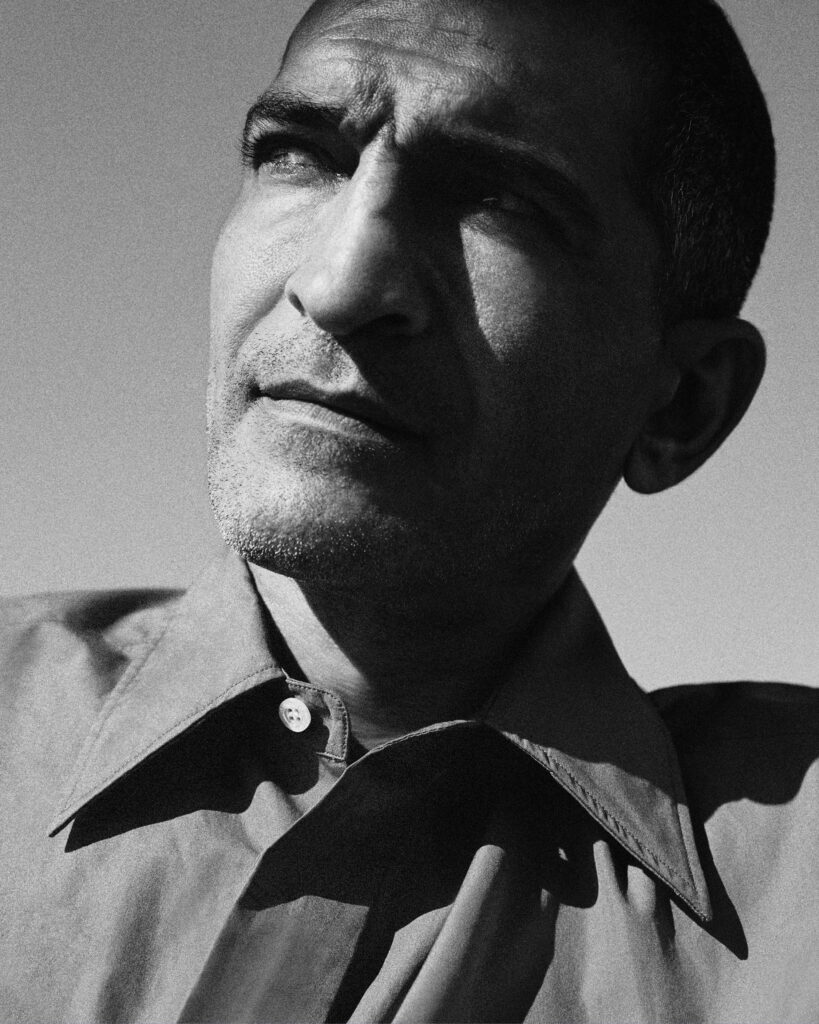

Four years ago, Amr Waked, Egypt’s greatest living actor, packed a single suitcase in the dead of night. He was leaving his country, his home, the market that had embraced him as its biggest star, the people that had followed him in the streets during a moment of reckoning, and the industry that had nearly devoured him.

While leaving was an act of hope, the belief that a better future could be found abroad, it was also the most terrified that Waked had ever been.

“I left with no intention to come back. It was a very scary move for me. I had so much at stake,” Waked tells us.

Make no mistake, Waked was leaving still on top. His most recent film, El-Qird Beyitkallem, released earlier that year, had been number one at the box office for six weeks, eclipsing the latest film from Mohamed Ramadan which experts had picked to easily surpass it. His detractors were not pleased.

“They had tried to stop me so many times before, so I was used to it at this point. It was always really devious and vicious stuff, asking journalists to print things that were not true. There were constant old school dirty tricks. But I didn’t stop. It gave me more fuel to continue. When that film hit number one and stayed there, that’s when they started getting really aggressive with me. The knives came out,” says Waked.

The fear for Waked, however, was not just a fear of what his enemies were capable of. More than anything, the fear was leaving behind a world in which he had grown too comfortable. In Barcelona, where he was headed, he couldn’t rest on fame and riches. There, the only person he would have to rely on was himself. It was time for Waked to finally grow into the person he’d always wanted to become—and personal growth is never easy.

“I had an assistant, a driver, a hairdresser—a second assistant. I had a whole damn entourage. I was walking around like a f***ing prince. Everything was just a clap away,” says Waked.

As we speak with Waked from his apartment in Barcelona, nothing is a clap away. He’s sitting in his office chair, and while his existence may not be Spartan, it’s not too far off. Behind him are a few chests of drawers from Ikea, a small photo framed and leaned against the bare, white walls.

There’s domestic clutter strewn about—a lint remover, an errant camera on top of the dresser, a yellow rag on a small table in the back corner. There are no maids to handle the mundane tasks—those are left to him. At one point as we speak, his wife comes in the room and wordlessly hands him a jar to open from off-camera—“sorry, husband duties”—and the phone rings here and there during out three-hour conversation. Only once does he answer it.

It’s a quick call.

“Brilliant. I’m ready, thanks,” says Waked to the person on the other end before hanging up.

He points at us. “I knew I liked you, William. You’re good luck.”

Who was it? Oh, just the producer of one of the most hotly anticipated action films of the next few years, and they have a major role for him. With only the title and director given to him, Waked was in.

If the simple life is this effective, what more could a man need?

“I love taking taxis, I love walking the streets. Going to the supermarket, spending an hour staring at the items on the shelves, checking for my yogurts without anybody pulling at me and saying ‘hey, can I take a picture?’ That is something really worth living for, to be a normal person, to walk the street and disappear.”

Since leaving Egypt behind, Waked has continued to flourish professionally. He’s starred in both seasons of Ramy Youssef’s award-winning hit show Ramy as Ramy’s father Farouk, with another anticipated season set to film in the coming months. He had a prominent role in the DC blockbuster Wonder Woman 1984, and has filmed an upcoming Terrence Malick picture called The Way of the Wind with Ben Kingsley and Mark Rylance.

He has a French superhero film coming out, along with a Spanish historical drama about Alhambra. He’s also presenting and producing an Al Jazeera series entitled Dahaleez, a show that explores philosophical questions and unsolved mysteries that had interested Waked himself, with a season two is already in the works ahead of its premiere.

Scheduling can be tricky, especially when he never makes it easy for himself. With Ramy, for example, he was sitting in the make-up chair on the first day when he realized he didn’t look fatherly enough. He quickly made a rather drastic decision—he would shave the top of his head to appear balding.

“I decided that on the spot. I sat there staring in the mirror, and I said, ‘Hey Ramy, what would you think of your dad was bald?’ He said, ‘What are you talking about, my dad is bald.’ I said ‘f***, I should be bald then. And I shaved it. Now Ican’t shoot anything for two months after we wrap while I wait for my hair to grow back,” says Waked.

When we ask why he doesn’t just use a bald cap, he immediately dismisses it.

“I’m a natural kind of guy,” says Waked.

There’s many reasons that, even as its biggest star, Waked never really fit in with the Egyptian film industry. For one, he had no interest in being a star, only reveling in the acting itself. It’s the transformations he delights in, the exploration, the honing of his craft. Even now, it’s something he never feels he’s quite mastered.

When he arrived in Barcelona, the first thing that Waked did was sign up for an acting workshop, shedding any lingering movie-star ego to work with non-professional Spanish actors who didn’t even know they were scene partners with one of the Arab world’s biggest stars. He, on the other hand, reveled in it, feeling transported back to the moment he first fell in love with the artform back in Egypt.

Waked was then 17 years old, and the love overtook him on the very first day that he ever stepped foot in a theater. He had needed a ride home, and found a guy from his neighbourhood who could take him on one condition—they would need to make a pitstop.

“He said, ‘sure I can take you, but can you wait for me while I do my audition?’

I begrudgingly said okay and walked into the theatre to wait for him. I said to myself, what is this? How haven’t I been inside one of these before? I was immediately obsessed with this place, by the negative space, this stage where everything shines. I felt sort of very strange power inside me saying ‘you belong here. This is this is where you should keep going’.”

Even though he’d never acted a day in his life, Waked jumped out of his seat, ran to the back, found his friend as he was talking to the director and asked if he could try out too. After all, how hard could it be?

“It was disgusting. It was horrific. The most horrible experience in my life. I stuttered. I sweated. I was shaking. My voice was hidden in my throat. I was a miserable idiot. I didn’t understand what happened. Why was I experiencing this? Why can my friend do it no problem?”

Immediately discouraged, Waked left, planning never to return.

“A week later, my friend checked the call list. He told me, ‘You’re called back. Come check the list.’ I said, ‘wow, what? What an idiot director.’ Then I checked closer, and it turned out I was playing a corpse, with a sheet covering my face so you couldn’t even see it was me. I went to the director, saying ‘this is not what I signed up for!

I want to be an actor, not a lamp post!’ He told me that while I was very motivated, I needed to train before I could do that. I said, ‘alright, I won’t be the corpse, but can I be your assistant? Can I get you coffee? I just don’t want to leave this place’,” says Waked.

Waked ended up spending eight years in independent theater, which he considers the best time of his career.

“I was young, motivated and free,” he says.

The Egyptian film industry was not as welcoming. Not because he didn’t have the talent—far from it, he outshined every person he auditioned with. The issue, rather, was that he didn’t want to play by their rules, and he didn’t even bother learning who was going to be calling him, let alone kiss their brass rings. It was there that the tensions began, tensions that continued until he finally left Egypt.

“Very big people in the industry would call me and I wouldn’t even know they were big. They would say, ‘don’t you know who you’re talking to?’ I would say, ‘I don’t know, who?’”

Those calls, as you can guess, would rarely go well. In Egypt at the time, the big producers and studios wanted to make their own stars, so if you were up and coming, they wanted to sign you to a three-picture contract, as that way they had time to build you into the image they found most marketable and then reap the profits. Actors even had to sign on before they even found out what the movies would be. Waked didn’t want to do it.

“I really struggled to maintain my position at the beginning. I had no mentor, I had no capital to defend me. That just motivated me more and put me in a place where I had to work on myself so that they would acknowledge me without me having to take those deals. Eventually, it worked. It took more time, but it worked,” says Waked.

“I have always felt I had something missing. I always felt like I need to work on myself even more all my life. I’ve always been treated likeI’m an outsider. I’ve always been questioned. That continues to this day.”

The early years were harder on Waked than he would care to admit. Because he eschewed the big money multi-picture deals, Waked had to support himself by selling equities on the side at a brokerage firm by day, and then, when he finally mustered up the courage to quit, he had to take projects he wasn’t proud of just to make ends meet.

Even then, Waked was not looking for the biggest pay day, and even the bad projects were ones he was hoping would turn out better than they did.

“Overall, my motivation was not the money or the fame, it was always to work with people who know what they’re doing,” says Waked.

After finally scoring some hits as the early 2000s progressed, he got his wish to work with the best on a big international project in 2005—Syriana, starring George Clooney and Matt Damon.

It was a rare opportunity for a Middle Eastern actor to land a major Hollywood role, and he knew it. With all the film offered, it was working with George Clooney that he was most thrilled about, an actor who seemingly could do it all, working at the peak of his powers.

On the first day of filming, Waked walked into a café that had been set up for a scene, anxious to get started, nervous to meet the great George Clooney, not sure exactly who he should be talking to or why everyone was late to the set.

Within the first twenty minutes, he nearly lost the job completely.

As he waited, the only person sitting in the café was an overweight man with a big grey beard, and Waked sat down next to him. He didn’t say hello, instead asking rudely, ‘so, when are we going to get started? Can they hurry up?’ The man responded softly they may be starting soon.

Finally, the director walked in. After graciously saying hello to his new boss, Waked asked pointedly, “So, where’s George?”

The director looked confused.

“He said, ‘he’s right there.’ I looked and he was pointing to the guy next to me I had been talking to. It was George,” says Waked.

“I said, ‘oh, sh**. I’m very sorry, I really didn’t recognize you’. He had grown a beard and put on weight for the role, and I didn’t realize! He said, ‘Oh it’s cool.’ I realized then, he was actually smiling. I thought I might be fired, but he was happy. In his eyes, it meant he’d really transformed himself for the role. We then had lunch, and we became friends instantly. We’re still friends now. He’s quite a brilliant person, truly kind and generous,” says Waked.

“You know what? Forget about the movie, forget about that role. Forget about everything. It was that one day with George in that café that was one of the highlights of my career.”

Clooney, in addition to his acting and directing work has also long been a vocal activist, highlighting numerous global crises and advocating for change across the world. As Waked’s star grew, and as wary as he was of his own profile, he too decided that he had to use his platform for social concerns, becoming a leading voice during the Egyptian revolution that saw the removal of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak in 2011.

While many lowered their voices after the revolution and Egypt moved past the instability of the time, Waked kept his raised, remaining outspoken about many issues, believing he owed it to an audience who had come to believe in him. As time went on, his views grew more and more divisive, emboldening his detractors and contributing to his exit from Egypt, where he viewed things may be headed in darker directions were he to stay.

“For me, fame was a responsibility more than a blessing. Or perhaps, maybe more of a curse. Because when you’re famous, people give you their trust, and what do you do with their trust? And that’s what I did. I tried to keep the trust. And I got damaged by doing that, but I am happy, I still have their trust. With that, I’m complete. I’m not missing anything. They took me out of the market a few years ago, because I’m vocal. And I feel when I watch what’s happening now, I’m not missing out.”

In 2019, two years after he left, was sentenced to eight years in prison by an Egyptian military court in absentia for his controversial language, a decision he can only appeal if he is to return in person.

Overall, Waked stays positive about his disconnect from Egypt. In his mind, he is first and foremost a citizen of the world, and with a half-French son living not far from Barcelona over the border and a career that takes him across the world, he is where he is supposed to be, and where he can do the most good, where he can continue to grow as a person and an artist.

Early in our conversation, there was only positive sentiments about his present situation, focused on hope, and possibility, and practicality. Waked is a person who is fascinated by so much—not just his craft, but of humanity, of astronomy, of metaphysics, spirituality, decentralized financial systems and uncovering the truth behind conspiracy. He’s also found time to become a skilled musician, now getting to the point where he plays every instrument on every song he makes.

“I’ve released three tracks so far. I have an album I’m preparing with guitar, and it’s been working very well. For me it’s important to keep my music active, that’s an area that’s really important to me now,” says Waked.

Things are great in the world of Amr Waked. And that’s not masking the reality—he truly is in a good place, centered, open and kind, giddy and childlike about the possibilities of discovery that life holds and wizened and matured enough to handle them with grace and care.

Still, the more we talk, the more it’s clear that the wounds have not fully healed, that a disconnect from Egypt, a place he once thought would always be his home, does in some ways feel like a lost limb, or a walled off piece of his heart.

He stays connected to the culture, paying attention to the best of what is being produced, such as the excellent film Feathers by Egyptian director Omar El Zohairy which won an award at Cannes Film Festival in 2021. He keeps in touch with many, but still, he hopes someday that the wounds can be healed, because even as digital connection grows easier, it’s never the same.

“I’ll be honest, it is painful. What’s painful is that I love Egypt. I can’t see it, and that’s painful. That alone is painful. The people that I know, the people that I worked with, I can no longer see them. Yes, I can call them, but you lose the human bond. That is no longer there,” says Waked.

“The pain is also seeing everything that is wrong, and not being able to do anything about it. Seeing people that you love that are going downhill. Some people can’t even see it. I can see them suffering more as I see them try to express that they’re suffering less. And the frequency of people reaching out to me, strangers, asking for me to please help them has risen so high. Because of that, the main pain that I feel is the vicarious pain of others.”

He doesn’t want to focus on the ways that it affects him personally, but it’s clear that it does. With a renaissance of arthouse cinema in Egypt in full gear, Waked would love the opportunity to work with someone like El Zohairy, a genuine visionary, but also knows it’s impossible, believing that he is now painted with a scarlet letter.

“I’m missing out on working with Omar, but I’m telling you, I don’t want the responsibility of working with him and then having him going to jail after it. I don’t want to do this to people.”

Maybe it’s fate that brought Waked to where he is now. For most of his life, the actor has credited fate for most of the happenings of his life, the gifts and blows that he’s received. If it’s fate or not, that no longer interests him as much. He’s got a new way forward.

“The best thing that happened last four years is that I worked on myself. I have transitioned, I really have. I took this moment to look back and see where I am, and anywhere I want to be. I started working on that, and it’s the first time I do this in my life,” says Waked.

“I’ve always been subject to what happens to me. I’ve always been a fate person. Now, I’m a destiny person. I make a choice. There’s is a big difference in how life treats you and how you treat life. What if that’s the only difference between fate and destiny—what you choose? You choose your destiny. Destiny is an outcome of your choices. Fate is an outcome regardless of your choices. And I don’t want that. I want destiny.”

Words by William Mullally

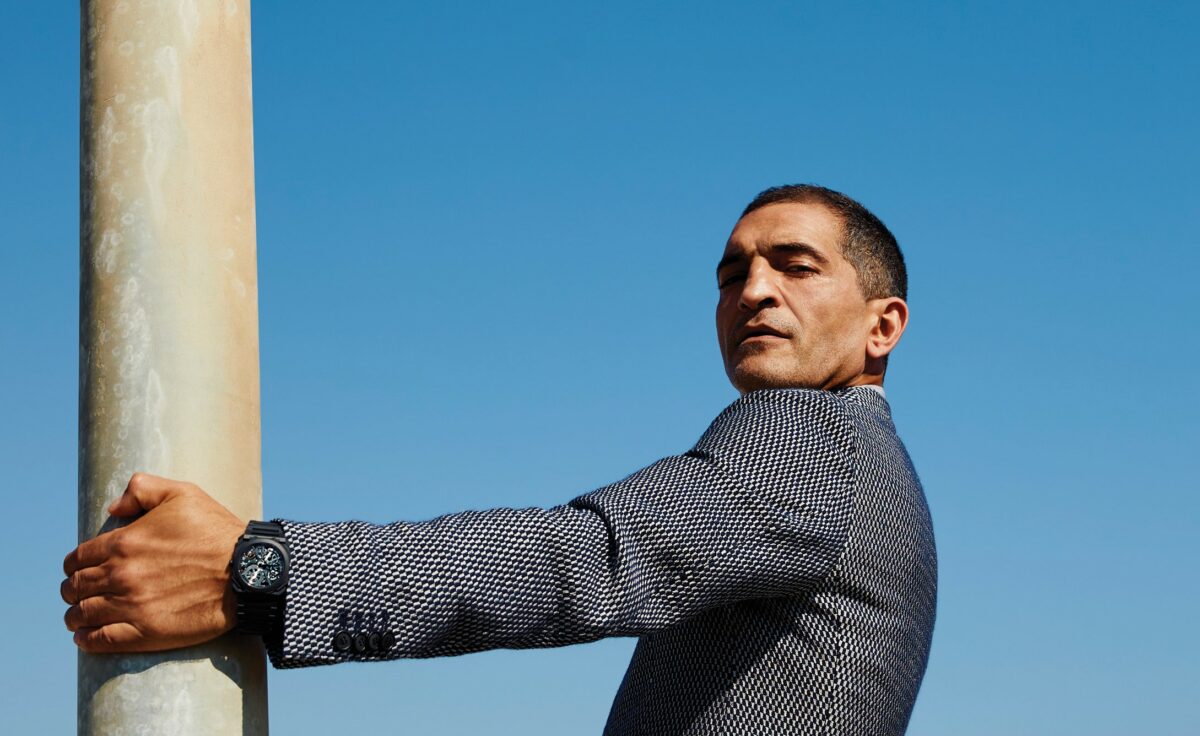

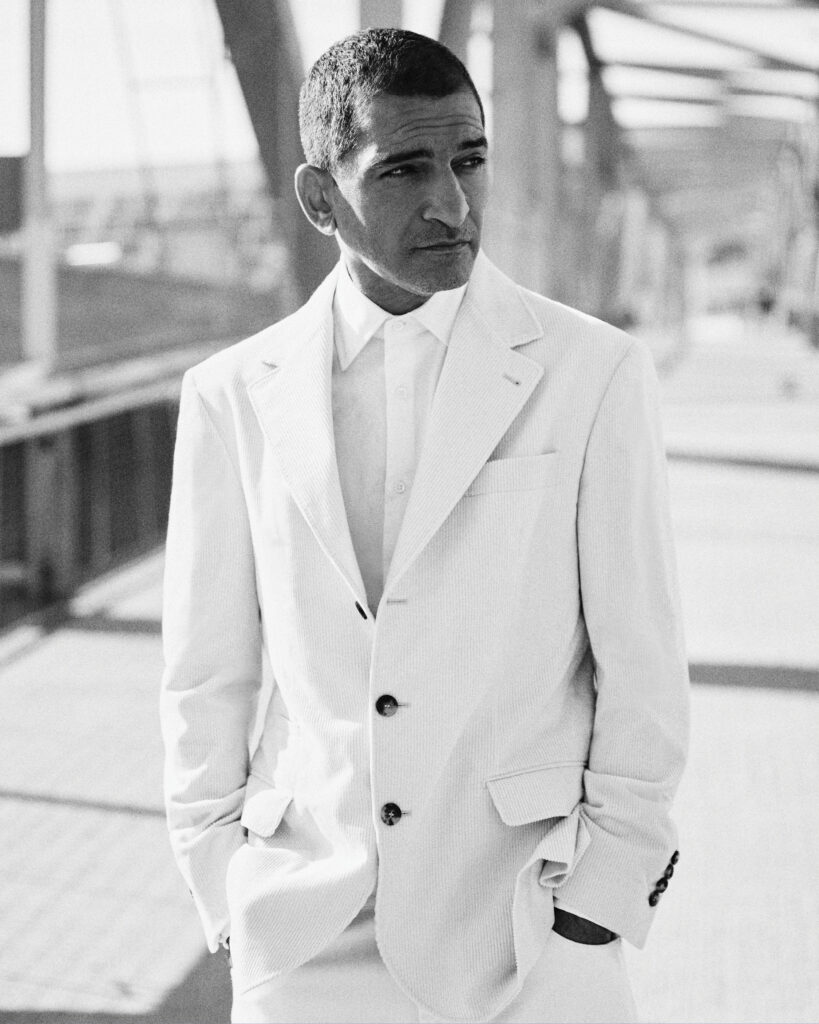

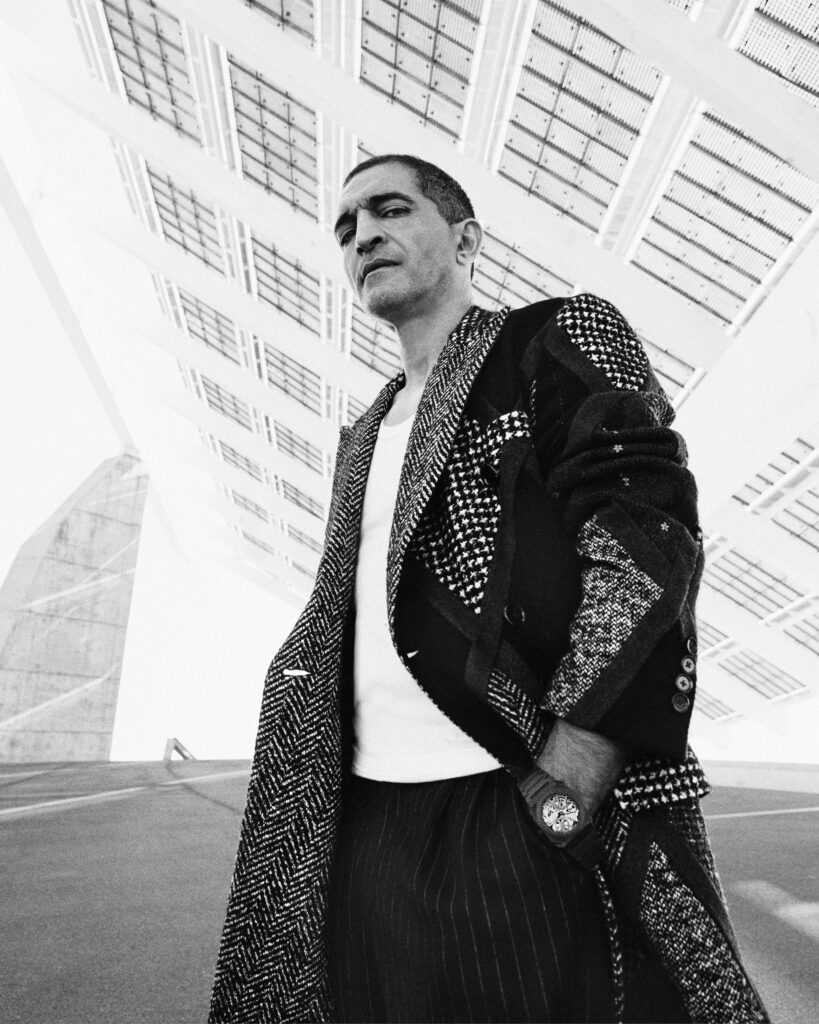

Photography by Vladimir Marti

Styling by Anna Castan