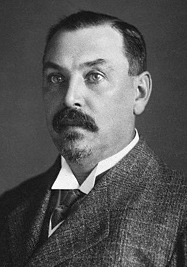

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner

Last updatedThe Viscount Milner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Secretary of State for the Colonies | |

| In office 10 January 1919 –13 February 1921 | |

| Preceded by | Walter Long |

| Succeeded by | Winston Churchill |

| Secretary of State for War | |

| In office 18 April 1918 –10 January 1919 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | Edward Stanley,17th Earl of Derby |

| Succeeded by | Winston Churchill |

| 1st Governor of the Transvaal and Orange River Colony | |

| In office 23 June 1902 –1 April 1905 | |

| Monarch | Edward VII |

| Preceded by | Himself as Administrator of the Transvaal and Orange River Colony |

| Succeeded by | William Palmer,2nd Earl of Selborne |

| Administrator of the Transvaal and the Orange River Colony | |

| In office 4 January 1901 –23 June 1902 | |

| Monarchs | Queen Victoria Edward VII |

| Lieutenant | Hamilton John Goold-Adams |

| Preceded by | Office Established Christiaan de Wet As State President of the Orange Free State (31 May 1902) Schalk Willem Burger As President of the South African Republic (31 May 1902) |

| Succeeded by | Himself As Governor of the Transvaal and Orange River Colony |

| Governor of the Cape Colony and High Commissioner for Southern Africa | |

| In office 5 May 1897 –6 March 1901 | |

| Monarchs | Queen Victoria Edward VII |

| Prime Minister | John Gordon Sprigg William Schreiner John Gordon Sprigg |

| Preceded by | Sir William Howley Goodenough |

| Succeeded by | Sir Walter Francis Hely-Hutchinson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Alfred Milner 23 March 1854 Gießen,Upper Hesse,Grand Duchy of Hesse |

| Died | 13 May 1925 (aged 71) Great Wigsell,East Sussex,England |

| Resting place | Saint Mary the Virgin Church,Salehurst,East Sussex,England |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse | Violet Milner |

| Alma mater | University of Tübingen King's College London Balliol College,Oxford |

| Occupation | Colonial administrator,statesman |

| Signature |  |

Alfred Milner,1st Viscount Milner, KG , GCB , GCMG , PC (23 March 1854 –13 May 1925) was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played a very important role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-1890s and early 1920s. From December 1916 to November 1918,he was one of the most important members of Prime Minister David Lloyd George's War cabinet.

Contents

- Early life and education

- Journalism,politics and service in Egypt

- In Southern Africa

- Milner Schools

- Protection for Uitlanders in Transvaal

- Second Boer War

- Peace

- Censure motion

- Businessman

- First World War

- Politics

- Wartime minister

- The Doullens Conference

- Postwar

- The peace treaty

- The treaty signing

- Last years

- Death

- Depictions

- Credo

- Evaluation

- Honours

- Works

- See also

- References

- Notes

- Citations

- Bibliography

- Further reading

- External links

Early life and education

Milner had partial German ancestry. His German paternal grandmother married an Englishman who settled in the Grand Duchy of Hesse. Their son,Charles Milner,who was educated in Hesse and England,established himself as a physician with a practice in London and later became Reader in English at University of Tübingen in the Kingdom of Württemberg. His wife was a daughter of Major General John Ready,a former Lieutenant Governor of Prince Edward Island and later the Isle of Man. Their only son,Alfred Milner,was born in the Hessian town of Giessen and educated first at Tübingen,then at King's College School and from 1872 to 1876 as a scholar of Balliol College,Oxford,studying under the classicist theologian Benjamin Jowett. Having won the Hertford,Craven,Eldon and Derby scholarships,he graduated in 1877 with a first class in classics and was elected to a fellowship at New College,leaving,however,for London in 1879. [1] At Oxford he formed a close friendship with the young economic historian Arnold Toynbee. He wrote a paper in support of his theories of social work and,in 1895,twelve years after Toynbee's death at the age of 30,penning a tribute,Arnold Toynbee:a Reminiscence. [2]

Journalism,politics and service in Egypt

Although authorised to practise law after being called to the bar at the Inner Temple in 1881,he joined the staff of the Pall Mall Gazette under John Morley,becoming assistant editor to William Thomas Stead. In 1885,he abandoned journalism for a potential political career as the Liberal candidate for the Harrow division of Middlesex but lost in the general election. In 1886 Milner opposed Irish Home Rule and supported the breakaway Liberal Unionist Party. Holding the post of private secretary to George Goschen (also a Liberal Unionist),Milner rose in rank when,in 1887,Goschen became Chancellor of the Exchequer and,two years later,used his influence to have Milner appointed under-secretary of finance in Egypt. Milner remained in Egypt for four years,his period of office coinciding with the first great reforms,after the danger of bankruptcy had been avoided. Returning to England in 1892,he published England and Egypt [3] which,at once,became the authoritative account of the work done since the British occupation. Later that year,he received an appointment as chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue. In 1894 he was made CB and in 1895 KCB. [2]

In Southern Africa

Alfred Milner remained at the Board of Inland Revenue until 1897. He was regarded as one of the clearest-headed and most judicious officials in the British service,and his position as a man of moderate Liberal Unionist views,who had been so closely associated with Goschen at the Treasury,Cromer in Egypt and Hicks-Beach (Lord St Aldwyn) and Sir William Vernon Harcourt while at the Inland Revenue,marked him as one in whom all parties might have confidence. The moment for testing his capacity in the highest degree had now come. [2]

In April,Lord Rosmead resigned his posts of High Commissioner for Southern Africa and Governor of Cape Colony. The situation resulting from the Jameson Raid was one of the greatest delicacy and difficulty,and Joseph Chamberlain,now Colonial Secretary,selected Milner as Lord Rosmead's successor. The choice was cordially approved by the leaders of the Liberal party and warmly recognised at a farewell dinner on 28 March 1897 presided over by the future prime minister H. H. Asquith. The appointment was avowedly made in order that an acceptable British statesman,in whom public confidence was reposed,might go to South Africa to consider all the circumstances and to formulate a policy which should combine the upholding of British interests with the attempt to deal justly with the Transvaal and Orange Free State governments. [4]

Milner reached the Cape in May 1897 and by August,after the difficulties with President Kruger over the Aliens' Law had been patched up,he was free to make himself personally acquainted with the country and peoples before deciding on the lines of policy to be adopted. Between August 1897 and May 1898 he travelled through Cape Colony,the Bechuanaland Protectorate,Rhodesia,and Basutoland. To better understand the point of view of the Cape Dutch and the burghers of the Transvaal and Orange Free State,Milner also during this period learned both Dutch and the South African "Taal" Afrikaans. He came to the conclusion that there could be no hope of peace and progress in South Africa while there remained the "permanent subjection of British to Dutch in one of the Republics". [5]

Milner was referring to the situation in the Transvaal where,in the aftermath of the discovery of gold,thousands of fortune seekers had flocked from all over Europe,but mostly Britain. This influx of foreigners,referred to as "Uitlanders",was received negatively in the republic,and Transvaal's President Kruger refused to give the "Uitlanders" the right to vote. The Afrikaner farmers,known as Boers,had established the Transvaal Republic after their Great Trek out of Cape Colony,which was done in order to live beyond the reach of the British colonial administration in South Africa. They had already successfully defended the Transvaal's annexation by the British Empire during the First Boer War,a conflict that had emboldened them and resulted in a peace treaty which,lacking a highly convincing pretext,made it very difficult for Britain to justify diplomatically another annexation of the Transvaal.[ citation needed ]

The Transvaal Republic stood in the way of Britain's "Cape to Cairo" ambitions,and Milner realised that,with the discovery of gold in the Transvaal,the balance of power in South Africa had shifted from Cape Town to Johannesburg. He feared that if the whole of South Africa were not quickly brought under British control,the newly wealthy Transvaal,controlled by Afrikaners,could unite with Cape Afrikaners and jeopardise the entire British position in South Africa.[ citation needed ] Milner also realised—as was shown by the triumphant re-election of Paul Kruger to the presidency of the Transvaal in February 1898—that the Pretoria government would never on its own initiative redress the grievances of the Uitlanders. [5] This gave Milner the pretext to use the "Uitlander" question to his advantage.

In a speech delivered on 3 March 1898 at Graaff Reinet,an Afrikaner Bond stronghold in the British Cape Colony,Milner outlined his determination to secure freedom and equality for British subjects in the Transvaal,and he urged the Boers to induce the Pretoria government to assimilate its institutions,and the temper and spirit of its administration,to those of the free communities of South Africa. The effect of this pronouncement was great and it alarmed the Afrikaners who,at this time,viewed with apprehension the virtual resumption by Cecil Rhodes of leadership of the Cape's Progressive (British) Party. [5]

Later in 1899,Milner met Violet Cecil,the wife of Major Lord Edward Cecil. Edward Cecil was commissioned to South Africa after serving in the Grenadier Guards. Milner and Violet began a secret affair that lasted until her departure for England in late 1900. She had a noticeable effect on his disposition,Milner himself wrote in his diary that he was feeling "very low indeed". Edward Cecil learned of this affair and pushed for a commission to Egypt after Violet pushed to return to South Africa. Milner later married Violet Cecil. [6]

Milner held hostile views towards the Afrikaners,and became the most prominent voice in the British government advocating war with the Boer republics to secure British control over the region. [6] After meeting Milner for the first time,Boer soldier (and future politician) Jan Smuts predicted that he would be "more dangerous than Rhodes" and would become "a second Bartle Frere". [7]

Milner Schools

In order to anglicise the Transvaal area during the Anglo-Boer war,Milner set out to influence British education in the area for the English-speaking populations. He founded a series of schools known as the "Milner Schools" in South Africa. These schools include modern-day Pretoria High School for Girls,Pretoria Boys High School,Jeppe High School for Boys,King Edward VII School (Johannesburg),Potchefstroom High School for Boys and Hamilton Primary School.

Although not all Afrikander Bond leaders liked Kruger,they were ready to support him whether or not he granted reforms,and contrived to make Milner's position untenable. His difficulties were increased when,at the general election in Cape Colony,the Bond obtained a majority. In October 1898,acting strictly in a constitutional manner,Milner called upon William Schreiner to form a ministry,though aware that such a ministry would be opposed to any direct intervention of Great Britain in the Transvaal. Convinced that the existing state of affairs,if continued,would end in the loss of South Africa by Britain,Milner visited England in November 1898.

He returned to Cape Colony in February 1899,fully assured of Joseph Chamberlain's support,though the government still clung to the hope that the moderate section of the Cape and Orange Free State Dutch would induce Kruger to give the vote to the Uitlanders. He found the situation more critical than when he had left,ten weeks previously. Johannesburg was in a ferment,while William Francis Butler,who acted as high commissioner in Milner's absence,had allowed the inference that he did not support Uitlander grievances. [5]

Protection for Uitlanders in Transvaal

On 4 May,Milner penned a memorable dispatch to the Colonial Office in which he insisted that the remedy for the unrest in the Transvaal was to strike at the root of the evil—the political impotence of the injured Uitlanders. "It may seem a paradox",he wrote,"but it is true that the only way for protecting our subjects is to help them to cease to be our subjects". The policy of leaving things alone only led from bad to worse,and "the case for intervention is overwhelming". Milner felt that only the enfranchisement of the Uitlanders in the Transvaal would give stability to the South African situation. He had not based his case against the Transvaal on the letter of the Conventions and regarded the employment of the word "suzerainty" merely as an "etymological question",but he realised keenly that the spectacle of thousands of British subjects in the Transvaal in the condition of "helots",as he expressed it,was undermining the prestige of Britain throughout South Africa,and he called for "some striking proof" of the intention of the British government not to be ousted from its predominant position. This dispatch was telegraphed to London,and was intended for immediate publication;but it was kept private for a time by the home government. [5]

Its tenor was known,however,to the leading politicians at the Cape,and at the insistence of Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr,a peace conference was held (31 May –5 June) at Bloemfontein between the high commissioner and Transvaal President Kruger. [5] Milner made three demands,which he knew could not be accepted by Kruger:the enactment by the Transvaal of a franchise law that would at once give the Uitlanders the vote,the use of English in the Transvaal parliament and for all laws of the parliament to be vetted and approved by the British Parliament. Realising the untenability of his position,Kruger left the meeting in tears.

Second Boer War

When the Second Boer War broke out in October 1899,Milner rendered the military authorities "unfailing support and wise counsels",being,in Lord Roberts's phrase "one whose courage never faltered". In February 1901,he was called upon to undertake the administration of the two Boer states,both now annexed to the British Empire,though the war was still in progress. He thereupon resigned the governorship of Cape Colony but retained the post of high commissioner. [5] During this period,numerous concentration camps were established to intern the Boer civilian population, [6] and as such the work of reconstructing the civil administration in the Transvaal and Orange River Colony could only be carried on to a limited extent while operations continued in the field. Milner therefore returned to England to spend a "hard-begged holiday," which was,however,mainly occupied in work at the Colonial Office. He reached London on 24 May 1901,had an audience with Edward VII on the same day,received the GCB [8] and was made a privy councillor, [9] and was raised to the peerage as Baron Milner,of St James's in the County of London and of Cape Town in the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope. [10] Speaking next day at a luncheon given in his honour,he answered critics who alleged that with more time and patience on the part of Britain,war might have been avoided,by asserting that what they were asked to "conciliate" was "panoplied hatred,insensate ambition,invincible ignorance". [5] In late July Milner received the Honorary Freedom of the City of London,and gave another speech in which he defended the government policy. [11]

Peace

Meanwhile,the diplomacy of 1899 and the conduct of the war had caused a great change in the attitude of the Liberal Party in England towards Lord Milner,whom a prominent Member of Parliament,Leonard Courtney,even characterised as "a lost mind". A violent agitation for his recall was organised,joined by the Liberal Party leader Henry Campbell-Bannerman. However,it was unsuccessful,and in August Milner returned to South Africa,plunging into the herculean task of remodelling the administration. [5] He bitterly fought Lord Kitchener,the Commander-in-Chief in South Africa,who ultimately won out. [12] However,Milner drafted the terms of surrender,signed in Pretoria on 31 May 1902. In recognition of his services he was,on 15 July 1902,made Viscount Milner,of Saint James's in the County of London and of Cape Town in the Cape Colony. [13] Around this time he became a member of the Coefficients dining club of social reformers set up in 1902 by the Fabian Society campaigners Sidney and Beatrice Webb.

On 21 June,immediately following the conclusion of signatory and ceremonial developments surrounding the end of hostilities,Milner published the Letters patent establishing the system of Crown colony government in the Transvaal and Orange River Colonies and changing his title of administrator to that of governor. [14] The reconstructive work necessary after the ravages of the war was enormous. He provided a steady revenue by the levying of a 10% tax on the annual net produce of the gold mines,and devoted special attention to the repatriation of the Boers,land settlement by British colonists,education,justice,the constabulary,and the development of railways. [5] At Milner's suggestion the British government sent Henry Birchenough a businessman and old friend of Milner's as special trade commissioner to South Africa with the task of preparing a Blue Book on trade prospects in the aftermath of the war. To aid him in his task,Milner recruited a team of gifted young lawyers and administrators,most of them Oxford graduates,who became known as "Milner's Kindergarten". [15]

While this work of reconstruction was in progress,domestic politics in England were convulsed by the tariff reform movement and Joseph Chamberlain's surprise resignation on 18 September 1903 due to health. Milner,who was then spending a brief holiday in Europe,was urged by Arthur Balfour to take the vacant post of Secretary of State for the Colonies. He declined the offer on 30 September 1903,considering it more important to complete his work in South Africa,where economic depression was becoming pronounced. With Milner promising to stay one final year in South Africa,Alfred Lyttelton was chosen for the Colonial Office. As of December 1903,Milner was back in Johannesburg,pondering the crisis in the gold-mining industry caused by the shortage of native labour. Reluctantly he agreed,with the assent of the home government,to a proposal by mineowners to import Chinese coolies,each on a three-year contract. The first batch of workers reached the Rand in June 1904. [16]

In the latter part of 1904 and the early months of 1905,Milner was engaged in the elaboration of a plan to provide the Transvaal with a system of representative government,a half-way house between Crown colony administration and that of self-government. Letters patent [17] providing for representative government were issued on 31 March 1905. [18]

For some time,he had been suffering health difficulties from the incessant strain of work,and determined a need to retire,leaving Pretoria on 2 April and sailing for Europe the following day. Speaking in Johannesburg on the eve of his departure,he recommended to all concerned the promotion of the material prosperity of the country and the treatment of Afrikaners and British on an absolute equality. Having referred to his share in the war,he added:"What I should prefer to be remembered by is a tremendous effort subsequent to the war not only to repair the ravages of that calamity but to re-start the colonies on a higher plane of civilization than they have ever previously attained". [18] In all,Lord Milner made three farewell speeches,in the Transvaal on 15 March 1905,in Pretoria on 22 March 1905,and in Johannesburg on 31 March 1905. The Times also paid a great tribute to Lord Milner's achievements on 4 April 1905.

He left South Africa while the economic crisis was still acute and at a time when the voice of the critic was audible everywhere but,in the words of the colonial secretary Alfred Lyttelton,he had in the eight eventful years of his administration laid deep and strong the foundation upon which a united South Africa would arise to become one of the great states of the empire. Upon returning home,his university bestowed upon him the honorary degree of DCL. [18]

Experience in South Africa had shown him that underlying the difficulties of the situation there was the wider problem of imperial unity. In his farewell speech at Johannesburg he concluded with a reference to the subject:"When we who call ourselves Imperialists talk of the British Empire,we think of a group of states bound,not in an alliance or alliances that can be made and unmade but in a permanent organic union. Of such a union the dominions of the sovereign as they exist to-day are only the raw material". That thesis he further developed in a magazine article written in view of the 1907 Imperial Conference in London. He advocated the creation of a permanent deliberative imperial council,favoured preferential trade relations between the United Kingdom and the other members of the empire and in later years took an active part in advocating the causes of tariff reform and Imperial Preference. [18]

Milner was the founder of The Round Table –A Quarterly Review of the Politics of the British Empire ,which helped to promote the cause of imperial federation in Britain. The journal was founded in part due to concerns of the lack of support for the expansion of the British Empire in Britain,and The Round Table sought to bring greater awareness of imperial issues to the British public. The introduction to the journal,first published in November 1910,reads:

It is a common complaint, both in Great Britain and in the Dominions, that it is well-nigh impossible to understand how things are going with the British Empire. People feel that they belong to an organism which is greater than the particular portion of the King's dominion where they happen to reside, but which has no government, no Parliament, no press even, to explain to them where its interests lie, or what its policy should be. Of speeches and writings about the Empire there is no end. But who has time to select what is worth reading from the multitude of newspapers and reviews? Most people have no access to the best among them, and such as have are haunted by the fear that what they read is coloured by some local party issue in which they have no concern. No one can travel through the Empire without being profoundly impressed by the ignorance which prevails in every part, not only about the affairs of the other parts, but about the fortunes of the whole.

The journal, still in publication, was renamed in 1966 The Round Table: Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs. [19]

Censure motion

On 20 March 1906, a motion censuring Lord Milner for an infraction of the Chinese labour ordinance, in not forbidding light corporal punishment of coolies for minor offenses in lieu of imprisonment, was moved by a Radical member of the House of Commons. [20] On behalf of the Liberal government an amendment was moved, stating that 'This House, while recording its condemnation of the flogging of Chinese coolies in breach of the law, desires, in the interests of peace and conciliation in South Africa, to refrain from passing censure upon individuals'. The amendment was carried by 355 votes to 135. As a result of this left-handed censure, a counter-demonstration was organised, led by Sir Bartle Frere, and a public address, signed by over 370,000 persons, was presented to Lord Milner expressing high appreciation of the services rendered by him in Africa to the Crown and empire. [18] The censure was made by William Byles, and amended by a young parliamentarian named Winston Churchill, who added:

Lord Milner has gone from South Africa, probably forever. The public service knows him no more. Having exercised great authority he now exercises no authority. Having held high employment he now has no employment. Having disposed of events which have shaped the course of history, he is now unable to deflect in the smallest degree the policy of the day. Having been for many years, or at least for many months, the arbiter of the fortunes of men who are 'rich beyond the dreams of avarice', he is today poor, and honourably poor. After twenty years of exhausting service under the Crown he is today a retired Civil Servant, without pension or gratuity of any kind whatever... Lord Milner has ceased to be a factor in public life.

The problem confronting South Africa after the Boer War was that it needed to rebuild. The country was devastated by war, its biggest natural resource were its gold mines, and reconstruction would have to come from within. The quickest and easiest way to rebuild would be with revenue from its gold mines, and labour was in short supply. The plan Lord Milner put into place he called, "Lift and Overspill". [21] This two phase process called for economic resources to be used to fill government coffers, and then for government spending and economic growth to be used to spread prosperity. The need for labour was essential if this plan was to work, and with help from Parliament, a Labour Ordinance [22] was passed to permit the advertising and importation of Chinese labourers to fill that task. The workers were hired, they were shipped to South Africa, they lived in work camps close to the mines, and after their three-year contracts expired, they were sent home. This was accepted practice in the British Empire, and in the United States as well, where Chinese coolies were imported to build the First transcontinental railroad. Problems that occurred related to a lack of amenities, confinement in the work area, and insubordination. The Chinese workers in South Africa were no exception. They were known to run away, and to strike for higher wages. Flogging was used to deal with insubordination, and whether he knew about it at the time or not, Lord Milner accepted full responsibility for what happened, and he said it was a bad practice.

Churchill, in the House of Commons on 22 February 1906, said the about the Chinese labour ordinance:

....it cannot in the opinion of His Majesty's Government be classified as slavery in the extreme acceptance of the word without some risk of terminological inexactitude .

Businessman

Having worked closely with Cecil Rhodes in South Africa, he was appointed a trustee to Rhodes' will, [23] upon Rhodes's death in March 1902.

Upon his return from South Africa, Milner occupied himself mainly with business interests in London, becoming chairman of the Rio Tinto Zinc mining company, though he remained active in the campaign for imperial free trade. In 1906 he became a director of the Joint Stock Bank, a precursor of the Midland Bank. In the period 1909 to 1911 he was a strong opponent of the People's Budget of David Lloyd George and the subsequent attempt of the Liberal government to curb the powers of the House of Lords.

First World War

Politics

From a letter published in The Times on 27 May 1915, Lord Milner was asked to head the National Service League during the First World War. As an advocacy group for conscription at a time when it did not exist (it did not come into effect until 1 January 1916), Milner pressed for universal conscription. [24] His strong position forced a meeting with the King at Windsor Castle on 28 August 1915. [25]

Known as, the Ginger group meetings, Lord Milner held small meetings at his home on 17 Great College Street to discuss the war. On 30 September 1915, Lloyd George, then Minister of Munitions, and an advocate of conscription, attended one of these meeting. The two established close relations. Lord Milner was also an outspoken critic of the Gallipoli campaign, speaking in the House of Lords on 14 October 1915 and 8 November 1915, and suggesting a withdrawal. Starting on 17 January 1916, the ginger group attendees (Henry Wilson, Lloyd George, Edward Carson, Waldorf Astor, and Philip Kerr among others), discussed the setup of a new, small war cabinet. Lord Milner, thinking that the Liberal led Asquith coalition ministry could be defeated, also envisioned a new political party composed of trade workers, called, the, National Democratic and Labour Party . Although weak on a social platform, the National Party emphasised imperial unity and citizen service. Empowered by the ginger group, the National Party got off to a slow start in 1916, running just one candidate, but it eventually ran 23 candidates in the 1918 election.

The need for a change in the administration of the war was summed up by Leo Amery who described the old cabinet as an, "assembling of twenty three gentlemen without any idea of what they were going to talk about, eventually dispersing for lunch without any idea of what they had really discussed or decided, and certainly without any recollection on either point three months later". [26]

Lord Milner's speech in the House of Lords on 19 April 1916 strengthened the new law conscripting married men, "making all men of military age liable of being called up to service until the war ends." [lower-alpha 1] With the sinking of the Hampshire on 5 June 1916, both The Times (8 June 1916) and the Morning Post supported Lord Milner's replacement of Lord Kitchener at the War Office, although the job of Secretary of State for War went to Lloyd George. Bonar Law then asked Lord Milner to head the Dardanelles Commission. [27] However, Milner had previously committed himself to supervising the government's three coal committees, at the request of Lord Robert Cecil. His report, which addressed coal production problems, was submitted on November 6. [28]

With the government's principal internal critic, Lloyd George, now occupied with the duties of Secretary of State for War, Lord Milner was now the government's most forceful critic outside of government, and behind the scenes. [29] The ginger group tried to convince members of the Asquith's coalition government to resign. With this, they had no luck. They then tried to take down the Asquith Coalition in a dual approach, with Lord Milner making speeches in the House of Lords, and Sir Edward Carson, who was Leader of the Opposition, making speeches in the House of Commons. The group knew nothing about the Conservative Leader Bonar Law, but both Milner and Carson had contacts with Lloyd George, the leading member of the cabinet, so they focused on him. On 2 December 1916, Lord Milner dined with Arthur Steel-Maitland, Chairman of the Conservative Party, where he was asked to draft a letter describing the war committee he envisioned. This letter was then sent to Bonar Law. [30]

The next day, Lloyd George met Prime Minister Asquith, and a reconciliation deal was thought to have been reached, one that would have created a small war committee headed by Lloyd George, but still reporting to Prime Minister Asquith. However, The Times published an editorial on 4 December 1916, "Reconstruction," critical of Asquith and announcing a reforming of the coalition government, and the enhanced position of Lloyd George. [31] Asquith blamed this news release on Lord Northcliffe (of The Times) and Lloyd George. He insisted that he himself must chair the war committee, causing Lloyd George to resign from the government. Asquith demanded the resignations of his ministers, with a view to reconstructing his government. After the leading Conservatives Lord Curzon, Lord Robert Cecil and Austen Chamberlain declined to serve under him again, he submitted his resignation as Prime Minister to the King on 6 December 1916. The King immediately asked Bonar Law to form a government, but he declined as Asquith refused to serve under him. The King then turned to David Lloyd George, who was up to the task, and who took office the same day.

On 8 December 1916, Lord Milner received a letter from Prime Minister Lloyd George, asking him to meet him, and to join the new war cabinet, which was to meet the next day at the War Office. Milner happily accepted. [32] Despite not heading any government department (in common with all the members of the war cabinet except Arthur Henderson), Lord Milner was paid a salary of £5,000 (£350,000 in 2020). [33] [34]

Wartime minister

Since Milner was the Briton who had the most experience in civil direction of a war, Lloyd George turned to him on 9 December 1916 [35] when he formed his national government. He was made a member of the five-person War Cabinet. As a Minister Without Portfolio, Milner's responsibilities varied according to the wishes of the Prime Minister. Per War Cabinet Secretary Maurice Hankey:

With the exception of Bonar Law, the members of the War Cabinet were all Ministers Without Portfolio. The theory was that they were to devote all their time and energy to the central direction of the British war effort, on which the whole of the energies of the nation were to be concentrated. To enable them to keep their minds on this central problem they were freed entirely from departmental and administrative responsibilities.

In addition to war matters, all domestic related issues pertaining to the war fell in his lap, such as negotiating contracts with miners, agriculture, and food rationing. Considering his background, as a former High Commissioner in South Africa, and a Tory intellectual leader, these other matters were not ideally suited for him[ citation needed ]. However, he remained one of Prime Minister Lloyd George's closest advisers throughout the war, second only to Bonar Law.

Upon conclusion of the first war cabinet meeting on 9 December 1916, which lasted seven hours, Lloyd George got along very well with Lord Milner. He told his press contact, George Riddell, "He picked out the most important points at once", and, "Milner and I stand for the same things. He is a poor man and so am I. He does not represent the landed or capitalist classes any more than I do. He is keen on social reform and so am I." [32] To fill in the Garden Suburb (junior positions at 11 Downing Street that assisted the war cabinet), Lloyd George turned to Lord Milner, who filled vacancies with capable men from his past: Leo Amery, Waldorf Astor, Lionel Curtis and Philip Kerr. It is this connection that gave rise to rumours in quarters of the liberal press of a sinister side to Lord Milner, with long lived rumours of behind the scenes, "Milnerite penetration" influencing crucial government decision making.[ citation needed ]

Following the death of Lord Kitchener aboard HMS Hampshire on 5 June 1916, on 20 January 1917 Milner led the British delegation (with Henry Wilson as chief military representative and including a banker and two munitions experts) on a mission to Russia aboard the Kildonan Castle. There were 51 delegates in all including French (led by Noël Édouard, vicomte de Curières de Castelnau) and Italians. The object of the mission, stressed at the second Chantilly Conference in December 1916, was to keep the Russians holding down at least the forces now opposite them, to boost Russian morale and see what equipment they needed with a view to coordinating attacks. [36] However, a feeling of doom prevailed over the meetings once it was discovered that Russia had huge equipment problems, and that Britain's ally operated way behind that of the west, which negated its manpower advantage. Instead of helping its ally, British assistance was reduced to intervening with a task force to prevent allied stockpiles from falling into the hands of revolutionaries at the port of Archangel. The official report in March [37] said that even if the Tsar was toppled—which in fact happened just 13 days after Milner's return—Russia would remain in the war and that they would solve their "administrative chaos". [38]

It was Milner's idea to create an Imperial War Cabinet, similar to that of the War Cabinet in London, which comprised the heads of government of Britain's dominions. [39] The Imperial War Cabinet was an extension of Lord Milner's imperial vision of Britain, whereby the Dominions (her major colonies) all had an equal say in the conduct of the running of the war. The problems of Imperial federation were encapsulated here, whereby if all of Britain's colonies were elevated to the same status as the mother country, her say was diluted by foreigners with different points of view. [40] In the closing days of the Imperial War Conference in 1917, the Imperial War Cabinet decided to postpone the writing of an Imperial Constitution until after the war.[ citation needed ] This was a task it never took up. [41]

Due to the U-boat campaign and the Kaiser's attempt to starve Britain in early 1917, Lord Milner assisted the Royal Agricultural Society in procuring 5,000 Fordson tractors for the ploughing and planting of grasslands, and communicated directly with Henry Ford by telegraph. [42] It is said that without the aid, Britain may not have met its food crisis.[ citation needed ]

Milner became Lloyd George's firefighter in many crises and one of the most powerful voices in the conduct of the war. He also gradually became disenchanted with the military leaders whose offensives generated large casualties for little apparent result, but who still enjoyed support from many politicians.[ citation needed ] He backed Lloyd George, who was even more disenchanted with the military, in successful moves to remove the civilian and military heads of the Army and Navy. First Sea Lord (professional head of the Navy) Admiral John Jellicoe had lost the confidence of the government over his reluctance to organize ships into convoys to reduce the threat from submarines. In July 1917 Sir Edward Carson was replaced as First Lord of the Admiralty (navy minister) by Eric Geddes (Carson was promoted to the war cabinet, only to resign over Irish Conscription early in 1918). Infamously, Admiral Jellicoe was finally dismissed on Christmas Eve, 1917. [43] General William Robertson was removed as Chief of the Imperial General Staff (head of the Army) early in 1918 due to his inability to agree to an allied command structure set up in Versailles, France. Milner himself replaced Edward Stanley, 17th Earl of Derby as Secretary of State for War (Army minister) in April 1918.

On at least one occasion the conservative Milner came to the aid of people from the other end of the political spectrum. He was an old family friend of Margaret Hobhouse, the mother of imprisoned peace activist Stephen Henry Hobhouse and was Stephen's proxy godfather. In 1917, when Margaret was working to get her son and other British conscientious objectors freed from prison, Milner discreetly helped, intervening with high government officials. As a result, in December 1917 more than 300 COs were released from prison on medical grounds. [44]

Milner was involved in every major policy decision taken by Prime Minister George's Government in the war, including the Flanders Offensive of 1917, which he initially opposed, along with Bonar Law and Lloyd George. Lloyd George spent much of 1917 proposing plans to send British troops and guns to Italy to assist in an Italian offensive (this did not happen in the end until reinforcements had to be sent after the Italian disaster at Caporetto in November). The War Cabinet did not insist on a halt to the Third Battle of Ypres offensive in 1917 when the initial targets were not reached and indeed spent little time discussing the matter—around this time the CIGS General Robertson sent Haig (CinC of British forces in France) a biting description of the members of the War Cabinet, who he said were all frightened of Lloyd George—he described Milner as "a tired and dispeptic old man". [45] By the end of the year Milner had become certain that a decisive victory on the Western Front was unlikely, writing to Lord Curzon (17 October) opposing the policy of "Hammer, Hammer, Hammer on the Western Front", and had become a convinced "Easterner", wanting more effort on other fronts. [45] [46] As an experienced member of the War Cabinet, Milner was a leading delegate at the November 1917 Rapallo Conference in Italy that created an Allied Supreme War Council. He also attended all subsequent follow up meetings in Versailles to coordinate the war.

Milner was also a chief author of the Balfour Declaration, [47] although it was issued in the name of Arthur Balfour. He was a highly outspoken critic of the Austro-Hungarian war in Serbia arguing that "there is more widespread desolation being caused there (than) we have been familiar with in the case of Belgium".[ citation needed ]

The Doullens Conference

On 21 March 1918 the Germans attacked. For the first three days of the offensive, the War Cabinet was uncertain of the seriousness of the threat. General Philippe Pétain was waiting and expecting the main assault to come in his sector of Compiègne, about 75 miles south of where it actually took place. Having secured victory on the Eastern Front in 1917, the Germans turned their attention to the Western Front in the winter of 1917-18 by moving their combat divisions in the east, by rail, to France. It was thought that Germany had in place over 200 divisions on the Western Front by the spring of 1918 (compared to France's 100, and England's 57). When the Germans struck on March 21, they concentrated their manpower and hit the allies at their weakest point, at the junction between the English and French lines. They were helped by a number of factors: 1) a recent redeployment of the B.E.F. to cover a 28-mile longer line on the front, 2) the lack of a central reserve of soldiers that the civilian leadership had ordered, but which the military had ignored, 3) the pre-deployment of British and French divisional reserves to the North and South of the line, opposite from where they were to be needed, in the middle, 4) the lack of an overall allied leader, which, in a time of crisis, caused the military leaders to look out for their own national interests, and not that of the whole, 5) the intense retraining of German infantry divisions into new forms of soldiers called, "stormtroopers", 6) dry weather that made otherwise swampy ground hard, 7) intense fog on the morning of the first two days of the assault, and 8) complete surprise.

The artillery barrage commenced at 4:45 am, it lasted four hours, and when it ended, the German infantry advanced through no-mans land, and right up to the trenches without being seen. They easily routed the British Fifth Army, and part of the Third Army, to its left. Within a day, they opened a gap 50 miles wide and penetrated seven miles deep. Within a week, they were almost half way to Paris. The allied generals were paralyzed. On March 25, Field Marshal Haig of the B.E.F. communicated an order to the French that he was slowly withdrawing to the Channel Ports, and he requested 20 French divisions to cover his right flank, to prevent German encirclement. [48] General Pétain, a day earlier, ordered his Army to fall back and cover Paris. The lack of an allied leader, and the lack of reserves to plug the gap caused the generals to look out for their separate interests. As a result, the hole in the front widened, and the Germans were about to pour in. [49] [50]

In London, the British War Cabinet was unaware of the seriousness of the problem. On the third day of the battle, an officer from the front, Colonel Walter Kirke, was flown in to brief them. Major General Frederick Maurice, who was present, said, the "War Cabinet (was) in a panic and talking of arrangement for falling back on the Channel ports and evacuating our troops to England." [51] Meanwhile, an all out effort was made to get as much manpower to the front as fast as possible. Lord Milner wrote,

On March 23rd, my birthday, I received a call from the Prime Minister who wanted me to go over to France and report personally on the position of affairs there. I left the next day. On March 26th, at 8 in the morning, I drove to a meeting at Doullens, France, arriving there at 12:05pm. Immediately I met Generals Haig, Petain, Foch, Pershing, their staff officers, and President [lower-alpha 2] Clemenceau. The front had broken wide open in front of us, threatening Paris. There was confusion in the ranks as to what to do, and who was in charge. I immediately took the generals aside, and using the powers entrusted with me as the Prime Minister's representative, I deputised General Foch, making him the Allied Commander at the front, and told him to make a stand.

That stand was taken at Amiens, a town with a critical railway station, that, if taken, could have divided the Allies in half, driving the British into the sea, and leaving Paris and the rest of France open for defeat. When Milner returned to London, the War Cabinet gave him its official thanks. [52] On 19 April he was appointed Secretary of State for War in place of the Earl of Derby, who had been a staunch ally of Field-Marshal Haig, and presided over the Army Council for the remainder of the war.

Captain Leo Amery, who was stationed in Paris at the time, was ordered to pick Milner up at the Port of Boulogne and to drive him to Paris. He did this, and the next morning, March 25, he drove Lord Milner to meet Prime Minister Clemenceau. Amery waited outside of Clemenceau's office. When Milner reappeared 30 minutes later, he told Amery what had happened. Clemenceau had pressed for a single command, but preferred General Pétain. Milner preferred Foch, he was firm about it, and Clemenceau agreed. He then said to Amery, "I hope I was right. You and Henry have always told me Foch is the only big soldier." [53] Henry was General Henry Wilson, Lord Milner's recently installed Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), who, like Milner, was in France to assess the military situation. Although Prime Minister Clemenceau tried to set up a meeting that afternoon to finalise things, the British generals were too far away, and the meeting was postponed until the next morning, at the town hall of Doullens, France.

British War Cabinet member George Barnes noted this about Lord Milner:

No better selection could have been made as British representative when the time came to bring about unity of command in France. He never got the recognition due to the part he played in the proceedings at Doullens when General Foch was appointed Generalissimo of the Allied Forces. It has been said that every one was by that time in favour of the step being taken, but even if that were so-and it had by no means been made clear to Downing Street-to Lord Milner belongs the credit of having given it the final push. At the Doullens Conference it was he who took out Haig and then Clemenceau and got their assent, one by one, so preparing the ground for final and unanimous adoption of the proposal.

Historian Edward Crankshaw sums up:

Perhaps the most striking of all his exercises ... and certainly one of the most fruitful of good, was when as a member of the War Cabinet in 1918 he signed Foch into the supreme command, as it were between lunch and tea.

The appointment of Ferdinand Foch had immediate consequences. Before the Doullens meeting broke up, he ordered the Allied generals to make a stand, and to reconnect the front. Whatever panic that may have been underway ended. Both General Petain's and Field Marshal Haig's orders were nullified by Foch's appointment. The front slowly came back together. By late July 1918, the situation had so improved that General Foch ordered an offensive. The Germans were slowly pushed back at first, until momentum gave way to the allies. This part of the war became known as the 100 Days Offensive. It ended with the Germans requesting an armistice. This occurred at 11:00 am, on the morning of November 11, 1918. Finally, the war was over. Lord Milner's decision is best summed up by an inscription at the front of Doullens Town Hall that reads ..."This decision saved France and the freedom of the world."

Postwar

Following the khaki election of December 1918, Lord Milner was appointed Secretary of State for the Colonies and, in that capacity, attended the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, where, on behalf of the United Kingdom, he became one of the signatories of the Treaty of Versailles, including the "Orts-Milner Agreement" allowing to Belgium the administration of Ruanda-Urundi territories to reward the Belgo-African army ("Force publique") for its war effort which highly contributed to pushing German troops out of the future Tanganyika Territory, as in the victorious Tabora and Mahenge battles. [54]

The peace treaty

Due to his responsibilities at the Colonial Office, Milner travelled back and forth to France as a Paris Peace Plan Delegate. From February 1919 until the treaty signing, he made five trips to Versailles, each lasting on average one to two weeks. On May 10, 1919, he flew to Paris for the first time. The trip took two and a half hours, halving the time it took by train, boat, and car. As part of the British Empire Delegation (over 500 members of Britain's colonies and Dominions travelled to Paris), the Prime Minister asked Lord Milner and Arthur Balfour to stand in for him whenever he returned to England for political business. As Secretary of State for the Colonies, Milner was appointed to head up the Mandates Commission by the Big Four, which would decide the fate of the German colonial empire. [55] [56]

Milner was present at an important meeting at 23 Rue Nitot, Lloyd George's flat in Paris, on June 1, 1919, when the Empire Delegation discussed Germany's counterproposals to the peace treaty.

The Peace Treaty of Vereeniging (pronounced "ver-eni-gang"), signed May 31, 1902, ended the Second Boer War between England and the native Dutch settlers of South Africa. Expensive and costly, the conflict concluded with the complete surrender of the Boer foe. Recognizing this, Lord Milner, the High Commissioner of South Africa, wanted tough terms. However, his military advisor, General Kitchener, thought otherwise. Benevolence prevailed, and a firm and lasting peace was made. Even when a new administration in Britain returned the government back to the Boers, the Afrikaners remained firm allies with Great Britain in World War I. To quote Lloyd George, "In Paris, Milner joined with his former antagonists in resistance to that spirit of relentlessness which would humiliate the vanquished foe and keep them down in the dust into which they had been cast..." [57]

Present at the Rue Nitot meeting were Louis Botha and Jan Smuts, former Boer leaders during that war, but now Dominion leaders. On the anniversary of the signing of the South African peace treaty, Prime Minister Botha of South Africa put his hand on Lord Milner's shoulder and said: "Seventeen years ago my friend and I made peace in Vereeniging...It was a hard peace for us to accept, but as I know it now, when time has shown us the truth, it was not unjust - it was a generous peace that the British people made with us, and this is why we stand with them today side by side in the cause which has brought us all together." [58]

In a last minute attempt to improve the conditions imposed on Germany, Lloyd George went back to Prime Minister Clemenceau and President Woodrow Wilson to ask for revisions. He told them that without substantial changes to bring the treaty closer in line with the Fourteen Points, Britain would not take part in an occupation of Germany, nor would its navy resume its blockade of Germany if it failed to sign the treaty. However, President Wilson was tired from all the hard work he had put into the original draft (all decisions and work were made at the top by the Big Four), and Prime Minister Clemenceau refused to budge on the war guilt clause and huge financial reparations, which in 2020 dollars amounted to close to $250 billion (and were not part of the 14 Points). In the end, minor territorial concessions were made, the most important being a reduction in the occupation of the Rhineland by the allies from 20 to 15 years.[ citation needed ]

The treaty signing

On June 16, the Allies gave an ultimatum to Germany and fixed the date of the treaty signing for the 28th. This caused a collapse of the conservative government in Germany on the 21st, and a rise of a liberal one. Two delegates were then rushed to Versailles, arriving on the 27th. When the peace treaty ceremonies commenced at 3 pm on the 28th, and the German delegates entered the Hall of Mirrors, Lloyd George was unsure if they would sign or not, so he had them sign the document first, at 3:12 pm. [59] The entire ceremony took an hour, with a total of 68 plenipotentiarians signing the treaty. Lord Milner, for his part, spent the morning in session with his mandates committee (colonial possessions were resolved after the treaty signing), and motored to the Hall of Mirrors after lunch. He arrived slightly after 2 pm, and he signed the treaty early. The British were the third group of delegates to sign, after the Germans and Americans, and Lord Milner was the 8th signatory to the Treaty of Versailles. He recalls the experience thus, "Though the occasion was such a solemn one and there was a great crowd, I thought it all singularly unimpressive." [60] Marshal Foch commented, "This is not Peace. It is an Armistice for Twenty Years." [61]

On thoughts of a sustainable peace, author John Evelyn Wrench wrote:

If humanity is to be saved from the nightmare of another Armageddon it will only be by the creation of a new world-order. These million-odd words of the Peace Treaty, with all its seals and signatures, will mean nothing if there is not a change in heart, not only in Germany, but in all nations. The League of Nations by which we set so much store will be reduced to impotence if it is not backed by the moral forces of an enlightened public opinion...

In May 1919, shortly after the Germans replied to the peace treaty proposals, American Peace Plan Delegate Dr. James T. Shotwell noted in his diary:

May 31, 1919:

"The day was spent mostly on the German negotiations; a hard day's work drafting the reply. I got the reparations committee to take up again the question of opening the Austrian archives, and spent some of the rest of the day on the text of the reply to the Germans, which is to be discussed with (George) Barnes at dinner this evening."June 1, 1919:

"Things have got into a very bad condition here. This is no secret ... a part of the British Cabinet is up in arms." "A remark was made to me last night that just as it was Lord Milner who came in at the critical point in the War and forced through the Single Command, it may be Milner who will save the situation again. In any case, whatever comes of it, this meeting of the British Cabinet is of great historical importance. Just how the Conference will develop now is hard to say. We may conceivably have an entirely new peace conference."

With Lord Milner's strong personal rapport with Georges Clemenceau, [62] [63] perhaps the two of them could have persuaded President Wilson to bring the peace treaty closer in line with the President's own 14 Points. Certainly, there were those in England who thought that the Prime Minister should have stayed at home and delegated the detailed task of peacemaking to subordinates. Of the Allies, the French were the main obstacle to a fairer peace, so the likes of Lord Milner in charge could have been the catalyst for a permanent peace, one that would have avoided the start, just three months later, of Adolf Hitler's rise to power. [64]

Last years

Right until the end of his life, Lord Milner would call himself a "British race patriot" with grand dreams of a global Imperial parliament, headquartered in London, seating delegates of British descent from Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. He retired in February 1921 and was appointed a Knight Companion of the Garter (KG) on 16 February 1921. [65] On 26 February 1921 he married Lady Violet Cecil, widow of Lord Edward Cecil, and remained active in the work of the Rhodes Trust, while accepting, at the behest of Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, the chairmanship of a committee to examine a new Imperial Preference tariff. His work, however, proved unsuccessful when, following an election, Ramsay MacDonald assumed the office of Prime Minister in January 1924.

Death

Seven weeks past his 71st birthday, Milner died at Great Wigsell, East Sussex, of sleeping sickness, soon after returning from South Africa. His viscountcy, lacking heirs, died with him. His body was buried in the graveyard of the Church of St Mary the Virgin, in Salehurst in the county of East Sussex. There is a memorial tablet to him at Westminster Abbey which was unveiled on 26 March 1930. [66]

He was instrumental in making Empire Day a national holiday on 24 May 1916. [67] In October 1919, it was Lord Milner's suggestion, from Leo Amery, that a two-minute moment of silence be heard on every anniversary of the armistice. [68] [69]

Depictions

Lord Milner is seated third from the right in William Orpen's famous Hall of Mirrors painting.

The town of Milnerton, South Africa is named in his honour.

He was lionised, along with other members of the British War Cabinet, in an oil painting, Statesmen of World War I, on display today at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Credo

Found among Milner's papers was his Credo , which was published in The Times, republished as a pamphlet, and distributed to schools and other public institutions to great acclaim: [70]

"I am a Nationalist and not a cosmopolitan .... I am a British (indeed primarily an English) Nationalist. If I am also an Imperialist, it is because the destiny of the English race, owing to its insular position and long supremacy at sea, has been to strike roots in different parts of the world. I am an Imperialist and not a Little Englander because I am a British Race Patriot ... The British State must follow the race, must comprehend it, wherever it settles in appreciable numbers as an independent community. If the swarms constantly being thrown off by the parent hive are lost to the State, the State is irreparably weakened. We cannot afford to part with so much of our best blood. We have already parted with much of it, to form the millions of another separate but fortunately friendly State. We cannot suffer a repetition of the process."

On the South African War:

"The Dutch can never form a perfect allegiance merely to Great Britain. The British can never, without moral injury, accept allegiance to any body politic which excludes their motherland. But British and Dutch alike could, without moral injury, without any sacrifice to their several traditions, unite in loyal devotion to an empire-state, in which Great Britain and South Africa would be partners, and could work cordially together for the good of South Africa as a member of that great whole. And so you see the true Imperialist is also the best South African." From the Introduction to, 'The Times' History of the war in South Africa, Vol VI (1909). [71]

Evaluation

According to the Biographical Dictionary of World War I: "Milner, on March 24, 1918 crossed the Channel and two days later at Doullens convinced Premier Georges Clemenceau, an old friend, that Marshal Ferdinand Foch be appointed commander in chief of the Allied armies in France." [72] Today, at the entrance to Doullens Town Hall stand two plaques, one written in French, the other in English, that say, "This decision saved France and the freedom of the world."

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica , 1922 edition: "it was largely owing to his influence that Gen. Foch was appointed Generalissimo of the Allied forces in France. It being vital to have a man of unusual capacity and vigour at the War Office in this critical spring of 1918, he was given the seals of Secretary of State for War on April 19; and it was he who presided over the Army Council during the succeeding months of the year which ended with victory." [73]

According to Colin Newbury: "An influential public servant for three decades, Milner was a visionary exponent of imperial unity at a time when imperialism was beginning to be called into question. His reputation exceeded his achievements: Office and honours were heaped upon him despite his lack of identification with either major political party." [74]

According to historian Caroline Elkins, Milner "firmly believed in racial hierarchy." [75] Milner advanced ideas of British superiority and state-directed social engineering. [75]

Honours

- CB: Companion of the Order of the Bath – 1894

- KCB: Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath – 1895

- GCMG: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George – 1897

- GCB: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath – 1 January 1901 – New Year's honours list [8]

- KG: Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter – 1921

Works

- Alfred Milner, England in Egypt (1894) online free

- Alfred Milner, Arnold Toynbee: A Reminiscence (1895) online free

- Alfred Milner, Never Again: A speech given in Cape Town on April 12, 1900

- Alfred Milner, Speeches of Viscount Milner (1905) online free

- Alfred Milner, Transvaal Constitution. Speech at the House of Lords 31 July 1906

- Alfred Milner, Sweated Industries Speech (1907) online free

- Alfred Milner, Constructive Imperialism (1908) online free

- Alfred Milner, Speeches Delivered in Canada in the Autumn of 1908 (1909) online free

- Government, A Unionist Agricultural Policy (1913) online free

- Alfred Milner, The Nation and the Empire; Being a collection of speeches and addresses (1913) online free

- Alfred Milner, Life of Joseph Chamberlain (1914) online free

- Alfred Milner, Cotton Contraband (1915) online free

- Alfred Milner, Fighting For Our Lives (1918) trove subscription

- Alfred Milner, The British Commonwealth (1919) (summary of, pgs. 197–198, 352: Link)

- Government, Great Britain's Special Mission to Eqypt (1920)

- Government, Report of the Wireless Telegraphy Commission (1922) online free

- Alfred Milner, Questions of the Hour (1923) online free ('Credo' in 1925 edition)

- Alfred Milner, The Milner Papers: South Africa 1897-1899 ed by Cecil Headlam (London 1931, vol 1)

- Alfred Milner, The Milner Papers: South Africa 1899-1905 ed by Cecil Headlam (London 1933, vol 2) free online

- Alfred Milner, Life in a Bustle: Advice to Youth (2016), London: Pushkin Press, OCLC 949989454

See also

- Oxford University - Lord Milner was elected Chancellor of Oxford University

- London School of Economics - Lord Milner was elected an Honorary Governor of the London School of Economics [76]

- Pro-Jerusalem Society - Viscount Milner was Honorary Member of its leading Council

Related Research Articles

The Orange River Colony was the British colony created after Britain first occupied (1900) and then annexed (1902) the independent Orange Free State in the Second Boer War. The colony ceased to exist in 1910, when it was absorbed into the Union of South Africa as the Orange Free State Province.

William Waldegrave Palmer, 2nd Earl of Selborne, styled Viscount Wolmer between 1882 and 1895, was a British politician and colonial administrator, who served as High Commissioner for Southern Africa.

Louis Botha was a South African politician who was the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa – the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war veteran during the Second Boer War, he eventually fought to have South Africa become a British Dominion.

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senior military officers and opposition politicians as members.

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

Violet Georgina Milner, Viscountess Milner was an English socialite of the Victorian and Edwardian eras and, later, editor of the political monthly National Review. Her father was close friends with Georges Clemenceau, she married the son of Prime Minister Salisbury, Lord Edward Cecil, and after his death, Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner.

Milner's Kindergarten is the informal name of a group of Britons who served in the South African civil service under High Commissioner Alfred, Lord Milner, between the Second Boer War and the founding of the Union of South Africa in 1910. It is possible that the kindergarten was Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain's idea, for in his diary dated 14 August 1901, Chamberlain's assistant secretary Geoffrey Robinson wrote, "Another long day occupied chiefly in getting together a list of South African candidates for Lord Milner – from people already in the (Civil) Service". They were in favour of the unification of South Africa and, ultimately, an Imperial Federation with the British Empire itself. On Milner's retirement, most continued in the service under Lord Selborne, who was Milner's successor, and the number two-man at the Colonial Office. The Kindergarten started off with 12 men, most of whom were Oxford graduates and English civil servants, who made the trip to South Africa in 1901 to help Lord Milner rebuild the war torn economy. Quite young and inexperienced, one of them brought with him a biography written by F.S. Oliver on Alexander Hamilton. He read the book, and the plan for rebuilding the new government of South Africa was based along the lines of the book, Hamilton's federalist philosophy, and his knowledge of treasury operations. The name, "Milner's Kindergarten", although first used derisively by Sir William Thackeray Marriott, was adopted by the group as its name.

A ginger group is a formal or informal group within an organisation seeking to influence its direction and activity. The term comes from the phrase ginger up, meaning to enliven or stimulate. Ginger groups work to alter the organisation's policies, practices, or office-holders, while still supporting its general goals. Ginger groups sometimes form within the political parties of Commonwealth countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, and Pakistan.

The Supreme War Council was a central command based in Versailles that coordinated the military strategy of the principal Allies of World War I: Britain, France, Italy, the United States, and Japan. It was founded in 1917 after the Russian Revolution and with Russia's withdrawal as an ally imminent. The council served as a second source of advice for civilian leadership, a forum for preliminary discussions of potential armistice terms, later for peace treaty settlement conditions, and it was succeeded by the Conference of Ambassadors in 1920.

The Bloemfontein Conference was a meeting that took place at the railway station of Bloemfontein, capital of the Orange Free State from 31 May until 5 June 1899. The main issue dealt with the status of British migrant workers called "Uitlanders", who mined the gold fields in Transvaal.

The Doullens Conference was held in Doullens, France, on 26 March 1918 between French and British military leaders and governmental representatives during World War I. Its purpose was to better co-ordinate their armies' operations on the Western Front in the face of a dramatic advance by the German Army which threatened a breakthrough of their lines during the war's final year. It occurred due to Lord Alfred Milner, a member of the British War Cabinet, being dispatched to France by Prime Minister Lloyd George, on 24 March, to assess conditions on the Western Front, and to report back.

The Dury, Compiègne and Abbeville meetings were held by the Allies during World War I to address Operation Michael, a massive German assault on the Western Front on 21 March 1918 which marked the beginning of the Kaiser's Spring Offensive. Since the fall of 1917, a stalemate had existed on the Western Front. However, German victory against Russia in 1917, due to the Russian Revolution and the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, freed up German armies on the Eastern Front for use in the west. During the winter of 1917-1918, approximately 50 German divisions in Russia were secretly transported by train to France for use in a massive, final attack to end the war. The battle that followed, Operation Michael, totally surprised the Allies and nearly routed the French and English armies from the field. The meetings below were held under these dire circumstances.

The War Policy Committee was a small group of British ministers, most of them members of the War Cabinet, set up during World War I to decide war strategy. The committee was created at the request of Lord Milner on 7 June 1917, through a memorandum he circulated with his peers on the British War Cabinet. Its members included the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, Lord Milner, Edward Carson, Lord Curzon and Jan Smuts. The committee was formed to discuss the strategic matter of the Russian Revolution, and the new entry of The United States. Coincidentally or not, the timing of Lord Milner's memo coincided with the detonation of 19 underground mines filled with explosives on the Western Front, which created the largest human explosion of all time. The night before this explosion, General Harington said to reporters "Gentleman, I don't know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change the geography". In Milner's memo, he stressed that the allies must act together for the common good, and not devolve to piecemeal arrangements that satisfied specific countries. The War Policy Committee was formed, and it discussed every major initiative taken by the allies until the end of the war. It was chaired by Lord's Milner and Curzon, with Jan Smuts as its Vice Chairman.

The X Committee was established during World War I by Lord Alfred Milner as a way of managing and providing strategic direction to the Great War. Its members included Prime Minister Lloyd George, Lord Milner, General Henry Wilson, and Maurice Hankey as its Secretary. Hankey delegated his responsibility to Leo Amery. Meetings were held at 10 Downing Street, sometimes once, sometimes twice daily. Amery says the X Committee "really ran the war during the critical spring and summer months" of 1918. The X Committee's first meeting was held on 15 May 1918, and its last meeting on 25 November 1918. From a biography written about his father, the son of Jan Smuts revealed that the words "X Committee" stood for "Executive Committee", and that Lord Milner must have learned about it during his time in South Africa (1897–1905).

The Monday Night Cabal was a 'ginger group' of influential people set up in London by Leo Amery at the start of 1916 to discuss war policy. The nucleus of the group consisted of Lord Milner, George Carson, Geoffrey Dawson, Waldorf Astor and F. S. Oliver. The group got together for Monday night dinners and to discuss politics. Throughout 1916 their numbers and influence grew to include Minister of Munitions David Lloyd George, General Henry Wilson, Philip Kerr, and Mark Jameson. It is thought that word of the Ginger Group reached Douglas Haig, prompting him to invite Lord Milner to France in November for an 8-day tour of the Western Front. It was through the Ginger Group that Times editor Geoffrey Dawson published a December 4, 1916 news story titled "Reconstruction" that set in motion events that caused Prime Minister H. H. Asquith to resign, signaling the rise of the Lloyd George Ministry. Among the group's primary objectives was the formation of a small war cabinet within government to fight the war against the German Empire effectively. This point was advanced by The Times as early as April 1915, so it is unknown if the Ginger Group, or one its predecessor elements was responsible for the idea behind Lloyd George's decision to create a War Cabinet on the day he was appointed Prime Minister. However, his surprise choice of Lord Milner as one of the War Cabinet's five members shows the influence of the ginger group on him.

The onset of the 20th century saw England as the world's foremost naval and colonial power, supported by a 100,000-man army designed to fight small wars in its outlying colonies. Since the Napoleonic Wars nearly a century earlier, Britain and Europe had enjoyed relative peace and tranquility. The onset of World War I caught the British Empire by surprise. As it increased the size of its army through conscription, one of its first tasks was to impose a complete naval blockade against Germany. It was not popular in the United States. However, it was very important to England.

The Garden Suburb is the name given to a collection of ministerial positions created by the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George in December 1916, to help facilitate the running of World War I. They were housed in temporary wooden structures in the Garden of 10 and 11 Downing Street. Due to their contacts with the press, they were sometimes regarded with suspicion, and their ideas at times created trouble for the Cabinet Secretary Maurice Hankey, who was charged not just with supervising the taking of minutes at War Cabinet meetings, but also with executing their decisions. Known as the Prime Minister's personal secretariat and private "brain trust", the Garden Suburb included the likes of Professor W. G. S. Adams, Lord Milner, Philip Kerr and Waldorf Astor.

The Beauvais Conference of World War I was held at the request of French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau to solidify command of the Western Front and to ensure the maximum participation of France's allies in the war. The conference was held on April 3, 1918, at Beauvais Town Hall, France, one week after the Doullens Conference that appointed General Ferdinand Foch as Commander of the Western Front. Clemenceau thought the wording of the Doullens Agreement was too weak, and that a correction was needed to solidify Foch's command. The urgency of the meeting was underpinned by Germany's Spring Offensive on the Western Front, which opened a gap 50 miles wide and 50 miles deep in the line, forcing the British Expeditionary Force to reel back, and retreat orders from both French and British army commanders to protect their armies.

J. Frederick "Peter" Perry (1873-1935) was a British colonial employee best known for his work as a member of Milner's Kindergarten in South Africa, immediately after the end of the Second Boer War.

The Rue Nitot meeting was an important First World War event, when the British Empire delegates at the Peace Conference in Versailles got together to register the harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles, and tried to soften the conditions for peace with Germany. The meeting was held at Prime Minister David Lloyd George's flat, 23 Rue Nitot, in Paris, on June 1, 1919.

References

Notes

- ↑ Bill passed by Parliament 4 May 1916

- ↑ "President" in this context means "President of the Council of Ministers", the official title of the Prime Minister of France, not the President of the Republic. The latter office was held by Raymond Poincare who was also present at Doullens.

Citations

- ↑ New College Bulletin, November 2008

- 1 2 3 Chisholm 1911, p. 476.

- ↑ Milner 1894.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, pp. 476–477.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Chisholm 1911, p. 477.

- 1 2 3 Hochschild 2011, pp. 28–32.

- ↑ Smuts 1966, p. 95.

- 1 2 "No. 27264". The London Gazette . 8 January 1901. p. 157.

- ↑ "No. 27338". The London Gazette . 26 July 1901. p. 4919.

- ↑ "No. 27318". The London Gazette . 28 May 1901. p. 3634.

- ↑ "Lord Milner in the City". The Times. No. 36515. London. 24 July 1901. p. 12.

- ↑ Surridge 1998, pp. 112–154.

- ↑ "No. 27455". The London Gazette . 18 July 1902. p. 4586.

- ↑ "No. 27459". The London Gazette . 29 July 1902. p. 4834.

- ↑ Dubow 1997.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, pp. 477–478.

- ↑ "Letters Patent" . The Times. London. 31 March 1905.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chisholm 1911, p. 478.

- ↑ May, Alexander (1995). The Round Table, 1910-66. University of Oxford (Thesis).

- ↑ Gollin 1964, p. 84.

- ↑ Amery 1953a, p. 174.

- ↑ "Labour Ordinance" . The Times. London. 31 January 1904.

- ↑ Rhodes 1902, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ The Times of London, 20 August 1915, pg. 7

- ↑ The Times of London, 31 August 1915, pg. 9

- ↑ Amery 1953b, p. 93.

- ↑ Thompson 2007, p. 327.

- ↑ Marlowe 1976, p. 250.

- ↑ Marlowe 1976, p. 246.

- ↑ Thompson 2007, p. 329.

- ↑ Wrench 1955, pp. 140–141.

- 1 2 Wrench 1958, p. 317.

- ↑ Parliament Debate, 13 February 1917, pgs. 479-485

- ↑ Hochschild, Adam, "To End All Wars", pgs. 245-246

- ↑ "UK National Archives, CAB 23-1, pg.5 of 593" (PDF). 9 December 1916.

- ↑ Hoschschild, pg. 254

- ↑ CAB 24-3, G-130 & 131, pgs. 300 to 311

- ↑ Jeffery 2006, pp. 182–183, 184–187.

- ↑ Wrench, pgs. 311,312

- ↑ Amery 1969, p. 1001.

- ↑ Hall, H., "The British Commonwealth of Nations", pgs. 274-279

- ↑ Ford 1923, p. 198.

- ↑ Hunt 1982, p. 70.

- ↑ Hochschild 2011, p. 328.

- 1 2 Gollin 1964, p. 448.

- ↑ Woodward 1998, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Stein 1961, pp. 310–311.

- ↑ Lloyd George, David, "War Memoirs of David Lloyd George, Vol. V", pgs. 387-388

- ↑ Lloyd George 1936, p. 389.

- ↑ US Senate Document #354, pg. 7

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin, "Winston S. Churchill, Vol. IV, 1916-1922, 'The Stricken World'", pgs. 77-80 (esp. 80)

- ↑ War Cabinet Minutes, CAB 23-5, pgs. 5 & 6 of 9

- ↑ Amery 1953b, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Louwers 1958, pp. 909–920.

- ↑ Marlowe, pg. 327

- ↑ Gollin, pg. 585

- ↑ Lloyd George, "The Truth About The Peace Treaties, Vol I", pgs. 256-257

- ↑ Wrench 1958, pg. 238

- ↑ Chapman-Huston, "The Lost Historian", pg. 291

- ↑ Wrench 1958, p. 360.

- ↑ Churchill 1948, p. 7.