Obituary: Ed Koch

- Published

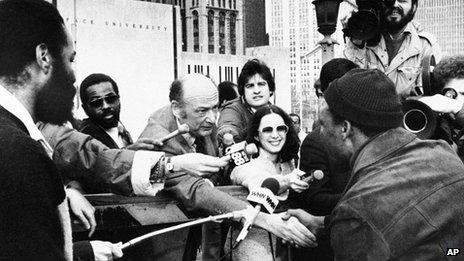

"How'm I doin'?"

Ed Koch, the ebullient, outspoken mayor of New York City, wanted to know.

That was his trademark greeting, as he met citizens and New York's boisterous press during his rollicking three terms in City Hall.

Koch, who died on Friday aged 88, shepherded the city through some of its darkest days.

In 1978, when he took office, the city was near broke, its buildings and subways scrawled with graffiti, its streets grimy and plagued with crime.

The city was not much nicer when he left office on 1 January 1990. But Koch has been credited with laying a fiscal foundation that enabled New York to become the clean, safe and prosperous world capital it is today.

Edward Irving Koch was born in 1924 in New York's Bronx borough, the son of Polish Jewish immigrants.

During the Great Depression, his family moved to Newark, New Jersey and later settled in Ocean Parkway, Brooklyn, when he was a teenager.

'Hard times'

After studying at City College, a famed state school, he was drafted into the US Army and became a decorated combat infantryman. He earned a law degree from New York University in 1948.

He entered local Democratic New York politics in the 1960s and was elected to Congress in 1968. In November 1977, he was elected mayor.

"These have been hard times," he told the city upon his inauguration.

"We have been drawn across the knife-edge of poverty. We have been shaken by troubles that would have destroyed any other city. But we are not any other city. We are the city of New York and New York in adversity towers above any other city in the world."

Upon taking office, Koch confronted a near-empty treasury, frayed relations between the city's black population and its government and police, an unwieldy patronage bureaucracy at City Hall, mass transit he agreed "stinks", and a restive population of more than seven million.

Famously combative with the press and his political opponents and passionate about the causes he backed, Koch was described in 1980 by New York Times writer Clyde Haberman as being "as self-absorbed as anyone who has ever run New York's City Hall".

Koch seemed to think nothing of thundering "dummies!" at a group of black voters in an audience who expressed a preference for a rival, nor of telling synagogue congregants who booed him to "shut up".

And he once walked out on an audience of more than 1,000 middle-class Irish and Italian Catholics in Queens because a priest said he could have one minute to address the critical crowd - but not two.

During his first term, the subway system remained miserable, the streets and parks remained squalid, and crime remained at record highs.

But Koch defied his critics to become one of the most popular politicians in the country. In early 1981, as he prepared to face the voters for re-election, his public approval rating was an enviable 62%.

'A future again'

He was credited with balancing the city's budget and enabling it to raise funds on the bond market. And despite the long, painful economic downturn of the late 1970s and early 1980s, Broadway was booming, retail sales grew, and restaurants were packed.

In September 1981, Koch made history by winning both the Democratic and Republican mayoral nominations. He was re-elected that November with an astonishing 75% of the vote.

"New Yorkers, you are the magnificent seven-and-a-half million, and because of you New York City has a future again," he said that night.

"I am grateful for the chance you have given me for another four years."

But with characteristic cheek, he added: "I cannot promise you that I will work any harder, because I've given the job all I've had."

In the mid-1980s the city finally cleared the subway system of graffiti and spent $19bn (£12bn) on capital investments. Wall Street boomed. Koch was re-elected again in 1985.

Koch vowed to become the first four-term mayor of New York. But by 1989, New Yorkers were ready for a change, soured perhaps by his constant scraps with other public officials and with the press, and turned off by a series of government corruption scandals.

Koch lost the 1989 Democratic primary election to Manhattan Borough President David Dinkins, who would go on to win election as New York's first black mayor.

Later, Koch remained extraordinarily popular among New Yorkers as the city thrived and prospered and once-run down neighbourhoods in Manhattan and Brooklyn gentrified and came to sparkle.

Koch never married - and throughout his life refused to address enduring speculation he was gay.

He practised law, wrote newspaper columns and hosted a radio chat show. In 2011, the city renamed the Queensboro Bridge - a crowded, cranky, 110-year-old span over the East River - for Koch.

His health began rapidly to fail over the past several years and he was in and out of hospital. At his 88th birthday party in December, he was warmly introduced by a host of New York dignitaries. Then he addressed the party himself.

"I wake up every morning," he said, "and I say, 'Oh, I'm still in New York!'"

- Published1 February 2013