History's Weirdest Death Sentence Rules You Never Knew Existed

It's 1386 and you're a Frenchman in the Norman city of Falaise. A high-profile murder trial of a killer sick enough kill a young child is ending. As you sit in the courtroom, the judge pronounces a sentence: the defendant is to hang. The only problem? The defendant is a pig.

This isn't an absurdist film — it's a real trial illustrating that the administration of the death penalty — something people take for granted as a fact of life in the past — has been far from simple and sometimes downright weird. Given humans' morbid fascination with death — especially when it becomes a public ritual — it is no surprise that capital punishment developed all sorts of rules and customs that rarely make sense to modern Western audiences.

Nevertheless, recall Chesterton's Fence: if a long-standing tradition exists, it's probably there for a reason. Ditto for the sometimes-Byzantine rules surrounding capital punishment; they made sense in their historical and social contexts — sometimes practical, other times ritualistic, no matter how repulsive they might seem today. The only thing they have in common is that they were usually downright brutal.

Asking for forgiveness

Despite their fair share of cruel and unusual punishments, medieval and Renaissance societies tried to blunt the impact of the death penalty by turning it into a more "humane" Christianized ritual. This involved getting the executioner and the condemned together for a last drink and a plea for forgiveness.

The execution of Hans Vogel in 16th-century Nuremberg, as recounted in historian Joel Harrington's book "The Faithful Executioner, reproduced in Slate, illustrates the elaborate — and sometimes strange — ritual that developed around the death penalty. The condemned man's last days were not too dissimilar from a death row inmate's final days today. He could receive family, receive spiritual comfort, have a last meal and drink, and confess his sins in hopes of getting into heaven. But once it was time to die, his final meeting would be with the executioner, who walked into the condemned — and ideally, drunk — man's cell dressed in his best clothes.

Once inside the cell, the executioner would ask the inmate's forgiveness for what he was about to do. They would then engage in small talk — or at least try — and figure out if the prisoner was ready for the execution. If not, they shared a St. John's Drink, the famous painkiller, and proceeded to the execution site. If the executioner was feeling merciful, he might let the condemned man take a comfort item to the execution.

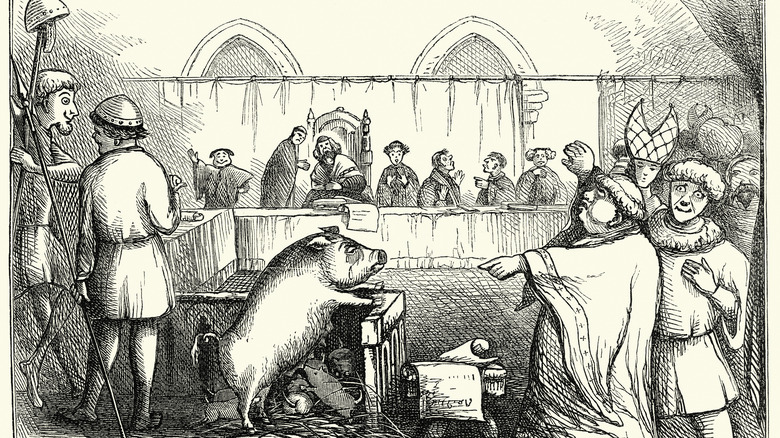

Animal trials

It's 1457. A sow and her six piglets terrorize the French town of Savigny, attacking people and killing a 5-year-old boy. According to JSTOR, instead of facing liability, the pigs' owner walks, leaving the animals to stand trial for murder. The sow is convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. The piglets walk on the basis that no one could prove their involvement.

It's unfathomable to modern ears, but this kind of thing really happened, and not just in Savigny. As previously mentioned, in 1386, another sow was executed on similar grounds in the Norman city of Falaise. Animal trials saw their defendants accused of crimes like murder and tried as humans, even though they could not defend themselves because, well ... they were animals. So when the sow of 1386 was executed, she was dressed up in a human's clothes, taken with an armed escort, and hung by a professional executioner.

Surprisingly, trying animals over demonic activity was rare, likely because the medieval Catholic Church generally did not prosecute witchcraft. Usually, people took those matters into their own hands, as in the killing of black cats during plagues. Cases like the execution of the Cock of Basel were the exception. The bird was executed for laying an egg that would hatch into a basilisk (like the one in Harry Potter).

Tipping the executioner for a less painful death

Across Europe, especially in pre-Revolutionary France, execution varied according to one's class. Commoners faced some of the most painful methods of execution such as burning, hanging, or being "broken on the wheel" — an excruciating punishment that involved crushing the condemned man's bones and threatening them through the spokes of a wheel before being stabbed. Aristocrats were also technically subject to such punishments. But even at death's doorstep, money talked. Among the unwritten rules of execution was the chance for the wealthy to "tip" the executioner to get a less painful death by beheading. During the French Revolution, the revolutionaries bemoaned this fact and decided to equalize things by inventing the guillotine, which would subject all the condemned to a quick death by beheading.

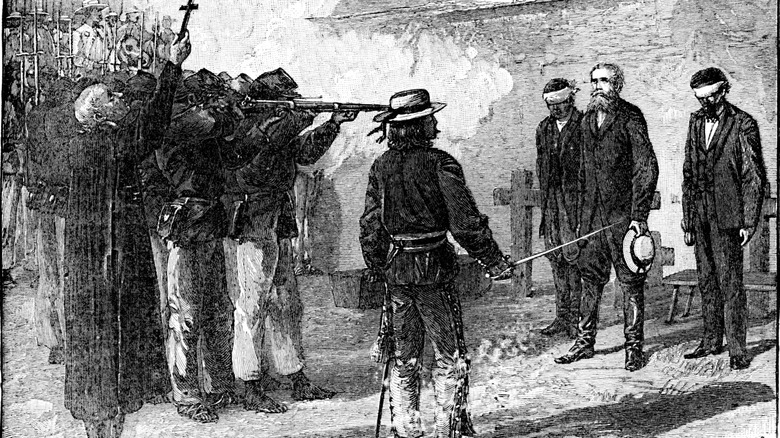

Although Europe abandoned the more brutal forms of execution in the 19th century, the practice of tipping executioners did not die out, mostly in the context of firing squads. At least one example of this exists from 1867, when Emperor Maximilian of Mexico faced the firing squad at the hands of Benito Juarez's Mexican republicans. The Met Museum says he gave his executioners some gold to grant him a more dignified death by not shooting him in the face. It is unclear what really happened, but given the commonality of the practice among European nobles, there's no reason why it couldn't be true.

The Law of Fratricide

Imagine a law that requires the death penalty regularly — not just a one-off — to be applied to a group of people just for existing. That is how things worked in the upper echelons of the Ottoman Empire, where all male claimants to the Sublime Porte were de facto sentenced to death under the Law of Fratricide.

The Ottoman Empire had one achilles' heel that no army could counter: the sultans' practice of polygamy. The vast Ottoman harems birthed numerous potential successors to the throne, resulting in succession crises every time a sultan died. Instead of instituting a clear succession law, Mehmet II, whose first act was to kill his infant brother, passed the Law of Fratricide. This legislation legally required the sultan's heirs to fight it out and kill all of their male siblings and all of their uncles and cousins with claims or designs on the throne until only one man was left.

The law was brutal and its logic simple: no spares meant no civil war or internal unrest. The Hunger Games-style free-for-all ensured that the most ruthless and sadistic men became sultans — men who were willing to keep the diverse and fractious Ottoman Empire united and their positions secure by any and all means necessary. Brutal to Western eyes, but in the context of the dangerous world of the Renaissance, it made sense from a purely realpolitik perspective.

Aztec alcohol laws didn't care who you were related to

Generally, the more money one has, the more one gets away with, especially when it comes to crime. Even history's most famous law code, that of Hammurabi, gave nobles a free pass on a number of capital crimes for commoners. In the Americas, however, things were very different.

The Aztec law on public drunkenness best illustrates this point. The Aztec Empire strictly controlled alcohol consumption. Only the elderly could drink freely and still show their faces in public — it was even encouraged at certain ceremonies. Otherwise, alcohol was virtually forbidden to commoners, while elites were allowed to drink in limited amounts. But being part of the ruling class was not a get-out-of-jail-free card for violating the law. Public drunkenness was a capital offense for anyone under 70 — and it did not discriminate. Nobles and commoners alike who appeared drunk in public were given second chances, but repeat offenders went straight to execution.

The Aztec rationale for punishing nobles the same as commoners rested on the empire's conception of nobility. As the educated class and future leaders of the empire, nobles set the standards for public virtue and conduct — in other words, they were expected to practice what they preached. The only difference was the execution itself — commoners were publicly beaten, while nobles and their families were spared shame through private strangulation.

The Catch-22 of Dakota justice

A functioning justice system ideally punishes wrongdoing rather than encouraging more of it. Among the Dakota people of the Upper Midwest, however, punishing the crime of murder was hardly straightforward, thanks to a Catch-22 of sorts that put family honor on a collision course with justice.

Being a non-literate culture, the Dakota and most other native tribes of North America did not have written law codes. Justice was often meted out by elders or sorted out among the families of those involved in a dispute. Because of this system, feuds between Dakota families — particularly those involving murder — often got out of hand. After the initial murder occurred, custom dictated the aggrieved party seek vengeance, which often culminated in a cycle of revenge killings that stacked several more bodies and created several more murderers to avenge.

Eventually, the elders would tire of the ceaseless killing and negotiate between the killers' family and the victims' family. The murderers' family would agree to turn the accused over to the victims' family. If the original killer was already dead from a revenge killing that had been perpetuated, whoever did the most recent revenge killing was handed over to the victims' families instead. That family can then decide to kill him or set him free. This method was perhaps meant as a deterrent — if one carried out the revenge, they became a candidate for execution; a true Catch-22 if there ever was one.

Among the Inuit, relatives carried out executions

The nomadic Inuit of the Arctic did not have any concept of law or tit-for-tat justice as the sedentary societies in Europe, Asia, and Mesoamerica did. Rather, crime was defined principally on whether the action was considered detrimental to group survival. Punishment was meted out according to the level of disruption, which the Alberta Law Review calls the "maintenance of peace."

A handful of offenses were considered so noxious to collective survival that they usually resulted in execution. Some of them were typical — serial murder (single murders could be excused in the name of group harmony), serial lying, serial theft, or mental illness, and sorcery. Other "crimes" related to group survival included being an extra, unwanted (usually) female child, being elderly, or chronically ill — and the Inuit way of administering justice was simultaneously strange and extremely cruel to modern eyes.

Under Inuit custom, relatives of the condemned party carried out the execution. This undoubtedly was incredibly difficult — imagine being a mother asked to abandon her baby daughter, or a man told to kill his elderly relative. But within the Inuit value of collective survival above all else, the rules made sense in the harsh Arctic, unity was paramount. Disunity through internecine feuds could mean the destruction of the group and all its members. But if the people closest to the condemned person carried out the killing, there was no one to take vengeance on.

In Japan, executions are quick, unexpected, and sometimes unappealable

In countries such as the United States, death row inmates are often given spiritual counseling, visits with relatives, a last meal, and notice of their execution well before it ever happens. Opponents of the death penalty argue the long wait (usually while pleading for clemency) is psychological abuse. Japan, however, has solved this problem by making executions sudden and unexpected.

Japanese executions follow a different set of rules than what Americans might be used to. They are carried out by hanging, whereas in the U.S., they are usually by lethal injection or gas. In Japan while one can appeal a capital sentence, the execution can be carried out even while a retrial is pending. Condemned people in Japan usually learn their fates on the mornings of their executions. Their families only find out about the execution afterward from a Ministry of Justice press release.

Death penalty opponents have accused Japan of torturing inmates mentally by hitting them with news of a death sentence unexpectedly and on short notice, without any chance to have family or other friends present for comfort. Japan, on the other hand, has defended this practice as an act of mercy towards the condemned, who would suffer from dread while waiting to be executed.

Stonings in ancient Israel were community affairs

Scholars assume the laws of ancient Israel drew from the three law codes preserved in the Pentateuch, or the first five books of the Bible. If so, stoning would have been the most common penalty for a battery of offenses ranging from adultery, idolatry, blasphemy, and violating the Sabbath.

Leviticus 24:16 says such executions were community affairs, "The whole community shall stone that person" for blasphemy of God's name, with witnesses casting the first stones. The Law's reasoning comes down to purity and collective atonement. The commission of a serious sin brought impurity and guilt upon that person's family and community. By taking part in the sinner's execution, the community purged itself of guilt and impurity. In cases of adultery regarding non-virgin brides (rape excepted) on their wedding nights, Deuteronomy 22:21 called for the men of the community to stone the guilty woman at the entrance of her father's house. Again, the logic ran that executing her there would "Thus ... purge the evil from [their] midst" and return honor and purity to the family home.

It is unclear how the secular laws derived from the law worked in practice, since no legal records or statues from ancient Israel have survived. However, it is reasonable to assume that if the Pentateuch, whose origin is ascribed to God himself, was already around by the 10th century B.C., its rules would have been reflected in the penalties of the time — even if not perfectly.

Venice's secret executions

As the Reformation reached the Italian peninsula, the Republic of Venice faced a dilemma. The republic needed to enforce Catholicism without risking its reputation as a tolerant place for anyone — irrespective of religion — to do business. This was by necessity; the merchant republic's wealth depended in part on relations with Protestant Northern Europe and an influential Jewish community for commercial contacts and opportunities in the Muslim-ruled Eastern Mediterranean. Fighting Protestantism through the Papal Inquisition risked retaliation from Protestant trade partners.

According to historian John Martin's "Venice's Hidden Enemies," La Serenissima settled on the adage that if no one saw it, it didn't happen. While Renaissance heresy executions were usually public displays of deterrence, Venice avoided execution whenever possible. While the government did mete out death sentences, and publicly executed "common criminals," when it came to heretics they carried out those killings in absolute secrecy. A small group of officials and priests rowed the condemned person out to the lagoon before sunrise, weighed them down with a stone, prayed over them, and dumped them into the water. No body, no witnesses, no evidence. For all the doge knew, the condemned person had simply skipped town.

With secret executions, Venice could tell its Protestant partners with a straight face that no persecution was happening to those who didn't subscribe to Catholicism, tell the pope the exact opposite, and send a warning to other potential heretics in her midst that if they went too far, they might just disappear without a trace.

Sherbet and races at the Ottoman court

While members of the Ottoman imperial family were subject to the Law of Fratricide, official executions of non-royals were far more ritualized. According to historian Godfrey Goodwin (via Smithsonian), executions were announced by the sultan's head gardeners. The potential victim was summoned. "[H]e had to bite his lip through the courtesies of hospitality before, at long last, being handed a cup of sherbet. If it were white, he sighed with relief, but if it were red he was in despair, because red was the color of death." Members of the elite janissary corps then killed the unfortunate man. Given one political slip-up could earn the sultan's ire, Ottoman bureaucrats dreaded this ritual.

For the highest-ranking officials — namely the grand vizier — there was a chance to escape the dreaded red sherbet. If the official could defeat his assigned gardener in a foot race, he would escape execution. The custom survived into the 19th century, with the last recorded instance being the victory Grand Vizier Halil Pasha. This man, whose predecessor was executed nine days into the job, won his race and a job as governor of Damascus.

Mongol executions could not shed blood

The Secret History of the Mongols, a 13th-century biography of Genghis Khan, narrates that in his earlier days on the Mongolian steppe, he captured two chieftains who had betrayed their oaths to him. They gave themselves up and fully expected to meet a bloody end by having their throats slit. Instead, Genghis Khan had them suffocated to death. This method of execution seemed a glaring contradiction to the usual Mongol modus operandi: leaving a bloody trail of destruction and dead after sacking their way through their latest victim.

The trend seems to be that the Mongols were happy to shed blood when killing common people, but when it came to nobles, other rules applied. Hulegu Khan, for instance, had Abbasid Caliph Al-Mu'tasim rolled in a carpet and trampled to death by horses during the 1258 sack of Baghdad, while Khwarezmian governor Inalchuq was executed with molten silver down his throat. Translator Urgunge Onon explains that the Mongols were superstitious about shedding the blood of nobles and preferred to kill them through other ways — usually by trampling.

It is unclear why the Mongols had this superstition. One possibility is that it gave royalty a noble death, although not necessarily a less painful one.