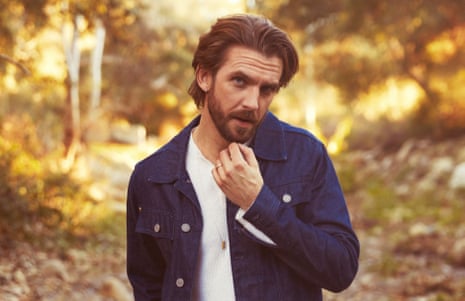

When I speak to Dan Stevens, he’s in Los Angeles, shooting Gaslit, a forthcoming TV show that sounds like the definitive deep dive into the Watergate scandal. It’s full of big hitters – Stevens and Betty Gilpin playing John and Mo Dean, Sean Penn and Julia Roberts as John and Martha Mitchell – and is based on the podcast Slow Burn, which is marvellous, if you get a minute and want a refresh on who these people are.

Ever since his years on Downton Abbey, Stevens, 38, has been very much in that glossy league, moving seamlessly between British period drama and high-rolling US sci-fi – he is the lead in Legion, Noah Hawley’s epic addition to the Marvel universe – with hybrid projects in between. Blithe Spirit, for example, a British reinvention of Noël Coward’s classic, with a sort of American reverence for the past, and a partly US cast. It wasn’t very well-reviewed, but that’s beside the point; this is an actor who makes sense in many contexts, for whom there is very high demand. That – although like everyone he says he has had “chunks of months here and there” without work – has been the story of his career since his first professional job, cast as Orlando by Peter Hall in As You Like It. Hall had spotted him in a university production of Macbeth.

We’re actually here to discuss I’m Your Man (Ich bin dein Mensch), a German romcom so subtle, deceptive and textured that it was days before I realised it was actually a romtraj. He plays robot boyfriend to Maren Eggert’s lonely human, balanced like an acrobat throughout between computer-impersonating-person and person wondering “what-does-person-mean-anyway?”. So obviously my first, incredibly parochial question is how on earth does he speak German? He learned it at school, had friends in Germany, visited regularly, loves Berlin. It’s not a classic polyglot’s trajectory, it sounds more like the way someone learns languages in an EM Forster novel. And he concedes: “I think the list is relatively small, you know, English actors who actually speak German.”

It sounds like a challenge, playing a robot – your proposition is to have no feelings, after all, and feelings are usually your one job. “Always,” he says, “when you’re doing an android story, it’s not really about the android, it’s not really about the technology, it’s about the human, and what the human desires; what we do with that technology or what that technology teaches us about ourselves.” And it is true that all the emotional focus is on Eggert, who won the Berlin film festival’s first ever gender-neutral acting prize (which is so Berlin) for the role. From Stevens’s point of view, it was quite a modest role to take on, since he is essentially a reflective space for Eggert.

Anyway, what was ultimately so tragic about the film – I don’t think it’s a spoiler if I give away the underlying philosophy – is its conclusion, that all romantic love is a projection, whether it’s with a robot or not. “Maybe …” he says, cautiously not agreeing. “Definitely, at the start of every romantic relationship, part of it evolves in very simple programming terms: ‘This is working, I’ll do more of this. Right, right, not working, I’ll try not to do that.’”

Certainly, taken together with Legion, I’m Your Man suggests a preference not necessarily for sci-fi but for romantic scenarios much more complicated than classic love stories. “I don’t know that I ever actively lost interest in romance, it’s just that, very often, romantic leads are not very well written. They’re not that interesting, the will-they, won’t-they stories.”

At university, before his performance opposite Hall’s daughter Rebecca put him on the professional stage, Stevens was much more interested in comedy. He was at Cambridge, in the Footlights, but he hasn’t got a very standup personality (as in, “built for standup comedy”, not “decent”). It was more about “character creations. I really admire Peter Sellers. You learn such a lot about stagecraft doing comedy.”

While it was in The Line of Beauty, in 2006, that Stevens got his small-screen break, naturally Downton Abbey, in which he was cast as Matthew Crawley in 2010, was more defining, if only because – in case you’ve forgotten, it was a decade ago and a lot has happened in between – we all used to talk about it so much. The show split the crowd. If you surrendered to its superb performances and sheer sumptuousness, it was Sunday-night TV at its finest. If you asked too many questions about its, and TV’s general, craven fascination with posh people, it might have made you feel a bit mournful.

Stevens gnomically bats away any suggestion that it made him a household name, even though it did – “Obviously in your own household, people know your name. I guess it’s up to other people to take that name into their household” – but he does remember that “it was one of the early shows that was popularly live-tweeted, and that was interesting and exciting, but also a bit distressing. Instead of the odd critic, writing about you in the Sunday papers, you had everyone coming out with really strong opinions about specific scenes or what she was wearing or what he was looking like.”

Julian Fellowes, the creator and writer, said at the time that Stevens had “a kind of niceness, sympathetic in a way that harks back to an earlier tradition: Jack Hawkins or Kenneth More or Gary Cooper or Cary Grant”. There is a self-effacing quality, to both that performance and his general manner as he elaborates on it. “I look at other performances and absorb them, whether it’s imitative or trying to absorb the modes of acting in my memory bank, I don’t know.” And he’s always keen to resituate Downton Abbey as part of period drama tradition – he tries to divert me on to the more recent Bridgerton (which isn’t completely successful, given that he wasn’t in it), concluding: “You know the bodice ripper never quite goes away, I don’t think it ever will.” You wouldn’t necessarily conclude that he wasn’t proud of Downton, rather that he finds it burdensome to dance in his own spotlight and thinks he deserves a statute of limitations. Which is probably fair.

Unusually, after some slightly bruising experiences on social media, Stevens is still pretty active on Twitter himself, and comes over much more like a commentator than a performer – very often signal-boosting causes and amplifying articles, particularly, recently, Black Lives Matter. “It is definitely worth putting a stake in the ground on things are important.” (Strong start.) “But that’s not to say that, if I don’t say anything on a particular issue, it doesn’t mean anything to me.” (Good point, this is a minefield.) “It could be just that I don’t know quite how to express it, maybe feel it’s not my place to. And, you know, it’s a personal choice at the end of the day, some people choose to say nothing and I think that’s OK too.” I realise, as this unfolds, why actors so often don’t say anything remotely political – that space between being an ally and being performative about it, between saying anything at all and not saying enough, between making your own choices and being seen implicitly to judge other people’s, is just vanishingly narrow.

There’s a bit more freedom to have an opinion on culture. In 2012, Stevens was asked to be a Booker prize judge, after a spirited response to the 2011 shortlist on Late Review. It’s actually quite a chunky time commitment, reading 145 books, especially since his character hadn’t even been brutally and slightly improbably killed off in Downton at this point (was the lorry driving too fast? Or was the Christmas special moving too slow?). “I was very much the guy off the telly in that room of heavyweight academics and people who’ve written massive books that would wedge open many, many heavy doors. I took on a bit too much, to be honest.”

At around the same time, he started contributing to the now-defunct online quarterly the Junket, collections of essays, memoir and poetry, writing short stories and that kind of luxurious observation-in-miniature that young people like (OK, he’s not that young now, but this was 10 years ago). He was raised in Wales and later Kent by his parents, two teachers, before going to Tonbridge boarding school. What you pick up in his writing is much less public-school show-offy-ness and much more teacherly introspection. He rattles off the traits that his parents encouraged, a bit absent-mindedly: “Reading and studying, independent thought, an interest in the arts.”

He describes his approach to acting in quite academic terms, piecing together how things work, genre by genre. “I’ll do some Shakespeare, then a Noël Coward, some sort of zany comedy, a grisly horror, bolt on these bits and pieces, absorbing and learning and growing. Early on, I wasn’t good at screen auditions, it took a while to click into place. There are certain kinds of TV shows, which are made a lot in the UK, that suit the British classical theatrical style, but that doesn’t necessarily translate into other kinds of screen performance. Storytelling with a flick of the eye is something you can learn but it can’t necessarily be taught.”

In that sense, he says, filming Legion was “a conservatory in itself, every single day on set was vastly different in that show. From one scene to the next, you could be in almost a totally different genre. There were some very sentimental, romantic scenes; horror, thriller elements, action. I’ve never seen a camera team so excited by what they were trying to achieve.” It wasn’t the realisation of a lifelong dream. “I wasn’t that interested in the Marvel universe,” he says. I didn’t know people were allowed to say that any more.

Covid locked down Broadway in 2020 just before Stevens was due to open in Hangmen, the Martin McDonagh play that premiered in the Royal Court, London, in 2015. He steps rather carefully over that disappointment, mindful that there are worse things that can happen in a pandemic than your play getting cancelled after 13 previews. “We still had a fantastic time rehearsing it and getting into the theatre.”

Shortly afterwards, with I’m Your Man in between, he started filming Gaslit, “finding America and American politics endlessly fascinating”. He has lived away from the UK, mostly in the US, with his wife, the jazz singer Susie Stevens, and three children, Willow, Aubrey and Eden, for the best part of a decade. It makes perfect sense professionally, but at the level of the citizen, he describes – without too much angst, you understand – a kind of exile. “If I try and say anything about American politics, people tell me to go home; if I say anything about British politics, they’re like: ‘You don’t even live here.’”

He found that particularly trying over Brexit, when “there were things I couldn’t hold back on, some of those parliamentary debates, and some of the behaviour of our parliamentarians during that time was utterly despicable. And there was very little I could do. There’s only so much you can do from afar.” I consider saying something emollient, along the lines of: “Cheer up, we didn’t manage to do anything from a-near, either”, but he’s quite a serious-minded person. One gets the impression he wouldn’t parse the difference between “light” and “silly”.

Still, we carry on about Brexit for a bit, and the perspective of geographical distance, but also the feeling of being an outsider, and he says: “You’re asking questions as if I somehow have this transcendent overall view of myself. I don’t.” It was very courteous, not at all impatient, but the unspoken question underneath it was: “Me? What are we still talking about me for?”

I’m Your Man is out now in cinemas and on Curzon Home Cinema.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion