miles away) and much of the cleaning (there is, intermittently, a “char”), tackling the occasional flood, the cesspit, the house, the garden, his illnesses, the chickens, the goat and the visitors. And managing her impulses towards murder or separation when George doesn’t want his work interrupted by life. (He “complained bitterly when we’d been married a week that he’d only done two good days’ work out of seven,” Eileen wrote to Norah.)

But how was it then, for her? Biographers, including Eileen’s biographer Sylvia Topp in her 2020 crowdfunded work Eileen: The Making of George Orwell, imply Eileen’s willing consent to the sudden helpmeet role she found herself in. Comments in the Orwell biographies such as Eileen “even helped clean out the latrine” made it appear like her newlywed enthusiasm extended to helping George clean out the privy. But the truth is she did it alone, and remembered it all her life.

On top of the housework, Orwell’s needs keep her from visiting Norah:

I thought I could come & see you & have twice decided when I could, but Eric always gets something if I’m going away if he has notice of the fact, & if he has no notice (when Eric my brother arrives & removes me as he has done twice) he gets something when I’ve gone so that I have to come home again.

No one knows precisely when Orwell contracted the TB that killed him in 1950, but he’d had poor lungs all his life, and the haemorrhages began early in their marriage. From the very beginning, Eileen saw how he’d use them.

I kept reading. Then, as winter set in, I came across something Orwell wrote during his final illness. In his private literary notebook, he wrote in the third person, as if to distance himself from feelings that were hard to own.

There were two great facts about women which… you could only learn by getting married, & which flatly contradicted the picture of themselves that women had managed to impose upon the world. One was their incorrigible dirtiness & untidiness. The other was their terrible, devouring sexuality… he suspected that in every marriage the struggle was always the same – the man trying to escape from sexual intercourse, to do it only when he felt like it (or with other women), the woman demanding it more & more, & more & more consciously despising her husband for his lack of virility.

Orwell only ever lived with one wife. These comments refer to Eileen. Orwell’s thoughts are painful to read. He’s paranoid, feeling he’s been tricked by a politico-sexual conspiracy of filthy women “imposing” a false “picture of themselves” on the world. He sees women – as wives – in terms of what they do for him, or “demand” of him. Not enough cleaning; too much sex. But how did she feel? My first guess: too much cleaning and not enough, or not good enough, sex.

For a long time, I felt queasy about delving into their intimate life. It felt like an invasion of privacy that he would have hated – anyone would. But history has relegated Eileen to the private realm where she lived – and has remained. The more I felt I was invading his privacy by looking for her, the more I realised that to not go there would be to accept, when weighing up the right to privacy against the right to decent treatment, that male animals are more equal than others.

I went back to the biographers’ footnotes and sources and into the archives and found details that had been left out. Eileen began to come to life. A colleague in a political office considered her “a superior person” compared with everyone else there – a detail quoted by no biographer. She was “diffident and unassuming in manner”, another co-worker and friend said, but “had a quiet integrity that I never saw shaken”. I discovered a woman who saw things and said things no one else did. Eileen loved Orwell “deeply, but with a tender amusement”. She noted his extraordinary political simplicity – which seems to have worried one of the biographers, who rewrote her words to give him an “extraordinary political sympathy” instead. And she objected to him being called “Saint George” on the grounds of his wizened, Christlike face. It was merely due, she said, to him having one or two teeth missing.

Eventually, as the evidence on the cutting room floor piled up around me, the biographies seemed to be fictions of omission.

Eileen made me laugh. Looking for her involved the pleasure of reading Orwell on how power works. Finding her held the possibility of revealing how it works on women.

How is a woman made to disappear? One of the more flamboyantly inventive instances of Orwell’s erasure of women comes from Down and Out in Paris and London. He recounts being robbed of all he possessed in his lodgings by a “swarthy Italian with side-whiskers”. But the truth was that he was robbed by a woman, a “little trollop” he adored, who he’d picked up in a Parisian cafe and installed in his hotel room. Suzanne, a streetwalker and con artist, was the woman he “loved best” of all the girls he’d known before Eileen. “She was beautiful, and had a figure like a boy, an Eton crop and [was] in every way desirable.” But Suzanne can’t be given the power to con him because that would reduce, and therefore, shame him.

A more monumental disappearing trick happens in Homage to Catalonia – one of my favourite books since my teens. You can read it again and again and barely register that Orwell was not in Spain alone – Eileen was there too, almost the whole time. You would never know from Orwell’s book, nor the biographers’ accounts, that she worked in the headquarters of the political party Orwell was fighting for while he was off in the trenches with his fellow infantrymen.

The whole time he was fighting, she was working on print and radio propaganda for the party, provisioning the men, dealing with communications, arranging the transport of medical supplies from London, lending money of her own when the party leader had none, and dodging Stalinist spies in the office and in the hotel where she lived. When she visited Orwell on the battlefield, they came under fire. He was shot, but she cared for him and saved his manuscript (which she’d been typing) and then, during a two-hour-long Stalinist raid on their room, she stayed in bed to conceal the passports and chequebook she’d hidden under the mattress, allowing them to escape. (Orwell does tell that story, though for him it’s not about his wife, but is rather a demonstration of the “decency” of the Spanish men – even when under Stalinist control – in not turfing a woman out of bed.)

In the end, Eileen got them both out of Spain by fronting up to the same police prefecture those men had probably been sent from, to get the visas they needed to leave. One biographer eliminates her with the passive voice, writing: “By now, thanks to the British consulate, their passports were in order.” In Homage, Orwell mentions “my wife” 37 times but never once names her. No character can come to life without a name. But from a wife, which is a job description, all can be stolen. I wondered what she felt as she typed those pages.

Stalin, though, could see her perfectly clearly. As they fled Spain, his operatives issued an arrest warrant from the Tribunal of Espionage & High Treason, in the names of “Eric Blair and his wife, Eileen Blair… Their correspondence reveals that they are rabid Trotskyites”.

As I came to recognise the methods of omission, they fascinated me. When women can’t be left out, they are doubted, trivialised, or reduced to footnotes in eight-point type. Other times, chronology is manipulated to conceal. But the most insidious way the actions of women are omitted is by using the passive voice.

Manuscripts are typed without typists, idyllic circumstances exist without creators, an escape from Stalinist pursuers is achieved, by the passports being “in order”. Every time I saw “it was arranged that” or “nobody was hurt” I became sensitised – who arranged it? Who might have been hurt?

I didn’t want to take Orwell, or his work, down in any way. I worried he might risk being “cancelled” by the story I’m telling. Though she, of course, has been cancelled already – by patriarchy. I needed to find a way to hold them all – work, man and wife – in a constellation in my mind, each part keeping the other in place. I was fortunate to obtain permission to use the six letters from Eileen to Norah, and from them I created a counterfiction, to exist alongside the fiction of omission in the biographies.

We think we’ve come a long way in 80 years, but statistically, there is an irrefutable, globally intransigent heterosexual norm that pervades across ethnicity, colour and class. Nowhere in the world do women have the same power, freedom, leisure or money as their male partners. Every society is built on the unpaid or underpaid work of women, an estimated $10.9tn (£8.5tn) of it a year. But to pay would be to redistribute wealth and power in a way that might defund and defang patriarchy.

Things in the rear-view mirror are closer than they appear.

Which reminds me, of course, of my own, unseen, unsung conditions of production. As my husband says, with a wry smile: “You couldn’t have written this book without me.” And he’s absolutely right.

Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder is published on 17 August by Viking (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion