When you analyse Australia’s wastewater, the story of methamphetamine use is shocking. According to the Australia Criminal Intelligence Commission, in 2021 we ranked the highest of 20 countries in per capita use.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reports there has been a rapid increase in the number of deaths involving meth and other stimulants, with the death rate in 2021 almost four times higher than that in 2000 (1.8 deaths compared with 0.5 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively). It is abundant and easy to obtain.

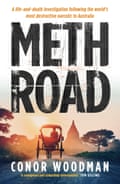

The UK author and journalist Conor Woodman has tracked the supply of meth to Australia, examined addiction and use and the policing and treatment of that use. Here he answers 10 questions about Meth Road: A life-and-death investigation following the world’s most destructive narcotic to Australia.

Your book charts an extraordinary journey from hidden jungle laboratories in south-east Asia to the streets of Brisbane, mapping the movement of methamphetamine to this country, which has the highest addiction rates of this drug in the world. What made you start this story?

This story really found me. A friend of mine was working for one of the TV streamers on a film about meth labs in Myanmar but when a contributor got shot, the production team pulled out. I immediately felt that there was an opportunity to pick up the threads and so I flew to Myanmar soon after to begin my research.

Once I realised how closely the drug trade was linked to the ongoing civil conflict in Myanmar, I was determined to find out more so I stayed until I got right to the root of the source.

The book is broken down into three parts – supply, demand and solutions – why did you decide to start with laying out the processes and geography of supply?

For me, the first big shock of all this was discovering that there was a huge drug trading nexus located in a war-torn south-east Asian country that hardly ever gets talked about. We tend to think that all the world’s biggest drug supply chains start in Latin America or Afghanistan but Myanmar is right up there with them as a major player.

I had a lot more compassion for individual users of methamphetamine in places like Australia once I started to understand the size of the industrial complex that underpins the country’s meth supply. The country, indeed the whole region, is being flooded with high grade/low cost methamphetamine and I wanted readers to get that from the start.

What separates meth from other drugs?

Meth is so worryingly insidious in its modus operandi. The dopamine response that it engenders in users makes it especially addictive and corrosive. You might go out and take MDMA or cocaine on a night out, but there’s going to come a point where your body says “enough” and you have to sleep. But not so with meth. I was shocked to see users go at it for five or six days straight without sleep.

Does anything compare?

Heroin is maybe the obvious comparison to make when thinking about methamphetamine but alcohol is perhaps an even better one. Alcohol and meth do a very good job of taking you out of yourself without rendering you incapable of functioning. That’s maybe what makes them both so dangerous. Meth and alcohol addicts can function in society for a long time before their use eventually catches up with them and gets out of control.

The stories of addiction you have in your book are utterly sobering and also often frightening. What unites the users of meth?

Too often I met people using meth who had a story of historic abuse to tell. Sometimes physical, mental or even sexual. Often going back to childhood trauma. There’s something very dissociative about methamphetamine that I think helps users to pack those painful feelings and memories away.

The other common thread I observed was users self-medicating for what they believed to be undiagnosed ADHD. There’s certainly a similarity between the way meth and a licensed drug such as Adderall work, so some users thought the meth was helping them function better in the world.

How do you de-stigmatise drug use in society and is it really possible?

I think drug use is already widely de-stigmatised, albeit in communities of people who use drugs. Middle class cocaine users who share a gram at a dinner party have normalised that behaviour for each other but they might still consider anyone using heroin to be a “junkie”. Likewise, a group of people down the pub who get drunk together on a Saturday night are normalising their behaviour while at the same time holding a meth user in contempt.

The question is “can we de-stigmatise the use of drugs that we don’t personally do?” I think that requires a bit of realism from society. The majority of people in western societies partake in some form of drug use to help them to wind down, so it’s a question of having some respect for people making a different choice to your own and having some empathy if ever that choice becomes problematic. People make bad choices. They don’t need you to punish them for it.

What did you discover about Australia and its approach to drugs?

after newsletter promotion

I was surprised how socially conservative Australia can be. The international impression of Australians is that they’re pretty laid back and easy going but the country’s drug policy is far from that. The use of drug dogs at music festivals, for example, is positively barbaric. Having said that, I met a lot of very smart and compassionate people working in this area in Australia so I’m optimistic that reform and progress are possible.

The research being done now in Australia suggests that there could be a growing appetite for change among the public and a consensus around the need for more investment in harm minimisation and rehabilitation. I’d like to see that opportunity capitalised on.

Was being an outsider an advantage here?

I’m fully prepared to cop the flak from those who say that I should stick to my own patch. Why not write a book about the UK’s many drug problems? It’s a fair point. But still, a fresh pair of eyes is sometimes an advantage. I came to Australia with a very open mind and tried to always ask myself “what do people want?” I think when you’re already entrenched in your views or embroiled in a longstanding argument (as many people seem to be over there) it’s easy to lose sight of that important question.

What preconceptions did you start out with but have changed your mind about?

I wondered when I started this book if I would try methamphetamine myself so as to be able to write about the experience first-hand. But once I saw the drug up close and the way it affected people, I changed my mind. I have a very different view about meth now. I see it as a very pernicious drug and a bad choice for recreational use.

What would meaningful progress in Australia look like to you?

First up, the education around meth has to change. No more TV advertisements of crazed meth-heads tearing apart ER rooms. I would prefer to see people who have lived experiences of meth take a lead in educating others about its potential dangers.

Secondly, state policing needs to take a step back. Once meth has hit the street, I would argue that control of supply has already been lost. It’s far more economical and effective for the AFP and Australian Border Force to focus on supply reduction at a national and international level while reallocating that part of the state police budget to harm minimisation strategies. When money is tight, it’s important to spend it wisely.

To help make that move practical, the next step would be to decriminalise possession for personal use. That was the conclusion of the NSW’s own report into methamphetamine in the state so I’m not saying anything that far smarter people than me haven’t already said.

The current strategy clearly isn’t working so it must be time to try something new.

Meth Road by Conor Woodman (Allen & Unwin) is out now