The History Of The New York Mafia's Five Families, Explained

The mafia is something most of us only know about from movies or some other form of popular culture. Made men, crime bosses, and a lot of criminal activity are basically what you need to know, right?

Wrong.

The history of the American Mafia is long and complicated, extending back centuries and across two continents. And, yes, there are a lot of names. The modern names for the Five Families - Gambino, Genovese, Lucchese, Colombo, Bonanno - were nods to some of the most powerful mafia bosses who ever held power, but those aren't the only individuals who played key roles in developing the sheer might of the New York mafia. So, while some of what The Sopranos and The Godfather show is legitimate, it's only part of the story.

The power of the mafia in the United States was based in New York City. The so-called ‘Five Families’ were in charge of an elaborate criminal underworld built upon alcohol, violence, and loyalty. In fact, the Five Families are linked to the underworld that once (and may still) span across the country.

But, what are the Five Families? Where did they come from? And how did they form?

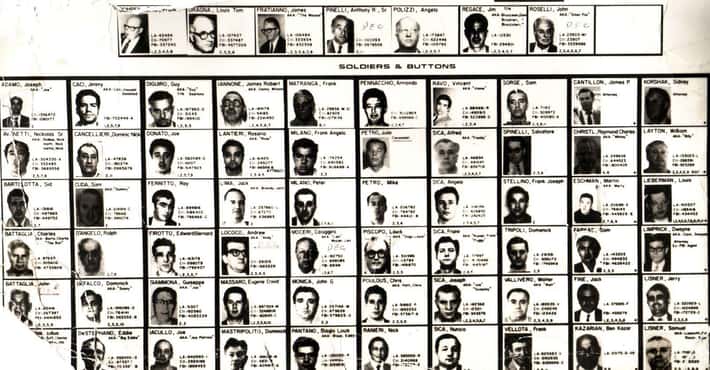

- Photo: FBI / Public domain

The Sicilian Mafia Became Dominant In The US After 'First Mafia War'

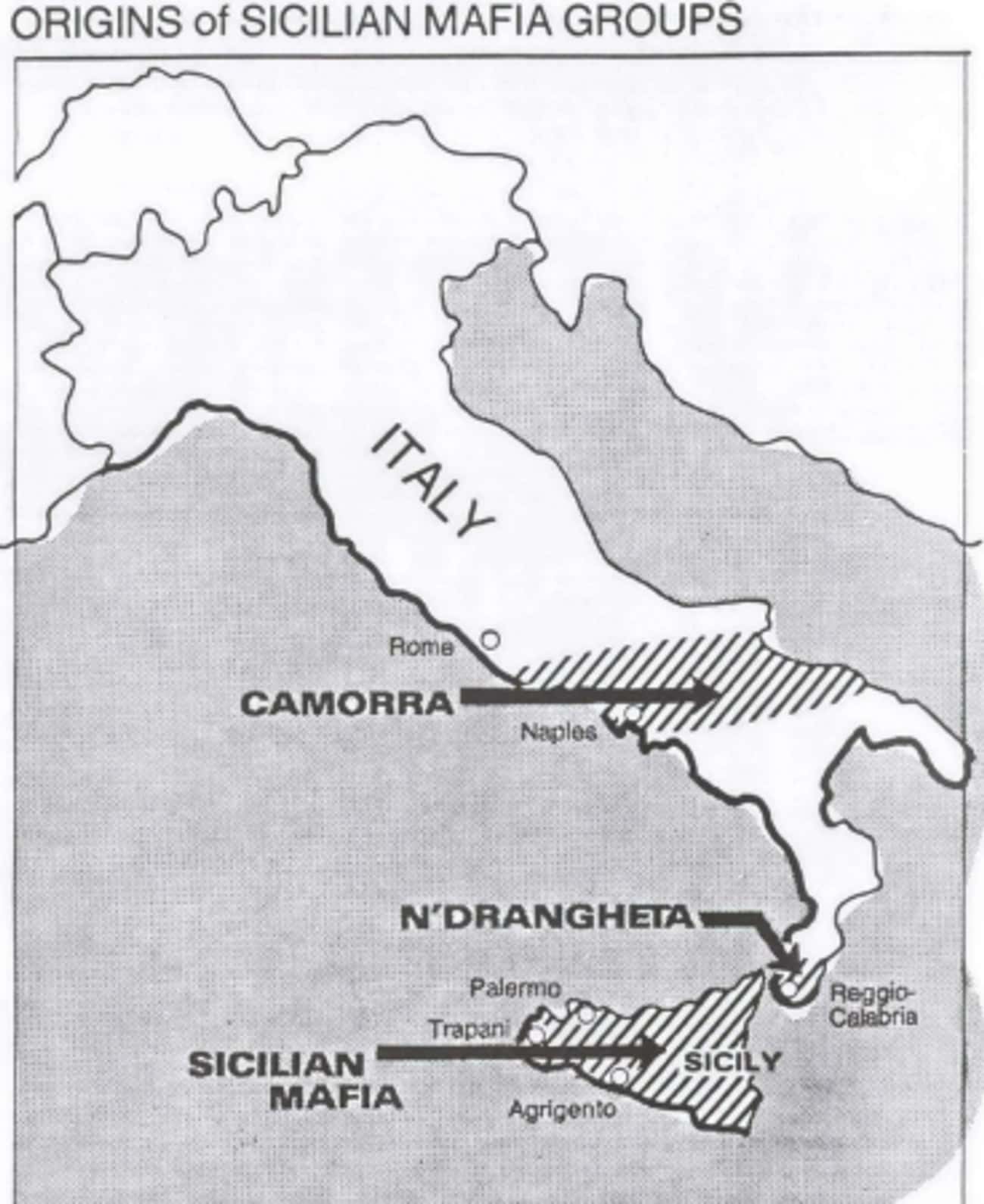

Exactly when bands of men in Sicily started acting as “protectors against the arrogance of the powerful" or mafioso isn't clear but, according to historian Selwyn Raab, there wasn't a criminal connotation to the word mafia until the 19th century. By the mid-1800s, the Sicilian mafia became increasingly defiant of the government and integrated itself into politics and economic activities, using manipulation, coercion, extortion, and other methods to get what it wanted.

In nearby Naples, Italy, the Camorra also emerged by the 1800s. Likely an extension of the prison gang system, the Camorra similarly took part in criminal activities and extended its influence into the United States. As Europeans flocked to cities in the US, New York City grew to become one of the most international cities in the world. By 1920, a substantial portion of the four million Italians who had arrived in the United States since 1880 lived in New York City.

Neapolitans settled in Brooklyn while Sicilians established themselves in Harlem and Manhattan. The two groups came into violent contact with each other, especially as their criminal enterprises like racketeering and gambling crossed paths. The so-called “First Mafia War” played out during the late 1910s.

In late 1916, the leader of the Camorristas, Don Pellegrino Morano, set his sights on eliminating the head of the Sicilian group, Nicholas Morello (also known as Nicholas Terranova) to bring the war to an end. Morano invited Morello and his bodyguard to a meeting in 1916 under the guise of peace. Morello and his bodyguard were ambushed and killed in September 1916. This didn't end the conflict and the back and forth of death continued.

When Ralph Daniello, one of Morano's men, turned on his gang in 1917, it signaled the end for the group from Camorra. Daniello implicated Morano in the murders of Morello and his bodyguard, Charles Ubriaco. Morano was tried, convicted, and sentenced to prison. In the end, the Sicilians emerged as the dominant group, even taking in some former Camorristas after their fall.

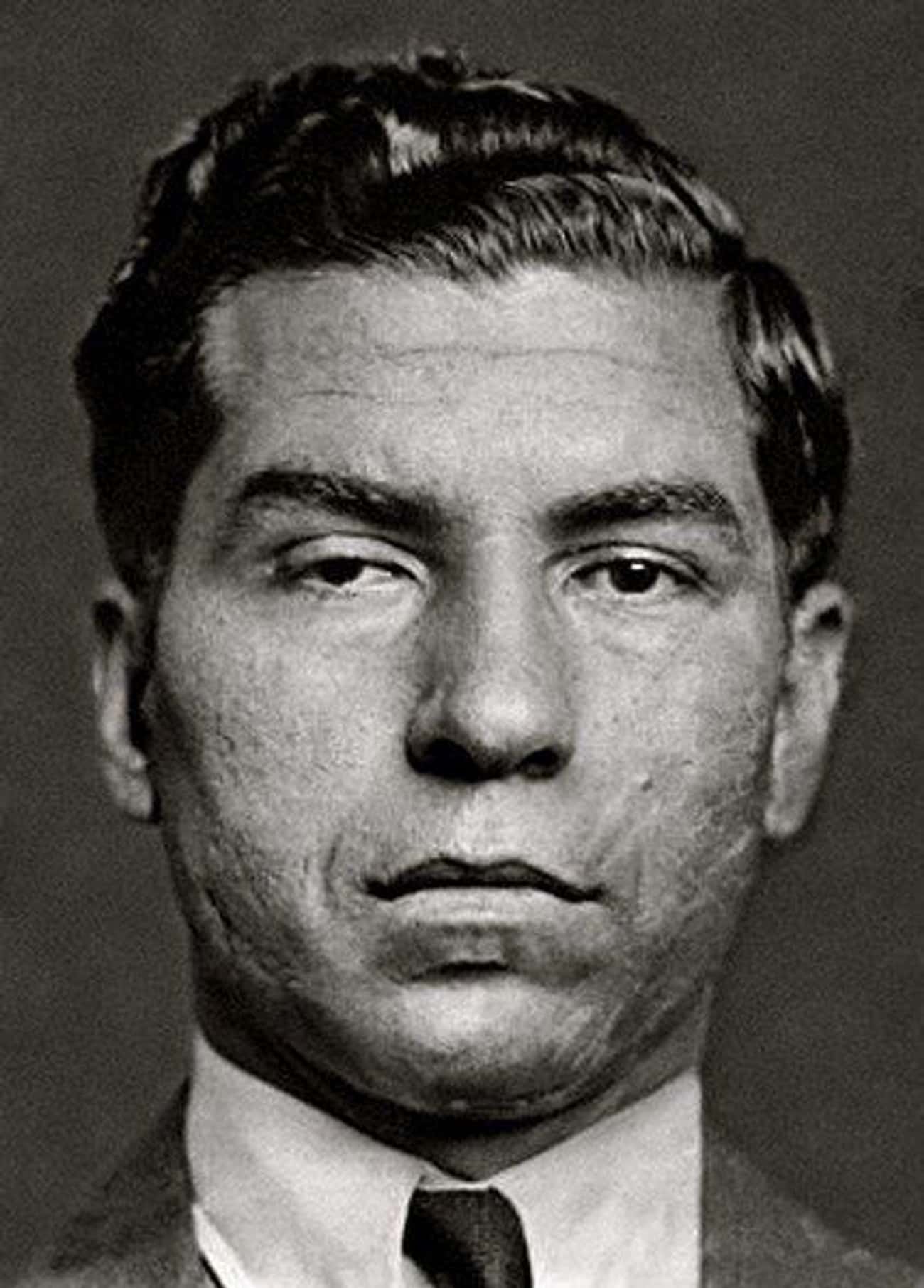

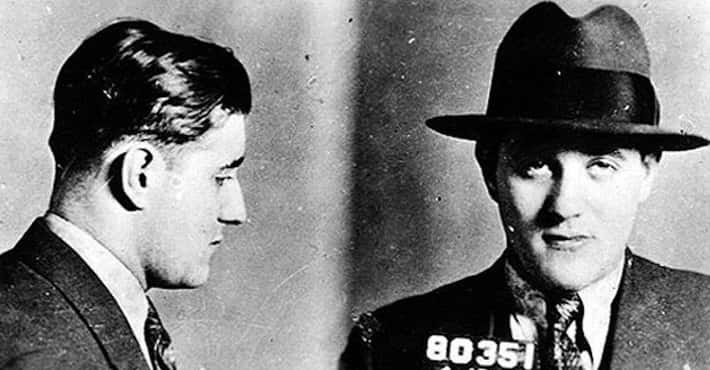

- Photo: New York Police Department / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

Among the large numbers of Sicilian living in the city who became key figures in the mafia during the early 20th century were Giuseppe “Joe” Masseria and Salvatore “Toto” D'Aquila.

Masseria arrived in New York around 1903 after he fled a murder charge in Sicily. He became a member of the first major crime family in the city, the Morello Gang, as did D'Aquila, who established roots in East Harlem after immigrating from Palermo, Sicily, in 1904.

Both D'Aquila and Masseria were in the Morello gang, and when leader Giuseppe Morello and associate Ignazio “The Wolf” Lupo went to prison in during the 1910s (avoiding much of the activity of the "First Mafia War), D'Aquila assumed control of the group. He was, according to sources, considered to be the capo di tutti capi or “boss of all bosses.”

Masseria was less than pleased and worked to undermine D'Aquila. By the time Morello and Lupo were released during the early 1920s, Masseria had usurped much of the bootlegging racket in New York. D'Aquila tried to prevent Masseria's rise to power and sent hitman Umberto Valenti to eliminate him several times. Valenti was ultimately killed, allegedly by Salvatore “Charles Lucky” Luciano, an ally of Masseria. Masseria's survival secured him two monikers, “Joe the Boss” and ”the man who could dodge bullets."

For his part, D'Aquila held his title until 1928 when he was killed. D'Aquila's death signaled the end of the rivalry between the man who laid the foundations for the future Gambino crime family and Joe the Boss. Masseria took over as capo di tutti capi but, unfortunately for him, another threat from Sicily, Salvatore Maranzano, had arrived the previous year.

- Photo: New York Police Department / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

The Sicilian Struggle For Power During The 1920s Led To War

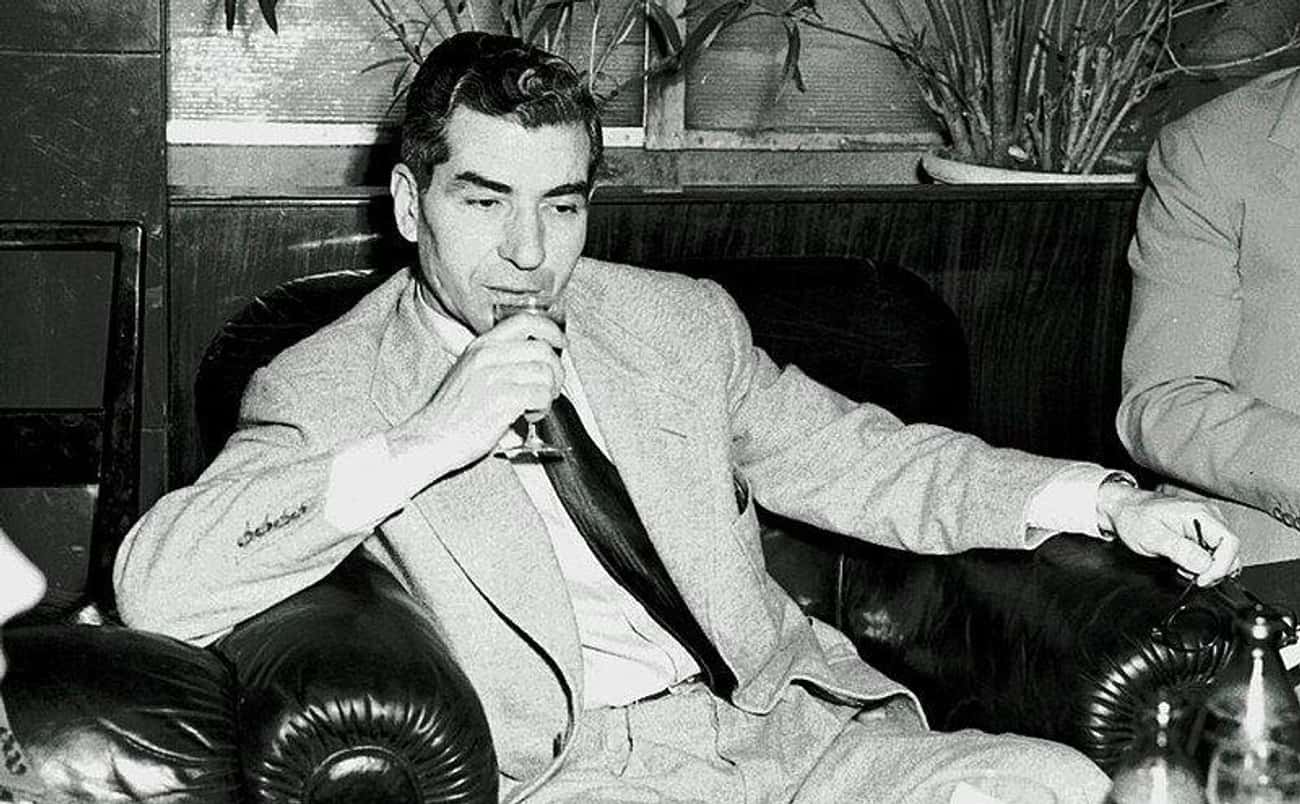

Salvatore Maranzano's arrival in the US in 1927 represented what would be a big shift in organized crime in the country. Sent by Sicilian Don Vito Ferro, Maranzano was tasked with establishing ties with existing gangsters on his behalf.

Maranzano based himself in Brooklyn where he grew a reputable real estate business as well as a bootlegging operation. He made contact with men who had immigrated from his hometown Castellammare del Golfo and was soon aligned with the likes of Giuseppe “Joseph” Bonanno and Giuseppe “Joseph” Profaci. He also attracted the attention of Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria, a fellow Sicilian.

Factions led by Maranzano and Masseria openly sabotaged and undercut each other, and, by 1930, the tension between the two groups was at its breaking point. The Castellammarese War broke out, with Maranzano supported by the aforementioned Bonanno and Profaci as allies. Masseria had Lucky Luciano and Vito Genovese on his side at first. With the struggle leaning in Maranzano's favor by early 1931, Luciano turned on Masseria. In cahoots with Marananzano, Luciano had Masseria killed on April 15, 1931, ending the Castellammarese War.

- Photo: Remo Nassi / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

The New York Mafia Experienced A Watershed Year In 1931

After Masseria's death, Maranzano called together hundreds of gangsters in New York City for a groundbreaking meeting. It was there that Maranzano officially established La Cosa Nostra (Italian for “our thing”) and divided organized crime in New York into five families. Maranzano was the capo di tuti or “boss of the bosses” - the man above the rest. The five families were headed by Joe Profaci, Joseph Bonanno, Tom Gagliano, Vincent Mangano, and Lucky Luciano. Each man had an underboss with a sub-boss, lieutenants, and soldiers rounding out the family structure.

Maranzano told the group that peace and prosperity would rule the day but was aware that Luciano had higher ambitions. By September 1931, Maranzano knew he had to eliminate Luciano and made plans for his assassination. On September 10, 1931, however, Maranzano was killed by assassins sent by Luciano who had found out about the “boss of the bosses” plan.

Luciano engaged men from his friend and Jewish crime boss Meyer Lansky for the job. Killing Maranzano propelled Luciano to the top of organized crime in New York City and also united Italian organized crime activities with non-Italian groups. Luciano created a national crime syndicate called “The Commission” and continued with the five-family structure initiated by Maranzano.

The formalization of the crime families leaned on a solid organizational structure. Bosses or “Dons” headed crime families, while underbosses (sotto capo) were second in command. A boss likely had a consigliere or trusted adviser who generally ranked third in power. Underbosses oversaw capos, men who more or less commanded soldiers and associates. Soldiers were “made men" and had been vouched for by some other member of the family before approval by the Don. Soldiers also took the code of silence (omerta) required for membership. Associates were akin to errand boys who followed orders but didn't hold sway in the family.

- Photo: Walter Albertin / Library of Congress / No known copyright restrictions

The Five Families Built The Foundations Of Their Empires During The 1930s

With the establishment of The Commission, Lucky Luciano - the man who “organized organized crime” - built upon the idea of Salvatore Maranzano and expanded the reach of New York organized crime. The emphasis on loyalty, familial bonds, and maintaining peace remained but The Commission was essentially a way for the five families in New York to reign over families around the US. Described as an “underworld Supreme Court” by author Selwyn Raab, The Commission allocated one vote to each family and seats to men from Chicago and Buffalo.

The five families then focused inwardly. Headed by Joseph “Joe Bananas” Bonanno until the late 1960s, the Bonanno family remained steeped in Sicilian tradition and practices. Bonanno had been a protege of Salvatore Maranzano and the family undertook gambling, loansharking, and drug trafficking operations with members who had bloodlines tied to Sicily.

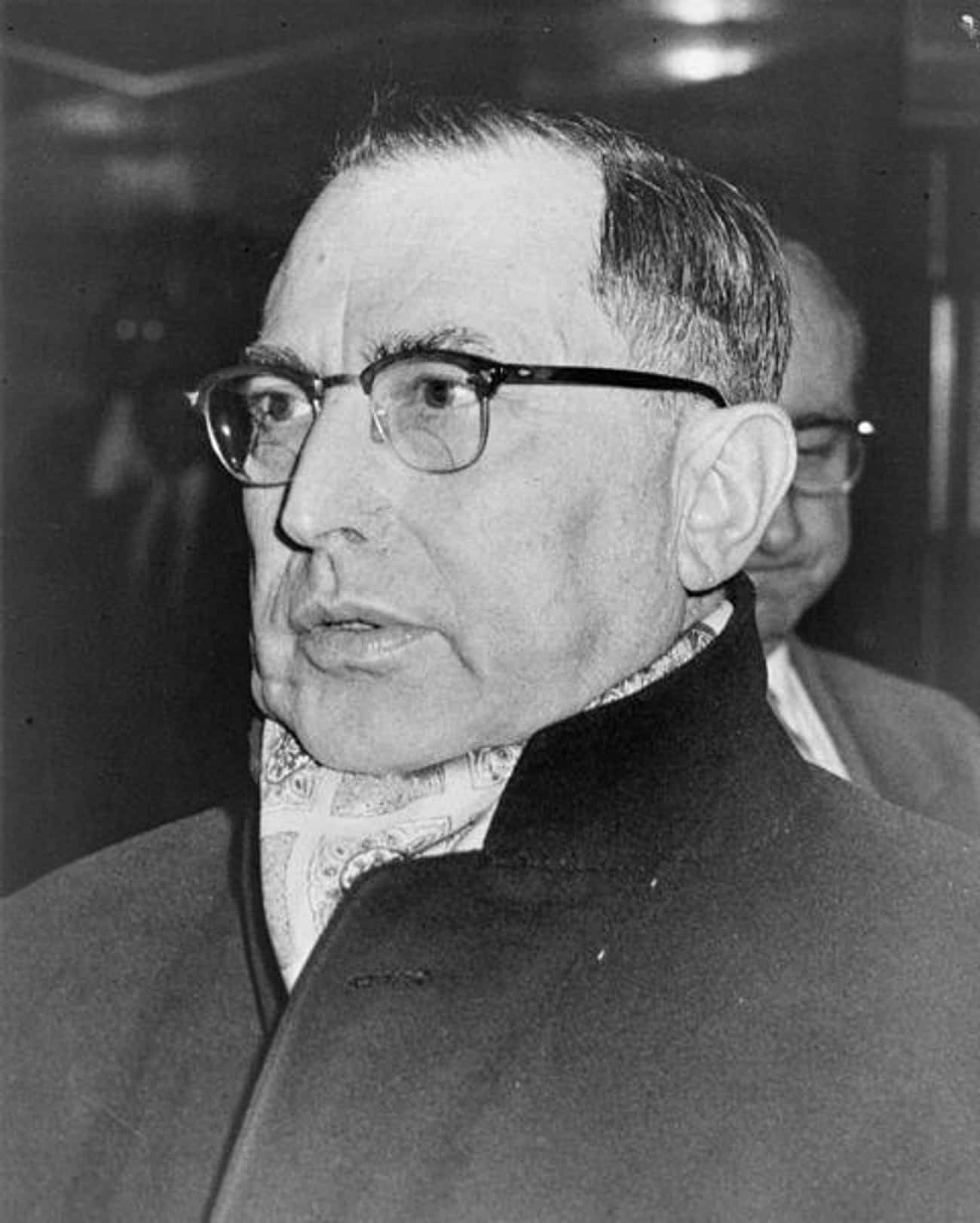

Guiseppe “Joe” Profaci took control of the family named after him (later called the Colombo family,) while Lucky Luciano ran a family of his own group (essentially what was left of Masseria's men.) Luciano went to prison in 1936 and his underboss, Vito Genovese, took over in his absence. When Genovese fled the United States in 1937, Frank “the Prime Minister” Costello took over, but after Luciano was deported in 1947, Costello officially became the boss until 1957.

Vincent Mangano led what would later be called the Gambino family until his disappearance in 1951 and Tommaso “Tommy" Gagliano became boss of the future Lucchese family.

- Photo: Walter Albertin / Library of Congress / No known copyright restrictions

There Were Two Non-New York Families With Voting Rights On The Commission

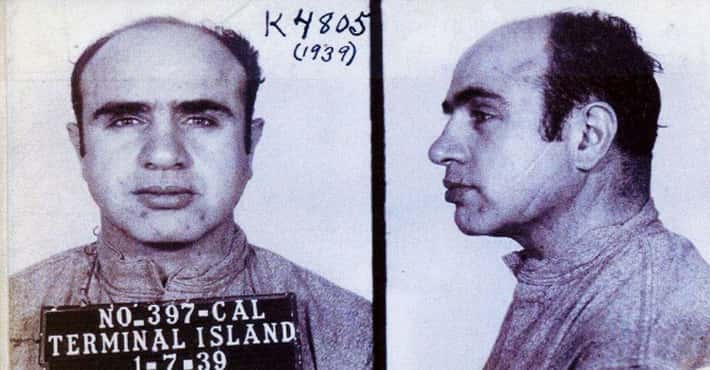

Chicago and Buffalo were the two non-New York City crime families represented on The Commission. The former was led by Alphonse “Al” Capone, while the latter saw Stefano Magaddino at the top.

Capone and his Chicago mafia (called “The Outfit”) were considered more or less on par with New York organized crime. Capone had a relatively short tenure on The Commission because he was convicted of tax evasion in 1931 and sentenced to 11 years in prison. The reason Magaddino and Buffalo were given a seat had to do with the group's control of illegal trade going in and out of Canada.

In addition to The Commission, Luciano formalized links among crime families in the US through a national syndicate. The idea of such a confederation may have been the brainchild of Chicago crime boss Johnny Torrio (Al Capone's mentor) as early as 1929, but it was Luciano who brought it to fruition. The Syndicate, as it became known, wasn't synonymous with the mafia because it wasn't exclusively Sicilian entities. The Syndicate extended from coast-to-coast as a network of Italian, Irish, Jewish, and other criminal organizations under one umbrella.

- Photo: Phil Stanziola / Library of Congress / No known copyright restrictions

The Five Families Went From Calm To Chaos By The Late 1950s

In 1936, Lucky Luciano was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in prison for pandering, leaving his underboss Vito Genovese to take over in his absence. Genovese fled the United States and went to Italy in 1937 to avoid prosecution for the murder of Ferdinand “The Shadow” Boccia in 1934. Luciano, for his part, was paroled after World War II and departed to Italy. He later visited Cuba but was again sent back to Italy.

Boccia was also a member of the Luciano-Genovese crime family, but he and Genovese were at odds over extortion money - a slight Genovese viewed as a betrayal. With both Luciano and Genovese out of commission, so to speak, Frank “The Prime Minister” Costello became the de facto leader.

Even with the shifts in leadership in the Luciano-Genovese family, there was no real drama until 1945 when Genovese returned to the US from Italy. Genovese had been arrested in Italy and sent back to the US, but the key witness against him in the Boccia killing died and charges were dismissed.

The competition for power between Genovese and Costello intensified by the 1950s, especially after the former convinced the Commission to order the assassination of the latter's key gunman, Willie Moretti, in 1951. Moretti's mental faculties were declining due to syphilis, and there was concern about his ability to maintain organizational secrets, a risk highlighted after Moretti had been too forthcoming in his appearance at the Congressional Kefauver Committee one year earlier.

Six years later, Genovese set his sights directly on Costello and tasked Vincente “The Chin” Gigante to eliminate his rival. Gigante failed to kill Costello in 1957, but the incident was enough to send Costello into retirement. This didn't stop Costello's ally Albert “The Mad Hatter” Anastasia from rallying Costello's supporters to push back against Genovese. Anastasia was once the head of the National Crime Syndicate's enforcement arm commonly called Murder, Incorporated.

Anastasia was a member of the Mangano crime family (later called the Gambino crime family) and served as underboss to Vincent Mangano. After Mangano went missing in 1951, Anastasia (believed to have been behind the disappearance) took over Anastasia's efforts on Costello's behalf. They were short-lived, however. On October 25, 1957, he was murdered under the orders of Genovese and Carlo Gambino, Anastasia's underboss. With Anastasia out of the way, Gambino assumed control of the family and Genovese was essentially unopposed to take back the Luciano-Genovese crime family.

- Photo: SakartvelosGaumarjos / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA 4.0

The Apalachin Summit Exposed The Mafia To The Public

When a collection of the most powerful men in the mafia gathered at the home of Joseph “Joe the Barber” Barbara on November 14, 1957, it was purportedly to pay a visit to their ailing associate. In reality, it was a meeting for Cosa Nostra heavyweights to reconcile and establish a functional status quo.

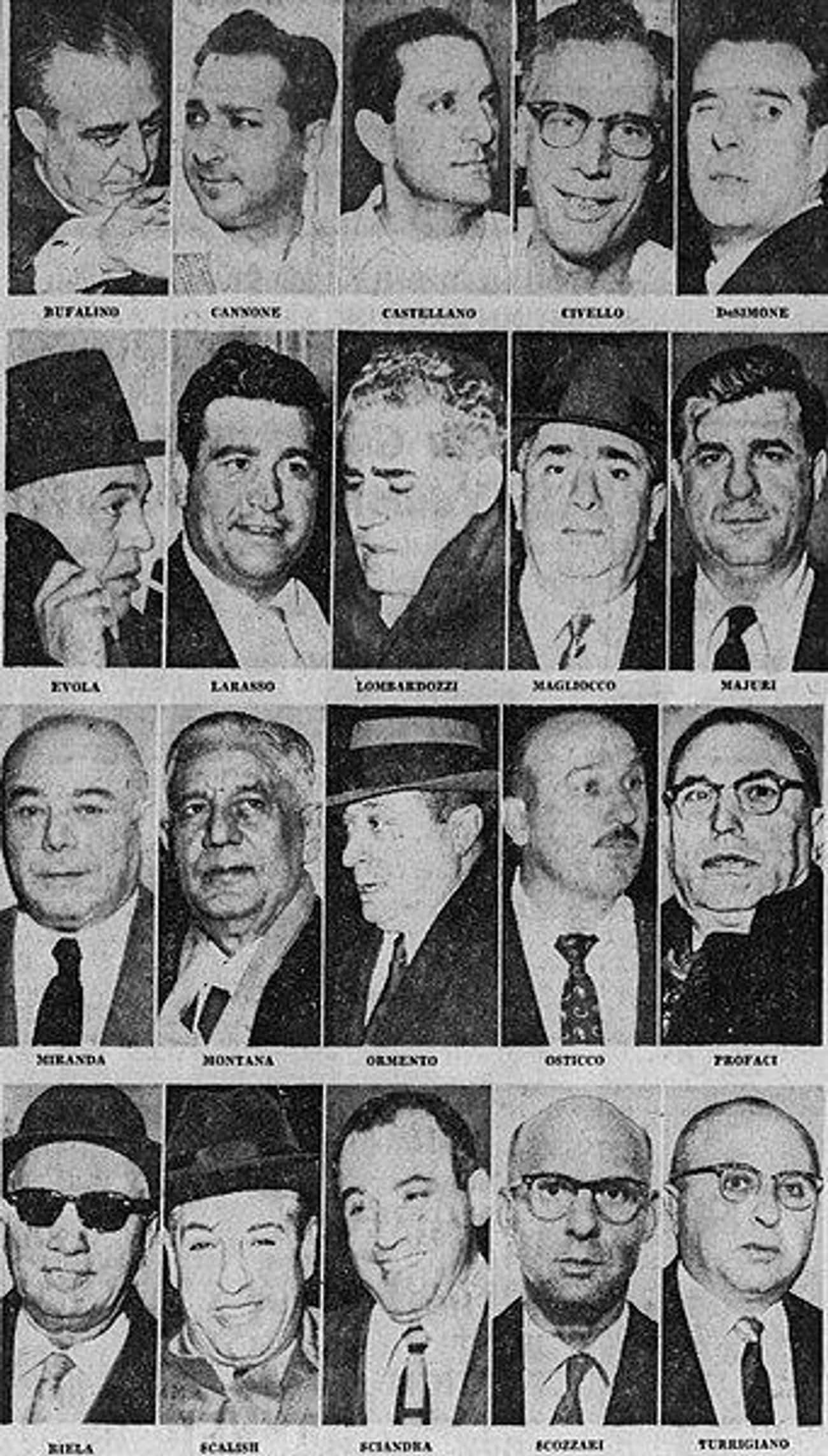

The meeting in Apalachin, New York, included Five Family bosses Joseph Bonanno, Vito Genovese, Carlo Gambino, and Joe Profaci. The Lucchese family, headed by Tommy Lucchese, was represented by Vincent Rao. Other attendees included members of crime families from around the country, their bodyguards, and other trusted guests.

The summit at Apalachin was purportedly Genovese's idea. He wanted to “solidify his position as the undisputed boss in New York” after having eliminated his rivals. Conversations about business interests like narcotics, shipping, manufacturing, and the like were also on the agenda.

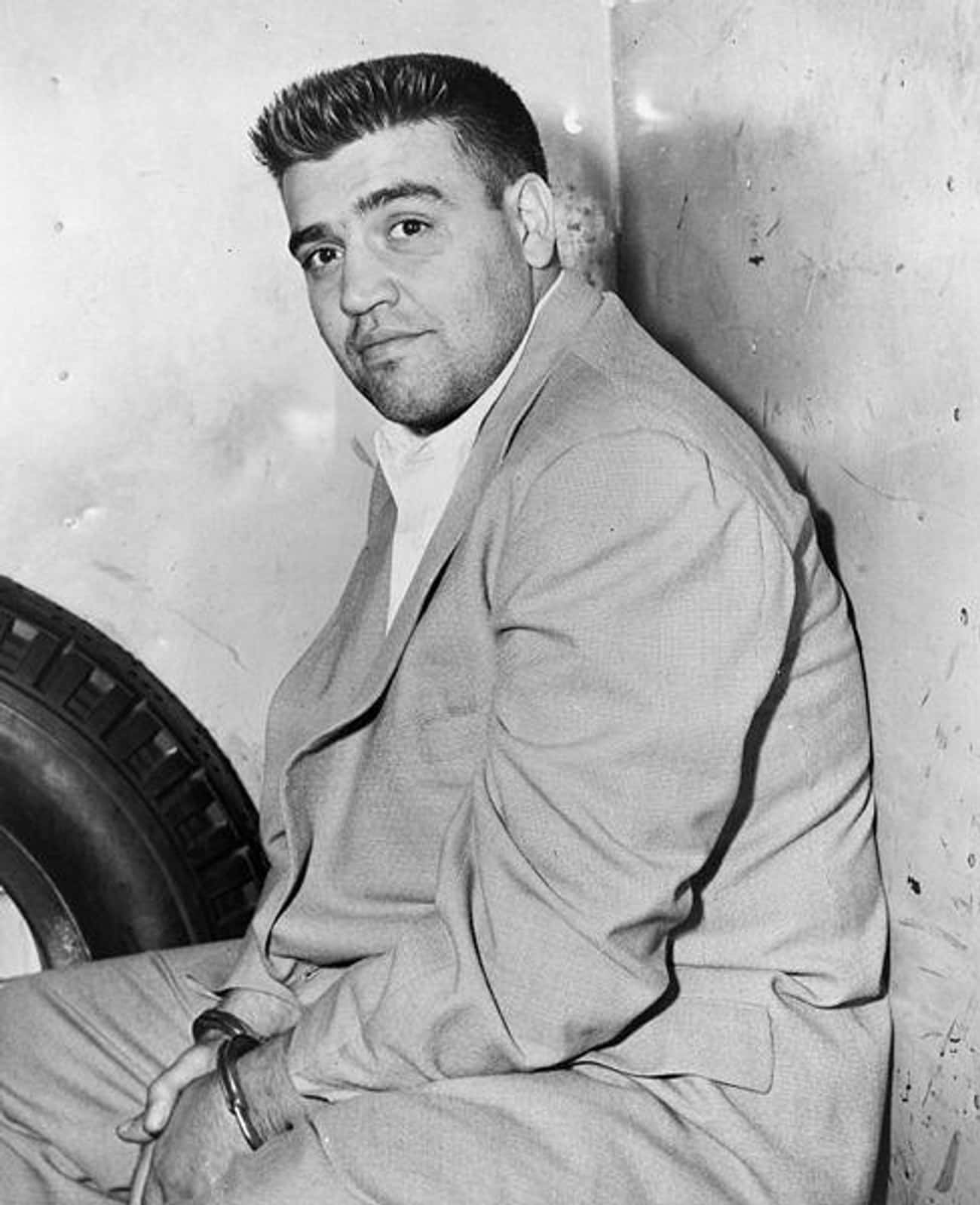

What Genovese didn't plan, however, was a raid by New York State Police. One year earlier, Bonanno family underboss Carmine Galante was pulled over in a car with fake license plates. That aroused suspicion by authorities in the area, who looked closely at Joe Barbara, Jr., already believed to be involved in criminal activities. As a result, they put the elder Barbara's house under surveillance. When a host of mafioso arrived there in November 1957, it was a boon for law enforcement.

The raid by the police rounded up more than 60 individuals, with another 50 men fleeing the scene. Many of the arrests were later thrown out, but some of the charges stuck. The most enduring thing to come out of Apalachin, however, was the unveiling of the National Crime Syndicate itself. J. Edgar Hoover, head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, had long denied the existence of such a body, but there was no longer validity to that claim. To make matters worse, a massive group of top leaders had met in one place without the FBI knowing about it.

- Photo: Cecil Stoughton / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

Hoover, Kennedy, And The Government All Set Their Sights On The Mafia During The 1960s

In 1951, a congressional investigation into organized crime headed by Senator Estes Kefauver brought numerous suspected mafioso to testify during televised public hearings. Of note was Frank Costello's testimony, described as intense with Costello twisting and clenching his hands while mumbling and defiantly dodging questions.

Overall, there was little in the way of legal change brought about by the Kefauver Committee. What it did accomplish, however, was “bringing public opinion to bear on the problems of interstate crime… [helping] local and state law enforcement and elected officials to aggressively pursue criminal syndicates [and demonstrating]… that some elected officials had facilitated and profited from criminal activities.”

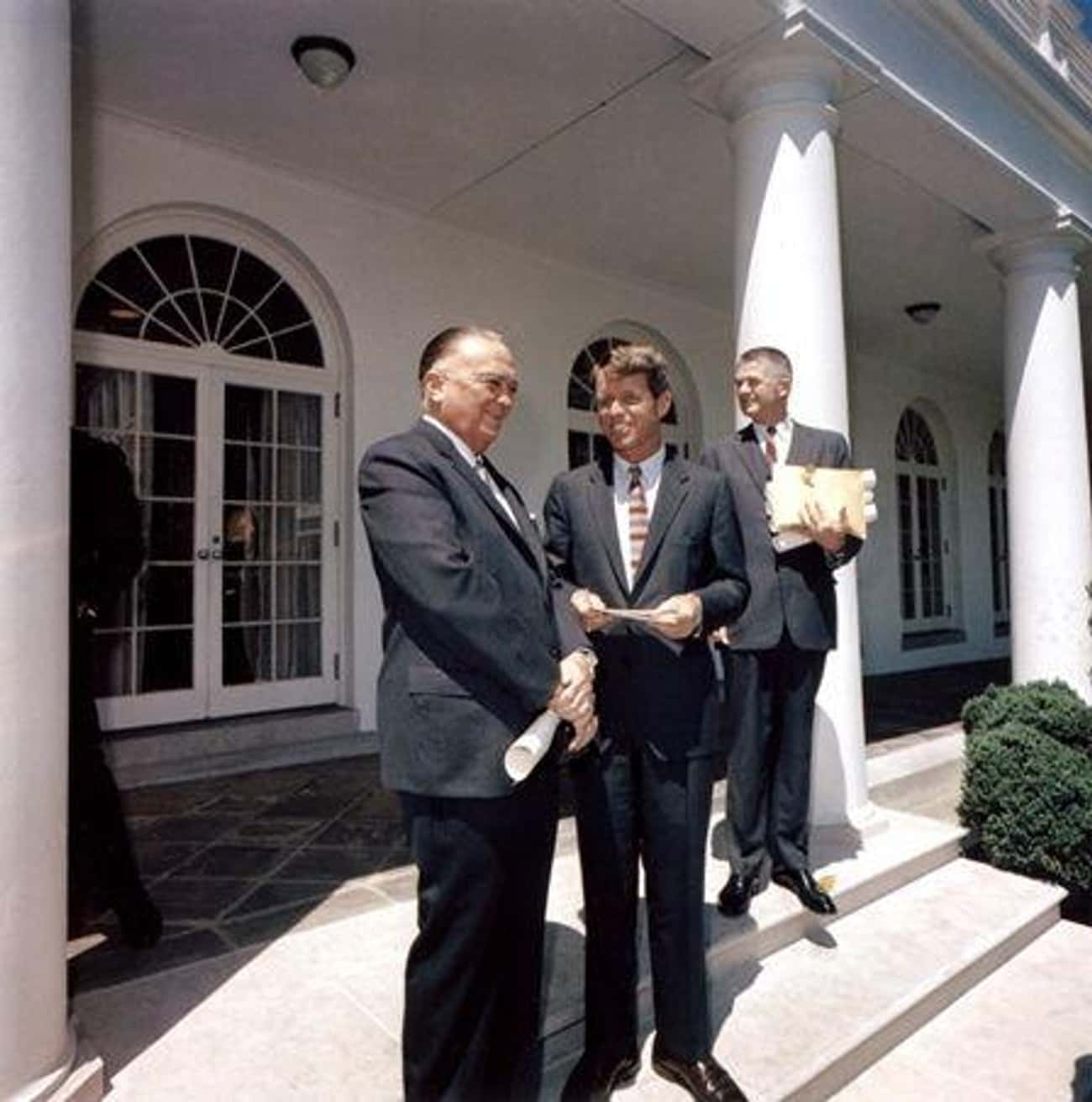

J. Edgar Hoover was against the creation of a Federal Crime Commission (as the Committee recommended) and continued insisting there was no national crime syndicate in the US. It was after Apalachin that Hoover and the federal government were forced to take action. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy tasked the Department of Justice with looking specifically at organized crime, and under his leadership convictions increased dramatically.

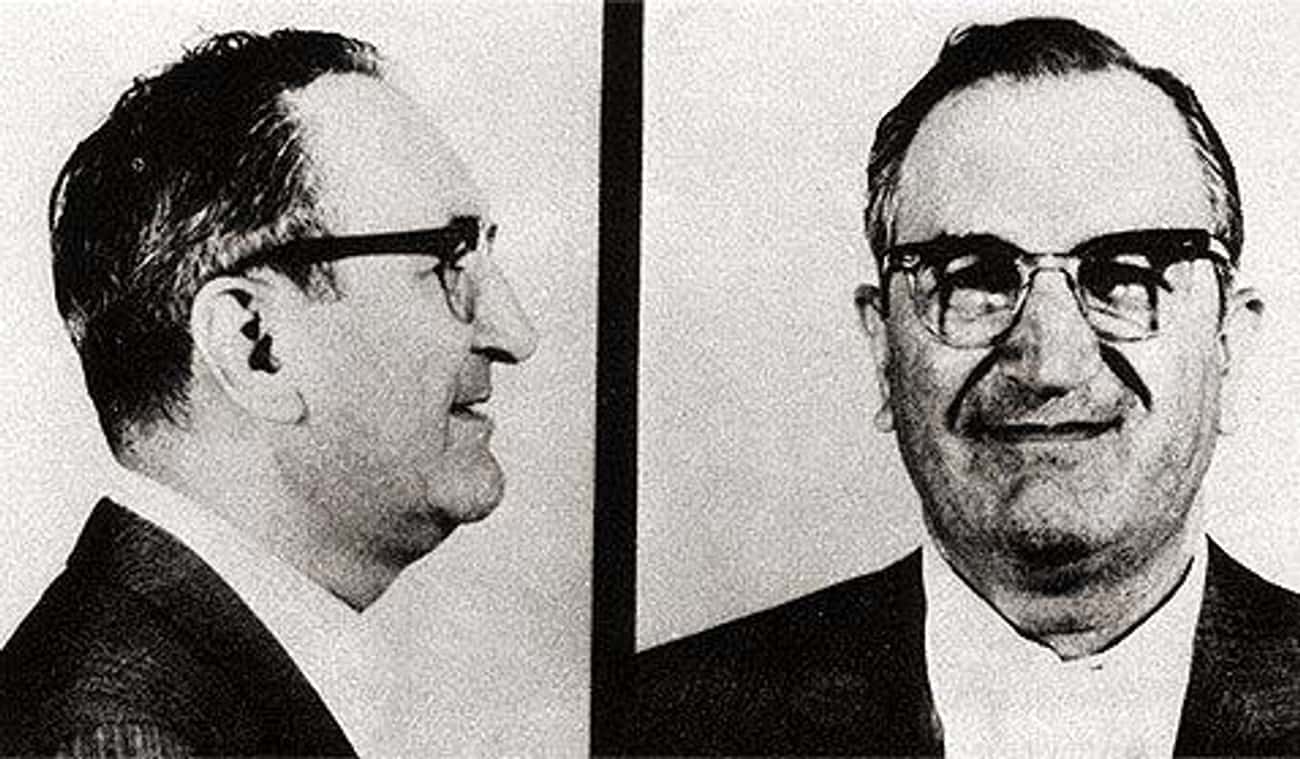

The biggest hit to the Five Families, specifically, came from the testimony of Joseph Valachi, a member of the Genovese crime family. Valachi appeared in 1963 to testify about organized crime and illicit narcotic trafficking and offered information about the innerworkings of Cosa Nostra, its organizational structure, and the illegal activities in which it was involved. That said, Valachi also contradicted himself at times and only presented the viewpoint of one single mafioso.

- Photo: US Federal Government / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

Bonanno's Disappearance And 'The Banana War' Signaled The End Of The Old Order

When Joe “Bananas” Bonanno, head of the Bonanno crime family, was abducted near his apartment building in New York on October 21, 1964, it essentially started the so-called “Banana War.”

Two years earlier, Joe Profaci, boss of the Colombo crime family, died, as did Lucky Luciano. The old guard was fading, and Bonanno's position was at risk, prompting speculation that Bonanno's disappearance was part of a larger plan to escape impending doom. Bonanno had recently decided to go on the offensive, putting hits out on bosses Tommy Lucchese and Carlo Gambino. After Lucchese and Gambino found out, they went to the Commission which then called Bonanno to answer for his actions. While Bonanno refused to appear, his partner in the plan, Joe Magliocco, told them everything.

Bonanno may have been ordered to leave or thought it was safer to do so. He was also scheduled to appear before a grand jury on the day he was kidnapped, another potential reason why he fled. If he was kidnapped, the theory is that his cousin and head of the Buffalo crime family Steve Magaddino was the man who kept Bonanno confined.

Regardless of how or why it happened, Bonanno's absence sparked war within his family. Bonanno was out as the boss and the competition for his successor was fierce. Bonanno had returned in 1966, but still meddled in family affairs despite promises to the commission that he'd stay out of them. In 1968, the war came to an end when Bonanno finally retired before permanently relocating to Arizona.

- Photo: Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

The Rise Of The Gambino Family Signaled A Shift In The Power Of The Five Families

Led by Vincent Mangano between 1931 and 1951, the Gambino crime family was headed by Albert Anastasia until 1957. From there, Carlo Gambino took over until he died in 1976. He was succeeded by his brother-in-law, Paul Castellano.

Castellano's rise to the top of the Gambino family came as a surprise to its members, especially underboss Aniello “Neil” Dellacroce. Two factions within the family rose, one that supported Castellano and one that backed Dellacroce, but they nominally agreed to work together to maintain the Gambino's rackets. This agreement fell apart after Dellacroce's death in 1985. Two weeks later, Castellano was murdered alongside his second-in-command Thomas Bilotti - killings ordered by Dellacorce's right-hand-man, John Gotti.

Gotti had long pushed back against Castellano's focus on less violent activities like loan sharking and union shakedowns. He favored more violent crimes like robberies, hijackings, and narcotics. With Dellacroce no longer around to keep Gotti from eliminating Castellano, that's exactly what Gotti did.

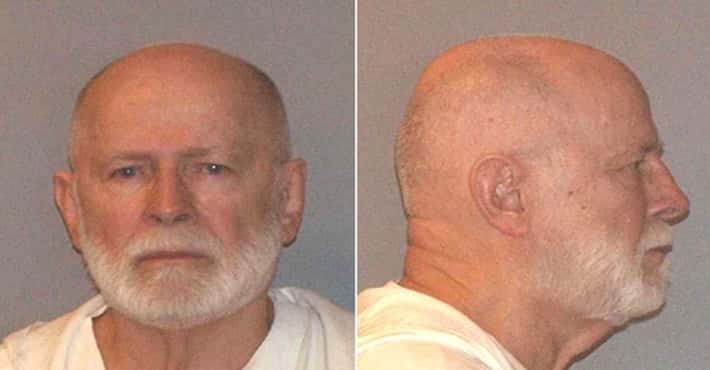

Once Gotti was in control of the Gambino crime family, he not only made it the most powerful of the Five Families but became a sensation outside of the world of organized crime. Gotti's high-profile trial for racketeering in 1986 resulted in an even higher-profile acquittal in 1987. Six of his associates were also acquitted, and, when the likelihood of the authorities coming after him next was mentioned, Gotti said to a reporter:

They'll be ready to frame us again in two weeks… In three weeks we'll be starting again, just watch.

Gotti's “Dapper Don” moniker, one given to him by the media for his expensive suits, quickly transitioned to “Teflon Don” as a result of how criminal charges didn't seem to stick to Gotti.

Gotti had outrun RICO (Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act,) the law passed in 1970 to “strengthen the legal tools in evidence gathering by establishing new penal prohibitions and providing enhanced sanctions and new remedies for dealing with the unlawful activities of those engaged in organized crime.” This didn't last long. Charged under the RICO statute again in 1990, Gotti was convicted of racketeering and racketeering conspiracy as well as on two counts of murder. He and his underboss Frank Locascio were sentenced to life in prison.

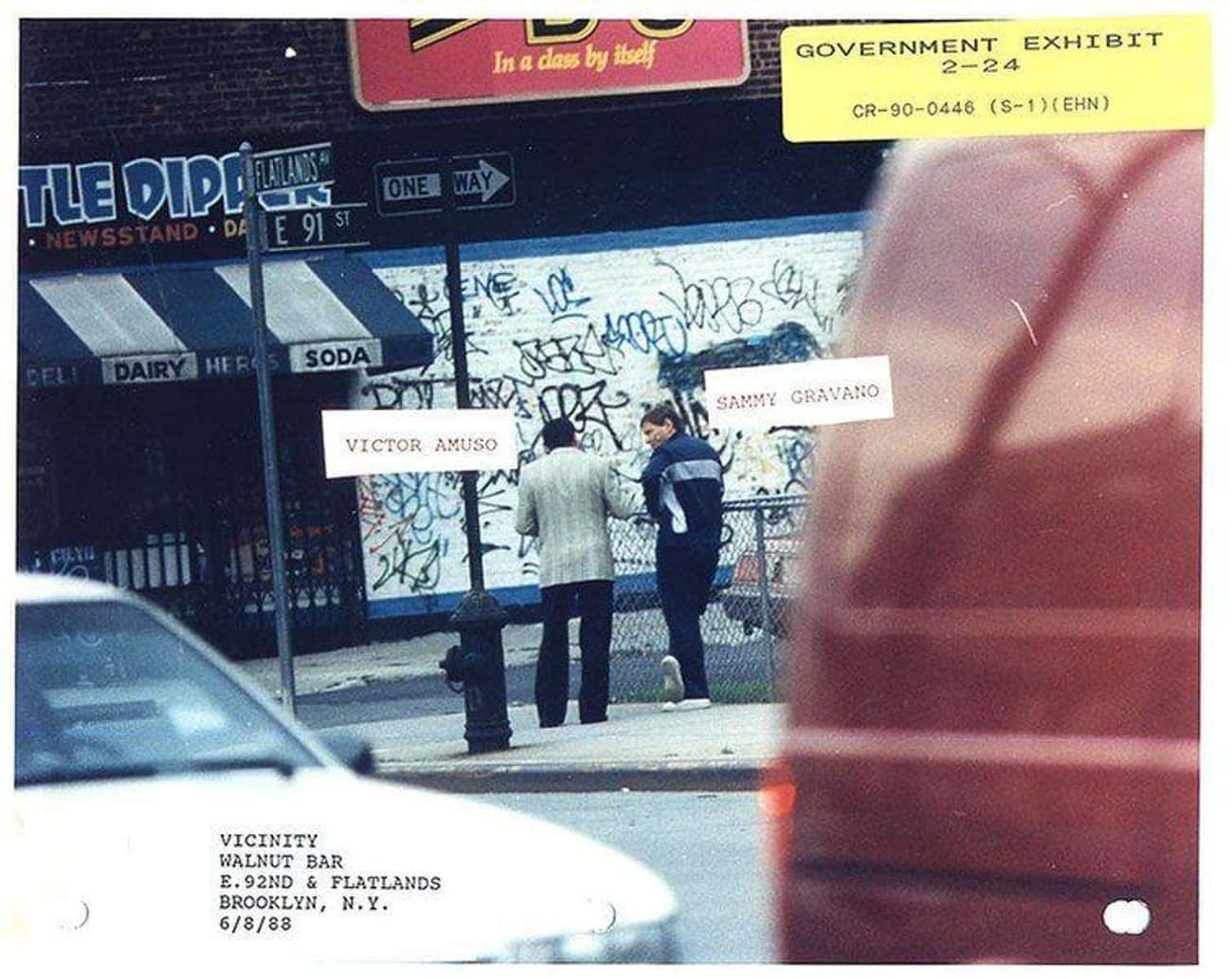

One of the key reasons for a change in Gotti's fortune was the testimony offered by Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano. Gravano had been arrested with Gotti and received a lesser sentence after turning on the boss.

- Photo: Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

Organized Crime And The Five Families Have Changed But Not Disappeared

While John Gotti had avoided RICO briefly, he was ultimately brought down by the statute - a demise that represented a shift that had already taken place in the world of organized crime. The Five Families peaked during the mid-20th century, and while they didn't vanish during the late 1900s, the power each family wielded changed.

As recently as 2011, the FBI apprehended dozens of “made” members of the Five Families and other Cosa Nostra groups, but Janice Fedarcyk, then assistant director in charge of the FBI's New York Field Office, noted:

Even more of a myth is the notion that the mob is a thing of the past; that La Cosa Nostra is a shadow of its former self.

Even former members agree. As Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano put it in 2023,

It’s totally different now… It’s more about making money but the quality control of the people has been lost. They don’t kill anymore, there’s no bodies popping up. They don’t kill nobody. How do you keep guys in line?

Additional factors in the overall changes that influenced the Five Families included, in the words of former FBI special agent J. Bruce Mouw,

The important, influential guys went to jail…. The bureau took away all the unions. The Gambino family had 10 to 15 unions that they controlled, construction, garbage collection. The unions made a lot of money for them. They may have a few now, but they are few and far between.

This largely came about because of RICO and the wide reach it gave authorities to upend criminal activities that were the purview of the Five Families. Mouw's comments came after Francesco “Franky Boy” Cali, the Gambino crime boss, was killed in 2019, however, an alarming killing that resembled an “old style” mafia hit. There were stark differences between how Cali was slain and many of those murders, however, given the statements made by the shooter, Anthony Comello, that he believed Cali was a “prominent member of the deep state, and, accordingly, an appropriate target for a citizen’s arrest.”