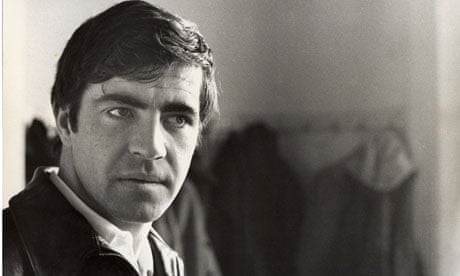

Sir Alan Bates, who has died after a long battle with cancer at the age of 69, was an actor of exceptional versatility. In a career spanning over 40 years, he triumphed equally in theatre, film and television. But his particular gift was for conveying a dangerous charm flecked with irony and, although he flirted occasionally with the classics, this quality was seen at its consummate best in the plays of Simon Gray, Harold Pinter and David Storey.

Bates was born in Allestree, Derbyshire; and, although Jane Austen's Elizabeth Bennet had "a very poor opinion of young men who live in Derbyshire", Bates made the most of its artistic possibilities. His father, an insurance salesman, played the cello and his mother the piano. And, apart from appearing in plays at his Belper grammar school, Bates became a regular visitor to Derby Playhouse, where he admired the work of two unknown actors, and later friends, John Osborne and John Dexter.

After RAF National Service and three years at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, where his contemporaries included Albert Finney and Peter O'Toole, Bates quickly found work with the Midland Theatre Company. But his big break came in 1956 as a founder member of George Devine's English Stage Company at the Royal Court in London.

He appeared in plays by Angus Wilson, Arthur Miller, Nigel Dennis and Wycherley. But it was as Cliff, the Horatio to Jimmy Porter's Hamlet, in Osborne's Look Back In Anger that he really made his mark. Playing the role on and off for two years, including a tour to Moscow and a run in New York, Bates had a shock-haired likeableness that made him an ideal foil to a succession of incandescent Jimmy Porters.

Osborne described Bates in rehearsal as "agreeable and bent on pleasing". But the dangerous side of his personality emerged when he played Mick in the initial run of Harold Pinter's The Caretaker in 1960. He brought out the protectiveness of the mercurial Mick towards his brain-damaged brother, Aston: what made one sit up and take notice, however, was his quiet intimidation of Donald Pleasence's tramp. Bates was the embodiment of Chaucer's "smiler with the knife under the cloak"; and it was this mixture of charm and menace that was to reappear throughout his career.

Success on stage led to a whole host of sixties films. He was a Christ-like hobo in Whistle Down The Wind (1961), a draughtsman forced into a shotgun marriage in A Kind Of Loving (1962), a prissy, poetry-reading Englishman in Zorba The Greek (1964), a Bathsheba-adoring shepherd in John Schlesinger's underrated Far From The Madding Crowd (1967). A hectic decade in movies was rounded off by a key role in Ken Russell's Women In Love (1969), where he enjoyed the dubious pleasure of wrestling naked in the firelight with Oliver Reed.

But, although Bates was a fine film actor, it was on stage that his particular quality of menacing mockery showed itself best. His 1970 Hamlet in Nottingham and London may have been a slight disappointment. But before that he was superb in David Storey's In Celebration at the Royal Court and when he played Simon Gray's Butley at the Criterion in 1971 there was a sense of a perfect marriage between actor and writer.

Gray's Butley is a waspish, self-destructive minor academic living in a permanent state of arrested adolescence. Under Pinter's direction, Bates brilliantly brought out Butley's blend of rancorous wit and emotional immaturity; and it was to be the start of a long and fruitful assocation with Gray that included the lead roles in Otherwise Engaged (1975), for which Bates won an Evening Standard Best Actor award, Stage Struck (1979) and Melon (1987).

If Bates was the quintessential Simon Gray actor, he was also an ideal interpreter of Pinter. He was outstanding as the tenant farmer in Joseph Losey's film of The Go-Between in 1970 scripted by Pinter. On television he appeared with Laurence Olivier and Helen Mirren in Pinter's The Collection, dealing with sexual power battles and mysterious events in a Leeds hotel room.

And in 1984 he created the role of Nicolas, the agent of state brutality, in Pinter's One For The Road. In his diaries, Gray commented approvingly on Bates's denial of his easy extravagance and flirtatious charm and called it "the most violent and hateful performance of his career".

The mystery of Bates's acting was that he never brought quite the same sense of danger to Shakespeare. He was a perfectly decent Petruchio at Stratford in 1973; but when I once asked his Kate, Susan Fleetwood, about the problems inherent in the play she replied: "What problems? Who wouldn't have fallen at once for such a gorgeous looking man?" Even his Stratford Antony a quarter-of-a-century later, going down on Frances de la Tour's Cleopatra like a cunning linguist, seemed mildly dissipated rather than recklessly obsessed.

But in contemporary drama Bates had few peers. In 1983 he was magnificent, both at Chichester and the Haymarket, as Alfred Redl in Osborne's A Patriot For Me: as a model soldier in Franz-Josef's Austro-Hungarian army blackmailed because of his homosexuality, Bates brought out the hero's ramrod-backed discipline and vulnerability. And there was more than a touch of Osborne about Bates's bravura performance in Thomas Bernhard's The Showman at the Almeida in 1993. In this two-hour near-monologue Bates played the fallen actor-hero forever ranting about being forced to work on tiny stages for lousy wages in front of philistines. It was a brilliant performance of a megalomaniac wreck.

If modern drama brought out the depth of Bates's talent, film and television exhibited his range. On screen he could be sexily charming as he showed in Paul Mazursky's An Unmarried Woman (1977), where he played a bearlike painter who attracts Jill Clayburgh's bereft heroine. As Pauline Kael wrote, "this is one of the rare occasions when a movie actor has simulated a painter so that you enjoy watching". On the small screen he was also an unforgettable Guy Burgess, strolling through the streets of Moscow to the sound of Gilbert and Sullivan, in Alan Bennett's An Englishman Abroad. And in Bennett's 102 Boulevard Haussmann he captured exactly the reclusive obsessiveness of Marcel Proust.

Jonthan Kent, who directed Bates at the Almeida, once said: "He has an air of mystery. There's an impenetrable heart to him." Even in interviews, he remained guarded about his life and talked little, if at all, about the tragedies that later afflicted him: in particular the death of his son Tristan from a freak asthma attack at the age of 19 in 1990 and the loss of his wife, Victoria Ward, from a heart attack only two years later.

After his son's death, Bates and his other son Benedick, Tristan's twin, established the Tristan Bates Theatre at the Actors' Centre in Covent Garden.

His other remedy was to throw himself ever more voraciously into his work; and it seemed only fitting that a remarkable lifetime's achievement was rewarded with a CBE in 1995 and a knighthood in 2003.

Bates was an infinitely versatile actor at home in all media; but what one will remember, especially in modern drama, is his matchless ability to suggest a quicksilver intelligence imbued with mischievous irony.

He is survived by Benedick.

· Derek Malcolm writes: The most famous - some would say notorious - scene from Alan Bates's screen career was the controversial nude wrestling sequence in Ken Russell's adaptation of D H Lawrence's Women In Love. Uncharacteristically, since he was an actor who usually rewarded his watchers in more subtle ways, Bates matched the macho Oliver Reed throughout the bout.

Neither actor was at all certain about performing the scene, being terrified, according to Russell, that one or the other's sexual equipment would not look adequate. But they both had a drink at the local pub to discuss the matter and, being comforted that neither was much smaller than the other, agreed to shoot the match. The shock caused by the sequence was considerable at the time, and even now it seems audacious.

This was Bates's most physical role.But his true forte was suggesting the inner turbulence of the characters he played, like that of Ted Burgess in Joseph Losey's The Go-Between or the intruder with Shamanic powers in Jerzy Skolimowski's The Shout (1978). His presence on the screen went far beyond either his looks or bearing.

Making his film debut in Tony Richardson's The Entertainer in 1960, he soon became not only a star of British cinema but also an international actor to be reckoned with. Schlesinger's A Kind Of Loving and John Frankenheimer's The Fixer, for which he received an Oscar nomination as best actor in 1968, saw to that.

His roles were many and varied and he was good enough to make something even of the more unsuitable ones like the romantic lead in Paul Mazursky's An Unmarried Woman or as Sergei Diaghilev in Nijinsky (1981). When he was good, he was very good indeed, as behoves one of the best actors of his generation - a performer of real substance, power and sophistication. All the best British directors coveted his presence in their casts.

· Alan (Arthur) Bates, actor, born February 17 1934; died December 27 2003.