Why Was the Royal Marriages Act of 1772 Created?

George III had the Royal Marriages Act of 1772 created to stop his relations from marrying against his will.

The Business of Royal Marriages

George III (1738-1820) was an unhappy king. In 1772, he learned that his brother Henry, Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn (1745-1790), had had the audacity to marry a widow named Anne Horton (1743-1808) in October 1771. George believed that the match could severely damage the standing of the monarchy. Anne Horton had married well above her status. Her first husband had been a commoner; her father only held an Irish peerage. English peerages were superior but still not grand enough to assume that such a marriage would meet with George's approval.

The business of royal marriages was preserving the dynasty and securing international marriages, often between relations, to ensure peace, prestige, and alliances for a better world. Love and lust were not key motivators for marriage; these emotions were best left for mistresses (if you had to have them), which George III didn't. He had chosen his dynastic wife extremely carefully; Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744-1818) met his expectations of a queen-wife.

George wasn't the first ruler to find out that his sibling had married without a thought for tradition or power. Charles II (1630-1685) had been amazed to learn that his brother James, Duke of York and later King James II/VII (1633-1701), had been secretly married to courtier Anne Hyde (1637-1671) but accepted the match, probably because she was heavily pregnant, and organized an official but private late-night wedding which was held weeks before the arrival of Charles, created Duke of Cambridge, who was tragically short-lived.

The Royal Marriages Act of 1772

Parliament, led by Lord Frederick North, wasn't truly concerned about Henry's marriage, but they were browbeaten by George into action. The king declared that never again would a royal be able to marry without the monarch's counsel and approval. An Act of Parliament was prepared. On the 1st of April 1772, it was given royal assent and became law. George had stamped his royal foot, and the vibrations were felt into the 20th century.

"That no descendant of the body of his late majesty King George the Second, male or female, (other than the issue of princesses who have married, or may hereafter marry, into foreign families) shall be capable of contracting matrimony without the previous consent of his Majesty, his heirs, or successors, signified under the great seal, and declared in council...and that every marriage, or matrimonial contract, of any such descendant, without such consent first had and obtained, shall be null and void, to all intents and purposes whatsoever."

The above rule applied to royals under twenty-five years old. Those who were age twenty-five and above could marry one year after giving notice to the Privy Council unless both the Houses of Parliament (the Commons and the Lords) voted against the union. However, would a parliament ever vote against a determined monarch about a marriage?

A Confession

Within days of the Royal Marriages Act passing into law, another of King George's brothers, William, the Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh (1743-1805,) confessed that he had been secretly married to Maria Walpole, Countess Waldegrave (1736-1807) for six years. Maria was a commoner and illegitimate, the child of Sir Edward Walpole and a postmaster's daughter, Dorothy Clement. Edward was the son of the country's first Prime Minister, Robert Walpole, Earl of Orford. Maria was well known to the royal family; she had grown up at Frogmore House on the Windsor estate.

Stunned, George III did not force the couple to separate because the union predated the Royal Marriages Act, but he never formally received Maria at court. William and Maria had three children who were accepted as a legitimate issue: Sophia, Caroline (who died in infancy), and William. The line died out with William; he married Princess Mary (1776-1857), one of George III's daughters, but they had no children.

Recommended

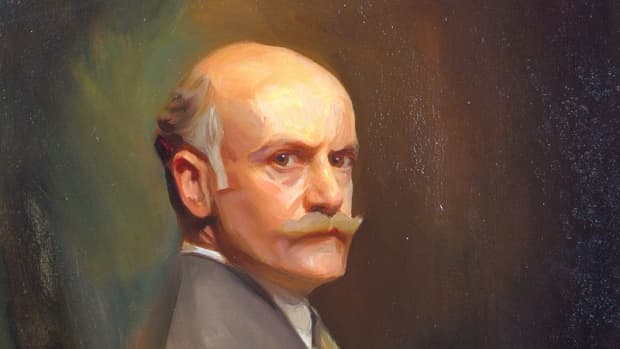

George, Duke of Cambridge (1819-1904), who married against the Royal Marriages Act

Collodion of Prince George, 1855, by Roger Fenton (Public Domain.)

The Impact on Later Royal Matches

Royal marriages without the king or queen's consent have been met with outrage or resignation. George III's sons George, Prince of Wales (1762-1830), and Augustus, Duke of Sussex (1773-1843), had their secret marriages to Maria Fitzherbert (1756-1857) and Lady Augusta Murray (1761-1830) annulled by him. Maria was a Catholic widow, and both women lacked royal blood. Augustus had two children with Augusta, but they were not recognized by the king. After Augustus and Augusta, who never officially held the title Duchess of Sussex, parted, he married again, this time without seeking Queen Victoria's approval. His bride, Lady Cecilia Underwood (1789-1873), was created the Duchess of Inverness in her own right by Victoria, who had great affection for her uncle. The queen didn't officially approve or disapprove of the match because if she had accepted it, there would have been questions about why George III hadn't recognized Augusta and the two children from that marriage.

Queen Victoria's cousin George, Duke of Cambridge (1819-1904), married a pregnant actress, Sarah Fairbrother (1814-1890), without heeding the Act's rules. Sarah used the surname FitzGeorge and the marriage was referred to as morganatic, but it never happened according to the Royal Marriages Act. The children were not eligible to hold their father's titles.

Group Captain Peter Townsend (1914-1995) was considered unsuitable as a husband for Princess Margaret (1930-2002)

Recent History

Princess Margaret (1930-2002), Elizabeth II's (b. 1926) late sister, faced a dilemma in the 1950s when she fell in love with divorced equerry Group Captain Peter Townsend (1914-1995). Elizabeth was the head of the Church of England, which frowned on divorce. The queen demurred from saying no to their union but pointed out that to marry him, even via the Privy Council and parliamentary approval method, Margaret would have to sacrifice her royal life, and essentially, she would become Mrs. Margaret Townsend, housewife, sister of the queen, but with no duties. The noble sacrifice of the love to duty was made.

An exception to the rule was Edward VIII (1894-1972). When he married double divorcee Wallis Simpson (1896-1986) after choosing her over his role as king and head of the church, he was permitted to do so as Duke of Windsor without his brother George VI's (1895-1953) consent. This had been stipulated in his abdication declaration in 1936. It also stated that if the Duke and Duchess of Windsor had issues, they were exempt from the line of succession.

In 2011, the Royal Marriages Act was repealed. The Perth Agreement and The Succession of the Crown Act 2013 allowed royals greater freedom over who they could marry. Only the first six people in the line of succession require the monarch's approval so, in principle, Charles, Prince of Wales, William, Duke of Cambridge, Prince George of Cambridge, Princess Charlotte of Cambridge, Prince Louis of Cambridge, and Henry (Harry, Duke of Sussex) are the only royals affected.

Sources

- Royal Marriages Act 1772 (repealed)

An Act for better regulating the future Marriages of the Royal Family. - Changes To Legislation

- Succession to the Crown Act 2013

An Act to make succession to the Crown not depend on gender; to make provision about Royal Marriages; and for connected purposes. - Royal Marriages | Law & Religion UK

© 2021 Joanne Hayle