The wife of William Blake, Catherine, was his partner in both life and work, making, mixing and applying his paint colours, according to curators at Tate Britain, who will open their biggest exhibition of the work of the radical British artist and poet this week.

Rather than celebrating Catherine by displaying the handful of surviving works known to have been made by her alone, the gallery has chosen instead to point out her unacknowledged daily involvement in her husband’s idiosyncratic work.

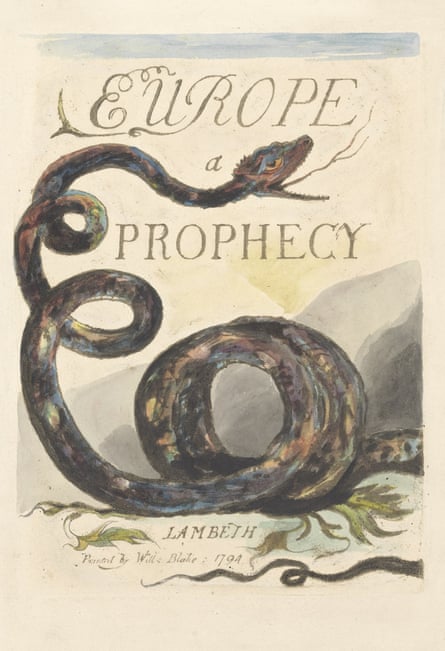

Prominent among the exhibits to go on show this week, alongside previously unseen illustrated pages bearing his most famous lines, “Tyger, Tyger, burning bright,” will be a book cover coloured by Catherine.

“We have not sufficiently trumpeted Catherine’s involvement before, and this book, Europe: A Prophecy, dates from 1794 and its cover was coloured by her,” said curator Amy Concannon. “It makes it clear how she worked by his side.”

Catherine was central to Blake’s printing and colouring processes, Concannon argues, and the importance of her work at his side has been neglected.

“She was an assistant when he was printing, which was a critical part of the process,” she said. “It is thought she was a ‘clean-hands operative’ on the press at times when Blake’s hands were full of ink from running the rollers. She worked with him, we now think, from early 1790s and then in the 1810s and 1820s.

“We know she must have been responsible for a lot of the work from some praise Blake gives her around this time. He was working as a jobbing engraver during the day and so in the evenings they had to work together to produce his own works and meet the demand.”

A letter from romantic painter Samuel Palmer refers to a colour as “Mrs Blake’s white”, and she carried out most elements of the design and production with her husband. Blake’s 1863 biographer, Alexander Gilchrist, was certainly convinced of her input, writing: “The poet and his wife did everything in making the book – writing, designing, printing, engraving – everything except manufacturing the paper: the very ink, or colour rather, they did make.”

Once described as the madder of the two, Blake’s wife was born in Battersea in 1762, the daughter of a market gardener. She met the artist at the age of 19 and they were married 1782, spending most of the rest of their lives side by side until his death in 1827, despite this fact she once commented that she often felt the absence of her visionary spouse since he seemed to be “in Paradise” rather than with her.

The Tate Britain exhibition, which features more than 300 works and will run from 11 September until 2 February 2020, includes more bound copies of their work than usual, allowing visitors to see the images and poems in their intended form, rather than as separate images.

“He had worked out a way to print text on the same page as an image and this was his innovative product, his USP if you like, so we are showing 11 rare books, some of which have never been shown before, which are still intact in their bindings,” said Concannon.

The provenance of these ground-breaking books of illustrated poetry is also a key part of the Blakes’ story. One belonged to the Swiss artist Henry Fuseli and another to painter George Romney. The book with the cover coloured by Catherine, one of only nine known copies of Europe: A Prophecy, was owned by Isaac Disraeli, father of Benjamin, who once described how his guests would “desport themselves” around a table with Blake’s books lit for them by his bright new state-of-the-art Argand lamp and all of them delighted by his engraved images of “angels, devils, giants, dwarves, saints, sinners, senators and chimney sweeps”.

Catherine continued to make prints and went on selling Blake’s images during the four years following William’s death. She lived on the proceeds in London’s Fitzrovia until her own death in 1831.