“I acknowledge that our laws failed to recognise the cultural heritage and rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for many decades and the dispossession and disempowerment this caused.”

“Legal history as has often been said, is the history of ideas. But ideas are not self-sown. They are coloured by environment and conditioned by the climate of opinion; but they are, after all, the creatures of men’s minds and to isolate them from the pressure of personality, even if it were desirable, is impossible.” These words by Justice Michael Kirby addressed the legal history of Australia but such could ring true for the NSW Supreme Court, which this year marks its bicentenary. What lessons from its past will shape its future?

The year is 1824. The first free press in Australia, enacted without government approval, was introduced in Hobart. The US Presidential Election, a contest between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, is forced into a deadlock broken by intervention in the House of Representatives. After some tense negotiations, Russia agrees to reopen its Pacific ports to US ships, laying the groundwork for the first treaty concluded between the two countries. Just three years have passed since the death of Napolean Bonaparte. It is the year that Beethoven’s First Symphony premieres in Vienna and that New York City’s Fifth Avenue opens for business.

In May of that year, the Sydney Gazette published these words, announcing the founding of a court now renowned around the world as one of the most enduring in common law jurisdictions:

“The formal promulgation of His Majesty’s New Charter of Justice, took place at noon, on Monday last… At two o’clock .. this court opened.. At three, the Charter was proclaimed in the Market-place. .. His Excellency the Governor entertained his Honor the Chief Justice.. at dinner- in honour of a day that will long be remembered by the grateful inhabitants of Australia.”

It was a time when the live-streamed justice of today’s court proceedings would have seemed unimaginable: perhaps something akin to the work of H.G. Wells, the science fiction maestro whose late 19th century works foreshadowed concepts like air and space travel, nuclear weapons and the internet. Yet throughout its history, the Court has been a beacon of stability and enduring order. Its resilience feels more pertinent than ever, in an era of declining trust in institutions and the easy spread of misinformation.

“As I point out to new lawyers on their admission, in a world in which there is much global uncertainty and insecurity, the rule of law is more important than ever and not simply an academic construct or a phrase of some mere theoretical import. At its simplest, it is the opposite of the arbitrary abuse of power and the rule of autocratic dictators and populists,” Chief Justice Andrew Bell said when addressing a sold-out crowd at the NSW Opening of Law Term dinner on 31st January.

“I am continuously impressed to see and or learn of the work of so many lawyers in social justice initiatives, pro bono endeavours, educational work and contributing to diverse community organisations, over and above their day jobs, as well as those involved more directly in the important work of the Law Society and Bar Association, and their committees.

“The 200th anniversary of the Supreme Court is a milestone worthy of celebration, but it is not a celebration for celebration’s sake. It marks 200 years of continuity of the rule of law in New South Wales.”

The year marks one of great change for the courts in NSW, as both the Chief Judge of the NSW District Court, Justice Derek Price, and the Chief Magistrate of the Local Court of NSW, Judge Peter Johnstone, will retire from their posts in coming months.

Yet it will also be 12 months of reflection and examining the evolution and changing face of justice in the state. The NSW Supreme Court will host a number of bicentenary events to mark 200 years since its founding under the Third Charter on 17th May 1824. It has since flourished as one of the longest continually running courts in the common law world. Yet a peek inside its early history reveals moments when its foundation was shaky.

“The rule of law does not exist in a vacuum, and the Court’s vivid history animates it,” Chief Justice Bell said in his Opening of Law Term address.

“That history, replete with famous cases and some large personalities – litigants, advocates and even judges – also provides a unique lens into, and is intimately interwoven with, the social, economic and political story of the colony, and then the State, of New South Wales. As the Sydney Morning Herald editorialised on the occasion of the Court’s centenary in 1924, to study the Court’s history “is to study the growth of our nation.”

Early Beginnings: the Charters from penal colony to properly established Court (1787-1824)

When the First Fleet arrived on Sydney’s shores, civil and criminal courts were established for New South Wales by Letters Patent, known as the Charter of Justice of 1787.

Free residents of the colony signed petitions to introduce jury trials and for more than 20 years, successive Governors tried to have the constitution of the courts improved to ensure that justice would be guaranteed to all classes in the infant colony. One teething problem was a lack of qualified legal practitioners.

In 1809 a mild concession was made by the Colonial Office in London who appointed a barrister, Ellis Bent, as the first legally trained Deputy Judge-Advocate to the colony. But his proposals to introduce trial by jury and to reform the system of criminal trials were rejected by the British Government.

The colony’s Deputy Judge-Advocate, David Collins, who had no legal training, sat with several naval or military officers to hear criminal matters. It was run much like a court martial, and in 1788 hanged the first of many colonists, for theft. Many more followed for what would today be considered misdemeanors. Sitting with a bench of two “fit and proper” residents of the colony appointed by the Governor, Collins also heard and decided civil matters.

Unfortunately, his successors’ battles with the Governors of the Colony and other prominent residents, along with the many abuses of power which came to light during the following years meant the early courts were held in low esteem.

In 1814, two new courts were established under the Second Charter of Justice to hear civil matters. Their limited scope did little to boost the quality of justice or ease the ongoing troubles with administration.

“The rule of law does not exist in a vacuum, and the Court’s vivid history animates it. That history, replete with famous cases and some large personalities – litigants, advocates and even judges – also provides a unique lens into, and is intimately interwoven with, the social, economic and political story of the colony, and then the State, of New South Wales.”

In order to examine the fledgling problems, London barrister John Bigge was appointed as the Commissioner and dispatched down under to investigate many workings of the colony, including the running of the justice system. Bigge acknowledged the need for grand and serious reform in order to improve Australian’s burgeoning administration, including with a new court system.

This proposed new court, modelled unsurprisingly after the English judicial system, adopted the principles of Common Law and Equity, laying the foundation for a legal framework that would evolve over the next two centuries. It would also require the appointment of a Chief Justice.

The Third Charter of Justice paved the way for both the founding of the NSW Supreme Court and also the NSW Legislative Assembly. The basis of that Charter still shapes how civil and criminal cases are heard today. At that time, jury trials were introduced in civil matters, with free settlers to make up the juries, although army or naval personnel still formed juries to hear criminal matters.

On the 17th May 1824, the proclamation of section 18 of the New South Wales Act of 1823 in the Parliament of Westminster following on from the Bigge report, authorised, in the words of Chief Justice Bell “the issue of letters patent in the form of the Third Charter of Justice.”

Sir Francis Forbes, who had been responsible for drafting the legislation that gave birth to the Supreme Court, was appointed the state’s first Chief Justice. He read out the Charter in the Georgian School in Elizabeth St, Sydney, to the west of the St James Church. The reason for the location was because, at that time, debate and disagreement marred the decision making as to where the Court would be housed.

‘No need of fancy buildings’: the making of the King St court complex

Its checkerboard tiles and chequered list of high-profile accused have long made the King St Courts an iconic stop on a tour of the Sydney legal precinct. Its ornamentals finishings and eye-catching staircase are attractive features, yet this famed building came to life as a renovator’s nightmare.

According to the NSW Court history website, in July 1813, Governor Lachlan Macquarie, mindful of the need for a court house in the heart of Sydney, argued Magistrates of the colony should convene to commence a public subscription for the building of “a respectable court house and town hall under the one roof.”

With that ambition in mind, Governor Macquarie opened the appeal to construct the court with a gift of £500 from colonial funds and a generous personal gift from his own funds of £60.

The end target of the appeal was £5,000, enough to construct a “plain substantial building of suitable size and respectable exterior appearance”, without going for unnecessary costly architectural design. Governor Macquarie had just the man in mind to meet the specifics of this particular job: He engaged Australia’s first architect DD Mathew to propose a design for how the court house would take shape. Unfortunately, few of the settlers shared the official enthusiasm — four months later the appeal was abandoned, and Governor Macquarie decided unwillingly that if he was to have a court house it would simply have to be built with convict labour.

As often occurs in significant architectural works, including the Sydney Opera House more than a century later, the gap between artistic vision and approved budget placed the project at risk. When the time came to present the plans, mapping out a two-storey building with two wings and a Doric portico, Governor Macquarie dispatched them to London to Earl Bathurst, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, along with a request for the necessary funds.

As the Court’s history website describes it; “funds were denied for ‘penal colonies had no need of fancy buildings’ was the reply.”

Thankfully, all was not lost. Resurrection of this vision came six years later, on 7th October 1819, when Governor Macquarie confirmed the construction of “a large and commodious court house”, during the same visit to Australia by Commissioner Bigge to examine the legal workings of the colony. In modern political parlance, the Commissioner appeared to give the project the green light, with a lighter budget. This time the court house was to be designed by a convict architect Francis Greenway who had been transported to Australia for acts of forgery.

Less than six months later, Bigge had experienced a change of heart. He wanted the court to be a church instead. A month later, he then demanded that a proposed school, the Georgian Public School for neglected children, be replaced by a court instead. In the haste to bring one of these projects to completion, some crucial mistakes were made; including the roof of the school-turned-court being built before supporting infrastructure, like braces and pillars.

In 1827, Chief Justice Forbes and colleague Justice John Stephen moved into the Elizabeth St side of the building, while construction continued on the other side. There followed several years of disagreements with builders and alarm at visible structural flaws, including cracks in dividing walls, poor ventilation and an overly smoky fireplace that could not be used when the wind blew in certain directions. Nevertheless, construction persisted, at a time when the courts were dealing with a skyrocketing caseload across both common law and equity cases, and more than 300 people coming through the doors daily. To handle the chronic overcrowding, a series of disparate additions and extensions were made to the building, to mixed results.

In 1848, changes were made to the chambers of Chief Justice Stephen to solve a dampness problem, but the judge moved out the following year, saying the continued damp had given him a rheumatism attack and ruined a treasured collection of law books worth £1000.

For decades to come, judges would hear cases to a background thrum of traffic and construction noise.

The King St Court was fully unveiled at the opening of the 1896 law year. The building was described, according to the court’s history as “bright and pleasant, quiet and comfortable”.

The transformative years (1824-1900)

The early decades of the 19th century saw the Supreme Court grapple with the ongoing challenges of a growing colony. Judges like Sir Forbes and Sir James Dowling navigated complex legal issues, from land disputes to criminal trials that would shape the legal landscape of New South Wales.

Chief Justice Bell believes the celebration of the Court’s history year is reason to reflect on its role as “a vital organ” in “the functioning of democracy.” He references a quote from the state’s fourth Chief Justice, Sir James Martin, who said in a judgment delivered in 1880: “A Supreme Court like this … is the appointed and recognised tribunal for the maintenance of the collective authority of the entire community. The enforcement of all those rules which immemorial usage has sanctioned for the preservation of peace and order, and for the definition of rights between man and man, is entrusted to its keeping.”

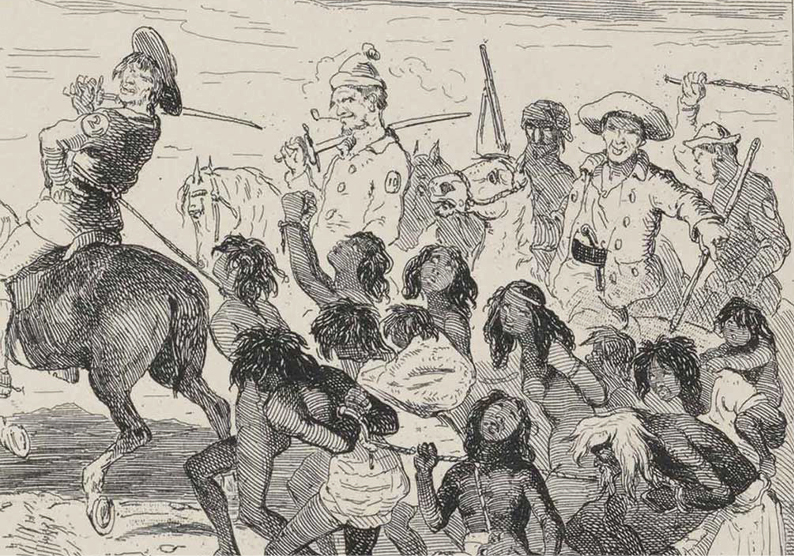

Yet the shadow and impact of one landmark early trial still lingers today. On the 10th June 1838, the Myall Creek Massacre took place, a crime which became the first matter of its type to be heard by the Supreme Court. The facts of the case make for horrifying reading: as many as 30 Aboriginal people were murdered at Myall Creek near Bingara in Northern NSW. A great number of the victims were women and children.

Myall Creek locals reported the crime, including the station manager William Hobbs, leading to the arrests of 11 men over the murders. Those men were put on trial in the Supreme Court but the jury, who believed the Aboriginal people were a menace to settlers, found them not guilty. The case was sent for retrial, and this time seven men were found guilty of murder by a jury. Their sentence was to be hanged.

The main witness to the crime, Aboriginal man Yintayintin, mysteriously disappeared before the trial of the last four men, the result being that they were never tried. It is suspected people knew where the twelfth man (a free settler) accused of murder lived but he ran away and was never arrested.

Many in NSW at that time were more outraged by the execution of British citizens than they were by the brutal massacre of the Wirrayaraay people. After the seven men were executed, many in the community felt even more hostile towards Aboriginal people. Violence against and murders of Aboriginal people continued.

The gold rush of the 1850s brought a surge in litigation, leading to the establishment of the District Court in 1858 to handle cases of less complexity. In 1858, the District Court Act established a lower court, lessening the Supreme Court’s workload and making justice more accessible for the residents of the colony of NSW.

“NSW was the last state to introduce divorce in 1873, following the passing of the Matrimonial Causes Act. Stemming from this, limited divorce jurisdiction was granted to the Court in 1873, followed by full Admiralty jurisdiction in 1911.”

The latter half of the 19th century saw a period of transformation and modernisation within the court. It was also a new era of judicial activism and legal reform. Martin’s tenure saw the adoption of progressive legal doctrines, including both the recognition of equitable principles and the expansion of jury trials.

Changing social norms also resulted in the court witnessing advancements in its jurisdiction. NSW was the last state to introduce divorce in 1873, following the passing of the Matrimonial Causes Act. Stemming from this, limited divorce jurisdiction was granted to the Court in 1873, followed by full Admiralty jurisdiction in 1911.

Modernisation and Reform (1900-Present)

The 20th Century brought about transformations for the Supreme Court in nearly all respects; and yet it has maintained continuity with the Court as it was founded by the Third Charter of Justice in 1824. This is a rare feat in Common Law jurisdictions, where most courts have been drastically reshaped and reformed.

“There have, of course, been changes in the manner in which the work of the Court has been conducted although, in truth, and at the most fundamental level, these changes have been minor,” the Chief Justice said in his Opening of Law Term address.

“Core features of our judicial system throughout the Court’s history, such as procedural fairness, hearings in open court and reasoned judgments delivered by impartial judges, secure in their tenure and thus guaranteed independence, are central to the working of our broader democracy under the rule of law.”

In 1912, the New Supreme Court Act reorganised the court structure, creating separate Equity and Common Law divisions, which were intended to reflect the ever-growing complexity of legal matters. This separation, however, was short-lived. After the Court was re-organised (but its original identity was preserved) by the Supreme Court Act 1970 (NSW), in 1972, the court underwent a historic fusion. The Common Law and Equity divisions were merged into a single and unified Supreme Court, which continues to operate to this day.

This unification served to streamline Supreme Court proceedings and brought greater coherence to the legal system in NSW. For the first time one Court over saw the whole tradition of English common law.

A surging NSW population, and the legal disputes that grew with it, warranted the need for physical expansion.

In 1976, the construction of the Queens Square Law Courts building was completed; an imposing 27-storey, 33,000 sqm building that also contains courtrooms for sittings of the High Court and Federal Court. The jewel in its crown is the Banco Ceremonial Court on level 13, which will be the heart of one of the planned bicentenary celebrations. The Queens Square complex has had a less colourful history than the chaos of the King St creations. A product of the brutalist school of architecture of its time, the building has remained strong and steadfast, with just one refurbishment in 2009 and one dramatic flooding event in September 2023.

The use of juries continues to be a bedrock of the Supreme Court, despite the challenges an 800-year-old system can face in a time of hyperconnectivity and widespread social media and online accessibility. The NSW Government is currently considering changes to the jury system, including cutting down the deliberation time before a majority verdict can be accepted. Currently, the Jury Act 1977 requires a criminal trial jury to sit for at least eight hours before a court can permit them to reach a verdict in which a single juror’s opposing view is able to be disregarded. The Law Society of NSW’s submission on the Jury Amendment Bill 2023 argued that the rationale for the eight-hour minimum has not changed since the measure was introduced in 2006.

Sequestering of juries—the practice where the jurors are not dismissed at the end of each sitting day but rather stay in organised accommodation for the duration of the trial—remains extremely rare in NSW. The last time a Supreme Court jury was sequestered in NSW was in 2015, during the third trial of the accused Lin family killer, Lian Bin ‘Robert’ Xie, accused of murdering his brother and sister-in-law Min and Lily, two nephews Henry and Terry and Lily’s sister Irene as they slept inside their North Epping home.

The trial had spanned more than nine months and the arrangement allowed the jury to continue their deliberations after hours, inside the conference room of a CBD hotel.

It’s absolutely critical at this stage that you have a focused and concentrated aptitude to the evidence and all that it gives rise to,” the trial judge, Justice Elizabeth Fullerton, told them.

“It’s with your concentrated and focused attention that your verdicts will be reached in the best way possible.

“You’ll be fed … [and] there will be an alcohol allowance … I haven’t decided on the size of that allowance yet, however I won’t be mean-spirited.”

Unable to reach a verdict, the jury was discharged. A retrial held the following year resulted in an unanimous guilty verdict on all five charges against Xie, who later unsuccessfully appealed against his convictions.

The (short) history of women on the Bench

While the court still has much modernising to do when it comes to gender and racial diversity, its history shows some impressive judicial dynasties. Since 1930, three generations of the Street family—Sir Philip Whistler, Sir Kenneth Whistler and Sir Laurence Whistler—have served New South Wales as Chief Justice.

The make-up of today’s Supreme Court bench reflects great gains in a relatively recent window, but there are many appointees needed before the Court reflects the changing legal profession, where women lawyers have outnumbered male lawyers for some time.

The first woman appointed to the Supreme Court was Justice Jane Mathews in 1987. Justice Mathews was a two-fold trailblazer, having also been the state’s first Crown prosecutor and also the state’s first-ever female Judge when she rose to the bench of the NSW District Court in 1980, before her fortieth birthday.

Upon her death in September 2019 aged 78, Justice Mathews was lauded for her enduring commitment to social justice over a career spanning six decades.

“She was able to articulate issues very succinctly, whether that be in her legal work or whether that be in respect of the wider issues in the law that she considered important – most particularly, the position of women in the law and what needed to be done in respect of their advancement,” NSW Governor Margaret Beazley told the Sydney Morning Herald following Justice Mathews’ death.

As Chief Justice Bell noted in his address at this year’s Opening of Law Term dinner in Sydney, “The second female judge of the Court, my friend, the wonderful and wise Carolyn Simpson AO, will finally retire from the Court in March of this year, just shy of its 200th anniversary. That the second-ever female judge appointed to the Court is retiring on the cusp of its 200th anniversary speaks for itself.”

“However, the role of women in the profession has changed greatly and is continuing to change. More than two thirds of practitioners under the age of 35 are female, as are almost 45 per cent of the State’s judicial officers,” the Chief Justice said.

It was only 25 years ago when Supreme Court Judges Carolyn Simpson, Margaret Beazley and Virginia Bell made headlines as the three sat together in the Court of Criminal Appeal in Sydney on 16 April 1999, the first time in Australia that the appeal bench had been comprised solely of women judges.

Today, the state’s second-highest ranking Judicial officer is Justice Julie Ward, the President of the NSW Court of Appeal. Justice Ward’s career has been one of ‘firsts’. She was the first female solicitor appointed directly to the bench of the NSW Supreme Court in 2008, sitting in the equity division. She later became a Judge of Appeal in 2012 and then the Chief Judge in Equity in 2017.

Justice Ward believes there is still “a long way to go for women in the profession.”

“But I do think the glass ceiling has been broken in a lot of the areas that women would be willing to practise,” she told a Law Society International Women’s Day event last year.

“Looking at the court that I am in, we aren’t much closer to achieving gender parity, if at all, than we were when I started,” she said.

“On the Court of Appeal, we have three female judges, so that means statistically you have [one] woman on the bench most often. Occasionally we will have benches that are all female. But it would be better if we had more women in the divisions.

“Everyone is conscious of the need to have diverse representation, but the issue is not so much now with gender parity, but with diversity in other areas of the bench too.”

Televising (and tweeting) justice

The past 15 years have seen the barriers between the courtroom and the community tumble down in a storm of tweets, podcasts, and live streaming of proceedings.

Whilst some in the judiciary remain critical of the simplified or sensationalised coverage of cases, believing the nuance of a decision is lost in the chase of a good headline, others believe the public now has a stronger-than-ever understanding of the court’s responsibilities to the proper administration of justice.

The Supreme Court joined Twitter in 2013, the same year as the almost five-hour verdict in the judge-alone murder trial of Simon Gittany, convicted of killing his fiancée Lisa Harnum by throwing her from the balcony of their 15th floor apartment. The case was one of the first in NSW to have its own hashtag (#Gittany) with the Tweets from journalists covering the case spreading across the world, providing an insight into the watertight judgment of Justice Lucy McCallum.

In September 2014, the NSW Government passed the Courts Legislation Amendment (Broadcasting Judgments) Bill 2014, making NSW the first state in the country to grant a presumption in favour of a camera crew filming a sentence or judge-alone verdict. This has enabled scores of sentences to be filmed and broadcast, allowing the public a greater understanding of the way Judges reach their decisions and the many factors they must consider.

The digital transformation of the court took on greater urgency following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. In August of that year, then Chief Justice Tom Bathurst delivered a YouTube address for new solicitors who, after years of study, were unable to have the traditional court admissions ceremony.

“You would be more familiar watching cat videos, beauty tutorials or food hacks on YouTube, rather than your admission ceremony. This is as strange for you as it is for me. I didn’t know what a vlogger was until last week, but I guess I am one now,” Justice Bathurst said.

Chief Justice Bathurst

Chief Justice Bathurst

The address was not only meeting the moment of supporting young lawyers in a scary moment of the pandemic. Chief Justice Bathurst also reflected on the Black Lives Matter movement which was at that time sweeping the globe in the aftermath of Minneapolis man George Floyd’s murder by a police officer.

“As lawyers, we are called upon to ensure that our justice system is in fact just for all,” Justice Bathurst said.

“The Black Lives Matter movement has brought the racism, inequality and abuses of power that have haunted our nation for so long to the forefront of public consciousness.

“I acknowledge that our laws failed to recognise the cultural heritage and rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for many decades and the dispossession and disempowerment this caused.”

He also stressed that the face of legal profession must strive to better reflect the community it serves.

“I am the first to admit that there are more people that look like me in senior positions in the law than look like anyone else in the community,” he said.

“Systemic barriers, inappropriate workplace behaviour and prejudices continue to hinder women and those from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds from fully and equally participating in the legal profession. This must change.”

In 2022, Justice Ian Harrison found Chris Dawson guilty of the 1982 murder of his wife Lynette in a comprehensive verdict spanning several hours, and broadcast to thousands, with more than 25,000 people tuning in for the final moments of the Judge’s lengthy and considered decision, most of them fans of the record-breaking podcast The Teacher’s Pet.

200 years young: a cause for celebration

When the Honourable Andrew Bell was sworn in as Chief Justice on the 8th March 2022, the bicentenary celebrations were among the topics raised in his speech, alongside “reviving the personalisation” of court procedure as more and more doors reopened following the pandemic.

“Whilst the remote practice of law may be possible, it is far from desirable. The administration of justice is best served in open court for reasons which are profoundly important,” he said.

The 2024 President of the Law Society Brett McGrath told this year’s Opening of Law Term dinner the legal profession is “very excited” to be part of the Court’s milestone and thanked the Chief Justice for his support of the shared history between the two bodies.

“We are a profession that stands over 40,000 strong, and the privilege of leading the solicitor branch, through such exciting and challenging times is humbling,” McGrath said.

“Looking forward, we face many challenges — legal technology, the wellbeing of our profession, and the evolving role of lawyers in society.

“[But] together as a united profession, with our diligence and precision, we can continue building a legal system that upholds the rule of law and defends the rights of all.”

The Court has announced three initiatives so far to mark its milestone birthday.

The first is an expansive book celebrating the bicentenary history of the Court, edited by the former President of the NSW Court of Appeal Keith Mason and legal researcher Larissa Reid. Entitled “Constant Guardian: Changing Times: The Supreme Court of New South Wales 1824-2024”, the work is a 450-page richly illustrated account., and was launched on 3 April 2024 by the 16th Chief Justice, Jim Spigelman, in the lead up to a ceremonial sitting on 17 May 2024.

With the support of the Legal Profession Admission Board, every new lawyer admitted to practice this year after 17 May 2024 will be presented with a copy of the book. The book is available for purchase.

At the suggestion of Supreme Court Justices Dina Yehia and Michael Slattery, the Court will also offer Indigenous students or young practitioners, an opportunity to have an internship with a Supreme Court judge.

This program will be integrated into existing initiatives with Legal Aid NSW, the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions, the NSW Public Defenders Office and many private law firms.

“There are some outstanding Indigenous lawyers in our profession, but they are far too few, and a great burden is placed upon them,” Chief Justice Bell, the state’s 18th Chief Justice, said in his address.

Inside the Queens Square complex, a new history wall, providing a chronological timeline of the Court with pictures and memorabilia, has been built outside the Banco Court, where ceremonial sittings and swearing-in ceremonies take place.

Just Chat: The Chief Justice of New South Wales Andrew Bell joins the Just Chat team for a wide-ranging conversation about the celebrations to mark the bicentenary of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, AI and the judiciary, as well as the launch of “Constant Guardian” – a rich and detailed history of the Court.

Just Chat: The Chief Justice of New South Wales Andrew Bell joins the Just Chat team for a wide-ranging conversation about the celebrations to mark the bicentenary of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, AI and the judiciary, as well as the launch of “Constant Guardian” – a rich and detailed history of the Court.