Tuesday, 18 July 1922. In spite of the rain, by breakfast, 600 people had gathered outside St. Margaret’s, the 12th-century church in the shadow of Westminster Abbey and a favorite for society weddings. By lunchtime the crowd would swell to 8,000. For the Daily Telegraph, this was to be the Wedding of the Year—the Star thought it the Wedding of the Century— between the beautiful Edwina Ashley, "the richest girl in the world," and Lord Louis Mountbatten, the handsome naval officer and member of the extended Royal Family. King George V and Queen Mary and most members of the Royal Family were attending, with the Prince of Wales as best man.

At exactly 2.15 p.m., Edwina entered the church to Wagner’s Lohengrin. The service was conducted by Dickie’s former school tutor, Frederic Lawrence Long. "The Lord is My Shepherd" was followed by the hymns "Thine for Ever" and "May the Grace of God our Savior," whilst Beethoven’s "Hallelujah" was sung during the signing of the register.

The couple—Dickie at six foot two dwarfing his wife—emerged from the church to Mendelssohn’s "Wedding March" just as the sun broke through the rain and they walked under the traditional arch of swords of a naval guard of honor. Mountbatten, his sharp chiseled face set in a solemn expression, was dressed in a long, blue frock coat and golden epaulettes in the dress uniform of a naval lieutenant and carrying his father’s gold-hilted sword. Edwina, blue-eyed and fair-haired, was in a simple, ankle-length frosted silver dress, with a wreath of orange blossom on her head, and a four-foot train of silver cloth covered with 15th-century lace.

They climbed into the bridal car, a Rolls-Royce—a wedding gift from Edwina bought from the Prince of Wales—which was then drawn by a naval gun crew around Parliament Square. Around the corner, a flag-draped lorry took over, towing the car past Buckingham Palace to the reception at the bride’s home, Brook House in Park Lane. There, at the entrance to the two ground floor reception rooms, where a narrow dividing room had been made into an avenue of 10-foot orange trees, the couple received their 800 guests. So large was the wedding cake, with its top tier shaped like a crown, plus miniature anchors, sails and hawsers, and tiny lifeboats hanging from silver davits, that it took four men to lift it.

The wedding had attracted attention around the world with entire issues of magazines devoted to it, postcards and souvenirs produced to commemorate the occasion, and a 14-minute film for Pathé News. The list of presents took up a whole page of The Times and included, for Edwina, a pendant with the royal cipher in diamonds from Queen Alexandra, a brooch from the Aga Khan, a horse from the Maharajah of Jaipur, and the bracelet she had only recently returned to a previous suitor, Geordie, Duke of Sutherland. Mountbatten’s gifts were of a more practical bent, reflecting his interests—a ship’s telescope, a copper hot-water jug and an aneroid barometer—and from the King, the award Knight Commander Victorian Order to add to his cherished Japanese Order of the Rising Sun and Grand Cross Order of the Nile. Finally, at 5 p.m., they set off in the Rolls-Royce for the bride’s family home, Broadlands, to begin their married life together.

The marriage had brought together two of the most glamorous figures of the period. Dickie Mountbatten, born on 25 June 1900 at Frogmore House, was a great grandson and godson of Queen Victoria—his mother, Victoria, born in 1863, was the daughter of the Queen’s second daughter, Alice. Dickie’s mother was to be an important influence, encouraging in her youngest child supreme self-confidence and acting as his tutor between the ages of five and nine. "She taught me English, German, French and Latin. She taught me world history in a horizontal manner," he later recalled. "In the Elizabethan era, I knew what was going on in Europe and India as well as in England." He was christened Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas—the Victor and Albert in tribute to his great-grandparents—though from an early age he was always known as Dicky or Dickie.

His father, Prince Louis, born in 1854 in Austria, was the son of Prince Alexander and Princess Julie of Hesse, the oldest ruling Protestant dynasty in the world, but, as it was a morganatic marriage, the children were excluded from the succession to the sovereignty of Hesse. This genealogical flaw in Mountbatten’s ascendance was to be an embarrassment, which he would seek to brush over in later life.

Dickie’s father had joined the Royal Navy, aged 14, and enjoyed a successful naval career, becoming Director of Naval Intelligence shortly after his younger son’s birth. Part of the slightly louche set around Edward VII—his torso boasted a tattoo of a dragon—in 1881 he had fathered a child, Jeanne Marie, with the King’s mistress, Lillie Langtry.

In 1884, Prince Louis had married his cousin, Victoria, eldest daughter of Grand Duke Louis of Hesse and a favorite granddaughter of Queen Victoria, and their children, Alice, Louise and George, were born respectively in 1885, 1889 and 1892. Fluent in French and German, a skilled pianist and artist, who had been elected to the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours, he was worshipped by his youngest child.

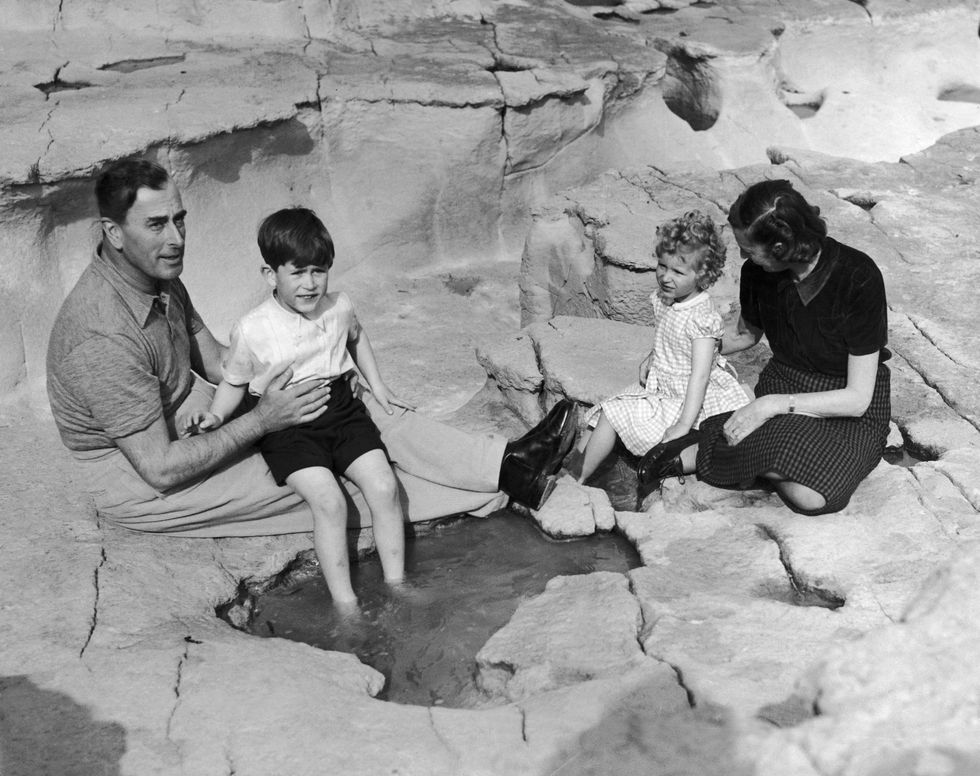

As the youngest and with a gap of between 15 and eight years with his siblings, Dickie was used to amusing himself and getting his own way. He later recollected, "I was spoilt and no one minded." His was an essentially female household, as his brother and father were seldom at home, where he was doted on by his mother, two elder sisters and various female members of staff. This was to have a powerful effect on him in later life. He was always to get on with women better than men, who were either to be admired, like his father and brother, or seen as antagonists to be defeated.

After finishing at Osborne, the Navy’s training school on the Isle of Wight, Dickie spent the summer of 1913 was spent in Hesse with his older siblings—Alice, now married to Prince Andrew of Greece, Louise and George, now a lieutenant serving in the battle cruiser HMS New Zealand. They were joined in Hesse by the Tsar and Tsarina and their five children, with one of whom, 14-year-old Marie, Dickie fell in love. "I was crackers about Marie, and was determined to marry her," he remembered. "She was absolutely lovely. I keep her photograph on the mantelpiece in my bedroom—always have." Within five years, all the family would be dead at the hands of the Bolsheviks.

On 28 June 1914, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo and the countdown to war began. Prince Louis had become First Sea Lord in 1912 and Dickie was invited to watch a full test mobilization of the Fleet on 18 July. Dickie was thrilled to watch the Royal Review at Spithead in front of King George V, with the full might of the Royal Navy laid out in front—and to meet Admiral Jellicoe and Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty.

Dickie had met Churchill several times before, not least when he had paid an official visit to Osborne. When Churchill had asked the cadets if they had any requests, Dickie had been the first to respond. "Please, sir, may we please have three sardines for Saturday supper instead of only two?" "I’ll see to that," Churchill assured him. The sardines were never forthcoming. It was a lesson that Dickie was to remember.

It was Prince Louis, alone on duty, on the fateful Friday before the outbreak of war, who had to make the decision not to stand down the Fleet, but keep them mobilized. It proved to be a wise decision. The following day, Germany and Russia declared war on each other and on 4 August, the United Kingdom declared war on Germany.

There was an almost instant wave of anti-German feeling, with assaults on suspected Germans—even dachshunds were targeted—and the looting of stores owned by people with German-sounding names.

In October, the German-accented Prince Louis, feeling that the criticisms of him as head of the Navy were a distraction from the war effort, resigned as First Sea Lord. He had faithfully served his adopted country for 46 years and yet Winston Churchill made no attempt to dissuade him. His son was devastated. Another cadet saw a contemporary standing in front of the Osborne mast with tears running down his cheeks. It was Dickie. From that day he was to have one consuming ambition, to avenge his father’s dismissal and become First Sea Lord himself.

A descendant of the Native American princess Pocahontas, the Prime Minister Lord Palmerston and the reformer and philanthropist the seventh Earl of Shaftsbury, Edwina was born on 28 November 1901. Her father, Wilfrid Ashley, was a former colonel in the Grenadier Guards, who would later become a Conservative Member of Parliament. Her maternal grandfather was the banker, Sir Ernest Cassel, financial adviser to Edward VII—the King was Edwina’s godfather and she was named after him—and one of the richest men in the world.

Cassel, whose wife had died within three years of marriage, was very close to his only child and her first-born daughter and provided one of the few anchors in Edwina’s rather rootless youth. Edwina’s father was a remote figure, busy pursuing his parliamentary business or sporting interests, and her mother, Maud, frequently ill, had no idea how to be a parent to Edwina.

Maud died of tuberculosis in February 1911, when Edwina was nine and her sister Mary was five. Neither child was allowed to attend the funeral at Romsey Abbey. Edwina wrote to her father, "I am so very sorry darling Mama left us all so suddenly and for ever, I wanted to kiss her once and now I didn’t, but it is very nice to think her spirit will always be with me." She never spoke of her mother again in public.

Both daughters found it hard to come to terms with their mother’s death, but displayed it in different ways. Edwina was forced to grow up quickly, became ever neater and more dutiful, while Mary responded by becoming more willful and uncooperative. Motherless and starved of affection at home, Edwina poured her love into caring for her animals— puppies, ponies, rabbits, kittens, a goat and, a present from her grandfather, an Arab horse. Educated at home, she was a conscientious and organized student, who by the age of 10 could read German, write in French and play the piano. She had a particular love for geography, noted one biographer. "Maps fascinated her, talk of distant lands gripped her attention, and she would read travel books voraciously."

The anti-German hysteria that had affected the Battenbergs was now directed at the German-born Ernest Cassel. In spite of being one of the largest subscribers to the War Loan and entrusted with an official mission to the United States to secure a loan of half a million dollars, he was accused of being friendly with the German Emperor and having a specially designed wireless set on the roof of Brook House to maintain contact with the country of his birth. Sir George Makgill, Secretary to the Anti-German Union, brought a lawsuit to strip Cassel of his membership of the Privy Council. It failed, but for Edwina—like her future husband remembering his father’s experiences—it was something she would never forget.

Excerpted from The Mountbattens: The Lives and Loves of Dickie and Edwina Mountbatten by Andrew Lownie. Published by Pegasus Books. © Andrew Lownie. Reprinted with permission.