Abstract

A pastoral counseling approach is proposed in this article. The methodology investigates the relationships between religiosity, spirituality, and existential psychology in order to develop a praxis that supports subjective experiences with a sacred reference while also promoting favorable mental health and quality of life conditions. This methodological framework implies ethical counseling, which involves assisting people with religious subjectivation in coping with their everyday life conflicts to reestablish a sense of continuity in a psychosocial context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Quality of life is a subjective construct made up of multiple contours that emerge in a specific cultural context and characterize the experiences of the subjects (Teoli & Bhardwaj, 2022). Subjective experience is linked to central themes in human existence, and its investigation, like that of any other object, is articulated through dialectical observation of its various manifestations. This means that assessing and analyzing quality of life, from a logical standpoint, necessitates the creation, definition, classification, interpretation, and ordering of the phenomena that manifest themselves in subjective experience in a specific historical and cultural context (Bech, 1995; Clay et al., 2022; Fayers & Machin, 2000; Guelfi, 1992; Hoben et al., 2022; Kaplan & Hays, 2022; Le et al., 2022; Sajid et al., 2008). Regarding the evolution of research interest in quality of life over time, an advanced search for full-text articles on “Quality of Life” in Scopus,Footnote 1 entering the terms (TITLE(life-quality) OR TITLE(quality-of-life) OR ABSTRACT(life-quality) OR ABSTRACT(quality-of-life)) in the query box, returned a total of 448,274 document results for the years 1933 to 2022. The first full-text article found by Scopus was published in 1933 in the journal Social Forces under the title “Research in the Social Problems of Old Age.” In this article, the author argues that there is some regenerative capacity in all age periods so that even when social conditions are most adverse, individual have a chance to triumph due to their own vitality; the author also argues that there is a need to care for quality of life as life approaches its end (Hoyt, 1933). Also, on “Quality of Life,” the Scopus advanced search found 14,217 articles in 2010 and 40,419 articles in 2022. The number of articles followed an exponential longitudinal increase over a 50-year period; the number of published articles grew by 284% between 2010 and 2022.

Mental health, in particular, has been recognized as an important aspect of quality of life (Grinde, 2018; Oliver et al., 2005; Salmanian et al., 2020; Sirgy, 2021). In this sense, due to its breadth in theory and practice, some reflections on the concept of mental health are required to outline its contextualization. First, the term mental refers to psychological processes subjectivated in a cultural context that underpin the various ways people relate to themselves and everything around them. Second, since 1948 the World Health Organization (WHO) has defined health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being rather than merely the absence of disease or infirmity (Whitehead, 1992). Although the WHO definition believes that health is not centered on disease or infirmity, it has been criticized because the “complete state of well-being” is an ideal, utopian concept. Furthermore, in a specific historical and cultural context, health is influenced by social, economic, cultural, ethnic-racial, psychological, and behavioral factors that are known to be social determinants of health; Evans et al., 2001; Gunning-Schepers, 1999). Third, it is difficult to distinguish between what is normal and what is abnormal in mental health (Lilienfeld & Marino, 1999; McNally, 2011; Spitzer, 1999; Stein et al., 2010), so the concept of normalcy receives special attention implied in the adoption of criteria based on philosophical, ideological, and pragmatic options, among others, from the professional or institution in which health care is provided (Dalgalarrondo, 2019). Regarding the evolution of research interest in mental health over time, an advanced search for full-text articles on “Mental Health” in Scopus, entering the terms (TITLE(mental-health) OR ABSTRACT(mental-health)) into the query box, returned a total of 281,051 document results between 1906 and 2022. The first full-text article found by Scopus was published in 1906 in JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association under the title “Mental Health of School Children,” in which the impact of schoolwork on children’s mental development is discussed (Mental health of school children, 1906). Also, on “Mental Health,” a Scopus advanced search found 7,472 articles in 2010 and 34,226 articles in 2022. The number of articles followed an exponential longitudinal increase over a 50-year period, so the number of published articles increased by 458% between 2010 and 2022.

Current research has revealed the impact of religion (religiosity and spirituality) on mental health and, as a consequence, quality of life (Alton, 2020; Danzer, 2018; Kam, 2020). Religion has played an important role in human existence since its inception in societies, being practiced at weddings, periodic religious meetings, baptism or circumcision ceremonies, and other forms of religious integration in daily life (Beyer, 2020; Glass, 2019; Yinger, 1957). The principles of religion create a link between subjective experience and some sacred reference, which, when invoked through devotions and ritual observances, is capable of transmitting protection, providing a “meaning of being,” and influencing personality traits (Olson, 2019; Paloutzian & Park, 2005). From a postmodern perspective, religion reflects a wide range of interpretations, making coming up with a universally valid definition a difficult and authoritative task (Ukuekpeyetan-Agbikim, 2014). Several studies on religion in the specialized literature offer substantive and functional definitions. Substantive definitions address the content and essence of religion, i.e., what religion is: human belief in extraordinary phenomena that cannot be experienced with the sense organs or grasped with the intellect. Functional definitions address religion’s utility or effect on individuals and society, i.e., what religion does (Berger, 1974; Furseth & Repstad, 2006). Regarding the evolution of research interest in religion over time, an advanced search for full-text articles on “Religion (Religiosity and Spirituality)” in Scopus entering the terms (TITLE(religion) OR TITLE(religiosity) OR TITLE(spirituality) OR ABSTRACT(religion) OR ABSTRACT(religiosity) OR ABSTRACT(spirituality)) into the query box returned 146.544 document results in total between 1855 and 2022. The first full-text article found by Scopus was published in 1885 in the journal Notes and Queries under the title “Different Ideas of a Religion among Christians and Pagans. Also, on “Religion (Religiosity and Spirituality),” the Scopus advanced search found 5,459 articles in 2010 and 8.523 articles in 2022. The number of articles followed an exponential longitudinal increase over a 50-year period; the number of published articles increased by 156% between 2010 and 2022.

Because quality of life, mental health, and religion (religiosity and spirituality) are all interrelated in the establishment of subjective experiences, there is a growing interest in integrating quality of life, mental health, and religion (religiosity and spirituality) for effective studies. Figure 1 depicts a summary of the number of articles identified in Scopus corresponding to the relation between religion (religiosity and spirituality) and quality of life, entering the following terms in the query box, (TITLE(((quality-of-life) OR (life-quality)) AND (religion OR religiosity OR spirituality)) OR ABSTRACT(((quality-of-life) OR (life-quality)) AND (religion OR religiosity OR spirituality))), as well as the relation between religion (religiosity and spirituality) and mental health, entering the following terms in the query box, (TITLE((mental-health) AND (religion OR religiosity OR spirituality)) OR ABSTRACT((mental-health) AND (religion OR religiosity OR spirituality))). The Scopus advanced search returned 2,158 document results in total on RELIGION (RELIGIOSITY AND SPIRITUALITY) x QUALITY OF LIFE between 1972 and 2022. The first full-text article found by Scopus was published in 1972 in Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science under the title “Churches at the Transition Between Growth and World Equilibrium,” which was originally presented at the annual meeting of the program board of the Division of Overseas Ministries of the National Council of Churches. The author of this article suggests that laws, policies, and religions can be redirected to achieve a smooth transition to world balance. Even in the choice of balance, alternatives emerge. The author argues that the decision to maximize current quality of life condemns future generations to suffer at the expense of the advantages enjoyed by their forebearers (Forrester, 1972). Also, on RELIGION (RELIGIOSITY AND SPIRITUALITY) x QUALITY OF LIFE, the Scopus advanced search found 85 articles in 2010 and 177 articles in 2022. The increase in published articles was 208% from 2010 to 2022. Over a 50-year period, the growth in the number of articles on RELIGION (RELIGIOSITY AND SPIRITUALITY) x QUALITY OF LIFE followed an exponential longitudinal curve. The Scopus advanced search returned 3,696 document results in total on RELIGION (RELIGIOSITY AND SPIRITUALITY) x MENTAL HEALTH between 1942 and 2022. The first full-text article found by Scopus was published in 1942 in Journal of Heredity under the title “Education for Family Life” and deals with the importance of education for family life, from early childhood education to adulthood, through all phases of education, social work, law, medicine, and religion that affect family life in the local, state, and national communities. According to the author, certain family functions, such as physical reproduction of the race, physical care and training of the young child, and provision of the fundamental sources of mental health and happiness become increasingly important in this context (Taylor, 1942). Also, on RELIGION (RELIGIOSITY AND SPIRITUALITY) x MENTAL HEALTH, the Scopus advanced search found 116 articles in 2010 and 427 articles in 2022. The increase in published articles was 368% from 2010 to 2022. Over a 50-year period, the growth in the number of articles on RELIGION (RELIGIOSITY AND SPIRITUALITY) x MENTAL HEALTH followed an exponential longitudinal curve.

The aforementioned studies and research support the scenario in which people seek counseling and spiritual guidance to be encouraged to make positive decisions in dealing with their everyday existential problems. This has motivated religious leaders to emphasize the significance of understanding human nature from an ontological perspective to provide counseling and spiritual guidance. According to Scottish theologian John Oman (1860–1939), religious leaders must first understand human nature before they can be agents of transformation (Bevans, 2007; Oman, 1919, 1931, 1941). Leslie Dixon Weatherhead (1893–1976), an English theologian, stated to a group of religious leaders in New York City that counseling and spiritual guidance support a “personality reconstruction” function and that comprehension of human nature is thus required (Weatherhead, 1999). Therefore, this article considers developing a counseling approach based on the interrelationship between religion, mental health, and quality of life, taking into account the pillars of religiosity and spirituality as well as subjective experiences related to existential questions about human nature.

Methodology

Human nature has been studied for centuries because it is inextricably linked to subjectivation and subjective experience (Dupre, 2001; Fuentes, 2017; Fuentes & Visala, 2016; Hinde, 1976; Horodecka, 2014). Subjectivation is the process by which certain forms of relationship with oneself and the world emerge in a specific socio-historical context, culminating in a distinct subjective experience that defines ways of thinking, acting, and feeling (Guénoun & Attigui, 2021; Levitt et al., 2022). As a result, the process of counseling in a religious context requires the intellectual ability to properly integrate perspectives from religious studies and human sciences to analyze human nature.

The religious studies perspective on human nature

The word “religion” is derived from the Latin word ligare, which means “to join” or “to link,” and is traditionally understood to refer to the union of human and divine (Jones, 2005; Nye, 2008). Religious studies is a scientific field with many courses available at universities all over the world. Religion studies aims to investigate religious phenomena in their entirety and includes subcategories such as anthropology of religion (Bowie, 2005), economics of religion (Carvalho et al., 2019), geography of religion (Stump, 2008), psychology of religion (Paloutzian & Park, 2014), sociology of religion (Weber et al., 1993), and phenomenology of religion (Cox, 2006). To understand the religious studies perspective on human nature, definitions of “religion” must be offered. According to Ninian Smart (1998), a Scottish scholar of religion, religion is defined by seven dimensions (the seven categories that characterize religious studies): (1) practical and ritual dimension, (2) experiential and emotional dimension, (3) narrative and mythic dimension, (4) doctrinal and philosophical dimension, (5) ethical and legal dimension, (6) social and institutional dimension, and (7) material dimension.

The practical and ritual dimension of religion encompasses all aspects of religious performance, including both formal ritual (activities governed by rules that govern performance and motivation) and more informal, everyday practices (activities with a religious motivation or character). The experiential and emotional dimension is concerned with subjective reactions to religious experiences. Religion’s storytelling aspect is described in the narrative and mythic dimension. The doctrinal and philosophical dimension refers to how religions formalize ideas about the world and construct logical meaning systems. The ethical and legal dimensions describe how religion tends to provide guidance on how to live one’s life, generally in order to achieve happiness in this or the next life. The social and institutional dimension represents how religious adherents tend to form organized bodies that behave collectively when they act together. The material dimension describes how religions lead to the creation of material artifacts, provides evidence for historians and archaeologists, and enriches the lives of modern religious adherents as their beliefs and traditions come to life in the world through physical media. Religion, according to (Koenig et al., 2012), is an organized system of practices and beliefs, including rites and symbols, shared by members of the same religious group with the goal of bringing people closer to the transcendent.

Given these definitions, it is possible to conclude that religion is a dynamic process of beliefs and practices, initially aimed at the discovery of meaning, that motivates people to nurture and maintain their relationships through religious practices and, in essence, influences the way people relate to themselves and the world around them. These considerations support the notion that religion is a subjectivation mechanism responsible for producing subjective experiences in human nature, which are expressed through religiosity and spirituality (Cunha et al., 2020; Obregon et al., 2022; Sheldrake, 2007; Tanyi, 2002; Whitehouse, 2004; Zareba et al., 2022).

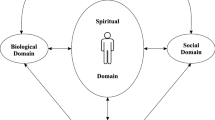

Subjectivation corresponds to how human nature relates to itself and the world in a specific historical context. Each historical formation in turn generates a subjective experience. Subjectivity refers to the creation of a specific way of being in human nature that is dynamic rather than static. Human nature is constantly reinventing itself in terms of subjective experience due to the relationship between the process of subjectivation and the production of subjectivity (Bergen & Verbeek, 2021; Cascais, 2023; Röthl, 2021). The proposal of a conceptual model that represents the process of subjectivation from religion on human nature, demonstrating its effects on religious subjective experience in terms of religiosity and spirituality, is presented in Fig. 2. Despite their different definitions, religiosity and spirituality are intertwined in this model. Religiosity refers to actions based on rituals, traditions, and dogmas that seek to connect human nature with the sacred reference. Spirituality refers to transcendent manifestation combined with the emotions, feelings, and thoughts associated with the connection of human nature with the sacred reference. It is possible to see a bidirectional relationship between religiosity and spirituality. This means that in religious life, the factors involved in religiosity have an impact on spirituality and the factors involved in spirituality have an impact on religiosity.

In a specific social and historical context, the dynamic interrelationship between religiosity and spirituality ensures the creation of experiential conditions that make up meaning for religious life, developing a critical attitude toward various ways of understanding in general and in relation to the individual. In its relationship with religion, human nature is thus seen in its entirety, in broad strokes, and as in constant flux. Human nature creates and derives meaning from everything it confronts, establishing a permanent critical attitude in its historical being and the values that guide its actions. Human nature does not react mechanically to what happens to it but instead seeks the best means of anticipating how events will unfold. In the light of religion, human nature evolves a set of meanings based on subjective religious experience expressed through religiosity and spirituality. The subjective experience of human nature explains why different people have different expressions of religiosity and spirituality even though they belong to the same religion. Religious subjectivation provides human nature with a new perspective on reality. Because human motivations are shaped by perceptions of reality rather than by reality itself, subjective perceptions shape behavior and personality. This means that religious subjectivation causes human nature to perceive reality through the lens of its religious worldview, resulting in a religious way of life characterized by internal and external subjective experiences that serve as important mediators of human interactions and authentic experiences in the search for meaning in life.

The human sciences perspective on human nature

Human sciences seeks to broaden the understanding of human nature through a multidisciplinary approach that includes sociology, psychology, anthropology, political science, philosophy, literary criticism, critical theory, art history, linguistics, and the law by engaging the histories of these disciplines and their interactions (Henderson, 1993; Hoyrup, 2000). Among the multidisciplinary fields of human sciences, psychology investigates subjectivity in order to understand the totality of human nature in all its manifestations (Feist, 2008; Hergenhahn & Henley, 2013), and, as a consequence, it is an effective tool for analyzing, assessing, and intervening in mental health (Kang et al., 2020; Owen, 2015; Piotrowski, 2010) as well as quality of life (Efklides & Moraitou, 2013; Sirgy, 2002; Zis et al., 2019). For this, psychology has several schools of thought for analyzing the construction and development mechanisms of subjectivity in human nature, such as the psychodynamic approach, cognitive behavioral approach, humanistic approach, and existential approach (Bock et al., 2008; Larsen & Bus, 2008; Maltby et al., 2010).

The psychodynamic approach is a school of thought in psychology that includes various theories whose perspectives on human nature consider emotions (aggression, anger, sadness, etc.), past experiences, interpersonal relationships, desires, dreams, fantasies, and how the unconscious mind influences human nature’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. This approach is greatly influenced by Sigmund Freud’s (1856–1939) psychoanalytic theory, Alfred Adler’s (1870–1937) individual psychology, Carl Gustav Jung’s (1875–1961) analytical psychology, Melanie Klein’s (1882–1960) object relations theory, Karen Horney’s (1885–1952) psychoanalytic social theory, Eric Fromm’s (1900–1980) humanistic psychoanalysis, Erik Erikson’s (1902–1994) post-Freudian theory, and others’ theories (Bienenfeld, 2006; Colarusso & Nemiroff, 1981). According to psychodynamic theory, forces both beneath and above the conscious surface shape human nature over time. It looks beyond the conscious surface to answer questions about how human nature came to be the way it is and the subterranean forces that shaped human nature, while also considering this to be important for understanding human nature’s past, present, and future. The approach takes into account hereditary and environmental influences that impacted human nature’s early experiences throughout its life cycle in order to develop hypotheses about the impact and development of unconscious content associated with the way human nature interacts with itself and the world around it. Its formulation and practical structure, in general, consists of an initial description of problems and patterns relevant to subjective difficulties, followed by an examination (review) of previous subjective experiences from the developmental history, and finally the organization of ideas linking past experiences to current subjective difficulties (problems and patterns) through the use of different organizing ideas about development, with the goal of assisting humans in learning about themselves and developing in order to live more meaningful and free lives. It is important to emphasize that psychodynamic formulations do not provide definitive explanations but rather raise hypotheses that can change over time (Busch, 2021; Cabaniss et al., 2013; Fonagy, 2015; Shedler, 2010).

The cognitive behavioral approach is a school of thought in psychology that was founded around 1960 by the American neurologist and psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck (1921–2021), whose perspective on human nature is based on the principles that cognitions influence emotions and behavior and that behavior can influence thoughts and emotions (Becker, 1986; Rasmussen, 2005; Wright et al., 2017). Cognitive processing is central to this approach because human nature evaluates the relevance of events both internally and in their surroundings, and cognitions are frequently associated with emotional reactions. The cognitive behavioral formulation is based on obtaining the necessary information to understand the conditions of human nature as influenced by multiple domains such as diagnosis and symptoms, cognitive and behavioral elements, situational and interpersonal issues, sociocultural basis, childhood and developmental experiences, biological/genetic/medical factors, strengths and qualities, automatic patterns of thoughts/emotions/behaviors, and underlying cognitive schemas. This information is then used to assess the suitability of human nature for the application of this approach, taking into account subjective aspects such as the chronicity and complexity of the problem, responsibility to change, access to automatic thoughts and emotion identification, and problem-oriented focus. The cognitive behavioral approach’s main resources in this regard are structuring methods (setting goals and agenda, evaluating and checking symptoms, feedback, prescribing homework) and psychoeducation, with the proposition of assisting in the resolution of subjective issues (Livet & McCluskey, 2019; McMullin & Giles, 1981; Nezu et al., 2004; Strouse & Bursch, 2018).

The humanistic approach is a psychological school of thought that emerged in the early 1950s and was strongly influenced by Jacob Levy Moreno’s (1889–1974) psychodrama, Friedrich Salomon Perls’s (1893–1970) gestalt therapy, Carl Rogers (1902–1987) person-centered theory, and Abraham H. Maslow’s (1908–1970) holistic dynamic theory, among others (Cain et al., 2015; Schneider et al., 2015). In general, the humanistic approach emphasizes the study of human nature as a whole, as well as the uniqueness of human nature. According to this perspective, human nature is at the center of all efforts; it is viewed as an end in itself and of supreme value, innately driven to meet its full potential (self-actualization). In practice, it takes into account the human mindset, the fact that human nature employs inherently subjective resources in order to be conscious, intentional, self-directed, a bearer of potential will and possibilities, and a creator of conditions for growth. This approach is concerned with empathetic entering human nature’s worldview to provide an experiential environment appropriate for valid interpersonal relationships and emotional expressions, comprehending human nature as a meaning-creating and symbolizing agent of subjective experiences and as providing new modes of subjectivation potentially favorable for awareness. The primary goal is to meet human needs in the context of subjective experiences that present barriers to self-actualization arising from unique life circumstances. This is helpful in overcoming these barriers by creating awareness, assessing what is impeding self-actualization, and providing reflections as advice to empower human nature to a place of autonomy where free will can be acceptable for taking responsibility in life, determining the route to self for maximizing self-actualization, and discovering potentialities for acting based on a self-knowledge process (Angus et al., 2015; Giglio, 2022; Hazarika & Choudhury, 2019; Hwang, 2022).

The existential approach is a school of thought in psychology that has philosophical roots dating back to the 1800s. It addresses important issues about human existence such as finding meaning in life, dealing with identity crises, confronting aloneness, and managing anxieties. Specifically, it is founded on the philosophical theories of Soren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), who is recognized as the father of the existential approach, and Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844–1900). Rollo May (1909–1994) was an American psychologist who became a leading proponent of the existential movement (Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015; Spinelli, 2014). The existential perspective, in contrast to the humanistic point of view, argues that human nature is constantly projecting itself outside of itself to find meaning and to constitute its own existence. Furthermore, human nature seeks a meaning for its existence, is free and responsible for its choices and actions, and expresses itself and its life consciously (Jacobsen, 2007). In this sense, this approach seeks to comprehend human nature’s worldview while creating environments in which human nature confronts its inner conflicts, attempts to connect with and recognize them, and increases its self-awareness. It is concerned with providing a relational encounter, being present in the here-and-now, and encouraging responsibility and independence. Its practice is summarized as follows: identifying how the presenting problems are related to existential assumptions and beliefs (death anxiety, freedom and responsibility, isolation and relationship, meaninglessness, meaning, purpose, existential anxiety and guilt, existential angst, purpose of neuroses, and so on), stimulating the examination and redefinition of attitudes toward these existential assumptions and beliefs, and stimulating specific action to lead a more fulfilling, meaningful, and self-actualized life (Feizi et al., 2019; Lewis, 2014; Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2021; Vos et al., 2015; Ziaee et al., 2022).

Martin Mordechai Buber (1878–1965), Karl Theodor Jaspers (1883–1969), Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), Nicola Abbagnano (1901–1990), Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (1905–1980), Viktor Emil Frankl (1905–1997), and Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908–1961), to name a few, all had a significant influence on existential studies, leading to the well-known existential phenomenological approach, which arose from a reorientation of phenomenological inquiry toward the meaning of existence, investigating the inherent potentials of human nature as “being-in-the-world” (Flynn, 2006; Moore, 1967; Reynolds, 2006; Schrag, 2012). According to the etymological basis of the Latin verb exsistere, which means “become, emerge, go out,” existential phenomenology focuses on existence as preceding the essence (the Being does not have existence but is its own existence). Its object is “existence,” which refers to what and how human nature is in relation to the world, accepting both freedom and projections, and which lies in its subjective ability to give meaning to its own existence (Lee & Mandelbaum, 1967; Solomon, 2005; Zieske, 2020). Existential phenomenology seeks to understand and clarify human existence through four major themes, all of which are consistent with the current and future promotion of psychological well-being (Ahmed, 2019; Judaken & Bernasconi, 2012; Schulenberg, 2016): (a) the inevitability of a universe devoid of clear or easily fixed meaning, as well as an eventual nothingness or death, (b) the inherent freedom to choose attitudes and actions in the face of potentially meaningless situations, (c) the restrictions or limits that situations impose on freedom, and (d) the impossibility of avoiding responsibility for any choice.

The religious counseling approach

This article discusses a religious counseling approach that is based on the proposition of the religious-existential conceptual model depicted in Fig. 3. According to this conceptual model, human nature manifests as a fundamental unit, which is expressed by the German word Dasein, which literally means existing in the world and, in general, is written as “Being-in-the-world,” implying that human nature exists in a relationship of unification with the world. In this way, human nature simultaneously experiences the Umwelt mode of Being-in-the-world when relating to the world around it (things/objects), the Mitwelt mode of Being-in-the-world when relating to the world of people, and the Eigenwelt mode of Being-in-the-world when relating to its self. Understanding not-Being (or nothingness) is necessary for awareness of Being-in-the-world (existence) because death is the only absolute fact in life that can occur at any time. The existence of human nature precedes its essence, which is the driving force that propels human nature to constantly redefine itself through the choices it makes. Human nature, through its existence, reveals itself by itself in its search for truth through an active and authentic posture of its existential subjectivity, leading to an experience with some meaning for life with an awareness of its freedom, responsibility, and will. Existential subjectivity, in turn, is expressed by various manners in which human nature is being itself, from its existential worldview, through the fundamental pillars of mental health and quality of life. Religious subjectivation, in this existential framework, is a dynamic and historical process arising from the relationship between religion in the Umwelt and the self in the Eigenwelt. In this way, human nature reveals itself by itself in its search for truth through an active and authentic posture from its religious subjectivity, leading to an experience with some meaning for life and an awareness of its freedom, responsibility, and will. Religious subjectivity, in turn, is expressed in the various manners in which human nature is being itself, from its religious worldview, through the fundamental pillars of religiosity, spirituality and faith. Thus, despite having distinct experiential domains, existential subjectivity and religious subjectivity may mutually influence one another in the search for meaning in life.

Therapeutic procedure

Given that there are factors in the authenticity of human nature that arise solely from existential subjectivity as well as factors that arise solely from religious subjectivity, it is necessary and sufficient to consider both subjectivities in counseling. In other words, the demands that arise in the context of counseling use both religious and existential content, and, as a consequence, counselors must be equipped with the intellectual skills to provide valid guidelines that meet both religious subjectivity (religiosity, spirituality, and faith) and existential subjectivity (mental health and quality of life) while avoiding any conflicts of interest. This implies two important considerations for practical counseling. The first application is for professionals such as psychologists, psychiatrists, mental health technicians, marriage and family therapists, and others whose counseling methodology emphasizes the existential subjectivity of human nature while also taking into account the pillars of religiosity, faith, and spirituality associated with religious subjectivity. The second application is for religious leaders such as pastors, priests, bishops, and others whose counseling methodology emphasizes the religious subjectivity of human nature while also taking into account the pillars of mental health and quality of life associated with existential subjectivity.

The methodology developed in this article is centered on religious counseling and thus fits into the context of the aforementioned second consideration for practical counseling, as illustrated by the hatched area in Fig. 4, that is, counseling from a religious worldview that incorporates existential subjectivity into its guidelines. In accordance with this methodological viewpoint, this article employs an alternative theoretical model for comprehending the term pastoral counseling.Footnote 2 The word “pastoral” refers to culture, environments, and people in the context of a religious worldview. The word “counseling” refers to strategies, methods, and tools that can be used in a dialogic relationship, in the context of a scientific meaning derived from existential psychology. Therefore, pastoral counseling is viewed as a dialogical relationship between two people: the counselors (pastors, priests, bishops, and other congregational religious leaders) and the counselees (people with religious or secular worldviews). In this theoretical model, the counselors establish a dialogic relationship with the counselees, creating a learning environment in which the counselees are assisted to become aware of their possibilities/prospects related to existential subjectivity as well as their potentials/characteristics related to religious subjectivity in order to resolve their conflicts in a way that is satisfactory and beneficial for their quality of life, religiosity, faith, spirituality, and mental health.

Procedure for religious subjectivation

Human nature’s religious subjectivity establishes the pillars of religiosity, faith, and spirituality as the foundation for enacting religious postures as expressions of its existence, which involves a human relationship with a sacred reference in its life path. Religious cosmology, religious rules of conduct, and religious reward and punishment schemes are all part of this. It also includes human nature’s ability to transcend itself, to constantly relate with something or someone outside of itself, to go beyond the limits of the sensible world, and to connect to sacred references that are located in another order that is not subject to the reality of a mortal body, such as gods, spirits, cosmic energies, and metaphysical manifestations. Knowing the phenomenon of religious experience, that is, a conception that characterizes the various forms of religious experience constitution performed by human nature as Being-in-the-world, serves as a foundation for effectively delineating guidelines in a counseling therapeutic procedure while carefully taking religious subjectivity into account. In other words, religious counseling is a procedure of subjectivating human nature in the pillars of religiosity, spirituality, and faith, as well as of clarifying beneficial religious ways of living. The status of the relationship between the human and the sacred reference is the central goal, and serving as a means of developing this human-sacred relationship is certainly within the scope of the religious counseling therapeutic procedure.

As a means of expressing existence, religious subjectivity entails the creation of an authentic religious experience that demonstrates a distinguishable meaning of life. This phenomenon of religious experience involves beliefs, attitudes, values, behavior, and experiences, all of which must be considered to establish boundaries or limits within the religious system’s normative framework. Religiosity entails gaining direct knowledge of ultimate reality or experiencing religious emotions, as well as maintaining certain beliefs, religious practices, information, and knowledge about the fundamental principles of faith and sacred scriptures, i.e., all the types of actions that must be maintained as a result of religion. Spirituality entails an experience-based belief in a transcendent dimension of life, a sense of calling and mission, a belief that all life is sacred, a belief that material things do not satisfy spiritual needs, a belief that life is full of spiritual benefits and experiences, a belief in a higher level of reality, a sense of connection to a sacred reference, and, as a consequence, personal change in relation to social involvement. Faith is a component of religious subjectivity that arises from the process of subjectivation of religion in the world of the self (Eigenwel), which gives motivational meaning to the modes of expression of religiosity and spirituality. As a result, investigation, continuous assessment, boundary determination, and encouragement must all be part of religious counseling procedures to develop therapeutically successful care that prioritizes attitudes, beliefs, and values associated with religiosity, spirituality, and/or faith in human nature.

Procedure for existential subjectivation

According to the conceptual model depicted in Fig. 3, human nature’s modes of Being-in-the-world reflect religious and existential subjectivities, which, while intrinsically linked, contribute to an existential worldview that leads to an authentic experience of meaning for life. Mental health and quality of life are two important human nature constructs that are inextricably linked to the psychosocial expressiveness of existential subjectivity. In this sense, it is justifiable for religious counseling to incorporate into its therapeutic procedure the necessary conditions for human nature’s psychosocial well-being. It is possible to aspire that human nature will improve its mental health and quality of life by grasping its existential reality and immediate experience, beginning with the assumption of its active and conscious posture of freedom, responsibility, and will. According to Rollo May’s concepts, existential psychology focuses on human nature’s attempt to acquire knowledge through life’s experiences and grow to become a more complete version of itself in its existence. Human nature experiences mental health and quality of life when it realizes that its existence, or some identified value associated with its existence, is not threatened or destroyed. The awareness and confrontation of existential reality allows for the attainment of freedom, which leads to a sense of purpose and meaning in life.

It is beneficial to have a clear understanding of the goals or destination prior to actually engaging in a variety of productive and constructive behaviors. A focus on relationships with the world around (Umwelt), the world of people (Mitwelt), and, most importantly, the world of the self (Eigenwelt) is beneficial to the development of a sense of self-worth and increased awareness, both of which reflect positively on communication interactions that dynamically involve the ability to know others and share the self. When human nature’s awareness of existential reality expands, a better position for making decisions emerges, leading to a greater degree of both freedom and responsibility. This indicates that discovering inner possibilities of human nature, which arise from a greater awareness of the individual’s freedom and responsibility, allows progress toward creating an authentic experience that leads to a sense of purpose in life. Opening to new possibilities occurs when the situation is accepted and learning is made possible. Emotions must be recognized and comprehended in this context. Every human being’s life includes freedom, responsibility, and existential experiences, and it is from these that growth and a more authentic Being-in-the-world are possible.

The preceding assertions concern the primary aspects of religious and existential subjectivity that influence the formation of an authentic human nature experience oriented toward a sense of purpose in life. Based on this perspective, a detailed outline of a practical procedure for religious counseling is illustrated in Table 1, laying the groundwork for a collection of intellectual competencies and abilities that address spirituality, religiosity, and the existential subjective experience. The flowchart in Fig. 5 depicts the therapeutic procedure to be used in religious counseling. It is important to note that the methodology used in the therapeutic procedure of religious counseling allows for both the counselor and the counselee to grow personally. While the counselee exposes their problems, difficulties, and conflicts, the counselor seeks to clarify the contents related to religious and existential subjectivity presented by the counselee rather than solve the problem. As a result, the counselee gains enough self-awareness to develop action plans for adapting to new existential roles and situations in light of sacred principles as well as for dealing with existential issues positively through religious thoughts and actions. If the counselee does not evolve in the psychosocial context, the counselor must identify the factors limiting this evolution, if possible refer to the client to a psychosocial specialist, and supplement the care of the psychosocial specialist by updating religious support.

Ethical implications

This section discusses the ethical attitude that can be used in religious counseling, which should serve as a backdrop for the therapeutic procedure presented in the previous section. As a starting point, a brief description of the act of counseling is provided. Counseling, according to Carl Rogers’s ideas, is a method of assisting counselees to assist themselves to gain emotional freedom in relation to their problems and, as a result, to think more clearly about themselves and the situation, to see themselves and their reactions more clearly, and to accept their attitudes more fully (Rogers, 1995; Rogers & Yalom, 1995; Vincent, 2016). Based on this understanding, the counselees will be able to address their life problems more adequately, independently, and responsibly than before, experiencing psychological growth and discovering for themselves a path of adjustment to reality and life’s demands. Rogers’s person-centered approach involves certain ethical guidelines that can be viewed as required for an effective therapeutic religious counseling procedure. According to this viewpoint, the ethical attitude involved in religious counseling manifests itself in terms of conditions, procedure, and outcomes, such that interpersonal contact with a counselor who possesses the quality of congruence and provides an atmosphere of unconditional acceptance (positive regard) and accurate empathetic understanding promotes the counselees’ psychological growth. In other words, once the religious counselors’ conditions of congruence, unconditional positive regard, and empathetic listening are present in a communicative interaction with the counselees, the therapeutic procedure of religious counseling will have a positive effect on the counselees, and the results of religious counseling can be prognostic. The more the counselees perceive congruence, unconditional positive regard, and empathetic listening from the religious counselor, the more successful the therapeutic procedure of religious counseling will be.

Congruence is the first necessary and sufficient quality for a religious counselors’ ethical attitude to promote experiential conditions favorable to the counselees’ state of change. Congruence implies the act of being genuine, total, and integrated, of being who one truly is. The counselees will be able to become aware of their organismic experiences, as well as be able and willing to openly express their feelings, under the condition of the religious counselors’ congruence. The ability of the counselees to become aware of their own feelings experienced indicates that they do not deny or distort their feelings but instead allow them to flow freely into consciousness and thus express them freely. Congruent religious counselors are not passive or indifferent. They are able to combine their feelings with awareness and with honest expression.

The unconditional positive consideration is the second necessary and sufficient quality for the religious counselors’ ethical attitude. This quality causes the religious counselors to have a cordial, positive, and accepting attitude toward what the counselees are, free of possessiveness, evaluations, or reservations and stemming from a genuine interest in the counselees’ ontological humanity so that the counselees are autonomous and independent of the religious counselors’ evaluations. This allows the counselees to be themselves and make the best decisions for themselves. The religious counselors accept the counselees without any restrictions or reservations because external evaluation, whether positive or negative, causes the counselees to defend themselves and impedes psychological growth. The term consideration refers to a genuine relationship in which the religious counselors value the counselees; the term positive denotes that the relationship is oriented toward feelings of warmth and attention; and the term unconditional denotes that positive regard is not dependent on the counselees’ specific behaviors and does not need to be constantly earned.

Empathetic listening is the third necessary and sufficient quality for the psychological growth of counselees in religious counseling. In this case, religious counselors comprehend and communicate the counselees’ feelings so that the counselees know that the religious counselors have entered their world of feelings without bias, projection, or evaluation. Empathetic listening is an ethical implication that, through authenticity and attention, facilitates personal growth in the counselees so that the counselees, once they are insightfully understood, genuinely come into contact with a broader range of experiences in understanding themselves and directing their behavior. Empathy is effective because it allows the counselees to listen to themselves and thus become their own counselors. The religious counselors react emotionally and cognitively to the counselees’ feelings without taking ownership of the counselees’ feelings, imparting to the counselees an understanding of what it means to be the counselees at that specific moment.

Final remarks

The assertions presented in this article may be useful to religious/spiritual caregivers (pastoral counselors) who are interested in advancing psychotherapy and counseling techniques. This article presented a counseling approach based on existential psychology and reflections on its usefulness for the formation of counselors as well as the guaranteeing of a religious “meaning of being” to counselees. Counselors can achieve the best efficiency in counseling if they take into account the ontological specificity of the counselees. This understanding is established through their perception of how the counselees show themselves, in the moment of counseling, without any kind of judgment, prejudice, or attribution of value. One advantage of this methodology is that it reduces the impact of negative life experiences. Another is that religion can be a positive force in achieving actualization. Future work on the analysis and application of the proposed approach for group counseling is of particular interest.

Notes

Scopus is a peer-reviewed literature abstract and citation database that includes scientific journals, books, and conference proceedings. It provides a comprehensive overview of global research output in the fields of science, technology, medicine, social sciences, and the arts and humanities: https://www.scopus.com/.

It is known that the term pastoral counseling can be understood in multiple ways. In his book Living Stories: Pastoral Counseling in Congregational Context, Capps (1998) adopts the perspective that ministers in the congregational context who counsel are, in fact, doing pastoral counseling, though he also recognizes that the term has been used to refer to “professional counselors.” Capps also proposes a paradigmatic revolution in pastoral counseling that includes its return as a vital component of parish ministry (Capps, 1998). In the edited volume Understanding Pastoral Counseling, the authors reflect on themes of pastoral counseling as a distinct way of being in the world, understanding client concerns and experiences and intervening to promote the health and growth of clients (Maynard & Snodgrass, 2015).

References

Ahmed, S. (2019). (Un)exceptional trauma, existential insecurity, and anxieties of modern subjecthood: A phenomenological analysis of arbitrary sovereign violence. Journal of Critical Phenomenology, 2(1), 1–18.

Alton, G. (2020). Toward an integrative model of psychospiritual therapy: Bringing spirituality and psychotherapy together. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 74(3), 159–165.

Angus, L., Watson, J. C., Elliott, R., Schneider, K., & Timulak, L. (2015). Humanistic psychotherapy research 1990–2015: From methodological innovation to evidence-supported treatment outcomes and beyond. Psychotherapy Research, 25(3), 330–347.

Bech, P. (1995). Quality of life measurement in the medical setting. European Psychiatry, 10(S3), 83s–85s.

Becker, W. C. (1986). Applied psychology for teachers: A behavioral cognitive approach. Science Research Associates.

Bergen, J. P., & Verbeek, P.-P. (2021). To-do is to be: Foucault, Levinas, and technologically mediated subjectivation. Philosophy and Technology, 34(2), 325–348.

Berger, P. L. (1974). Some second thoughts on substantive versus functional definitions of religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 13(2), 125–133.

Bevans, S. (2007). John Oman and his doctrine of God. Cambridge University Press.

Beyer, P. (2020). Religion in interesting times: Contesting form, function, and future. Sociology of Religion, 81(1), 119.

Bienenfeld, D. (2006). Psychodynamic theory for clinicians. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Bock, A. M. B., Furtado, O., & de Lourdes Trassi Teixeira, M. (2008). Psicologias: Uma introdução ao estudo de psicologia (14th ed.). Saraiva.

Bowie, F. (2005). The anthropology of religion: an introduction (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Busch, F. N. (2021). Problem-focused psychodynamic psychotherapies. Psychiatric Services, 72(12), 1461–1463.

Cabaniss, D. L., Cherry, S., Douglas, C. J., Graver, R., & Schwartz, A. R. (2013). Psychodynamic formulation (14th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Cain, D. J., Keenan, K., & Rubin, S. (2015). Humanistic psychotherapies: Handbook of research and practice (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association.

Capps, D. (1998). Living stories: Pastoral counseling in congregational context. Fortress Press.

Carvalho, J.-P., Iyer, S., & Rubin, J. (2019). Advances in the economics of religion. Springer.

Cascais, A. F. (2023). Ontotechnologies of the body: Technoperformativity and processes of subjectivation. Philosophy of Engineering and Technology, 43(1), 283–303.

Clay, I., Cormack, F., Fedor, S., Foschini, L., Gentile, G., van Hoof, C., Kumar, P., Lipsmeier, F., Sano, A., Smarr, B., Vandendriessche, B., & Luca, V. D. (2022). Measuring health-related quality of life with multimodal data: Viewpoint. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(5), e35951.

Colarusso, C. A., & Nemiroff, R. A. (1981). Adult development: A new dimension in psychodynamic theory and practice. Springer.

Cox, J. (2006). Guide to the phenomenology of religion: Key figures, formative influences and subsequent debates. Continuum.

Cunha, V. F., Pillon, S. C., Zafar, S., Wagstaff, C., & Scorsolini-Comin, F. (2020). Brazilian nurses’ concept of religion, religiosity, and spirituality: A qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 22(4), 1161–1168.

Dalgalarrondo, P. (2019). Psicopatologia e semiologia dos transtornos mentais [Psychopathology and semiology of two mental disorders] (3rd ed.). Artmed.

Danzer, G. (2018). Therapeutic self-disclosure of religious affiliation: A critical analysis of theory, research, reality, and practice. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 10(4), 398–403.

Dupre, J. (2001). Human nature and the limits of science. Oxford Scholarship.

Efklides, A., & Moraitou, D. (2013). A positive psychology perspective on quality of life. Springer.

Evans, T., Whitehead, M., Diderichsen, F., Bhuiya, A., & Wirth, M. (2001). Challenging inequities in health: From ethics to action. Oxford University Press.

Fayers, P. M., & Machin, D. (2000). Quality of life: Assessment, analysis and interpretation. John Wiley & Sons.

Feist, G. J. (2008). The psychology of science and the origins of the scientific mind. Yale University Press.

Feizi, M., Kamali, Z., Gholami, M., Abadi, B. A. G. H., & Moeini, S. (2019). The effectiveness of existential psychotherapy on attitude to life and self-flourishing of educated women homemakers. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8(237), 1–6.

Flynn, T. (2006). Existentialism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Fonagy, P. (2015). The effectiveness of psychodynamic psychotherapies: An update. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 137–150.

Forrester, J. W. (1972). Churches at the transition between growth and world equilibrium. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, 7(3), 145–167.

Fuentes, A. (2017). Human niche, human behaviour, human nature. Annales. Ethics in Economic Life, 7(5), 1–13.

Fuentes, A., & Visala, A. (2016). Conversations on human nature. Routledge.

Furseth, I., & Repstad, P. (2006). An introduction to the sociology of religion: Classical and contemporary perspectives. Ashgate.

Giglio, A. D. (2022). Suffering-based medicine: practicing scientific medicine with a humanistic approach. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 23(2), 215219.

Glass, J. (2019). Why aren’t we paying attention? Religion and politics in everyday life. Sociology of Religion, 80(1), 927.

Grinde, B. (2018). The evolution of consciousness: Implications for mental health and quality of life. Springer.

Guelfi, J. D. (1992). La mesure de la qualité. Annales Médico-Psychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique, 150(9), 671–676.

Guénoun, T., & Attigui, P. (2021). The therapeutic group in adolescence: A process of intersubjectivation. Child and Adolescent Psychoanalysis, 102(3), 519–542.

Gunning-Schepers, L. J. (1999). Models: Instruments for evidence based policy. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 53(5), 263.

Hazarika, M., & Choudhury, P. (2019). Reflections on and discussions about Luminous Life: A New Model of Humanistic Psychotherapy. Open Journal of Psychiatry & Allied Sciences, 10(1), 87–90.

Henderson, D. K. (1993). Interpretation and explanation in the human sciences. State University of New York Press.

Hergenhahn, B. R., & Henley, T. (2013). An introduction to the history of psychology (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Hinde, R. A. (1976). Interactions, relationships and social structure. McGraw-Hill.

Hoben, M., Banerjee, S., Beeber, A. S., Chamberlain, S. A., Hughes, L., O’Rourke, H. M., Stajduhar, K., Shrestha, S., Devkota, R., Lam, J., Simons, I., Dymchuk, E., Corbett, K., & Estabrooks, C. A. (2022). Feasibility of routine quality of life measurement for people living with dementia in long-term care. JAMDA: Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 23(7), 1221–1226.

Horodecka, A. (2014). The meaning of concepts of human nature in organizational life in business ethics context. Annales. Ethics in Economic Life, 17(4), 53–64.

Hoyrup, J. (2000). Human sciences: Reappraising the humanities through history and philosophy. State University of New York Press.

Hoyt, E. E. (1933). Research in the social problems of old age. Social Forces, 11(3), 398–401.

Hwang, K. (2022). The humanistic approach to aging and the plastic surgeon’s role. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 37(7), 2128–2133.

Iacovou, S., & Weixel-Dixon, K. (2015). Existential therapy. Routledge.

Jacobsen, B. (2007). Invitation to existential psychology: A psychology for the unique human being and its applications in therapy. John Wiley & Sons.

Jones, L. (2005). Encyclopedia of religion. Macmillan Reference.

Judaken, J., & Bernasconi, R. (2012). Situating existentialism: Key texts in context. Columbia University Press.

Kam, C. (2020). Growth in adult ego development and mentalizing emotions for an increasingly multidimensional god image. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 74(4), 250–257.

Kang, L., Ma, S., Chen, M., Yang, J., Wang, Y., Li, R., Yao, L., Bai, H., Cai, Z., Yang, B. X., Hu, S., Zhang, K., Wang, G., Ma, C., & Liu, Z. (2020). Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87(1), 11–17.

Kaplan, R. M., & Hays, R. D. (2022). Health-related quality of life measurement in public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 43(1), 355–373.

Koenig, H., Koenig, H. G., & King, D. (2012). & Carson (Vol. B). A century of research reviewed. Oxford University Press.

Larsen, R. J., & Bus, D. M. (2008). Personality psychology: domains of knowledge about human nature (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Le, T. T. T., Martinent, G., Dupuis-Girod, S., Parrot, A., Contis, A., Riviere, S., Chinet, T., Grobost, V., Espitia, O., Dussardier-Gilbert, B., Alric, L., Armengol, G., Maillard, H., Leguy-Seguin, V., Leroy, S., Rondeau-Lutz, M., Lavigne, C., Mohamed, S., Chaussavoine, L., ... Fourdrinoy, S. (2022). Development and validation of a quality of life measurement scale specific to hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: the QoL-HHT. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 17(281), 1–14.

Lee, E. N., & Mandelbaum, M. (1967). Phenomenology and existentialism. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Levitt, H. M., Surace, F. I., Wu, M. B., Chapin, B., Hargrove, J. G., Herbitter, C., Lu, E. C., Maroney, M. R., & Hochman, A. L. (2022). The meaning of scientific objectivity and subjectivity: From the perspective of methodologists. Psychological Methods, 27(4), 589–605.

Lewis, A. M. (2014). Terror management theory applied clinically: Implications for existential-integrative psychotherapy. Death Studies, 38(6), 412–417.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Marino, L. (1999). Essentialism revisited: Evolutionary theory and the concept of mental disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(1), 400–4011.

Livet, A., & McCluskey, I. (2019). Les thérapies cognitives et comportementales, une coconstruction des soins [Cognitive and behavioral therapies, a co-construction of care]. Soins Psychiatrie, 40(324), 39–42.

Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Tomaso, C. D., Lefrançois, D., Mageau, G. A., Taylor, G., Éthier, M.-A., & Léger-Goodes, T. (2021). Existential therapy for children: Impact of a philosophy for children intervention on positive and negative indicators of mental health in elementary school children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12332.

Maltby, J., Day, L., & Macaskill, A. (2010). Personality, individual differences and intelligence (2nd ed.). Pearson Education.

Maynard, E. A., & Snodgrass, J. L. (2015). Understanding pastoral counseling. Springer.

McMullin, R. E., & Giles, T. R. (1981). Cognitive-behavior therapy: A restructuring approach. Grune & Stratton.

McNally, R. J. (2011). What is mental illness? Belknap Press.

Mental health of school children. (1906). JAMA The Journal of the American Medical Association, XLVII(1), 39–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1906.02520010047005

Moore, A. (1967). Existential phenomenology. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 27(3), 408–414.

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & Lombardo, E. (2004). Cognitive-behavioral case formulation and treatment design: A problem-solving approach. Springer.

Nye, M. (2008). Religion: The basics. Routledge.

Obregon, S. L., Lopes, L. F. D., Kaczam, F., da Veiga, C. P., & da Silva, W. V. (2022). Religiosity, spirituality and work: A systematic literature review and research directions. Journal of Business Ethics, 179(1), 573–595.

Oliver, J., Huxley, P., Bridges, K., & Mohamad, H. (2005). Quality of life and mental health services. Taylor and Francis.

Olson, D. V. A. (2019). The influence of your neighbors’ religions on you, your attitudes and behaviors, and your community. Sociology of Religion, 80(1), 147167.

Oman, J. (1919). Grace and personality (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Oman, J. (1931). The natural and the supernatural. Cambridge University Press.

Oman, J. (1941). Honest religion. Religious Book Club.

Owen, I. R. (2015). Phenomenology in action in psychotherapy: On pure psychology and its applications in psychotherapy and mental health care. Springer.

Paloutzian, R. F., & Park, C. L. (2005). Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality. Guilford Press.

Paloutzian, R. F., & Park, C. L. (2014). Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (2nd ed.). Guilford.

Piotrowski, N. A. (2010). Psychology & mental health. Salem Press.

Rasmussen, P. R. (2005). Personality-guided cognitive-behavioral therapy. American Psychological Association.

Reynolds, J. (2006). Understanding existentialism (understanding movements in modern thought). Acumen.

Rogers, C. (1995). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Mariner Books.

Rogers, C., & Yalom, I. D. (1995). A way of being. Mariner Books.

Röthl, M. (2021). Modes of subjectivation: About dispositive-theoretical borrowings and ’urgencies’ of a cultural-analytical reading. Schweizerisches Archiv Fur Volkskunde, 117(1), 59–73.

Sajid, M. S., Tonsi, A., & Baig, M. K. (2008). Health-related quality of life measurement. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 21(4), 365–373.

Salmanian, M., Ghobari-Bonab, B., Hooshyari, Z., & Mohammadi, M.-R. (2020). Effectiveness of spiritual psychotherapy on attachment to God among adolescents with conduct disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 12(3), 269–275.

Schneider, K. J., Pierson, J. F., & Bugental, J. F. T. (2015). The handbook of humanistic psychology: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Schrag, C. O. (2012). Celebrating fifty years of the Society for Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy. Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 26(2), 86–92.

Schulenberg, S. E. (2016). Clarifying and furthering existential psychotherapy: Theories, methods, and practices. Springer.

Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 65(2), 98–109.

Sheldrake, P. (2007). A brief history of spirituality. Blackwell.

Sirgy, M. J. (2002). The psychology of quality of life. Springer.

Sirgy, M. J. (2021). The psychology of quality of life: Wellbeing and positive mental health (3rd ed.). Springer.

Smart, N. (1998). The world’s religions. Cambridge University Press.

Solomon, R. C. (2005). Existentialism (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Spinelli, E. (2014). Practising existential therapy: The relational world. SAGE.

Spitzer, R. L. (1999). Harmful dysfunction and the DSM definition of mental disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(3), 430–432.

Stein, D. J., Phillips, K. A., Bolton, D., Fulford, K., Sadler, J. Z., & Kendler, K. S. (2010). What is a mental/psychiatric disorder? From DSM-IV to DSM-V. Psychological Medicine, 40(11), 1759–1765.

Strouse, T. B., & Bursch, B. (2018). Psychological treatment. Hematology/oncology Clinics of North America, 32(3), 483–491.

Stump, R. W. (2008). The geography of religion: Faith, place, and space. Rowman & Littlefield.

Tanyi, R. A. (2002). Towards clarification of the meaning of spirituality. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 39(5), 500–509.

Taylor, K. W. (1942). Education for family life. Journal of Heredity, 33(9), 335–336.

Teoli, D., & Bhardwaj, A. (2022). Quality of life. StatPearls.

Ukuekpeyetan-Agbikim, N. A. (2014). Current trends in theories of religious studies: A clue to proliferation of religions worldwide. Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(7), 27–46.

Vincent, S. (2016). Being empathic: A companion for counsellors and therapists. CRC Press.

Vos, J., Craig, M., & Cooper, M. (2015). Existential therapies: A meta-analysis of their effects on psychological outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(1), 115–128.

Weatherhead, L. D. (1999). The will of God (Rev. Ed.). Abingdon Press.

Weber, M., Fischoff, E., & Swidler, A. (1993). The sociology of religion. Beacon Press.

Whitehead, M. (1992). The concepts and principles of equity and health. International Journal of Social Determinants of Health and Health Services, 22(3), 429–445.

Whitehouse, H. (2004). Modes of religiosity: A cognitive theory of religious transmission. Altamira Press.

Wright, J. H., Brown, G. K., Basco, M. R., & Thase, M. E. (2017). Learning cognitive-behavior therapy: An illustrated guide (2nd ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Yinger, J. M. (1957). Religion, society and the individual: An introduction to the sociology of religion. Macmillan.

Zareba, S. H., Sroczynska, M., Cipriani, R., Choczynski, M., & Klimski, W. (2022). Metamorphoses of religion and spirituality in central and eastern Europe. Routledge.

Ziaee, A., Nejat, H., Amarghan, H. A., & Fariborzi, E. (2022). Existential therapy versus acceptance and commitment therapy for feelings of loneliness and irrational beliefs in male prisoners. European Journal of Translational Myology, 32(1), 10271: 1–9.

Zieske, C. (2020). A brief history and overview of existential-phenomenological psychology. American Journal of Undergraduate Research, 77(2), 45–58.

Zis, P., Varrassi, G., Vadalouka, A., & Paladini, A. (2019). Psychological aspects and quality of life in chronic pain. Pain Research and Management, 2019, 8346161.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Doctoral Program in Ministry at Seminary Capital & Graduate School of Lancaster Bible College (Lancaster, Pennsylvania) and Faculdade Teológica Sul Americana (Londrina, PR, Brazil) for their assistance in the development of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This research does not involve human participants and/or animals.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Serra, G.L.O. Existential Psychology and Religious Worldview in the Practice of Pastoral Counseling. Pastoral Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-024-01136-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-024-01136-9