Editor’s Note: Peggy Drexler is a research psychologist, documentary producer and the author of “Our Fathers, Ourselves: Daughters, Fathers, and the Changing American Family” and “Raising Boys Without Men.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are hers. View more opinion on CNN.

No, Republican Congressman Adam Kinzinger of Illinois is not exactly one of his party’s most progressive members. He opposes abortion and the Affordable Care Act. He supported the border wall.

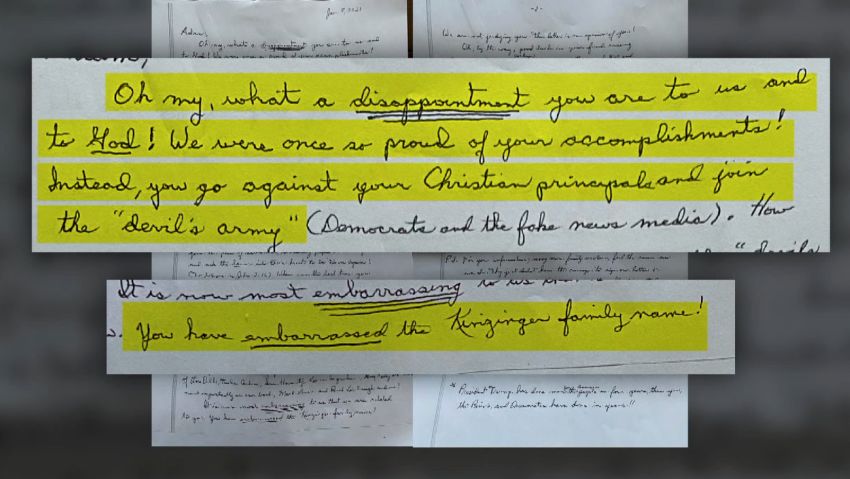

And yet, after he criticized former President Donald Trump for inciting the January 6 Capitol riot and called for his removal, a very conservative contingent of Kinzinger’s family declared themselves “thoroughly disgusted,” and called him a “disappointment… to us and to God.”

Maybe you’ve seen news of this unseemly family feud that the Kinzinger clan laid before the world this week. It came in a letter January 8, two days after the Capitol insurrection, and was reported by the New York Times earlier this week. Eleven of Kinzinger’s relatives signed on, rebuking him for making “horrible, rude accusations of President Trump,” and describing him as having joined “the devil’s army.”

They mailed the letter to Kinzinger’s father, and then, apparently, sent copies to members of Kinzinger’s party around the state, not only looking to make a point with their relative, but also to ruin him professionally.

“I wanted Adam to be shunned,” a cousin, Karen Otto, told the Times, which published the letter Monday.

Here is an extreme – and extremely public – example of a dilemma millions of Americans have faced over the past four years, where politics has gone far beyond differences of opinion and become totally and completely divisive – even, and maybe especially, among families. “It is now most embarrassing to us that we are related to you,” the letter read.

Kinzinger said he was not swayed by his family’s ire. After the letter, he went on to become one of 10 Republicans to vote to impeach Trump for “incitement of insurrection.” He told the Times: “I hold nothing against [my family], but I have zero desire or feel the need to reach out and repair that. That is 100 percent on them… and quite honestly I don’t care if they do or not.”

It’s no exaggeration to say that families have been ripped apart by the turn politics has taken, and that much of blame lies with the former president, a longtime spokesmodel for conflict over comity. And while there is hope that things will start to be better under President Joe Biden, the damage that the family-values-espousing Trump has done to the American family is going to be with us for a long time.

The upset among friends and relatives who may choose to never try to see the other’s side again is reflected in some arresting numbers from the Trump era in whose lingering grip much of the country, arguably, remains. According to a September analysis from the Pew Research Center, nearly 80% of Americans now have “just a few” or no friends at all on the opposite end of the political spectrum.

Partisanship is at an all-time high, Pew found in an earlier study, with the gap between Republicans and Democrats dwarfing gaps between people of different races, genders, religions, and education levels.

But even within parties – as Kinzinger now knows all too well – there are broad gulfs, often tied to age and generational differences. In its December 2019 analysis, Pew found that younger Republicans are more likely than older ones to say, for example, that humans contribute to climate change and that marijuana use should be legal. And about 80% of older Republicans see illegal immigration as “‘a very big problem’ facing the US; that compares with only about half (51%) of younger Republicans.”

Of course, public shaming does not have to follow such disagreement, and the Kinzinger clan seems remarkable in its willingness to air such a mean-spirited indictment of a family member. You can read the letter here. One hopes its extreme vitriol is as unusual as it seems – though these are difficult times, even politics aside.

It’s impossible to consider the tense political climate without considering that life itself, nearly a year into a pandemic, is tense –with anxious, fraught, cooped-up emotions ripe for explosion.

And yet, it’s the angry language we’ve gotten too used to, certainly, over the past four years –and the world we’re living in right now.

Does it have to be like this?

A 2019 survey published in the International Journal of Public Opinion Research found that the higher the conflict, the less likely it is that people will try to seek compromise. That is, our best bet at getting along is when there are low and moderate levels of disagreement, which is more and more a rarity.

Even among the scientific community, there is some dispute over how best to handle disagreement. Some research has suggested that disagreement increases ambivalence and decreases political participation – meaning that it causes less of a desire to even engage with others on issues, or even to vote. Other studies, including a 2017 Vanderbilt one, have suggested that most people want to talk about political issues with people of different opinions and that the failure to do so, even to do so in a heated way, is what leads to extremism and intolerance.

In fact, in normal times, most relationship experts agree that more conversation, not less, will help heal that which divides us. For many families, that may not work at this moment. At best, there’s frustration. At worst, found Pew, people who disagree are angry at or afraid of the other side, often both. The study, notably, was released just a few months before voters swept an uncommonly divisive president into office on a platform that elevated anger and fear.

And even though Trump was defeated in his reelection bid, much of that fear and loathing remains, as we can see with the Kinzinger family and many of our own, bolstered by the great fear, suspicion and alienation that Covid-19 has wrought.

What to do in such a scenario as it plays out in our everyday lives?

Get our free weekly newsletter

It’s OK to take a step back from a political conflict among family members, and not engage, and in the meantime hone in on your own beliefs – know that you’re standing up for a position you believe in, and not just one that reflexively runs counter to theirs because of their political leanings, be they Republican or Democrat.

As Kinzinger himself put it when speaking about his dissenters and choosing instead to follow his gut, “If you censure me for voting my conscience, that reflects more on you than it does on me.”

You needn’t accept their position, or even agree to disagree, but public shaming, Kinzinger-family-style, is definitely not beneficial, even if you think you’re sure right now you never want to repair the relationship. You may change your mind about that later, and it may be too late.

And, of course, always do your best to keep things kind – this is family, after all.