The Atom Bomb in Cinema: A look at 5 films from the 1950's-1990's

In 1945, George Orwell penned the concept of a “Cold War” in his essay “You and the Atom Bomb.” Orwell spoke on his anxieties around the splitting of atoms and their explosive capabilities. This was just two months after the abhorrent (there may never be a word quite strong enough) attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and 4 years before the Soviet Union had their first successful test of a nuclear weapon. His focus was pointed to the changes in the hierarchy of power these bombs will create.

Orwell argues that “the history of civilization is largely the history of weapons” and “that ages in which the dominant weapon is expensive or difficult to make will tend to be ages of despotism, whereas when the dominant weapon is cheap and simple, the common people have a chance.” He is pointing out the anxiety that the individuals must have because of a system they have no control over and have no way to retaliate against. Nuclear war/apocalypse films are so successful and resonant in the American psyche as they draw on these same anxieties.

This anxiety has persisted from well before Orwell wrote about it in 1945, but since the creation of cinema and the nuclear bomb are both relatively recent inventions, movies serve as a means to record the Atomic age and modern human’s struggle. This conflict against power and destruction can be seen in the decades since as films have grown to encapsulate other evolving fears. So, we are going to take a look at some seminal films of the Atomic Age to see that they may represent more than just the fear of annihilation but the relationship we have to the mechanism of power, as well as how that relationship has changed over the decades.

We may want to define the Atomic Bomb film. The films selected will focus on the characters' experience surrounding the research or activation of a nuclear weapon. This definition does not represent the totality of Atomic Films. For example, any film in the Godzilla Franchise would certainly be about atomic anxieties as the result of atomic detonation. However, The King of Monsters is the literal threat to the characters and not an atomic bomb. These films do not meet our purpose. Also, we will be looking specifically at American films, but I would like to point out that the entire world must have an opinion on “The Bomb.” The topic of atomic war is certainly not one for just the aggressors but also the victims. The nations of the world that were plagued and played with in a decades long Cold War and the entangled proxy wars have their own cinematic relationship with the Atomic Bomb that I would urge any reader to investigate. A great place to start may be in the director Akira Kurasawa’s filmography as these anxieties would influence him in making I Live in Fear in 1955, and then three and a half decades later, Dreams and Rhapsody in August.

We begin nearly a decade after the destruction of World War II with Kiss Me Deadly by Robert Aldrich.

Kiss Me Deadly (1955) by Robert Aldrich

Adapted from the 1952 novel by Mickey Spellman, this noir film was released to much controversy. The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) called the original script “totally unacceptable” for its “numerous items of brutality and sexual suggestiveness.” It stars Ralph Meeker as Private Investigator Mike Hammer. The character is derided as a mere “divorce dick” by the police, while in the novel is herald as a competent P.I. Aldrich and screenwriter A. I. Bezzerides made this change to show Hammer as a more cynical figure.

Kiss Me Deadly is a film about a vengeful man stuck in the middle of two large forces: the mob who is dealing in nuclear energy and the state trying to cover-up the horrors of nuclear power. He feels that he has a responsibility to find the perpetrators of a heinous murder but his investigation leads to more questions. Like Oppenheimer, upon discovering his mistake in investigating and flying too close to the sun, Hammer shares the similar belief that he had “become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” The film is a master class in dread and anxiety by keeping the atomic harm hidden until the last moments of the picture. Ultimately, Kiss Me Deadly leaves the audience thinking about how they too occupy the space between the same two bad actors perpetrating the emerging Cold War and it may be best not to look too much into it. We, like Hammer, can ultimately do very little when going up against such powerful forces.

Fail Safe (1964) by Sidney Lumet

In the same year as Dr. Strangelove (or the film that gave us the format for making jokes about the bomb), Sidney Lumet released Fail Safe, a film about how our atomic procedure and perhaps human empathy may be hijacked by bureaucracy and ego. In the effort to handle the threat of World War III, the President and his advisors have to try and disarm the threat of nuclear war while being the exact perpetrators of this violence. Stanley Kubrick actually sued the production and forced its release after Dr. Strangelove because the plots were so similar. But make no mistake, this film is not a comedy.

Fail Safe is positioned as reality. With no score and stark black and white photography, the film depicts a world in which the powerful are actively against the little people. Their power corrupts them into a belief that they have been elevated above to make the most important decisions. As an audience member, you can feel from the first minute you are not in the room. You are purposefully kept out of the room. All that matters is the fact that several years ago you participated in democracy. I would like to point out that this wasn’t a ballot proposition. There was no “Vote No to Nuclear War” yard sign next to your “In This House We Believe” sign. There were only those who had power already asking for even more. Fail Safe is a study of this power and how officials choose to wield it. I would say the true horror I felt when watching this was not how little power I had to change it, but in how even though I believe it should be different, I don’t have the energy to try in the face of overwhelming odds.

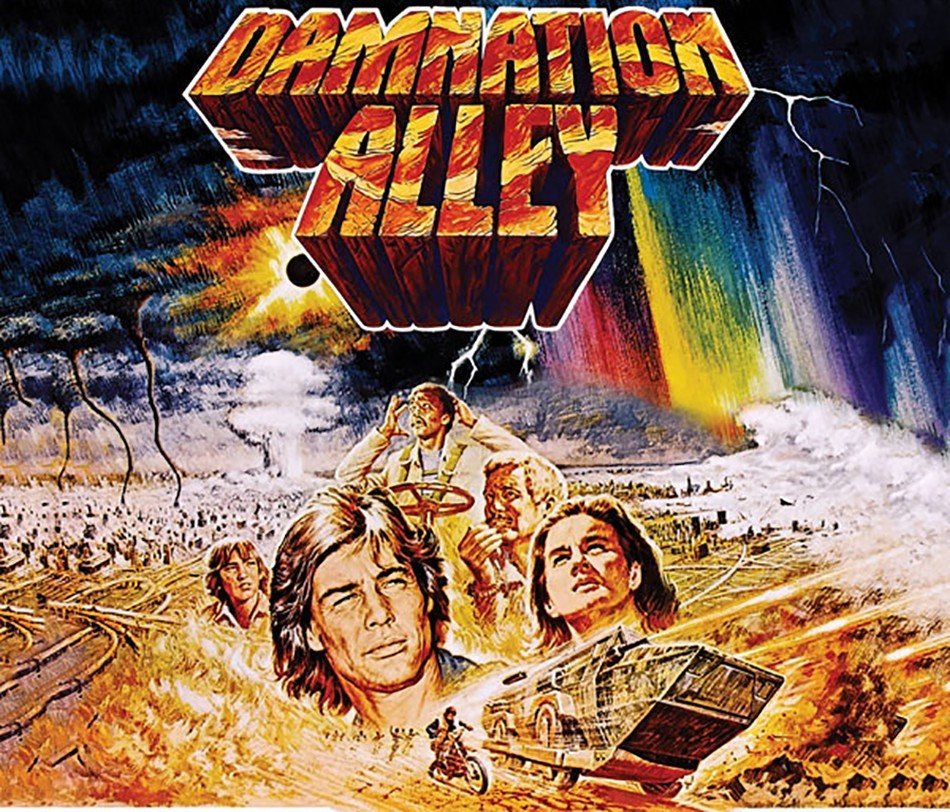

Damnation Alley (1977) by Jack Smight

The 1970’s would not be considered the height of the Atomic Cinema. Only 4 films were released in direct concern to the dropping of atomic warheads. These would be Glen and Randa (1971), A Boy and His Dog (1975), and Damnation Alley (1977). In 1979, The China Syndrome was released, which seemed to be a match for the 80’s boom of atomic cinema, though about conspiracy and malpractice at a nuclear plant, not atomic war. Smight’s Damnation Alley is a seemingly low-budget road film (with an actual budget of 8 million, this was Fox’s money making bet against Star Wars) about a crew of ex-Air Force officers trying to get to Albany, New York after the bombs have dropped. This journey is mired with conflict with scorpions the size of motorcycles, man eating cockroaches, and wasteland bandits. While certainly not a film I would recommend due to its poor preservation and special effects, it does give insights to Hollywood's perspective on the human struggle after nuclear annihilation.

The only things that thrive in this wasteland are pests. The characters argue about the purpose of military service after the end of the world while people in the theater had been drafted. The film is most interested in pointing out the silliness of the current time in which characters make impassioned speeches on freedom and the right to expression in an uncaring world. I would say many of these 70’s era films are trying to do the same. The nuclear wasteland has little difference from the 1970’s landscape but has higher stakes when trying to survive a colony of radioactive scorpions.

Miracle Mile (1988) by Steve De Jarnatt

After forty years, the threat of nuclear power was about to wane. Though possibly hitting its peak in 1983 due to a Soviet false alarm, Reagan goes on to sign the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, and Bush Sr. is there when the Berlin Wall is torn down. The 80’s were a prosperous time for many. This dwindling of atomic anxieties with the headlines of peace and prosperity is where we meet Miracle Mile in 1988. Love rises to the top in this romantic thriller with some great acting from Anthony Edwards. Miracle Mile also excels in its dialogue and visual metaphors to elevate it above the other Atomic Bomb films of the 1980’s. This is the boom of nuclear films in American Cinema as the Cold War overstays its welcome. With the decline of the Soviet Union and a perceived victory for capitalism, it becomes less stressful to talk about. Now we can see the “good guys” win.

Ultimately, Miracle Mile is a film about being at the right place at the right time when so often we feel that fate has led us astray. Budgets for Atomic Films grew as the blockbuster was elevated by James Cameron and George Lucas. They brought Sci-fi into the mainstream, with The Terminator and Star Wars but Miracle Mile remains special with its focus on the everyman at street level. Harry (Edwards) a jazz trombonist has finally found The One but in missing his date due to an exploding pigeon's nest, he believes he has messed it all up. He tries to find Julie (Mare Winningham) but her shift ended hours ago. While trying to contact her, Harry intercepts a call warning of the nuclear attack on Los Angeles. Harry is able to organize an escape plan but must find Julie so that he can truly be happy. Miracle Mile shifts the characters' concern away from the threat of annihilation and to personal gratification. Now, our basic needs include love. The characters aspire to live on high and pass into heaven but like so many of us they end up in the depths of hell. We can only hope to have love with us to make this existence tolerable.

Matinee (1993) by Joe Dante

Whelp, it’s over folks. The Republicans in office have taken part in de-escalation and summits with Gorbachev (not to mention proxy wars in Lebanon, Granada, Nicaragua, and The Iran-Contra Scandal.) Reagan and Bush Sr. have ridden the dissolution of the Soviet Union into times of peace. As much as peace can include a US stockpile of nearly 11,000 warheads to Russia’s 37,000. So, the Hollywood nuclear film becomes nostalgic with Joe Dante’s Matinee. Starring John Goodman as a film producer who is essentially William Castle, Matinee focuses on the town of Key West during the Cuban Missile Crisis and the premiere of “Mant!” This B-movie with every gimmick packed into the theater entices Gene, a horror obsessed teen. While “Mant!” is the almost stereotypical atomic thriller with bad science and rubber mutations, Dante’s film is a sincere look back at the B-Movie era of the 60’s and 70’s. An era when people could seemingly escape the fear of nuclear annihilation by going to the movies. It’s meta-narrative looks at why people congregate at the movies and how exposure to the things you fear in the dank cave of a Key West movie theater may help alleviate the stress of the real world.

The Atomic Film has continued up to our modern day but producers seem happy for these subjects to fall further into the backdrop. Nuclear annihilation is now thwarted by just one man (namely Ethan Hunt) or perhaps merely represented by a space alien that snaps so hard people turn into dust. The Cold War is over and there isn’t just one bad guy with all the weapons in the world. Now, it’s distinct cells with specific leaders that we outgun and still end up killing more civilians than we expected to. Yet, movies about anxieties of the populace continue to surround the idea that there are those more powerful than us. Those who we can’t really fight against and we have to trust they will fight for us. In watching all these films, I can’t help but think that Miracle Mile has gotten it right. One day, you will get a call that says your time is up and no matter how much you have planned, investigated, or seen, it would be best to just have somebody to hold at the end of it all.

Forest graduated from the University of Texas at Austin hoping to make the world a better place. So far, he has just been watching movies and writing about them. That’s the same thing, right?