William J. Barker

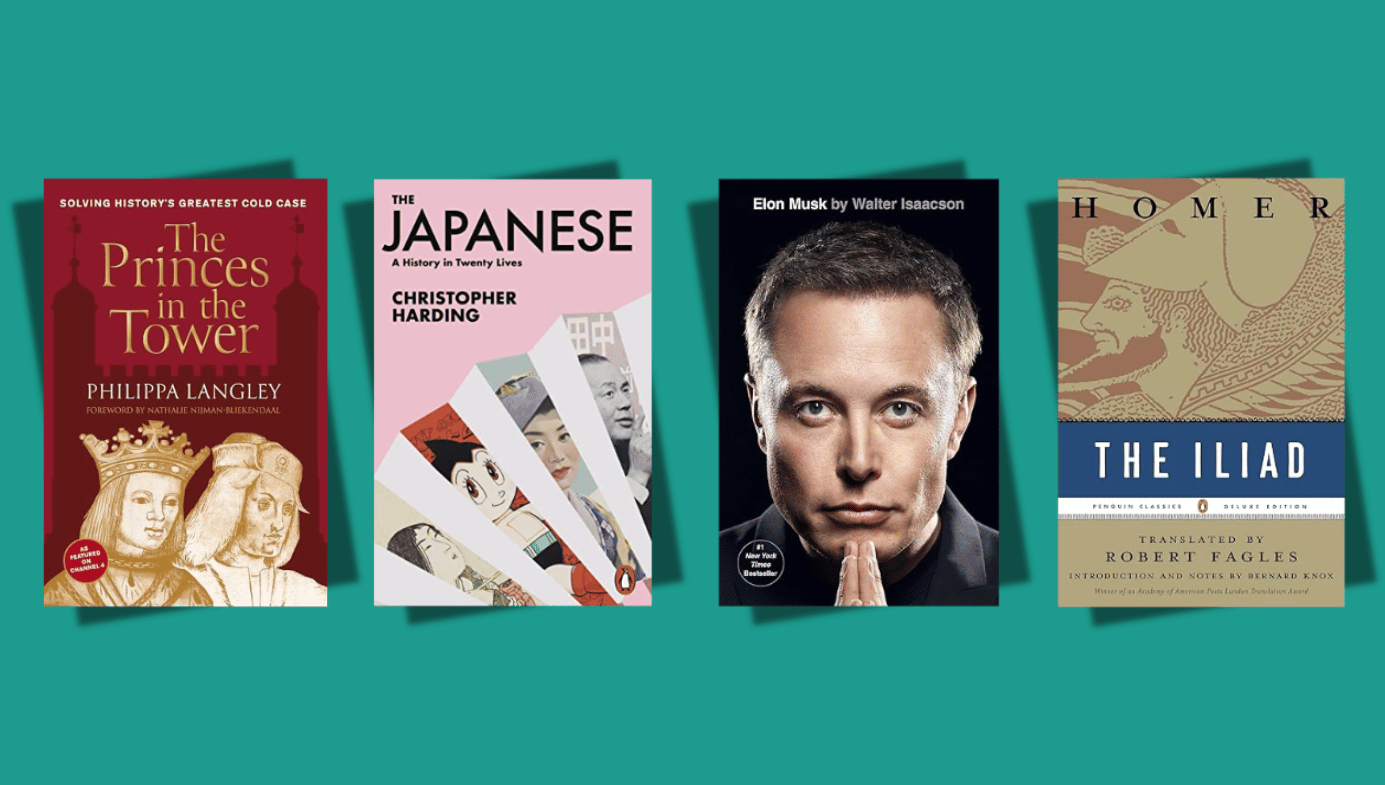

I was amazed by how similar this classic of Western literature is to modern-day action movies. Oxford’s Professor of Poetry A.E. Stallings, got it right when she called The Iliad “the bloody prequel” to The Odyssey. In the chapter I just finished, the Greek and Trojan armies engage in a tug of war for the body of Achilles’ best friend, Patroclus, which takes the better part of twenty pages. Two seas of spear-waving and shield-thumping warriors are crashing against each other again and again, creating a bigger and bigger junk-pile of bloody, severed, and hacked arms and heads and crushed breastplates and helmets at their feet, as they swirl around the body of the hero lying slain at the centre of the battlefield. Homer’s poetic and grand-scale ultra-violence reminds me of the battles in my favourite blockbusters like Star Wars, Zack Snyder’s Justice League, and The Avengers. The ancient poet is a connoisseur of action.

Claire Lehmann

I've never been a fan of Elon Musk. But I am a fan of Walter Isaacson, so I picked up this book when browsing a bookshop recently. And I'm glad I did. Each chapter in Isaacson's 688-page volume has an unrelenting cadence, capturing the intensity and energy of its subject. Far from being a hagiography of Musk, Isaacson clearly documents his impulsivity, recklessness, and cruelty to subordinates. Nevertheless, the book also captures the sincerity of Musk's values, which are in many ways those of an Enlightenment Liberal. A believer in democracy, free speech, innovation, and progress, Musk's overarching mission is to preserve human civilization by making it interplanetary. Yet it's the combination of a transcendent vision and hyper-focused attention to detail that has made Musk's businesses successful. A particularly memorable chapter details Musk's strategy of increasing Tesla's manufacturing capacity to 5,000 cars per month by setting up a makeshift factory line on an incline in a car park, using gravity as a conveyor belt (the strategy was successful). I would be lying if I said that I did not come away from the book in awe of Musk's achievements and annoyed with myself for not having learned about them before.

Jonathan Kay

“I shall rehearse you the dolorous end of those babes, not after every way that I have heard, but after that way I have heard by such men and by such means as me thinketh it was hard but it should be true.” So wrote Sir Thomas More (1478–1535) in a tract purporting to explain the deaths of 12-year-old Edward V and his younger brother Richard at the Tower of London following the English succession crisis of 1483.

Anyone familiar with Shakespeare’s historical tragedies will know exactly who “such men” were: agents of the boys’ ruthless uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who’d just seized the throne and now sought to cleanse England of other royal claimants. Thus did Richard III become remembered as one of the great monsters of British history.

But as independent researcher Philippa Langley persuasively argues in her new book, The Princes in the Tower, there have always been serious problems with this narrative. It’s notable that More himself never published his gossip-informed theory, which suggests he wasn’t sure if it was actually true. And its popularisation years later seems to have owed much to the propaganda needs of the Tudor usurper Henry VII, whose victory at Bosworth Field ended Richard III’s brief reign.

Henry was a paranoid, control-obsessed autocrat who gutted the late-sixteenth-century documentary record in a bid to burnish his own (highly dubious) claim to the throne. The story that would later inspire the plot of Shakespeare’s Richard III—which helpfully consigned two rival claimants to the grave, and Henry’s immediate predecessor to disgrace—suited the Tudors’ public-relations requirements perfectly.

A little too perfectly, Langley argues. She is very much a Ricardian—which is to say, a defender of Richard III—as well as the founder of something called the Missing Princes Project. Lest readers be put off by my description of the author as an “independent researcher” (a designation that summons to mind self-published authors with elaborate theories about the fate of JFK’s brain), I will report that her analysis of the available information is detailed and credible (although her decision to style the book in the manner of a formal police investigation does grow tiresome at points).

And so what did become of those imprisoned “babes” in the Tower? Langley leans heavily on (legitimately) ground-breaking documentary discoveries by her Dutch collaborators, which support the idea that the two boys never died in 1483 at all, but rather were hustled out of England—at Richard III’s behest, it should be added—by no less an aristocrat than John Howard, Duke of Norfolk.

Following this, the theory goes, the boys laid low on the continent for a few years (with the help of their staunchly Yorkist aunt, Margaret of Burgundy) before returning to history’s stage as what Henry VII insisted (successfully, for the most part) were shameless pretenders named Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck.

Like all Ricardians, Langley has her own axes to grind. But her focus on continental sources (including an obscure but tantalising accounting document newly unearthed from the Archives Départementales du Nord in Lille, France) offers a promising line of inquiry that may yield more new evidence in coming years. Many credible continental sources, including men and women who met the two now-teenage princes in Portugal, France, and the Low Countries in the late fifteenth century, clearly believed they were the real deal, and there are plenty of surviving sources to prove it.

It seems doubtful that Richard will ever escape the mark of infamy branded upon him by Shakespeare (and, more recently, Oxford Films). But at the very least, Langley has shown us that the case against Richard III is, in the procedural idiom of criminal law, marred by many, many reasonable doubts.

Iona Italia

I recently watched the miniseries Shogun, created by Rachel Kondo and Justin Marks, based on the 1975 novel of the same name by James Clavell. The show’s lush portrayal of life in early 17th-century Japan reignited my interest in Japanese history and culture. (I read Clavell’s novel back in 1980, after watching the original BBC miniseries based on the book, starring Richard Chamberlain and Toshirô Mifune.)

My investigations led me first to Amy Stanley’s book, Stranger in the Shogun’s City: A Woman's Life in Nineteenth-Century Japan, a fictionalised account that draws heavily on contemporary sources. Stanley's protagonist is dissatisfied with her restricted life as the wife of a farmer in a remote rural town and yearns for the richer cultural offerings of Tokyo, but her efforts to find freedom and fulfilment are stymied by the restrictions of a society that is mercilessly hierarchical and suffocatingly bureaucratic. It’s a vivid and immersive portrayal of a free spirit battling against a deeply claustrophobic and conservative society.

How that society developed is the topic of historian Christopher Harding’s book, The Japanese: A History in Twenty Lives. Presenting a series of brief biographies from people living at different points in history can be a very effective and engaging way of telling the story of a nation, as I already knew from reading Sunil Khilnani’s exceptional Incarnations: India in 50 Lives. Harding’s protagonists include travellers, poets, Nō and kabuki players, Buddhist monks and court attendants, as well as samurai, shoguns, and emperors. Spanning a period from the earliest written sources to the present day, the book provides fresh insights into the roots of Japan’s fascinating, intricate, aesthetically restrained, conformist and militaristic culture.