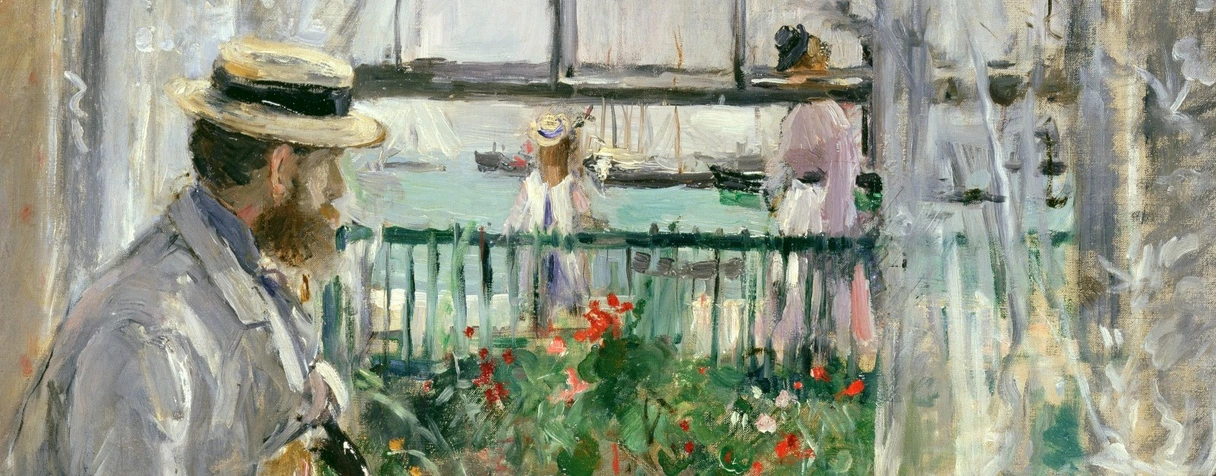

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895)

En Angleterre (Eugène Manet à l'île de Wight), 1875

Paris, musée Marmottan-Claude Monet

Fondation Denis et Annie Rouart, legs Annie Rouart, 1993

© Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / The Bridgeman Art Library / Service presse / DR

Berthe Morisot

Berthe Morisot

Autoportrait, 1885

Paris, Musée Marmottan-Claude Monet, fondation Denis et Annie Rouart

Legs Annie Rouart, 1993

© Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images / Service Presse

For the first time since its opening in 1986, the Musée d’Orsay is devoting an exhibition to a key figure in the Impressionist movement – Berthe Morisot (1841-1895). This is also the first solo show featuring this artist staged by a national museum since the retrospective at the Musée de l’Orangerie in 1941.

From a social background which her friend Renoir described as “austerely middle-class ” but receptive to the arts, Berthe Morisot displayed an early taste for independence reflected in her career in avant-garde movements, and in a painting style which marked her out as one of the most innovative Impressionist artists.

She took part in all of the group’s exhibitions, except in 1879.

She worked right up to her untimely death in 1895, leaving behind some four hundred paintings.

This exhibition aims to highlight a shift in how we look at Morisot, by suggesting and inspiring new approaches, while dispelling the clichés about “feminine’s painting” which are still associated with her work.

It focuses on a key aspect of her art: figure painting and portraiture. For Morisot, portraits and figure paintings capture the scenes of modern life.

They are characterised by what the recently deceased eminent art historian Linda Nochlin referred to as “stimulating ambiguities”. These are expressed in her models, in the choice and arrangement of spaces, and in her bold and energetic technique, which is allusive rather than descriptive.

Almost half of the paintings assembled here come from private collections and some have not been seen in France for over one hundred years.

The chronological and thematic presentation encourages visitors to consider some of the subjects depicted (fashion, women’s toilette, and work) which reflect not only the status of women in the 19th century, but also Morisot’s unique technique (outdoor painting, interiors, the importance of liminal spaces such as windows, and the issue of completion).

Her paintings explore modern identity, which she depicts as a fragile balance, in a register which is simultaneously peaceful and restless, luminous and mysterious, challenging and poetic.

Painting modern life

Painting modern life

Jeune femme à sa fenêtre (Portrait de Mme Pontillon), 1869

Washington, National Gallery of Art

Legs de Mme Ailsa Mellon Bruce, 1970

© Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

“I will only achieve [my independence] if I persevere and declare my intention to emancipate myself,” wrote Berthe Morisot in 1871.

For a woman from her social background, the first step towards liberating herself was a statement of her ambition to become a professional painter. In 1864, she therefore began to exhibit at the official Salon, which was an annual event at that time.

At the invitation of Edgar Degas, but against the advice of her friends Édouard Manet and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, she also decided to present her work at what would become the first Impressionist Exhibition in 1874.

The early 1870s were a crucial period for Morisot and she made figures the cornerstone of her work.

Her preferred model was her sister and painting companion Edma, who posed both indoors and outdoors.

Portrait de Madame Edma Pontillon, née Edma Morisot, soeur de l'artiste, en 1871

Musée d'Orsay

Legs de Madame Pontillon, 1921

photo musée d'Orsay / rmn © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d?RTMOrsay) / Adrien Didierjean / DR

See the notice of the artwork

Berthe Morisot sought to paint her environment as it was.

In an 1876 text, considered to be a manifesto for Impressionism, novelist and critic Edmond Duranty situated the representation of the modern figure in an interior at the very heart of what he called “the new painting”: “Our lives take place in rooms or on the street.”

This is why the domestic sphere – rooted in the inferior and muchmaligned genre scene and considered a subject and space suitable for women – was now taken up by the Impressionists, notably Degas, Caillebotte, Cassatt, Morisot, Renoir, and Monet at the outset of his career.

Morisot’s figures, who are both present yet absorbed in their daydreams, bring a silent poetry and an element of mystery to these scenes of modern life.

“Figure painting outdoors”

“Figure painting outdoors”

Chasse aux papillons, en 1874

Musée d'Orsay

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

See the notice of the artwork

After admiring a painting by Bazille in 1869, an enthusiastic Morisot wrote to her sister: “There is a great deal of light and sunshine. He achieves what we have so often sought to do: figure painting in an outdoor painting [...].”

She incorporated outdoor painting into her training at an early stage. Plein air painting as a tool for gaining an understanding of nature had been on the academic curriculum since the late eighteenth century, and was also a feature of work by amateur and professional women painters.

In the mid-nineteenth century, painters saw an opportunity to offer a fresh perspective on nature, facilitating the transcription of immediate impressions freed from academic routines.

In the 1870s, Morisot therefore produced numerous figures painted in nature – working in the spaces accessible to a woman from her background: Paris from the Trocadéro hill, location of her family home, the coastal resorts of Petites Dalles and Fécamp, private gardens, and public parks.

La Lecture (L?RTMombrelle verte), 1873

Cleveland Museum of Art

Don du Hanna Fund, 1950

© The Cleveland Museum of Art

For Morisot, the outdoor world is tied to the representation of modern life.

Her nineteenth-century upper middle-class scenes certainly capture the artist’s daily existence, but they are also spaces for aesthetic experiments.

Her technique is lively; with graphic brushstrokes, she sets down the main features, and a few figures which are sometimes extremely pared back and reduced to schematic touches of colour.

Outside, constant variations in light challenge the artist to work swiftly and effectively to create an “impression” and keep up with a fleeting motif. However, Morisot undoubtedly completed in the studio paintings which she had begun outdoors.

Women at their toilette

Women at their toilette

Jeune femme se poudrant, en 1877

Musée d'Orsay

Legs Antonin Personnaz, 1937

photo musée d'Orsay / rmn © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / DR

See the notice of the artwork

Between 1876 and 1894, Berthe Morisot produced some twenty scenes of women at their toilette.

The paintings record the shift back to the private sphere of moments which had been public prior to the nineteenth century. The professional models in these paintings are engaged in a variety of activities.

In the nineteenth century, the ritual of a woman’s toilette was governed by a multitude of fashion conventions.

The models are shown in their undergarments, such as a chemise worn next to the skin, forming the base layer of clothing which respectable women were not supposed to reveal to their husbands.

Femme à sa toilette, 1875-1880

Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago

Stickney Fund, 1924

© Image Art Institute of Chicago

Aside from Nu de dos, between 1876 and 1883, the artist’s own bedroom was depicted.

Morisot’s paintings of intimate scenes set against the backdrop of her own private space were nevertheless exposed to the public gaze.

Morisot exhibited two paintings featuring this subject matter at the Impressionist Exhibition in 1876, and introduced this theme into the group’s exhibitions.

She subsequently continued to show and sell this type of painting.

The “beauty of a creature adorning herself”

The “beauty of a creature adorning herself”

Eté (Jeune femme près d'une fenêtre), 1879

Montpellier, musée Fabre

Don de M. et Mme Ernest Rouart (Julie Manet), 1907

© Photo Studio Thierry Jacob

The poet Jules Laforgue celebrated the aesthetic potential to be found by artists in fashion: “Is the beauty of a person in evening dress, with such an expressive face, not just as interesting, as solid, as human, and as natural as a Greek nude?”

For the Impressionists, fashion and modern attire were key elements of “new painting”. Fashion in Morisot’s paintings did not reflect the designs of leading couturiers; she painted elegant gowns, adapted by seamstresses or from dress shops, for young upper middle-class Parisian women who – like the artist herself perhaps – did not set trends so much as follow them.

In the late 1870s and early 1880s, Morisot’s models were more tightly framed and figures took on a whole new scale, becoming the main focus of the paintings.

She did not ask members of her family or circle of acquaintances to sit for her, but used professional models whose identity is not known, thus lending an aura of mystery to these young women.

Jeune femme en toilette de bal, en 1879

Musée d'Orsay

Acquisistion de Théodore Duret, 1894

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

See the notice of the artwork

Likewise, their gowns are suggested rather than described.

The collars, jabots, flowers, accessories, fabrics and fur of these modern outfits provide an opportunity to use a lively, allusive touch, quick brushstrokes, broken lines, scraping and reworking – a technique at odds with the grace of the subject.

These half-length portraits form a sort of series within Morisot’s work and she presented them at the Impressionist Exhibitions to critical acclaim.

One of these paintings – Young Woman in a Ball Gown was acquired for the Musée du Luxembourg during her lifetime.

Finished/Unfinished: “To capture some passing moments”

Finished/Unfinished: “To capture some passing moments”

Le lac du bois de Boulogne (Jour d'été), vers 1879

Londres, The National Gallery

Legs de Sir Hugh Lane, 1917

© National Gallery, London

The issue of completion in Berthe Morisot’s paintings permeates her entire oeuvre and is central to the wider debate around Impressionism.

Morisot certainly carries out the most radical experiments in this respect, in both interior and exterior scenes, particularly in the late 1870s.

In an attempt to create a sense of immediacy, she adopts increasingly rapid and sketchy brushwork so that figures and backgrounds merge in an all-over effect stripped of spatial reference points.

Outdoors, plants – and occasionally water – fill the entire background to the exclusion of the sky.

Morisot favours the technique of leaving the margins of the canvas sparsely painted or even blank; the brushstrokes become looser in the corners, and the artist sometimes lets the unprimed canvas come through. In the 1880s, a journalist dubbed her “the angel of the incomplete”.

In the case of Morisot, unlike the other Impressionists, this unfinished appearance was not always viewed by contemporary critics as an artistic choice, but rather as a typical sign of female timidity and indecision.

However, on closer inspection, this approach bears the stamp of determination and authority rather than uncertainty. The artist asserts herself as the sole arbiter of whether a painting is finished or not.

Hiver, 1880

Dallas Museum of Art

Don de la Fondation Meadows Incorporated, 1981

© Photo Dallas Museum of Art

This “unfinished” aspect lies at the heart of Morisot’s artistic practice and vision of the world.

The surface of the painting is mobile and dynamic, playing with elements which create imbalances.

Even more radically, Morisot leaves visible traces of the construction and progression of her work in the completed painting and exploits them visually.

It is as if this complex, energetic, assured, personal, spontaneous, and accomplished technique is charting a race against time, the aesthetic of a “work in the making”, thus introducing temporality into the static world of the painting.

The impression of speed also reflects an attempt on Morisot’s part to mirror and resist the passage of time.

Women at work

Women at work

Blanchisseuse (Paysanne étendant du linge), 1881

Copenhague, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

© Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Domestic servants, maids, and wet nurses were among Morisot’s favourite models.

Operating in the heart of the home, they constitute another element of the portrayal of intimacy in the artist’s work.

Their silent and invisible labour, confined to the private sphere, lacks the political or naturalist dimension of depictions of peasants and workers which proliferated at the Salon in the 1880s. Morisot confers dignity and poetry on them.

With Cassatt and Pissarro, she was the only Impressionist to regularly depict domestic staff going about their daily chores.

Although her daughter Julie, born in 1878, was often painted with tender empathy during her childhood by her mother – just like the sons of her artist friend Renoir – Morisot depicted her in the company of the maids who took care of her.

In these paintings, her mother is not acting as a mother, but painting women who are working, just like her.

Morisot’s painting is not critical of motherhood, but suggests at the very least that it is not the only path to fulfilment, nor the inevitable fate of women.

Although servants, maids and wet nurses form part both of her everyday existence and her portrayal of modern life, they also mirror the artist as a working woman, as is demonstrated by the eminent historian Linda Nochlin.

Although servants, maids and wet nurses form part both of her everyday existence and her portrayal of modern life, they also mirror the artist as a working woman, as is demonstrated by the eminent historian Linda Nochlin Self-portrait, the only example of a painting in which she depicted herself alone and – more specifically – working.

Windows and thresholds

Windows and thresholds

La Terrasse, 1874

Tokyo, Tokyo Fuji Art Museum

© 2017 Christie's Images Limited

On close examination, the spaces painted by Berthe Morisot are often thresholds, liminal spaces, or interiors open to the outdoors and connected to it.

Morisot is particularly fond of balconies, windows, verandas and conservatories, which were very popular features of domestic architecture in the second half of the nineteenth century.

She favours these undefined areas where exterior and interior meet, at a time when these spaces were gendered and associated with specific household uses and social rituals.

A number of historians have seen this as the expression of female confinement within the domestic sphere at a time when “respectable” women had limited access to public spaces, and the street was viewed from the protective cocoon of the home.

En Angleterre (Eugène Manet à l'île de Wight), 1875

Paris, musée Marmottan-Claude Monet

Fondation Denis et Annie Rouart, legs Annie Rouart, 1993

© Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / The Bridgeman Art Library / Service presse / DR

However, in the case of Morisot, interior and exterior intermingle and merge, and one becomes an extension of the other, notably in the suite of paintings of Bougival.

The luxuriant vegetation in the garden seems to invade the room and transform the background into a form of decorative surface.

For an Impressionist enamoured with interactions between the outdoor world and figures, windows, verandas and conservatories also provide a source of filtered natural light which is easier to work with than full daylight outdoors.

These “thresholds” lend themselves to complex, innovative and poetic configurations of space, which deprive the viewer of reference points. By assembling these elements, the artist can dispense entirely with the idea of description or narrative.

Lastly, these spatial devices and windows onto the outdoor world serve as a frame and introduce paintings within the painting, which are also metaphors for the act of seeing.

A studio of one’s own

A studio of one’s own

Jeune fille au lévrier (Julie Manet et sa levrette Laërte), 1893

Paris, musée Marmottan-Claude Monet, Fondation Denis et Annie Rouart

Legs Michel Monet, 1966

© Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images / Service Presse

The title of this section is a reference to the essay by British novelist Virginia Woolf, who stressed the importance for a woman of having “a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

Berthe Morisot did not always have a studio as such, but was able to carve out spaces for painting which featured in her work.

In 1883, she created a studio/living room in the house she and her husband had built on the rue de Villejust in Paris (now rue Paul Valéry).

The pink-hued walls and print rack can be seen in several compositions dating from the early 1890s. However, it is the interior as a whole which seems to be saturated with art and to have become its mirror.

Towards the end of her life, Morisot produced a number of compositions in which her daughter Julie, her nieces, or a few professional models play instruments, draw and paint.

This creative activity within her own creations is accentuated by the presence of paintings from Morisot’s own collection and photographs of her past.

This technique of pictures within a picture captures memories which anchor the past in the present. They blur temporal and spatial reference points. The figure becomes a medium for exploring melancholic ideas about the passage of time, and memory.

In the early 1890s, Berthe Morisot’s work begins to show affinities with Symbolism and challenges the very notion of real time and space.

Long, fluid brushstrokes of saturated colour make the figures dissolve into their surroundings. Morisot’s interiors can be assimilated to projections of inner life, the music played by the models, or their daydreams, and they become detached from reality : «Dreams are life – and dreams are truer than reality: in them we behave as our true selves – if we have a soul, it is there.”