Constantine the Great

The greatest of the Roman Emperors

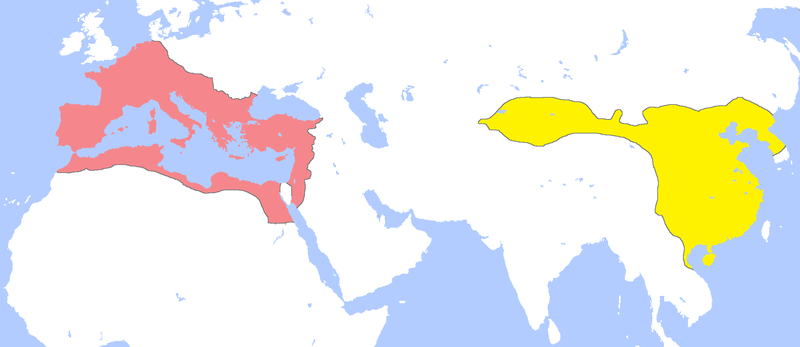

Constantine the Great (27 February 272 AD — 22 May 337 AD) is a towering figure in Roman, European and Western history. It is generally true that social and economic conditions are more important than ‘great men’ in shaping history but Constantine was one of the few people who really did shape history. His decisions to create a new imperial capital in the East, Constantinople, and embrace a new religion, Christianity, had momentous consequences for the history of Europe and the world in general.

The Tetrarchy — Constantine’s Early Years

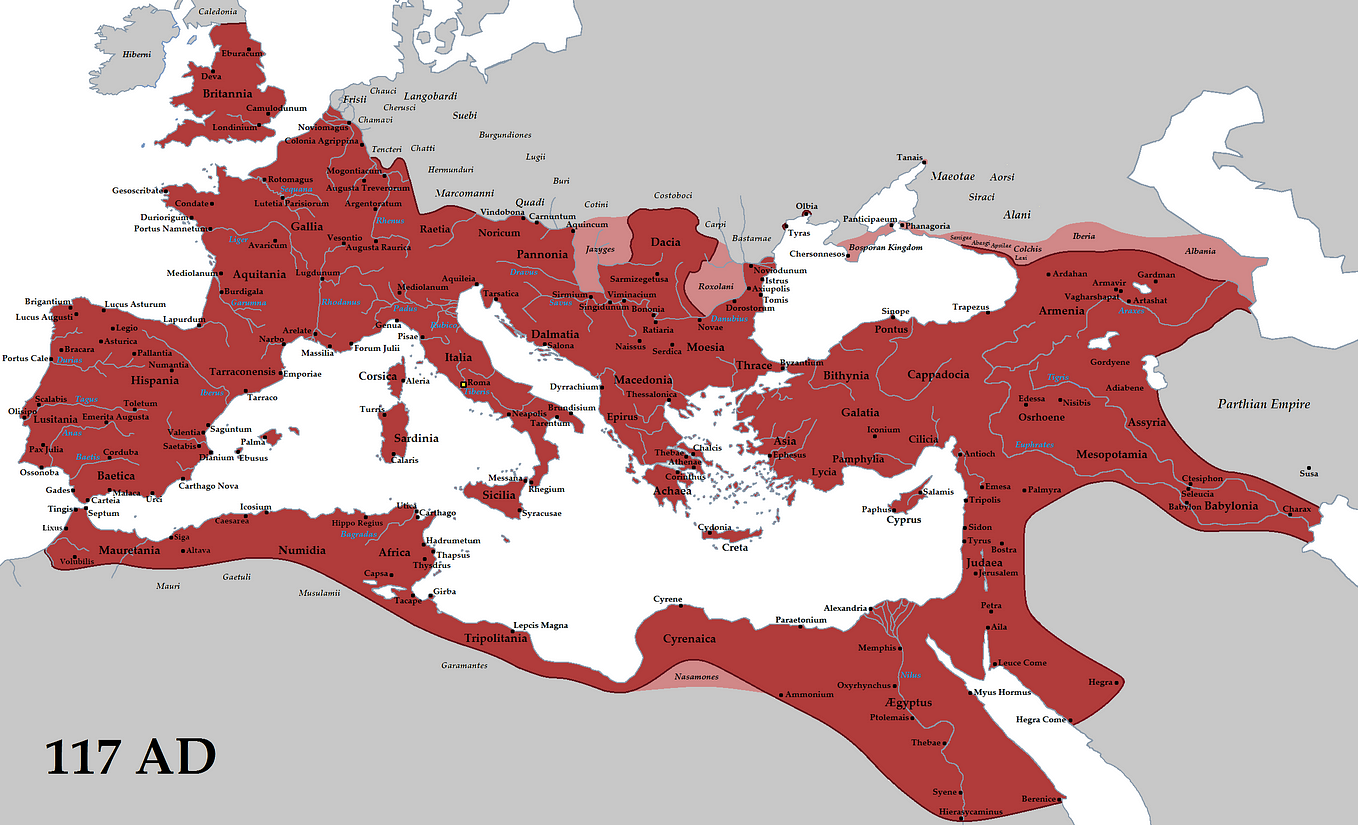

In 284 Diocletian, a military officer, came to the Roman throne. For much of the third century the Roman Empire had been plagued by infighting, secession, coups and civil wars. The Roman Empire faced a resurgent Persian Empire under the Sassanid Dynasty and invasions by barbarian tribes in the Rhine and Danube fronts.

Realizing that the empire was too large and had too many problems for a single ruler to handle, Diocletian administratively divided the empire in two halves, with himself ruling over the Greek East while his colleague Maximian would rule over the Latin West. The two of them would be Augusti. In 293, Diocletian further divided the empire as he and Maximian appointed a Caesar each in their realms to aid them. This administrative system was named the Tetrarchy (rule of four). Constantius, Constantine’s father, was Caesar of Maximian. Constantius was given command over Gaul and Britannia, where he had to put down rebellions and repel barbarian invaders.

Flavius Valerius Constantinus, as was Constantine’s full name, was born in the city of Naissus in modern day Serbia on 27 February 272. Helena, Constantine’s mother, was a woman of low social standing. Constantine spent most of his time with his mother as his father was too busy his with his military tasks. In 288/9, he left Helena to marry Theodora, stepdaughter of Maximian. When Constantius was promoted to Caesar, Constantine was sent to the court of Diocletian in Nicomedia, Asia Minor. There he received formal education on Greek, Latin literature and philosophy.

Constantine’s presence in Diocletian court also served to ensure that Constantius would remain loyal to Diocletian. Constantine served in the armed forces, campaigning against barbarians in the Danube (296) and the Persians in the East (297–299). In 305 Diocletian, being in bad health, retired from the office of Emperor and so did his colleague Maximian. Constantius thus became Augustus of the Western part of the Roman Empire.

That same year Constantius launched a campaign against the Picts in Britain and requested that his son Constantine join him there, which he did. Constantius’ campaign against the Picts was successful but the very next year he died. Constantius’ soldiers hailed Constantine as their new Emperor. Galerius, the Eastern Augustus, was furious but he had to compromise; he recognized Constantine as a Caesar, granting him as his share Britannia, Gaul and Hispania.

Constantine the General — Reuniting the Roman Empire

Constantine showed great military skills and was a competent military commander. In his battles against both barbarians and Roman rivals, Constantine showed his skills on the battlefield as a tactician. In a series of campaigns he managed to reunify the disunited Roman Empire and successfully face barbarian invaders.

After his promotion to Emperor in 306 in Britain, he remained there and drove back the tribes of Picts, securing the Roman control in the northwest. In the winter of 306–307, the Franks invaded Gaul but Constantine defeated them and drove them back beyond the Rhine, capturing two of their kings in the process. In 308 he raided the territory of the Bructeri and in 310 he fought against the Franks in the northern Rhine.

His greatest military victories, however, were achieved against his Roman opponents. In the spring of 312, he and his army (of about 40,000 men) crossed the Cottian Alps to face Maxentius, Maximian’s son who had seized control of Rome and northern Italy. He quickly took over the heavily fortified town of Segusium. He approached the city of Augusta Taurinorum, where he faced Maxentius’ cavalry. Constantine extended the frontage of his battle line, allowing Maxentius’ cavalry to ride into the middle of his array. As his army outflanked that of the enemy, Constantine’s more lightly armored and mobile cavalry were able to charge in on the exposed flanks of the Maxentian cataphracts. Constantine emerged victorious. He then quickly advanced to Verona, where Ruricius Pompeianus (a Maxentian general) was camped as the Adige river offered protection from three sides. Constantine ordered a force of his to march north of the town in order to cross the river unnoticed. Ruricius sent a large detachment to counter Constantine’s force but he was defeated. Constantine laid siege on the town and Ruricius led his army out to offer battle, but he was defeated. Although he escaped the city and brought reinforcements, thus placing Constantine on the difficult position of having to fight on two fronts, Constantine moved against him with a portion of his army and defeated him once again, this time killing Ruricius.

Maxentius fortified Rome and prepared for a siege, ordering all bridges across the Tiber cut. His army was twice as large as Constantine’s but he did not feel certain that he would emerge victorious in a siege and decided to meet him in battle, building a temporary boat bridge across the Tiber. He organized his forces in long lines, with their backs to the river. It is said by Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea, and Lactantius, author and advisor to Constantine, that Constantine became convinced that the Christian God was helping him. According to Eusebius’ version of the story, which is the more popular, before the battle Constantine looked at the sun and saw a cross of light with the Greek words Εν Τούτῳ Νίκα (In this [sign], you conquer). This vision has been sometimes explained as a solar phenomenon (called ‘sun dog’). Constantine was unsure of this vision but the night he had a dream in which Christ explained to him that he should use this sign to prevail over his enemies. In the day of the battle, Constantine ordered his cavalry to charge and they broke Maxentius’ cavalry. He then ordered his infantry to march against the Maxentian infantry. His infantry pushed Maxentius’ soldiers into the Tiber river, where many were slaughtered or drowned. Maxentius himself drowned.

Constantine thus emerged as ruler of the Western Roman Empire and faced Licinius, ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire, for supremacy over the Roman world. In 314 (or 316), Constantine met Licinius’ forces on the battle of Cibalae. The opposing armies met on the plain between the rivers Save and Drave near the town of Cibalae. Despite fierce resistance, Constantine emerged victorious. In 317, Constantine clashed against with Licinius in the battle of Mardia and once again emerged victorious, although not decisively. Constantine made peace in exchange for getting the dioceses of Pannonia and Macedonia. In 322 and 323 he campaigned against the Sarmatians and Goths respectively.

In 324, the final confrontation took place. Licinius presented himself and his Gothic mercenaries as defenders of the pagan traditions while Constantine and his Frankish allies marched as defenders of Christianity. In the battle of Adrianople, Constantine used a ruse to get his army across the Hebrus river; he noticed a suitable point where the river narrowed, but he ordered materials to be brought on another location on the river, so as to give to his enemies the false impression that he would be building a bridge there. He then led his army through the narrow river crossing and with a surprise attack he defeated the enemy army. Constantine’s son Crispus dealt Licinius a catastrophic defeat at the naval battle of the Hellespont and Constantine crossed across the Bosphorus to Bithynia. In a battle near Chrysopolis, he routed his opponent and emerged as the sole Emperor of Rome. In 332 he campaigned against the Goths and defeated them. In 334, he defeated the Sarmatian tribes.

Constantine’s military campaigns show his skills as tactician and as one of the greatest Roman commanders.

A New Capital — The City of Constantine

The foundation of Constantinople by Constantine as a new imperial capital would eventually move the center of the empire towards of the East. The city was founded in 324 and dedicated on 11 May 330. Constantinople would serve as an imperial capital for more than 16 centuries (first as Byzantine and then as Ottoman capital).

By the third century, Rome was no longer the center of the Empire; soldier-emperors tended to eschew Rome (which was still the capital) and the court followed behind them. During the Tetrarchy, the Tetrarchs established their own capitals/centers outside of Italy. Diocletian himself established his base in Nicomedia. Other Tetrarchic capitals/centers included Mediolanum, Sirmium, and Trevorum, all close to the frontiers. Rome never really recovered its previous dominant position as capital of the Roman Empire; in the fifth century, the Western Roman Empire had as its capital the city of Ravenna.

The reason for this has to do with the changing needs of the Empire; while Rome was a good capital for an Empire at peace with largely stable borders, the Empire of the third and fourth centuries was under pressure by the barbarian Germanic tribes in the Rhine and Danube and from the Sassanid Persian Empire in the East. The Emperors thus needed as their capital/center a city that was closer to the frontiers and which would allow them to adequately defend the Empire.

Constantinople fulfilled that role, for the Eastern part of the Empire that is. It was close to the frontier of the Danube, from where tribes such as the Goths and later the Huns raided, and to the eastern frontier in Asia Minor and Mesopotamia with the Persian Empire. It was in a good strategic position also due to its highly defensible position; it was protected by the Balkans and Asia Minor as any invader would have to pass through those two territories to get to Constantinople (that is one of the reasons why the Byzantine Empire did not collapse in the seventh century to the Arab onslaught in the same way the Persians did). It was also surrounded by sea on three sides and was in a good position for trade.

Constantine modeled this ‘New Rome’ after the old one (seven hills, forum, exemption from taxation and lavish entertainment, etc) and also laid foundations for grand buildings such as the Great Palace, the cathedral of Hagia Sophia (which would later be rebuilt much grander by Justinian), Hippodrome, baths, etch. He also established a Senate, which was expanded by his successor Constantius II and grew in importance.

The foundation of Constantinople would allow the Easter part of the Roman Empire (better known as Byzantine Empire) to survive a thousand years after the fall of the Western Empire. Even after the fall of Byzantium, the city would serve as the imperial capital for the Ottoman Empire.

Constantine as an Administrator

Constantine was a capable ruler and administrator who undertook reforms necessary for the stabilization of the Roman Empire. His reformist agenda was a continuation of Diocletian’s earlier reforms, so Diocletian must get part of the credit for those reforms, however Constantine both improved those reforms and, in some cases, moved to different directions than Diocletian’s agenda.

Constantine reversed the pro-equestrian trend of his predecessors, who since the mid-3rd century had been favoring equestrians, and instead raised many administrative posts to the senatorial rank and opened those offices to the old aristocracy. Although the senate remained devoid of any real powers, the senators could now compete with upstart bureaucrats for the high offices. Constantine thus reintegrated the old senatorial elite into the imperial administration.

His most important reform though was his monetary one. Runaway inflation had been a major problem for the empire since the crisis of the third century. Diocletian attempted to solve this problem by trying to reestablish trustworthy minting of silver and billon coins but his attempts ended up in failure. Constantine, instead of trying to restore the silver currency, concentrated on minting large quantities of good standard gold pieces, the Solidus or Nomisma. Solidus has been called the dollar of the Middle Ages and was highly valued in Western Europe. Its value remained largely stable until the crisis of the eleventh century and the devaluations of that period. A large part of Byzantium’s prosperity thus was a result of Constantine’s monetary reform.

The Christian Emperor— Equal to the Apostles

Constantine’s decision to embrace the Christian religion would have momentous effects in European and global history. While Christianity was spreading in the Greek East, the Christians were still a minority among the empire’s subjects.

The growth of Christianity in the Greek East can be attributed to a number of factors. The most important is that there was a lingua franca in the Roman East that allowed the spread of the word of the new religion among ethnically different populations: that language was Greek (Koine Greek, to be more precise). That was a result of the conquests of Alexander the Great (20/21 July 356 BC — 10/11 June 323 BC) and the subsequent Hellenistic Kingdoms that emerged after his death. The eastern territories of Rome coincided in large part with the western territories of Alexander’s Empire/Hellenistic Kingdoms. Another reason for the growth of Christianity was its appeal to the lower classes and slaves. Christianity offered hope of an afterlife that was enticing to slaves and poor people who suffered in their current life. The early Christian communities also encouraged Christians to offer support to those in need (for example offering free food, etch).

Nevertheless, by the time of Constantine, the Christian population of the whole Roman Empire was perhaps about 10%, concentrated mostly in the East although the religion had also made some progress in the West too. While Constantine did not make Christianity the official religion of the empire, his favor (and that of his sons) towards the new religion as well as his support for the Church as an institution and his granting of privileges to bishops such as the privilege of offering judgments in civil cases and the right to use the public posting system for travel, cemented Christianity’s role as the empire’s religion and accelerated the growth of the Christian population by prompting people to convert.

Constantine convened the Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (325), solving the Christological issue of the divine nature of God the Son and his relationship to God the Father. Arianism, the first of the ‘heretical’ doctrines, which asserted that Jesus the Son of God was distinct from God the Father and subordinate to Him, was denounced as heresy. The council also created the Nicene Creed, a declaration and summary of the Christian faith, established uniform observance of the date of Easter and promulgated an early version of the canon law, a set of regulations regarding the organization of the Christian Church.

Constantine’s presence in the council meant that the Roman Emperor now had a role to play in shaping Christian doctrine and protecting the ‘correct faith’ (Orthodoxy) from heresies. As the Roman Empire became Christian, the Roman Emperor began to be considered God’s Vicar on Earth.

Constantine, although a Christian, delayed his baptism. Baptism could absolve sins, as such more than a few Christians of that era put off being baptized until near death so that they could be absolved (as much as possible) of their sins and, hopefully, earn a place in paradise. This was especially true for someone like Constantine, who as a ruler had committed many sins (including murders of relatives and killing enemies in war). He was eventually baptized in 337 by the bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia, in that city. Constantine died soon after at a suburban villa called Achyron.

Following his death, Constantine’s body was put in a golden coffin and escorted to the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. The coffin was put in a magnificent porphyry sarcophagus surrounded by the symbolic cenotaphs of the twelve apostles. The symbolism was quite clear. To this day, he is considered an equal of the Apostles (Ισαπόστολος) and a Saint by the Orthodox church.

Whether one views the Christianization of the empire as a positive or negative development is up to one’s personal views, but no one can deny its importance in world history. Christianity played a crucial role in European culture (both Western and Eastern) and through the colonization of European powers, that culture spread all over the world. It influenced arts, philosophy, morality and the way of thinking and living. Thus Constantine’s decisions and their influence cannot be overstated.