Abstract

The personal diary of Sir Augustus d’Esté, born 1794 grandson of King George III of England, reveals a medical history strongly suggesting that Augustus suffered from multiple sclerosis (MS). It could well be the first record of a person having this disease. Charcot coined the term sclérose en plaques 20 years after the death of this patient in 1848. The onset of this man’s MS seems to have been in 1822 with bilateral optic neuritis, the disease gradually developing in the classic manner with bouts derived from different loci in the central nervous system and eventually a secondary progressive form with paraparesis, sphincter incontinence, urinary problems and impotence. In 1941, Firth highlighted the case of Augustus d’Esté and later wrote a description of the pathology including a discussion on the aetiology of MS. No previous medical records have given such a characteristic picture of MS as this.

Similar content being viewed by others

A young nobleman at the beginning of the nineteenth century

We owe the first documentation of multiple sclerosis (MS) to a descendent of the Estense family.

Augustus d’Esté was born in 1794, grandson to the Hannoverian King George III of England and cousin to Queen Victoria. His father was Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, the sixth son of King George III and descendent of the House of Este that reigned in Ferrara in Emilia Romagna, north-eastern Italy, for nearly three centuries until the end of the Renaissance period. It is interesting that the surname Este was attributed to Augustus Frederick and his sister Augusta Emma after the marriage of their parents was declared illegitimate thereby denying them Royal prerogative.

The history of the Este family in Italy goes back to 813 when Bonifacio of Este came to Italy with Charles the Great. His descendents received the title of Duke of Ferrara and they reigned until the end of sixteenth century. With expansionism, opportune alliances and marriages over a period of centuries, the history of the Este House of Ferrara goes back to Alberto Azzo, Signore of Este and Count of Lunigiana and his descendent, Guelfo IV of Este. His son Ernesto Augustus of Este, imperial Elector of Hannover, obtained possession of Carinthia, Austria, thereby establishing the Estense branch of the House of Hannover and Elector of the Holy Roman Empire. Ernest Augustus married Sofia, Princess of England. Their Son, George Louis ascended the throne of England as George the First and gave origin to the Royal Hannover Dynasty of the United Kingdom that still reigns and from which Augustus d’Esté was descendedFootnote 1 [1].

His mother Lady Augusta Murray was daughter to John the sixth Earl of Dunmore, and she did everything for her son to be able to partake in the extravagant lifestyle typical of the English aristocracy at that time. She made great efforts to obtain recognition of the prerogatives of her marriage for herself and for Augustus and Emma. Augustus studied at Harrow and went on to military college and a career in the army where he eventually became lieutenant colonel.

Augustus’ education and art of writing lies behind the detailed information regarding his illness, which today enables us to make the retrospective diagnosis of MS. A part of the diary is missing but even so the case history is so typical and distinct that there can be no doubt about the diagnosis [2–6].

Augustus d’Esté is portrayed in a watercolour miniature by Richard Cosway, court artist at that time, which is kept at the Victoria and Albert Museum and entitled “Portrait of an Unknown Boy” [1] (Fig. 1).

Augustus’ case history

This part of the diary relevant to the diagnosis of MS, begins in 1822 where, at the age of 28, August describes symptoms typical of optic neuritis. This is what he wrote of the events leading up to, and first few days of these symptoms:

1822: The death of Strowan. Effect upon my Eyes.

In the month of December 1822 I travelled from Ramsgate to the Highlands of Scotland for the purpose of passing some days with a Relation for whom I had the affection of a Son. On my arrival I found him dead. I attended his funeral: - there being many persons present I struggled violently not to weep, I was however unable to prevent myself from so doing: - Shortly after the funeral I was obliged to have my letters read to me, and their answers written for me as my eyes were so attacked that when fixed upon minute objects indistinctness of vision was the consequence. Until I attempted to read, or to cut my pen, I was not aware of my Eyes being in the least attacked. Soon after, I went to Ireland, and without anything having been done to my Eyes, they completely recovered their strength and distinctness of vision…

Years later, symptoms derived from areas of the nervous system involving motor function and sensibility appeared:

17 October 1827.

To my surprise (in Venice) I one day found a torpor or indistinctness of feeling about the Temple of my left Eye. At Florence I began to suffer from a confusion of sight: - about the 6th November the malady increased to the extent of my seeing all objects double. Each eye had its separate visions. — Dr. Kissock supposed bile to be the cause: I was twice blooded from the temple by leeches; — purges were administered; One Vomit, and I twice lost blood from the arm: one of the times it was with difficulty that the blood was obtained. — The malady in my Eyes abated, I again saw all objects naturally in their single state. I was able to go out and walk. Now a new disease began to show itself: every day I found gradually (by slow degrees) my strength leaving me. — A torpor or numbness and want of sensation became apparent about the end of my Back-bone and the Perinaeum. At length about the 4th of December my strength of legs had quite left me… I remained in this extreme state of weakness for about 21 days… the problem with my eyes receded, and I recovered the vision of each object in its single state in the normal manner. I was once more able to go out and take a walk…”.

It was not long before Sir Augustus could no longer go hunting or dance at balls. By 1828 he had difficulty in managing uneven surfaces and steps, and he continued to describe painful sensations and fatigue [2]. Even so he continued his career in the army until a urine tract infection put a stop to it. He subsequently developed constipation and describes a period of anal incontinence. The diary also reveals that while on holiday in Ramsgate he developed impotence. Thereafter followed many remedy trips to various spas around Europe, medical consultations, prescriptions and treatments of various sorts. Such treatments included “electrification” in 1830, physical exercises, and the use of “Tincture of Cantharidae” from 1840 until 1846 during the final period of his life [2]. (Cantaridine is an acid which is extracted from the Spanish fly, Lytta vesicatoria, and is still used as aphrodisiac remedy).

Parts of the diary are missing but in the studies made by Granieri [1] and Firth [2] it was found that Sir Augustus also suffered from imbalance, ataxia and bouts of numbness below the waist. He also suffered muscle spasm at night. In 1843, apart from all other problems, he suffered an acute attack of giddiness and lack of coordination. He needed a stick to get around but with time he slowly recovered from these symptoms. Soon thereafter the illness developed into a slowly progressive form with overlapping bouts that included loss of power in the arms. See Fig. 2. Towards the end he became confined to a wheelchair, and in 1848 he died at the age of 54, unmarried and without offspring.

The disease course of Augustus d’Esté in graphical form by Professor E. Granieri. The y-axis shows disability score, EDSS expanded disability status scale by Kurtzke [18]

He thus suffered a neurological illness that, to begin with, came in bouts, but with time became progressive and with multiple dysfunctions. Multiple sclerosis had not been described at that time so the disease was not known, though certain pathologic observations had previously focused on this state as described below.

The early history of MS

In 1844, Sir Augustus received the diagnosis paraplegia. His physician’s comment was “The disease is called Paraplegia and is either active or passive, functional or organic.” This is very interesting since the usual cause of paraplegia at that time was neurosyphilis, and it is significant that Sir Augustus was not given that diagnosis [4]. It was Romberg who in 1846 first described the neuropathology of tabes dorsalis [7]. But Sir Augustus’ first neurological symptom was obviously an optic neuritis and this presented early on in life.

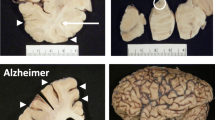

The concept MS was first described in 1868 by Jean Marie Charcot under the name La Sclérose en Plaques [8]. His greatest contribution was to identify diagnostic criteria, though these were later to be revised. The first neuropathology description was apparently made by one of those referred to by Charcot himself, Jean Cruveilhier (1791–1874, Professor of Pathology at the University of Paris), who published an atlas of pathology between 1829 and 1842 including clinical details that certainly described cases of MS [9]. Another early description of the pathology of a condition that was probably MS was published in an atlas by Sir Robert Carswell, Professor of Pathology at University College in London (see Fig. 3). This was printed by “Lithographers to the King” which indicates that it was published prior to 1837 when Queen Victoria ascended the throne. The detailed pathology picture describing both new and old lesions makes it most likely that the specimen was from a patient with MS [10]. The first clinical case of so-called spinal sclerosis was diagnosed 1849 in Germany [11]. Several years later a pupil of the same clinician published the neuropathological findings at autopsy [12]. These Germans pointed out the occurrence of bouts and included nystagmus as being a symptom.

Charcot identified the “triad” nystagmus, intention tremor and scanning, atactic speech, which he apparently observed in one of his housemaids [13]. He believed she suffered from tabes dorsalis but later autopsy revealed multiple areas of sclerosis in the CNS. He described the neuropathology including loss of myelin, remaining axis sheaths, glial proliferation, aggregations of fatty phagocytes, and thickening of small blood vessel walls [8]. He also described a connection between MS and previous illness such as typhoid fever, cholera, measles, and emotional stress. In spite of his interest in the disease, Charcot diagnosed only 34 cases of MS, 9 of whom were men [14].

MS risk factors in Augustus d’Esté’s case

The English physician Douglas Firth responsible for the Blind School Hospital in Leatherhead brought the case of Sir Augustus to light [2, 3]. The diary, partly facsimili, is presented in his interesting book “The case of Augustus d’Esté” (see Figs. 4, 5). He discussed the influence of external factors such as infection and psychological stress on the occurrence of MS. Augustus was variolated against smallpox and suffered infections such as “green faeces, colic and zoster”. Quite late on in life at 14 years of age he contracted measles which is interesting in the light of today’s discussion on the importance of late childhood infections in MS [15]. Augustus fell ill with optic neuritis shortly after suffering the loss and funeral of a dear friend, which is an example of how the illness is associated with extreme psychological stress. This has recently been shown in a Danish study that found over-representation of MS among people having suffered deep sorrow [16].

MS: a new disease or a new concept?

In an article published 1989, one of our authors (Fredrikson, 4) introduced the question: is MS a new disease or was it just that nosographic discovery of the disease was delayed because of the inability to detect, for example, cerebellar ataxia or nystagmus, and that the science of neuropathology was late in developing? Others claim that the disease is a new, previously unknown, disease since it is not mentioned in earlier medical textbooks, and both Carswell and d’Èste regarded the illness as “peculiar” and “a mysterious affliction”, respectively.

Early cases of MS include the first English case in 1873, the first Canadian in 1877 and the first American in 1878, i.e. a successive international spread. Of course, the reason can also be that the disease became internationally recognised. The suggestion that MS was caused by an infection was first made by Pierre Marie [17], an idea supported by many including the well-known neuro-epidemiologist Kurtzke. The beginning of the nineteenth century saw an increase in worldwide trade, to the Far East for example, and the beginning of the industrial revolution. Europe became a battlefield and thousands of soldiers were transported over an enormous area. With this in mind it is reasonable to postulate the appearance of a new infectious agent around 1830 somewhat akin to the sudden appearance of HIV/AIDS around 1980. The conclusion of Fredrikson’s paper 20 years ago was that MS was not just a new concept but also a new disease appearing in the early 1800s. The hypothesis then was that a retrovirus caused MS, but this has not been shown to be the case and the search for the code revealing the secret of MS goes on.

Notes

In English the accent on the last letter é, Esté, allows a correct pronunciation of the Italian surname in English.

References

Granieri E (2006) La malattia di Augusto d’Este. A un discendente degli Estensi si deve la prima testimonianza sulla sclerosi multipla. Ferrara Voci di una Città 25:3539

Firth D (1941) The case of Augustus d’Estè (1794–1848): the first account of disseminated sclerosis. Proc R Soc Med 34:381–384

Firth D (1948) The case of Augustus d’Esté. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Fredrikson S, Kam-Hansen S (1989) The 150-year anniversary of multiple sclerosis: does its early history give an etiological clue? Perspect Biol Med 32(2):237–243

Compston A, Lassman H, McDonald I (2006) The story of multiple sclerosis. In: McAlpines multiple sclerosis, 4th edn. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, London

Landtblom AM, Granieri E, Fredrikson (2007) The first documented case of multiple sclerosis—Augustus d’Este. Läkartidningen (Swedish Phys J) 26–27:2009–2011

Romberg MH (1846) Lehrbuch der Nervenkrankheiten. Berlin

Charcot JM (1868) Histologie de la sclérose en plaques. Gaz. des hospitaux 41:554–555, 557–558, 566

Cruveilhier J (1829–1842) Anatomie pathologique du corps humain ou descriptions avec figures lithographiées et coloriées des diverses altérations morbides dont le corps humain est susceptible. Bailliere, Paris

Putnam TJ (1938) The centenary of multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol Psych 40:806–813

Frerich FT (1849) Ueber Hirnsklerose. Arch Ges Med 10:334–350

Valentiner W (1856) Ueber die Sklerose des Gehirns und Ruckenmarks. Dtsch Klein 8:147, 158, 167

Bourneville DM, Guerard L (1869) De la sclérose en plaques disséminées. Delahage, Paris

Sherwin AL (1957) Multiple sclerosis in historical perspective. McGill Med J 26:39–48

Granieri E, Casetta I (1997) Selected reviews on common childhood and adolescent infections and multiple sclerosis. Neurology Suppl:S42–S54

Li J, Johansen C, Brönnum-Hansen H, Stenager E, Koch-Henriksen N, Olsen J (2004) The risk of multiple sclerosis in bereaved parents: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Neurology 5:726–729

Marie P (1884) Sclérose en plaques et maladies infectieuses. Progr Med Paris 12:287–289, 305–307, 349–351, 365–366

Kurtzke JF (1983) Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 33:1444–1452

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Landtblom, AM., Fazio, P., Fredrikson, S. et al. The first case history of multiple sclerosis: Augustus d’Esté (1794–1848). Neurol Sci 31, 29–33 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-009-0161-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-009-0161-4