- India

- International

How the Islamic revolution isolated Iran from the Muslim world

As tensions between Israel and Iran escalate, reports indicate that a number of Arab states are aligned closer towards Israel than Tehran. Since the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the Muslim World has had a rocky relationship with Iran. From the First Gulf War to the Sunni-Shia divide, seminal differences exist between Tehran and their Gulf neighbours.

The Revolution of 1979 changed the face of Iranian foreign policy (Wikimedia Commons)

The Revolution of 1979 changed the face of Iranian foreign policy (Wikimedia Commons)“We have no decision to build a nuclear bomb but should Iran’s existence be threatened, there will be no choice but to change our military doctrine,” said Kamal Kharrazi, an adviser to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

His comments came a month after Israel on April 13 faced a barrage of 300 missiles and drones directed towards its territory from Iranian soil. Jordan helped fend off the attack, and according to reports that it later denied, so did several other Arab states. Despite their unwillingness to accept credit for Israel’s defence, Israeli leaders along with observers in Washington pointed to this incident as being indicative of a larger rearrangement in Middle Eastern politics.

An anti-missile system operates after Iran launched drones and missiles towards Israel (Reuters)

An anti-missile system operates after Iran launched drones and missiles towards Israel (Reuters)

Lieutenant General Herzi Halevi, the Israeli Defence Forces’ Chief of Staff, declared that Iran’s attack had “created new opportunities for cooperation in the Middle East.” Similarly, the Institute for National Security Studies, an Israeli think tank, opined that “the regional and international coalition that participated in intercepting launches from Iran toward Israel demonstrates the potential of establishing a regional alliance against Iran.”

Iran has been isolated from the Islamic world since 1979, when Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the anglicised Shah of Iran was forced into exile, ending 2,500 years of monarchy in the Persian Gulf. Once a thriving regional power, after the revolution, Tehran’s relationship with the Arab world soured, resulting in a war against Iraq and proxy conflicts with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Qatar among others.

Exporting the Iranian Revolution

The departure of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi from Iran in January 1979 and the subsequent establishment of the Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini marked a profound ideological change in Iran.

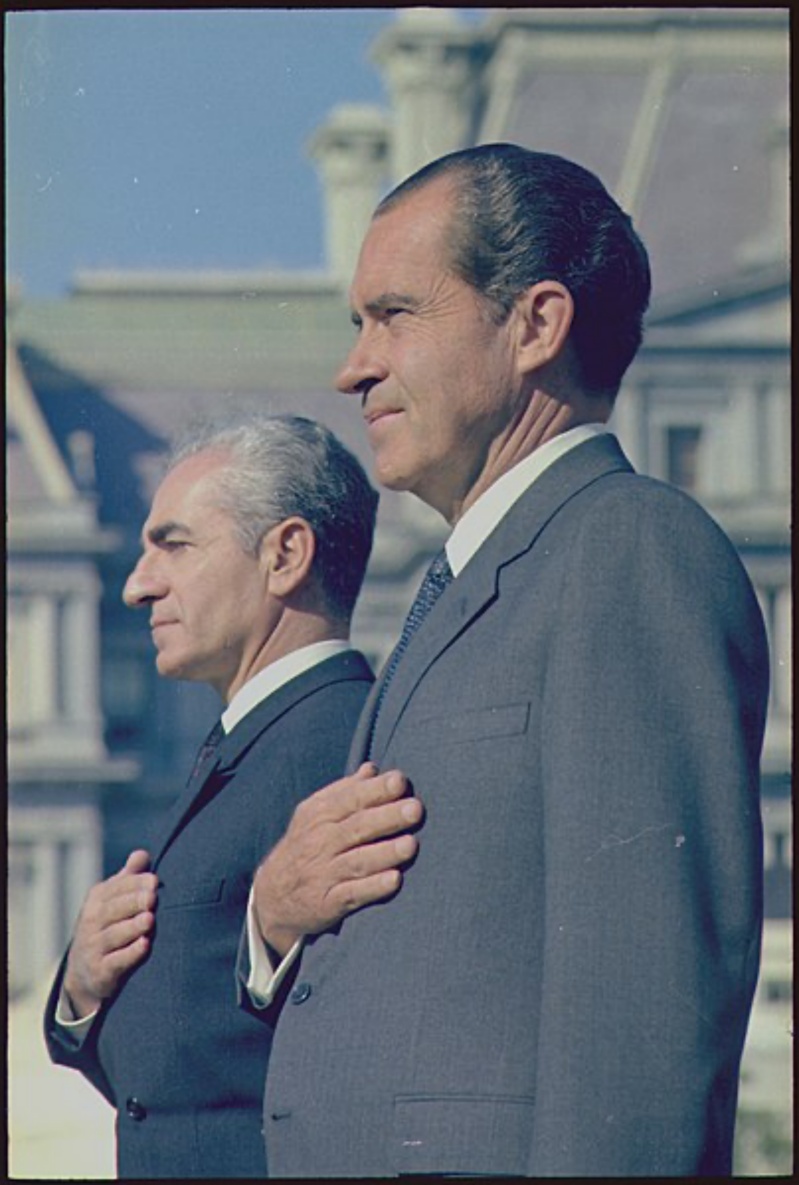

This transformation represented not only a change in governance but a radical re-orientation of the country’s political, social, and international identity, from a secular, pro-Western monarchy to a theocratic, anti-Western regime. During his nearly 40 years in power, Pahlavi had established Iran as the dominant Muslim state in the Middle East, largely due to the support provided by its friends in Washington. The foreign policy of imperial Iran was centred around regional stability, the pursuit of which required financial and military support from America.

The Shah of Iran with US President Richard Nixon (Wikimedia Commons)

The Shah of Iran with US President Richard Nixon (Wikimedia Commons)

When the regime changed, so did Iran’s diplomatic priorities. As Houman Sadri, a professor of international relations at the University of Central Florida argued in an article Trends in the Foreign Policy of Revolutionary Iran (1998), during the revolution, Khomeini and his supporters had painted the Shah as a weak and illegitimate leader. In an attempt to distance themselves from that image, the revolutionary leaders adopted a policy of non-alignment, separating Iran from the “non-Islamic and anti-Iranian” notion of dependency on the West.

While the Iranian Revolution is viewed as an Islamic movement, it’s often forgotten that it was originally not aimed at creating an Islamic theocracy. The movement was spearheaded by a coalition of actors including Islamists loyal to Khomeini, secular intellectuals, communists, and populists. A variety of social groups instigated the revolution but it was the supporters of Khomeini that were willing to go the distance, evidenced by their decision to set fire to Cinema Rex in the southwestern city of Abadan in 1978.

In The Roots and Consequences of Civil Wars and Revolutions (2017), the acclaimed historian Spencer C. Tucker writes of the tragedy: “In Abadan, four Islamic militants bar the door of the Cinema Rex movie theater and then set the building on fire, killing 422 people inside. Khomeini blames the shah and SAVAK (the Iranian secret police), and many Iranians believe the lie. Tens of thousands march in the streets chanting Burn the shah! Soon hundreds of thousands of Iranians are taking part in renewed demonstrations.”

Following the revolution, the Islamist movement under Khomeini took power, establishing what is to date the world’s only clerically-ruled government. In post-revolutionary Iran, as academic Juan Cole writes for the US Institute for Peace, “religion and politics are inseparable.” Shia Islam is not only the religion of the state but also the backbone of law, governance, and foreign policy. Concerning the latter, Iran sought to ‘export the revolution’ much like the French attempted to export liberal principles in 1792 and the Americans exported democratic ideals during the Cold War.

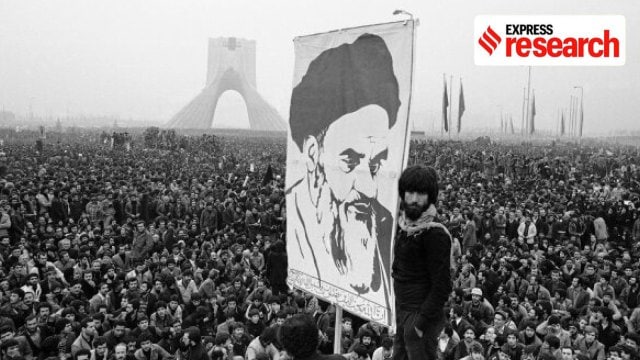

Mass demonstration in Iran during the Revolution (Wikimedia Commons)

Mass demonstration in Iran during the Revolution (Wikimedia Commons)

According to the writings of Khomeini, the Islamic community had been a unified entity since the time of Muhammad, later disintegrating due to internal anti-Islamic behaviour and the influence of colonising powers. The revolution, he argued, would be the glue that would integrate these scattered territories, writing that “until the cry ‘There is no God but God’ resounds over the whole world, there will be a struggle.”

An example of Khomeini’s worldview can be found in his letter to Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev in 1989, where he states that both East and West are ideologically bankrupt because they lack Islamic values. As the late American writer Sandra Mackey notes in The Iranians (1998), “In their view, Iranian foreign policy centers on the export of the revolution, even by subversion and terrorism.”

Iffat S Malik, a fellow at the International Institute of Strategic Studies notes that the export of the revolution was most successful in Lebanon, which, angered by Israel’s invasion, was particularly receptive to the message of the Supreme Leader. However, according to Malik, elsewhere, Khomeini saw little success, prompting his successors to underplay his aspirations of spreading the revolution to other countries. Malik states that “Iran’s harsh rhetoric alienated many of its neighbours in the Middle East, especially the Sunni majority countries, who feared similar uprisings in their own countries.”

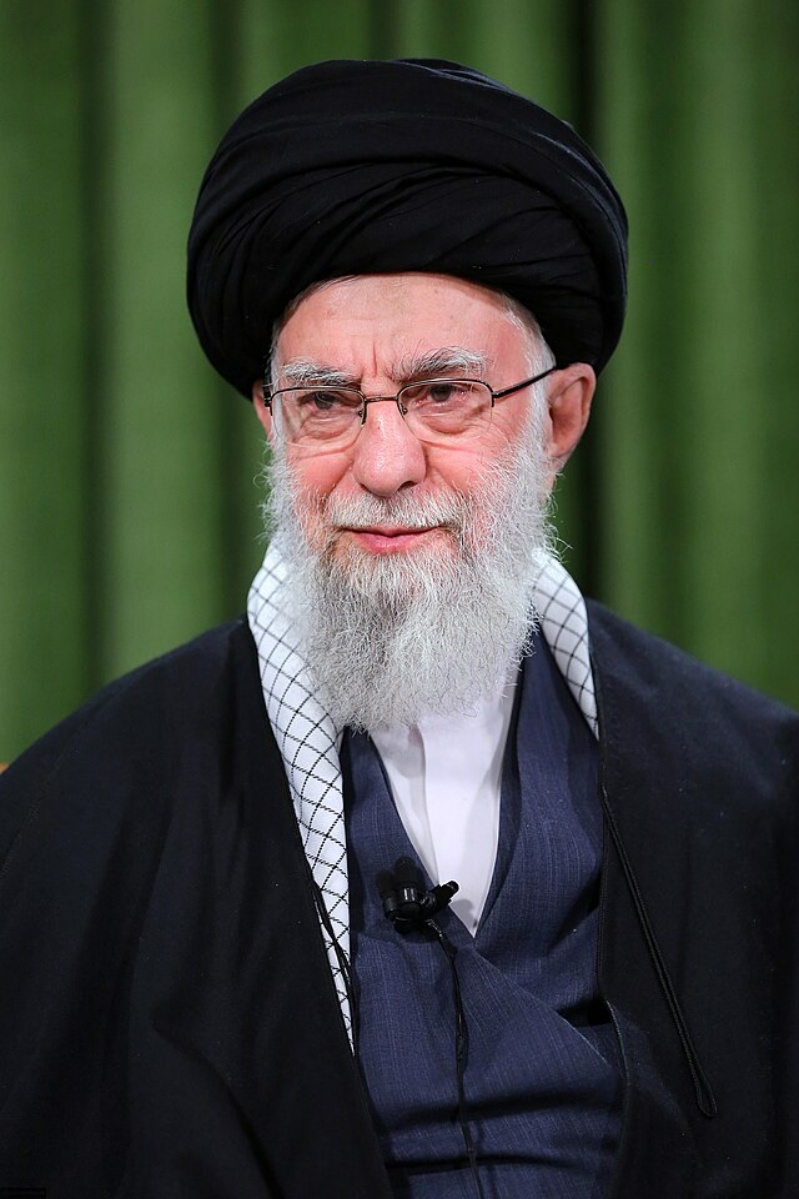

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (Wikimedia Commons)

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (Wikimedia Commons)

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who replaced Khomeini after he died in 1989, even felt the need to clarify, writing that “the export of revolution did not mean that we would rise up and throw our weight and power around and begin wars, forcing people to revolt and carry out revolutions. That was not the Imam’s intention at all.” However, based on Iran’s early stance towards Saudi Arabia and Iraq, observers would not be blamed for thinking otherwise.

Iraq

The first challenge for the nascent Iranian Republic came in the form of Saddam Hussein who also aimed to unite the Arab world, although under a vastly different ideology. While Iran and Iraq are both Shia-majority states, Saddam himself was a Sunni and advocated for a more Arab-centric interpretation of Islam. Preceding the nearly eight-year-long conflict between Iran and Iraq (instigated by the latter), Khomeini depicted Saddam as a godless leader, akin to the recently deposed Shah. He told his supporters, “You are fighting to protect Islam and he (Saddam) is fighting to destroy Islam.”

However, the conflict was far more nuanced, driven by politics as much as ideology.

Iraqi soldiers hold a white flag as they surrender during a ground battle in Kuwait (Reuters)

Iraqi soldiers hold a white flag as they surrender during a ground battle in Kuwait (Reuters)

After the United Kingdom announced its intention to withdraw from the Persian Gulf in the late 1960s, long-standing territorial disputes between Iraq and Iran were rekindled. Facing domestic instability in 1975, Saddam conceded some of his country’s claims in exchange for the cessation of Iranian interference in Iraq. Following the revolution, Iran was weakened by its purported isolationism, and alienated from its biggest ally — the US. Saddam, who considered the 1975 treaty as lopsided, saw the revolution as an opportunity to right a historical wrong, viewing it, according to Sadri, as “a weakness to be exploited.”

In September 1980, the Iraqi army advanced into Iran, initiating a devastating conflict that would last for nearly a decade. Following years of bloodshed and destruction, the two countries agreed upon a ceasefire in 1988 but for Iran, the legacy of the war was not just economic and social, but political as well. From the onset of the revolution, Khomeini and his supporters had maintained a policy of exporting Shia ideals by any means necessary. However, a year before his death, Khomeini accepted the UN Security Council Resolution 598 which called upon both countries to adopt a ceasefire. According to Malik, this “paved the way for better relations between Iran and the Arab world.”

A decade after the revolution, following the war and Khomeini’s passing, Iran’s clerical leaders began to revise their foreign policy, shifting their emphasis on developing Tehran as an economic power instead of a maximalist military actor. During Iran’s so-called ‘Second Republic,’ its first two Presidents, Akbar Rafsanjanī and Mohammad Khatami, adopted a restrained approach towards foreign policy. Rafsanjanī sought to repair Iran’s relationships with the other Gulf states, even providing financial aid to Iraq during the 1991 Persian Gulf War. During Khatami’s presidency, Iran’s foreign policy rejected the Western notion (inspired by author Samuel Huntington) of clashes between civilisations, favouring instead a “dialogue amongst civilisations”.

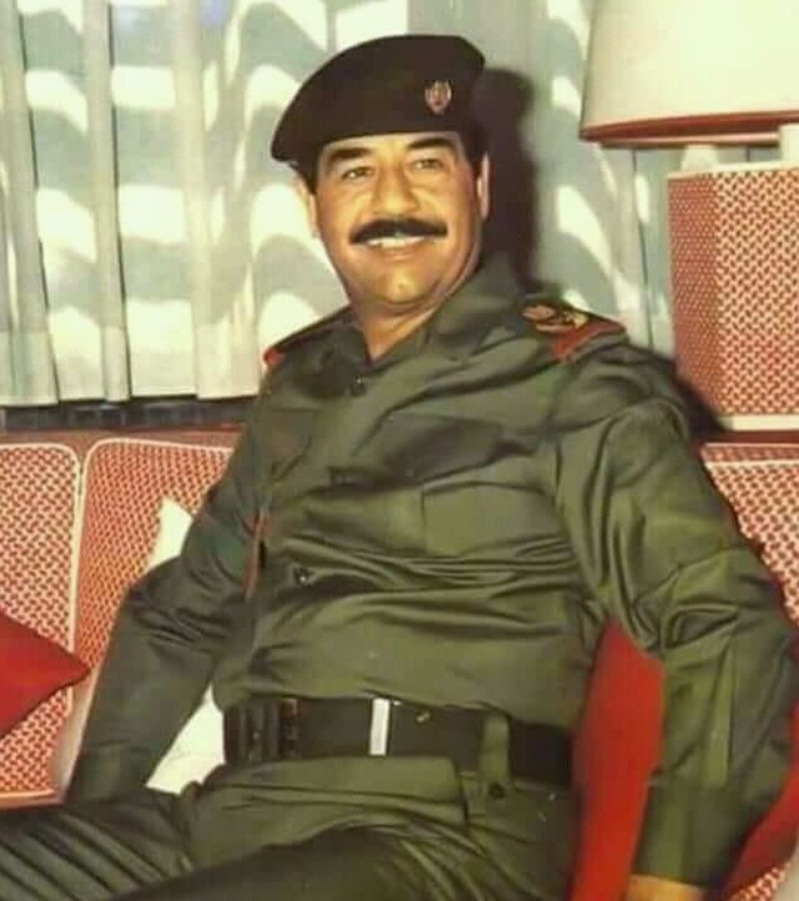

Saddam Hussein in 1980 (Wikimedia Commons)

Saddam Hussein in 1980 (Wikimedia Commons)

Once again, however, Saddam would alter the course of Iranian foreign policy – this time, with his capture and subsequent execution at the hands of the United States. According to Williamson Murray and Kevin M Woods, authors of The Iran–Iraq War: A Military and Strategic History (2014), Iranians saw the collapse of Saddam’s government as a validation of the sacrifices made during the Iran-Iraq war.

Iran did not support the US invasion of Iraq but it did see it as an opportunity to fill a growing power vacuum in the region. Iraq was divided in 2003, and Iran, with whom it shares a 1,600 km border, along with centuries of common history and culture, was more than happy to pick up the pieces. “You simply cannot move Iraq and Iran apart,” former Iraqi president Barham Salih said at a Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) event in 2021, reflecting on their tendency to apportion the destiny of the other.

Iran has been deeply involved in Iraqi politics since 2003. According to a 2022 CFR report, How Much Influence Does Iran Have in Iraq, more than a dozen Iraqi political parties have ties to Iran, and they also fund and train paramilitary groups affiliated with those parties. Tehran has also funded the restoration of thousands of Shia shrines in Iraq and re-appropriated millions of Iraqi refugees who fled the country during Saddam’s reign.

Sunni-Shia

Like Iran holds the de facto mantel for Shia leadership, Saudi Arabia is seen as the vanguard of Sunni Islam. Before the Iranian Revolution, Saudi Arabia and Iran maintained a stable relationship. Both were pro-Western monarchies who shared a similar worldview on matters of regional policy.

Nader Hashemi, director of the Center for Middle East Studies, in a 2019 interview with the magazine FairObserver, states that in the 1960s, “sectarianism was not a factor in the politics of the Middle East” with Iran and Saudi Arabia even aligning on the same side of the Yemeni Civil War. However, according to Hashemi, “All of this changed after 1979 when the Saudis and their allies sought to diminish the power and appeal of the Iranian Revolution by playing the sectarianism card.”

The transformation of Iran into an overtly Shia Republic stoked fears amongst the ruling Sunni elite in Saudi Arabia, who in turn, propagated a brand of Sunni Islam known as Wahhabism to counter Tehran’s influence. Saudi Arabia backed Iraq during the 1980-1988 war with Iran and sponsored militants in Pakistan and Afghanistan who were suppressing Shia movements backed by Iran.

Members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (AFP)

Members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (AFP)

In 1981, six Gulf States including Saudi Arabia, formed the Gulf Cooperation Council to counter Iranian influence. For the next decade, Tehran and Riyadh repeatedly battled for control over Mecca. When a group of Iranians attacked Saudi security forces during the 1987 Hajj pilgrimage, Saudi Arabia severed all ties with Iran. Relations improved slightly in the early 2000s but soured once again when Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard attempted to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the United States.

The Arab Spring further exacerbated tensions and in 2016, Saudi Arabia, along with the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Bahrain, expelled all Iranian diplomats.

Iran’s response against this Gulf coalition has been to back non-state actors, forming a so-called Axis of Resistance consisting of Iran, Syria, and their non-state allies in Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, and Yemen. Since the 1979 revolution, Iran has developed a network of over a dozen proxy paramilitary organisations that operate across six countries. Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and the elite Quds Force are believed to have provided arms, training, and financial backing to Shia groups such as Hezbollah (considered a terrorist organisation by the Arab League), Asaib Ahl al Haq (a militia that launched more than 6000 attacks against US forces on Iraqi soil), Harakat Hezbollah al Nujaba (a Syrian paramilitary organisation that supports Shia leaning Bashar al Assad), and Ansar Allah (popularly known as the Houthis, an opposition group in Yemen).

A child holds a Hezbollah flag during the funeral of Hezbollah member, killed by an Israeli strike in December 2023 (Reuters)

A child holds a Hezbollah flag during the funeral of Hezbollah member, killed by an Israeli strike in December 2023 (Reuters)

In 2020, the US State Department estimated that Iran gave Hezbollah, the largest and most heavily armed non-state actor in the world, approximately USD 700 million in funding annually. “Hezbollah’s budget, everything it eats and drinks, its weapons and rockets, comes from the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah announced at a rally in 2016. Iran also provides millions in funding to Palestinian groups including Hamas and Palestine Islamic Jihad, with Yahya Sinwar, a senior Hamas military leader, telling reporters in 2017 that “Iran is the largest supporter of the Izz ad Din al Qassam Brigades with money and arms.”

The proxy conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia has placed the two on diametrically opposing sides in recent history. However, after Iran promised not to instigate Shias living in Saudi to topple the regime, in March 2023, the two countries announced their intent to resume diplomatic relations. Similarly, the UAE restored diplomatic ties with Iran in 2021, Kuwaiti leaders met with their counterparts in Iran to resolve disputed maritime borders in 2023 and Bahrain (a part of Iran until 1971) is in the process of normalising relations with Tehran. Consequently, Iranian trade with Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE has risen by approximately 10 per cent since 2022.

While Israel hopes of an Arab-Israeli partnership against Iran, given the complex geopolitics of the region, encompassing ideology, territorial disputes, and religion, as Washington Post columnist David Ignatius recently opined, Israel has its allies – America, of course, but also the “Arab states that oppose Iran and its proxies as much as the Israelis do.”

May 23: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05