Arnold Rothstein's Murder Is Still Unsolved Nearly A Century Later

On November 4, 1928, Arnold Rothstein — gambler extraordinaire, money man for the mob, and political fixer, according to Britannica — stumbled out of the service entrance of a Midtown Manhattan hotel. He was bleeding profusely from a single bullet wound to the abdomen and could barely stand, according to The New York Times. When he died two days later, he took the name of his killer with him to the grave after refusing to reveal who shot him to the police and kicked off a murder mystery that continues to haunt New York City nearly 100 years later.

Besides Rothstein's uncooperativeness, the police investigation into the killing had a cavalcade of problems, including incompetent cops who let potential witnesses slip through their fingers. Detectives didn't bother to secure the personal papers of Rothstein, a man who allegedly had dirt on everyone from local politicians to Hollywood stars, and they ended up with a shaky case against the prime suspect, per The Mob Museum.

He Fixed The 1919 World Series

Arnold Rothstein was born January 17, 1882, on Manhattan's East Side to a Jewish middle-class family, per Biography. But he went his own way, drawn to the easy money and thrill of gambling. By age 20, he already had his own casino and soon branched out into legitimate ventures, such as real estate, as well as nefarious businesses like bootlegging, narcotics, and banking for the New York underworld, helping them expand internationally (via History).

Rothstein's most infamous handiwork — for which he was never convicted — was fixing the 1919 World Series between the Cincinnati Reds and the Chicago White Sox, per Biography. In what would become known as the Black Sox Scandal, one of Rothstein's associates paid off several White Sox players to throw the series, which led to several changes in Major League Baseball, including creating the position of commissioner. As great a gambler as Arnold Rothstein had become, like all gamblers, he ran into a losing streak, and it was the most likely cause of his demise.

The Park Central Hotel

Two months before someone shot Arnold Rothstein at the Park Central Hotel on 7th Avenue and 55th Street, Arnold Rothstein sat with several other world-class gamblers in a high-stakes card game in Manhattan, per The New York Times. Rothstein lost $340,000 that night (the equivalent of more than $5.8 million today), but when the game broke up, the gambler admitted he didn't have the cash to cover his losses. "I'll probably have to sell an apartment house to meet these," he told the other gamblers, according to The New York Times. "But I have this, and that will wipe out some of it." He then tossed $37,000 in cash on the table and told the players to divide it among themselves. The other gamblers accepted the down payment, but when they tried to collect the rest — $303,000 — Rothstein refused to pay. The gambler, himself known for being a cheat, believed the other players had rigged the game against him, according to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

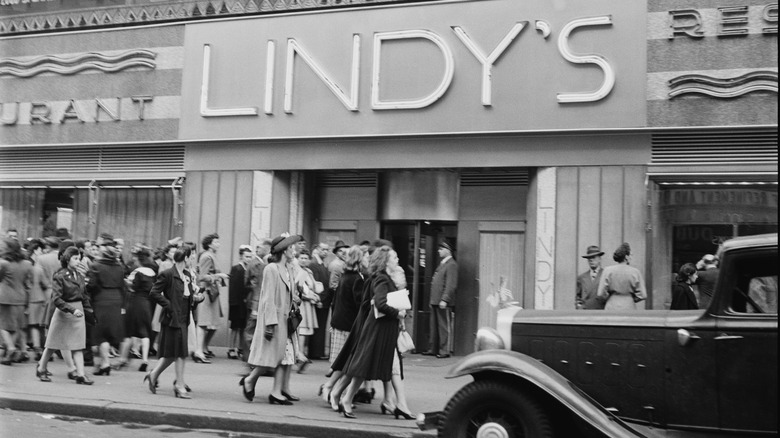

On the night of November 4, 1928, Rothstein was at his usual hangout, a restaurant named Lindy's, when he got a phone call around 10:15 p.m. After a brief conversation, he came back to his table, handed his pistol to a friend, and said (via The New York Times), "McManus wants me over at the Park Central." Less than an hour later, he was slowly dying after being shot with a .38 caliber slug.

Bungled Police Investigation

The police believed that room 349 was where the shooting had taken place. The room was empty except for two flasks — one still half filled with whisky — some glasses, and a topcoat with the name "McManus" stitched in it. George McManus was a friend of Arnold Rothstein and a fellow gambler who'd lost $51,000 in the same card game as Rothstein. The other gamblers had also hired McManus to collect their money from Rothstein, according to The New York Times.

But the investigation quickly went off the rails. Detectives couldn't prove Rothstein had even been inside room 349 that night, per The Mob Museum. The room had been rented under the name "George Richards," and there was nothing else solid connecting McManus to the hotel room besides his coat and statements that were later repudiated, per The New York Times. A March 31, 1929 article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle — written by Thomas Rice, a member of the New York State Crime Commission — tore into District Attorney Joab Banton and NYPD detectives for how they handled the case. Rice was shocked that the police hadn't bothered to secure Rothstein's personal records for several months, especially considering the gambler's known underworld connections, among other concerns.

Arnold Rothstein's Friends and Enemies

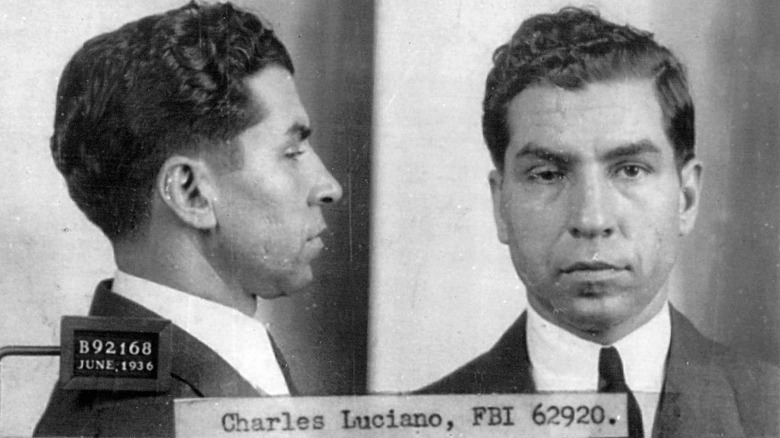

The list of potential enemies didn't just include the gamblers Arnold Rothstein had stiffed. He had nearly as many enemies as friends, and the "latter" numbered in "the thousands," The New York Times reported. Besides having cops and judges on his payroll, Rothstein also employed well-known gangsters, including Charles "Lucky" Luciano, Jack "Legs" Diamond, and Meyer Lansky, none of whom were known for their loyalty (per The Mob Museum). And then there were the many other mob associates Rothstein did business with, a veritable rogue's gallery of the New York underworld, including Louis "Lepke" Buchalter. Buchalter headed up Murder, Inc., the mob's assassination arm, per Britannica.

Another mysterious occurrence surrounding Rothstein's death involved his lawyer, Maurice Cantor, who got Rothstein to scrawl an "X" on a new will as the gambler lay dying in a hospital bed, per the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The new will gave Cantor five percent of Rothstein's estate, estimated at up to $3 million (about $51 million today), and increased how much Rothstein's mistress, Inez Norton, a former showgirl, received (via The Mob Museum). Whether the district attorney looked into any of the angles or not, he put his faith in the case against George McManus, no matter how shaky it was.

Rothstein's Alleged Killer Walks

George McManus went to trial in December 1929, the district attorney's case fell apart, and the court acquitted George McManus of the charges, according to The New York Times. Years later, McManus drunkenly confessed to a friend about killing Arnold Rothstein, according to David Pietrusza's 2003 biography, "Rothstein: The Life, Times and Murder of the Criminal Genius Who Fixed the 1919 World Series." "I did it, you know," McManus admitted, according to the book. "I was the one who gave it to Rothstein."

At least one person believes the shooting was nothing more than an accident. "I suspect [Arnold Rothstein] and McManus were arguing, the latter was drunk and he or his bodyguard pulled out a gun to play tough and it went off," Patrick Downey, author of "Gangster City: The History of the New York Underworld 1900-1935," told The Mob Museum. "If they wanted him dead, they would have given him one or two more in the head. Also, I don't think they would have summoned him to a popular hotel to kill him." Even so, because the court acquitted McManus of the crime, the case remains officially unsolved.