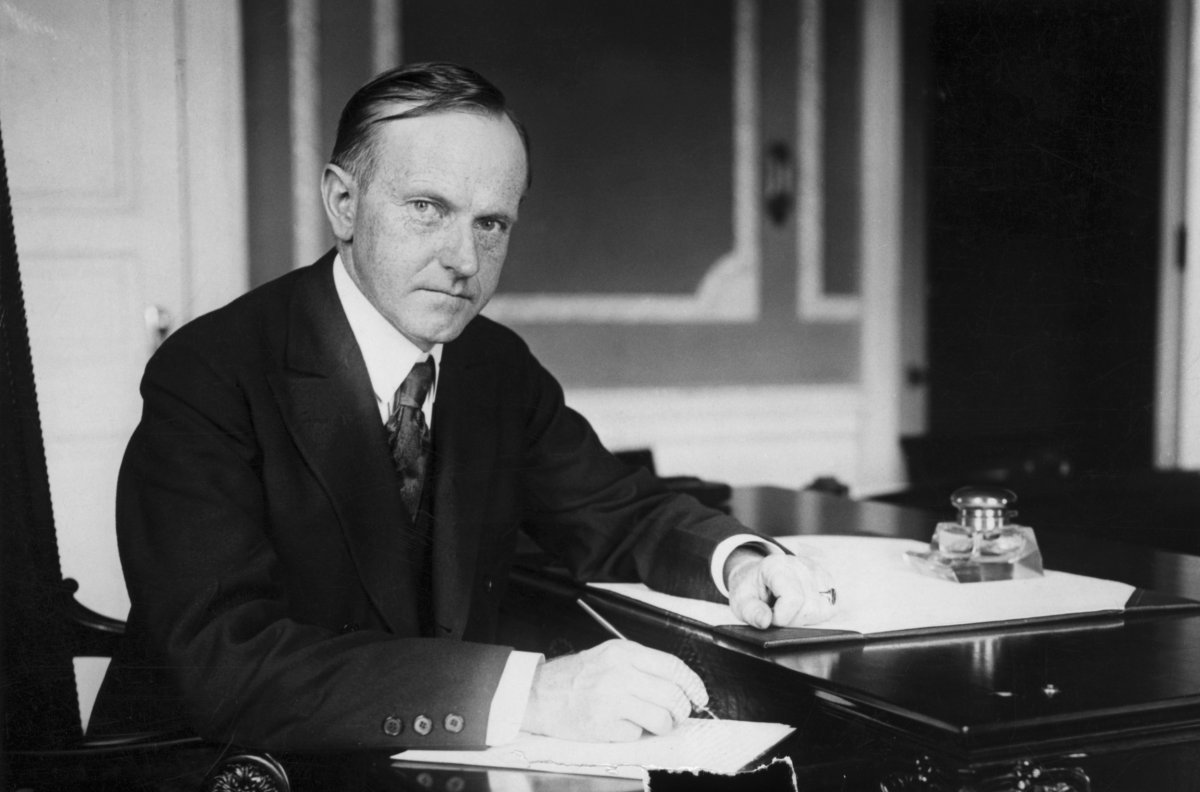

He was born in a farmhouse in a small rural town, Plymouth Notch, Vermont, in 1872. He would serve in 10 public offices, from city councilman to mayor, and from the governor's mansion in Massachusetts to the White House as America's 30th president. What makes Calvin Coolidge's life so compelling is not how far he traveled from his roots but how far those roots traveled with him. Those roots shaped everything from how he governed to how he lived and spoke.

In an age of narcissistic, strident and self-promoting politicians, a reflection no doubt of the relentlessly narcissistic nature of our modern communications culture, Coolidge's story is a worthy rebuttal. And worthy of reflection too.

We need not look further than his own autobiography, recently released by ISI Books, with a forward by historian Amity Shlaes, who chairs the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation's board, and Matt Denhart, its president.

Coolidge's complete memoir is a mere 246 pages long. By contrast, President Barack Obama's first in a two-volume set is 768 pages. "Brevity is the soul of wit," Shakespeare wrote in Hamlet. It can also be, as Coolidge's memoir proves, the soul of wisdom.

Much of his nature and character was shaped by his father, who ran a successful country store. "He was a good businessman, a very hard worker, and did not like to see things wasted," Coolidge wrote. "He trusted nearly everybody, but lost a surprisingly small amount. Sometimes people he had not seen for years would return and pay him the whole bill."

His father was also a man of many practical talents. "He kept tools for mending shoes and harnesses and repairing water pipes and tinware. The lines he laid out were true and straight, and the curves regular. The work he did endured," Coolidge wrote about his father's all-around talents. "If there was any physical requirement of country life which he could not perform, I do not know what it was."

Coolidge's mother was ill for most of his young life, but from her too he learned important things. "She was practically an invalid ever after I could remember her, but used what strength she had in lavish care upon me and my sister, who was three years younger," Coolidge wrote. "There was a touch of mysticism and poetry in her nature which made her love to gaze at the purple sunsets and watch the evening stars."

Coolidge knew grief, losing his mother before he was a teenager. "When she knew that her end was near she called us children to her bedside, where we knelt down to receive her final parting blessing. In an hour she was gone," Coolidge wrote. "It was her thirty-ninth birthday. I was twelve years old. We laid her away in the blustering snows of March. The greatest grief that can come to a boy came to me. Life was never to seem the same again."

His parents affected his life, but so did the adults around him. "The Notch was made up of people of exemplary habits. Their speech was clean and their lives were above reproach," Coolidge wrote. "Credit was good and there was money in the savings bank. The break of day saw them stirring. Their industry continued until twilight. They were without exception a people of faith and charity and of good works."

The men he grew up around fought in the Civil War under generals named Sherman, Meade and Grant, but there was no space for boasting. "They were not talkative and took their military service in a matter of fact way, not as anything to brag about but merely as something they did because it ought to be done."

The inhabitants of the Notch also taught Coolidge a lot about how to treat people, especially along wealth and class lines. "They drew no class distinctions except towards those who assumed superior airs," he wrote. "Those they held in contempt."

Coolidge wasn't finished, summarizing the place he was born and raised. "It was all close to nature and in accordance with the ways of nature," he wrote. "The streams ran clear. The roads, the woods, the fields, the people—all were clean."

As he grew older, Coolidge was aware of the cultural benefits of living in a big city. But he valued his rural upbringing nonetheless. "Country life does not always have breadth, but it has depth," he wrote. "It is neither artificial nor superficial, but is kept close to the realities. If it did not afford me the best that there was, it abundantly provided the best that there was for me."

He wrote beautifully about his time at Amherst College and about two of his professors. "The whole course was a thesis on good citizenship and good government," he wrote of professor Anson Morse's American history class. "Those who took it came to a clearer comprehension not only of their rights and liberties but of their duties and responsibilities."

His philosophy and ethics professor, Charles Garman, taught students much about public service. "The only hope of perfecting human relationship is in accordance with the law of service under which men are not so solicitous about what they shall get as they are about what they shall give," Coolidge wrote about the things Garland taught him. "Yet people are entitled to the rewards of their industry. What they earn is theirs, no matter how small or how great. But the possession of property carries the obligation to use it in a larger service.

Important lessons about work were also taught. "Our talents are given us in order that we may serve ourselves and our fellow men. Work is the expression of intelligent action for a specified end," Coolidge wrote. "It is not industry, but idleness, that is degrading. All kinds of work from the most menial service to the most exalted station are alike honorable."

Of his wife and the love of his life, Grace, who taught deaf children, he said this after nearly 25 years of marriage: "I have seen so much fiction written on this subject that I may be pardoned for relating the plain facts. We thought we were made for each other. For almost a quarter of a century she has borne with my infirmities, and I have rejoiced in her graces."

Coolidge had this to say about the growing spirit of revolution and radical progressivism in the air. "It consisted of the claim in general that in some way the government was to be blamed because everybody was not prosperous, because it was necessary to work for a living, and because our written constitutions, the legislatures, and the courts protected the rights of private owners," he wrote.

It was 15 simple words spoken as governor during the 1919 Boston Police Strike that brought him national acclaim: "There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time."

Coolidge would soon become vice president of the United States. When President Warren Harding died unexpectedly in San Francisco in 1923, "Silent Cal" became our nation's leader. He ran successfully for the nation's highest office in 1924, and Republicans expected him to run a second time. Vacationing in South Dakota, he issued a short statement that shocked everyone, friends and opponents alike: "I do not choose to run for President in 1928."

In his autobiography, he explained his thoughts on the subject. "It is a great advantage to a President, and a major source of safety to the country, for him to know that he is not a great man," he wrote. "When a man begins to feel that he is the only one who can lead in this republic, he is guilty of treason to the spirit of our institutions."

Coolidge also wrote elegantly about the weight of holding any office for too long. "It is difficult for men in high office to avoid the malady of self-delusion," he admitted. "They are always surrounded by worshipers. They are constantly, and for the most part sincerely, assured of their greatness. They live in an artificial atmosphere of adulation and exaltation which sooner or later impairs their judgment. They are in grave danger of becoming careless and arrogant."

He closed things out with this observation: "The chances of having wise and faithful public service are increased by a change in the Presidential office after a moderate length of time."

Coolidge's record was worthy of a boast or two. During his nearly six years in office, the national debt, the federal budget and consumer prices were all reduced. Unemployment was down to 3.6 percent, while the nation's gross domestic product grew over 13 percent.

In her biography of Coolidge, Shlaes noted his aptitude for brevity and his ability to make "a virtue out of inaction." One of his many well-known one-liners may have best summarized his thoughts about Congress's propensity for passing laws. "It is much more important to kill bad bills," he said, "than to pass good ones."

Even his wit made little room for waste. When Coolidge and his wife were given separate tours of a chicken farm, his wife asked her host if the rooster performed coitus more than once a day. "Dozens of times," the host told her. "Tell that to the president," she joked. When told about the exchange, Coolidge asked his host, "Same hen every time?" After the host replied, "A different one each time," her husband had the perfect comeback: "Tell that to Mrs. Coolidge."

Coolidge died in his New England home on January 5, 1933. Just as he would have wanted it, his funeral lasted a mere 22 minutes. The Great Refrainer, as he was known, died as he had lived, with self-restraint, self-awareness and grace. And with a love and regard for the country he served—and its Constitution—intact.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.