Scene Change: Biodome Migration, Space for Life natural science complex, Montreal, Quebec

A renovation of Montreal’s Biodome recasts the iconic destination with streamlined circulation, ethereal textile walls, and bird’s-eye vantage points.

PROJECT Biodome Migration, Space for Life natural science complex, Montreal, Quebec

ARCHITECTS KANVA in collaboration with NEUF Architect(e)s

PHOTOS Marc Cramer, unless otherwise noted

Montreal’s grandest—and possibly, its most beautiful—architectural gesture of the past century was the work of French architect Roger Taillibert, responsible for the design of the 1976 Olympic Games’ main sporting structures. Unfortunately, partly because of its novelty, the complex was shrouded in controversy. The unfinished stadium, in particular, attracted a lot of attention before, during, and after the Games.

The real star of the complex, however, is arguably the stadium’s immediate neighbour, the velodrome. City engineers involved in its construction described its structure as being 10 times more complex than the stadium’s. Apart from its technical performance, the 172-metre-long velodrome had—and retains—an exquisite quality about it. The building’s roof is particularly expressive, with splayed arrays of cat-eye skylights. To quote reviewer John Hix, who wrote about the building in these pages 45 years ago, these gave it the appearance of a “giant Paleozoic trilobite coming to rest at the bottom of the sea.”

Post-Olympic pause

As is too often the case with Olympic facilities around the world, the velodrome ended up being used only sporadically in the years that followed the Games. In 1977, it somewhat awkwardly hosted the Salon de la femme. A couple of years later, Botanical Garden director (and future Montreal mayor) Pierre Bourque saw the velodrome as “an immense greenhouse with a fabulous potential.” He proceeded to organize the 1980 Floralies, an international horticultural exhibition, within its walls. Needless to say, Taillibert was horrified.

But in retrospect, this event was prescient of the building’s future rebirth as the Biodome, a decade later. In the 1980s, scientists working at Montreal’s two zoo locations and at the aquarium became increasingly concerned with the poor conditions of their facilities. The Botanical Garden—across the street from the velodrome—started hosting a series of brainstorming sessions to come up a solution. According to biologist Rachel Léger, the Biodome’s first director, “it is within this context that the Biodome was born.” The new concept—an immersive reproduction of natural ecosystems, set in the spacious velodrome—was intended to become, as Pierre Bourque described it, “a rallying call of hope and faith in the future.”

The transformation

Architectural firm Tétreault Parent Languedoc et associés (now merged with Aedifica)—was called in to do a feasibility study and, eventually, to design the new facility. Architect Pierre Corriveau, who was responsible for the concept, recalls: “We had no way of telling whether the Biodome would be a success. We were therefore careful to come up with a project that would be respectful of the existing structure and make it possible to revert the building back to its original function.” The overnight destruction of the rosewood cycling track somehow put an end to that dream. But otherwise, the architectural team consciously avoided altering the building’s main elements. They also meant to keep the skylit ceiling exposed everywhere they could, including in the building’s central node. The idea was not retained at the time due to the use of this space for displaying information related to the exhibits—a decision that led to the introduction of a low ceiling, blocking the view to the skylights above.

The unusual program involved creating replicas of five ecosystems from the Americas. The hope was to raise public awareness and respect for nature through direct contact with animals and plants living in different regions. The challenge was tremendous. Flora and fauna usually found in tropical rainforests had to thrive under the same roof as Quebec beavers, used to a temperate climate, as well as penguins from the much colder Antarctic. Roughly 500 plant species and 4,500 animals from 250 different species were brought in, thanks to a remarkable international network developed over the years by Montreal’s institutions. Filmmaker Bernard Gosselin documented the final stages of construction in a feature-length NFB film, The Glass Ark.

The Biodome opened on June 24, 1992 to a long lineup of eager visitors. The new amenity attracted 750,000 visitors during its first three months. Attendance fluctuated over the years, eventually settling around 850,000 visitors annually—making it the city’s top permanent paid attraction.

Renewal

In 2014, Espace pour la vie (Space for Life)—a new entity created to oversee all of Montreal’s nature museums—launched an international design competition. It aimed to gather ideas for revamping the Biodome, rehousing the Insectarium, and creating a new glass pavilion for the Botanical Garden. Eight architectural teams were selected to take part in the competition’s second stage: four worked on the future Insectarium, and four others on the Biodome. (The Botanical Garden pavilion was put on hold.)

Montreal-based KANVA and Neuf architect(e)s, working with Spanish studio AZPML, won the competition for revamping the Biodome. The project moved forward with the team of KANVA and Neuf. The client’s message had been quite clear. They asked the designers to “redynamize” the Biodome: “to enhance the immersive experience between visitors and the museum’s distinct ecosystems, as well as to transform the building’s public spaces.” The two subpolar areas needed refreshing, along with the Gulf of St. Lawrence ecosystem. Otherwise, the Tropical Rainforest and the Laurentian Maple Forest ecosystems were thriving. The largest concern was the building’s public spaces, which had become outdated and needed a major overhaul.

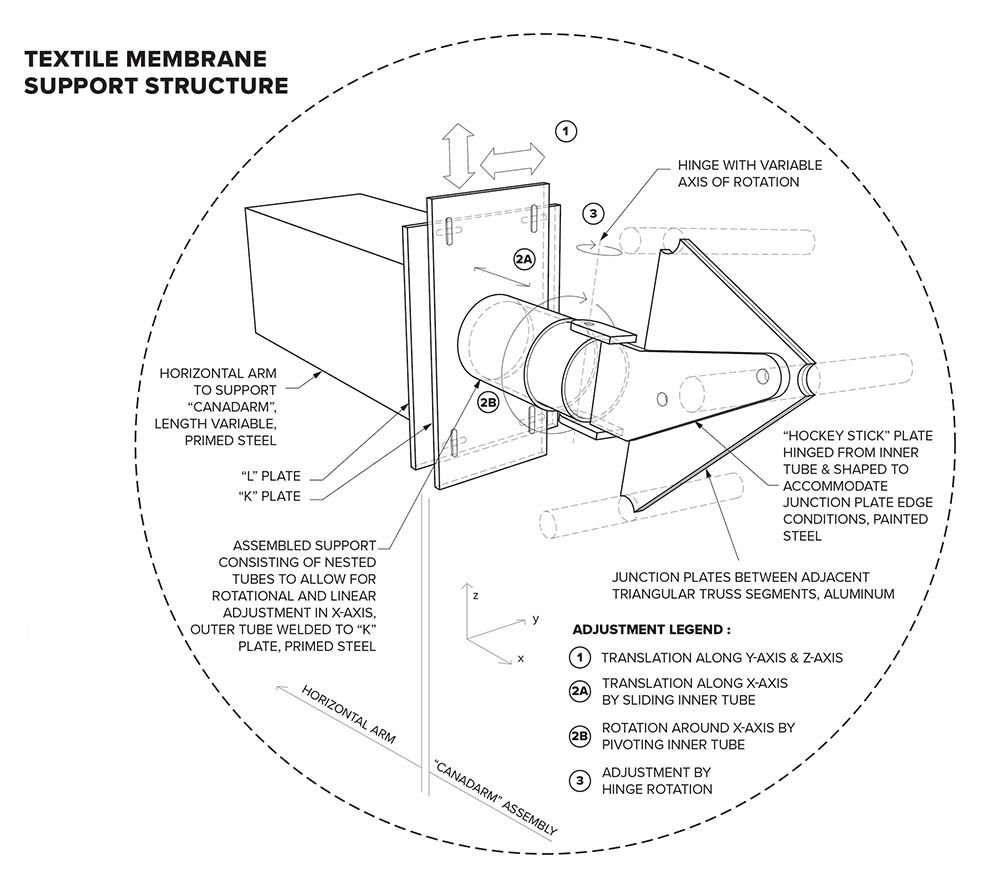

KANVA’s impactful first move was to remove the bleachers ringing the concrete structure above the main entrance, thus freeing the view to the skylit vault above. The effect is dramatic, exposing not only the elegant skylights but also the building’s impressive Y-shaped concrete legs. The second strategy centered on a new system of partitions that weave throughout the floorplate, made with a translucent textile membrane. The membrane was developed in coordination with Montreal firm Sollertia, founded by one of the Cirque du Soleil’s earliest collaborators.

For visitors arriving at the reinvented Biodome, the renewed spaces have an almost magical effect. The lobby, adorned with a minimalist reception desk and sparse bespoke furniture, sets the stage. Tall, sinuous architectural membranes frame a passageway leading visitors to the central atrium. Everything is set in dreamscape white. KANVA’s project, more about sensorial experience than scientific information, opens up the public areas to the skylit vault and creates an almost meditative space.

For visitors arriving at the reinvented Biodome, the renewed spaces have an almost magical effect. The lobby, adorned with a minimalist reception desk and sparse bespoke furniture, sets the stage. Tall, sinuous architectural membranes frame a passageway leading visitors to the central atrium. Everything is set in dreamscape white. KANVA’s project, more about sensorial experience than scientific information, opens up the public areas to the skylit vault and creates an almost meditative space.

Wayfinding is mostly intuitive, with formal graphics reduced to an absolute minimum. The signage indicating the way into the various ecosystems is barely noticeable. Information on the exhibits was moved out of the space, to be accessed through a cell phone application. The digital portal is extremely well designed and informative, albeit somewhat distracting from the animals on view, and not suited to all visitors.

From the central agora, people can choose which ecosystem they want to visit—a change from the earlier layout, where visitors were encouraged to go through the four zones in sequence. The Tropical Rainforest and the Laurentian Maple Forest are the two most spectacular ecosystems in terms of vegetation. However, the subantarctic penguin community remains one of the Biodome’s strongest attractions.

A novelty introduced by KANVA was the transformation of the Subpolar Regions access into an ice-lined tunnel, preparing visitors for the colder temperatures ahead. The exhibit itself, where the subantarctic and subarctic basins sit barely a metre from each other, is less convincing. Fortunately, the charming antics of southern penguins and northern puffins make up for the slight feeling of unease at seeing the two poles brought so close together.

A new mezzanine

One of the new elements introduced by the architectural team is an upper mezzanine, which serves as a rest area for periodic breaks and as the culminating point of a visit. It can be reached directly through stairs from two ecosystems, or by way of a glass-enclosed elevator from the central node. This pristinely designed area is capped by the humbling presence of Taillibert’s skylights. From up above, one gets a bird’s-eye view of the Laurentian Maple Forest, the Gulf of St. Lawrence area, and the enclosed Tropical Rainforest, which resonates with the sounds of chattering parrots.

Also on the mezzanine is a bright yellow interactive exhibit for children, which sits alongside the complex electrical and mechanical systems essential to the workings of the Biodome. As stressed by KANVA principal Rami Bebawi: “We wanted to reveal the mechanics of the Biodome, so that people would understand how complex the balance of life is.”

In an institution dedicated to raising awareness on environmental issues, the building’s energy sourcing has been an ongoing concern, and a geothermal system was installed in 2010. KANVA was also able to tap into a pre-existing heat pump system, which transfers waste energy from cooling the polar regions to keep the rainforest at tropical temperatures.

Back on the entry level, a corridor circling the building leads to the museum shop and cafeteria, adjacent to a second entry point—which is even more stunning than the main entrance, since it is visible from a distance. The membrane walls lining the peripheral corridor display an amazing formal versatility, made possible through the material’s unusual qualities. The only rooms that are perhaps less than optimal in the new configuration are the relocated administrative offices, which may not be sufficiently sound-proofed by the membrane walls.

The renewed Biodome opened in January 2021, in the midst of a global pandemic and an accelerating climate crisis. As visitors return to Montreal and to the Biodome, one wonders whether Pierre Bourque’s “rallying call of hope” will take a more urgent meaning, and be successful in truly raising awareness of the planet’s increasingly vulnerable ecosystems. For this visitor and Montreal resident, the new Biodome is truly inspiring and speaks of architectural beauty in a way few architects dare to—or are able to—achieve.

That success, however, goes beyond the considerable accomplishments of KANVA and Neuf’s present work. It owes much to the poetic audacity of an ill-understood Roger Taillibert, architect of the 1976 Velodrome. Equally audacious was the idea of transforming an underutilized Olympic building into a pioneering “living museum” with a mission in 1992. The creation of the Biodome was made possible by teams of young, enthusiastic, scientists working side by side with equally enthusiastic architects and engineers.

Building on this groundwork, KANVA was able to go one step further, infusing the Biodome with a dream-like quality. Beyond the need to address the degradation of the natural world, the architects’ intervention speaks to another urgent need: that of surrounding oneself with calm and beauty.

Odile Hénault, former publisher of the architectural magazine section a, has been documenting architecture in Quebec and Canada for decades. She is particularly interested in projects resulting from architectural competitions, a system now widely accepted in Quebec.

CLIENT Space for Life | ARCHITECT TEAM KANVA—Rami Bebawi (MRAIC), Tudor Radulescu (MRAIC), Laurence Boutin-Laperrière, Laurianne Brodeur, Dale Byrns, Gabriel Caya, Eloise Ciesla, Haley Command, Julien Daly, Léon Dussault-Gagné, Andrea Hurtarte, Olga Karpova, Brigitte Messier-Legendre, France Moreau, Andrei Nemes, Killian O’Connor, Claudia Pavilanis, Katrine Rivard, Dina Safonova, Minh-Giao Truong, Joyce Yam. NEUF—Azad Chichmanian, Marina Socolova, David Gilbert, Simon Bastien | STRUCTURAL NCK | MECHANICAL/ELECTRICAL Bouthillette Parizeau | INTERIORS KANVA | CONTRACTOR Groupe Unigesco | CODE/COST Groupe GLT+ | SPECS Atelier 6 | LIGHTING LightFactor | COLLABORATING EXHIBITION DESIGNER La bande à Paul | COLLABORATING SET DESIGNER Anick La Bissonnière | WAYFINDING Bélanger Design | LAND SURVEYOR Topo 3D | ACOUSTICS Soft dB | AREA 15,000 m2 | BUDGET $37.2 M | COMPLETION June 2020

View the article as it appeared in our June 2021 issue: