Pacifico Silano by Cassie Packard

Photographs that memorialize queer archives.

May 8, 2024

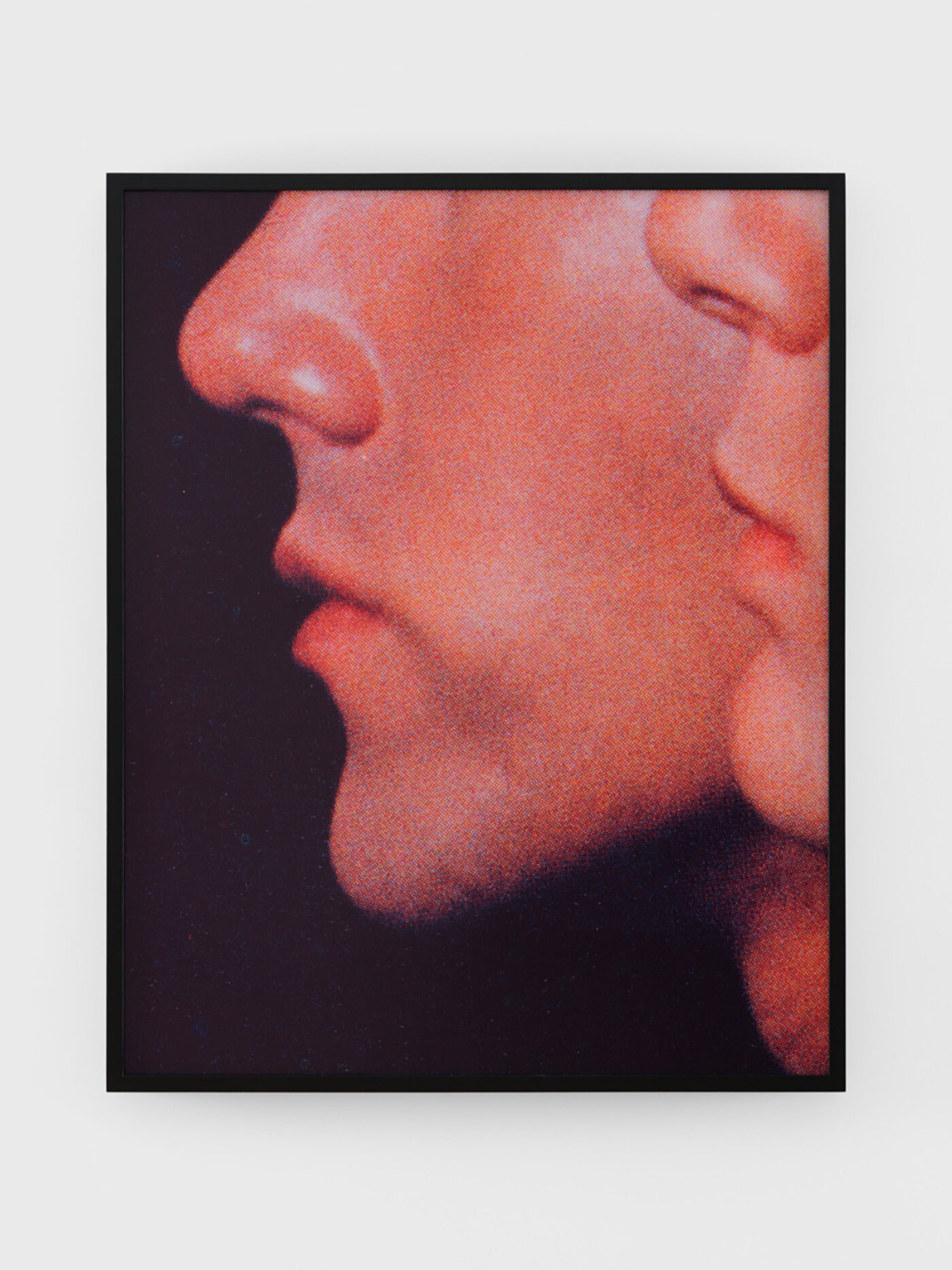

Cruising archives of queer masculinity and gay desire, New York City–based artist Pacifico Silano rephotographs men in gay soft-core magazines from the 1970s and early ’80s, a period of significant cultural-identity formation for a gay male public in the United States on the eve of the HIV/AIDS crisis. Silano’s “grids” of images allude to the fact that AIDS was initially called “Gay-Related Immune Deficiency [GRID],” when it was believed exclusively to affect gay men. As the artist fragments erotic found figures and scenes with close crops, he lingers on torn pages and paper grain. His portraits are all the more seductive for the way his technique brings viewers closer to the subject and enhances the material qualities of the page, highlighting print media’s specific magnetism.

Silano’s complex images are at once repositories of pleasure and sites of mourning. As he memorializes queer archives and traces lineages of gay male desire, he also brings a critical eye to his raw material by exploring the “undercurrents of potential violence” tied up with the fetishization of tropes of US masculinity. On the occasion of his solo show Psychosexual Thriller at Island Gallery, Silano spoke with me about rephotographing in response to erasure, the utility of Trojan horses, and the ways images change over time.

Cassie Packard At the outset of your career, you were predominantly making narrative photographs. What prompted you to pivot to appropriation? I normally associate appropriation art with a cool, detached quality; but your works have warmth—heat, even.

Pacifico Silano When I was in graduate school I studied under both Sarah Charlesworth and Penelope Umbrico. The experience really transformed my thinking of what a photograph could be. I started to reconsider my relationship to images that already exist in the world and how they can be embedded with such complex meaning. I have a real love for the surface of images and their clichés, but I believe there is actually a lot of depth there. Photographs are constantly shifting their meanings over time. They’re slippery and hard to pin down. So that warmth you sense is from a deep admiration for the medium.

Pacifico Silano, Turned On, 2024, dye sublimation print in artist frame, 16 × 21 × 1.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

CP You’ve mentioned an uncle who died of complications from HIV/AIDS and subsequently disappeared from the family archives. I’m wondering if your decision to rephotograph men in gay magazines from the ’70s and ’80s, when he was alive, is a means of refusing his erasure or if the gesture is otherwise colored by the loss of so many in that generation to HIV/AIDS.

PS Initially, it was a workaround. Growing up, I only had one Polaroid of my uncle; I wanted to talk about that loss and erasure but had no source material to work with. It was a deeply personal entry point that became more broadly about a generation because of the circumstances. Conceptually, it also made sense to work with vintage gay erotica because when I was growing up my parents owned and operated a porn store called Undercover Pleasures. It’s part of my biography and has informed my relationship to the source material in a unique way. The store normalized pornography for me because I saw it as commerce and a way to make a living—so much so that I often forget that people make snap judgments of me and the work that I do because of where the images come from. I’ve had public art commissions canceled as a result. But I really believe there is a cultural significance to these magazines being preserved; they’re both snapshots of the distant past and surprisingly contemporary.

CP Was the censorship more in response to the pornographic or queer contexts?

PS It was a combination of both. I had a public art commission in Miami that decided, after I had spent the better part of a year making new work, that they didn’t feel comfortable showing it. I was recontextualizing imagery from gay magazines to talk about loss and longing in relation to HIV/AIDS. The work was very tame, and there wasn’t anything scandalous. They started censoring and removing works from the final edit. The press release also became an issue for them because they didn’t want the word queer to appear anywhere in it. More recently, there was another public art commission in NYC that also fell through for similar reasons. But this time I wasn’t as surprised. People are still very socially conservative, even in places like New York.

CP That is really disappointing. I was thinking about how your collecting of vintage, soft-core gay magazines—not to mention rephotographing them—feels like such an assertion of this material’s value. The practice connects you to a long legacy of queers safeguarding queer ephemera for our own archives, even as the logics of dominant archives suggested that we didn’t—or shouldn’t—exist. I’d love to hear more about your relationship with the magazines you collect and use as source material, and your connection with queer archives more broadly.

PS I think it’s fascinating to think about these magazines and their power within the history of queer archives. They were quite literally meant to be discarded, and yet they have managed to stick around all these years later! I always say that archives are not neutral spaces. They’re all about choosing what to hold on to and what to omit. I’m always seeing something new in the source material in that images reveal themselves to me over time. There are magazines in my collection that I have had for over a decade, and I think I’ve seen everything there is to see. Then I’ll randomly turn to a page and see something that becomes the centerpiece of my next exhibition. It’s always like that. Our relationships to photographs and their cultural meanings are always shifting and changing, depending on how we’re looking at the world at that specific moment. It’s why there is a real value in holding onto material of the past.

Pacifico Silano, Untitled (Marine), 2024, dye sublimation print in artist frame, 42 × 52 × 1.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

CP So many currents of desire run through your work. How are you using desire as a tool, and how is it perhaps in turn using us? Some of the men you depict are dressed as cops. I’m curious about the frictions that arise when we find ourselves desiring what doesn’t neatly align with our visions of ourselves and our politics, and whether, in a queer context, such desires can be understood as subversive, as they are often characterized.

PS I think of my work as a Trojan horse: an object of desire that can become sinister the longer you sit with it. The work is full of contradictions with various ways to be read. It’s not one thing or another; two things can be true at the same time. You can be seduced and repulsed in equal measure. There is a real tension just below the surface of an image I make with undercurrents of potential violence that oftentimes gay men normalize. In a lot of the source material there are men acting out roles of authority and dominance through the fetishization of uniforms, such as cowboys, soldiers, and police officers. These are archetypes of American masculinity read through a queer lens. They can be read as subversive or transgressive depending on who you are and what you bring to it. It’s this gray area that my work thrives in.

CP You pull images from magazines that historically marginalized or excluded nonwhite subjects. Jasbir Puar, writing about hegemonic homosexuality, has highlighted a false binary in which “the homosexual other is white, the racial other is straight.” In your practice, how are you thinking about or grappling with the phenomenon that Puar describes?

PS I’m interested in the politics of desire and how gay men wield it through the way they conform their bodies and the way they dress, talk, and act. I think a lot about this moment in time and how that informs my relationship to the images I work with. This body of work is about the thin line between sex and violence with America as the backdrop. I can’t talk about those themes without tackling the subject of whiteness. It’s ever-present in the source material and what the art is about. I have a certain level of self-criticality when making this work, and at times it feels like a self-interrogation of my own identity. One of the most important functions of art is to hold up a mirror to society. That mirror can feel uncomfortable to my audience, and even to me, but I think it’s an important discomfort to continue to explore. But I try to sneak some humor in there when I can. I have a piece in this show about gay narcissism that’s inspired by the movie American Psycho. It’s dark humor, but it’s in there.

Pacifico Silano, Body Heat, 2024, dye sublimation print in artist frame, 42 × 52 × 1.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

CP On that note, I’d love to hear about the origin of the show’s title, Psychosexual Thriller.

PS I watch a lot of movies, and I’m always looking to them for some kind of inspiration in my own work. Some of my favorite directors are Paul Verhoeven, Michael Haneke, and David Lynch. I started to see similarities between my new work and this genre of psychosexual filmmaking. Many of these new pieces explore themes about the darker side of intimacy, power, and the threat of danger that comes with all of that. I think of my show titles as a bit of a roadmap to viewing my work.

Pacifico Silano: Psychosexual Thriller is on view at Island Gallery in New York City until May 11.