The four-kilometer Samal Island-Davao City Connector (SIDC) Project is one of the 12 mega-bridge projects listed in President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.s’ Build, Better More (BBM) infrastructure program, which he mentioned in his 2023 state of the nation address (SONA).

The bridge, approved by the National Economic and Development Authority in November 2019, was originally targeted for completion by 2027. It will cross Pakiputan Strait to connect mainland Mindanao via Davao City and Samal, Davao del Norte, reducing travel time from 50 minutes via ferry to just 4.5 minutes.

But there has not been much progress since Marcos led the ceremonial groundbreaking of the P23-billion China-funded bridge in October 2022. Construction has been delayed due to right-of-way (ROW) issues on one end and “right of nature” concerns on the other, preventing implementers to go full speed ahead.

Samal Island-Davao City Connector Project’s perspective design. Photo from the Department of Public Works and Highway’s Facebook page

Construction was suspended in January 2023 due to right of way issues. The Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) admits that the civil works are not yet in full swing because of the unresolved ROW acquisition issues.

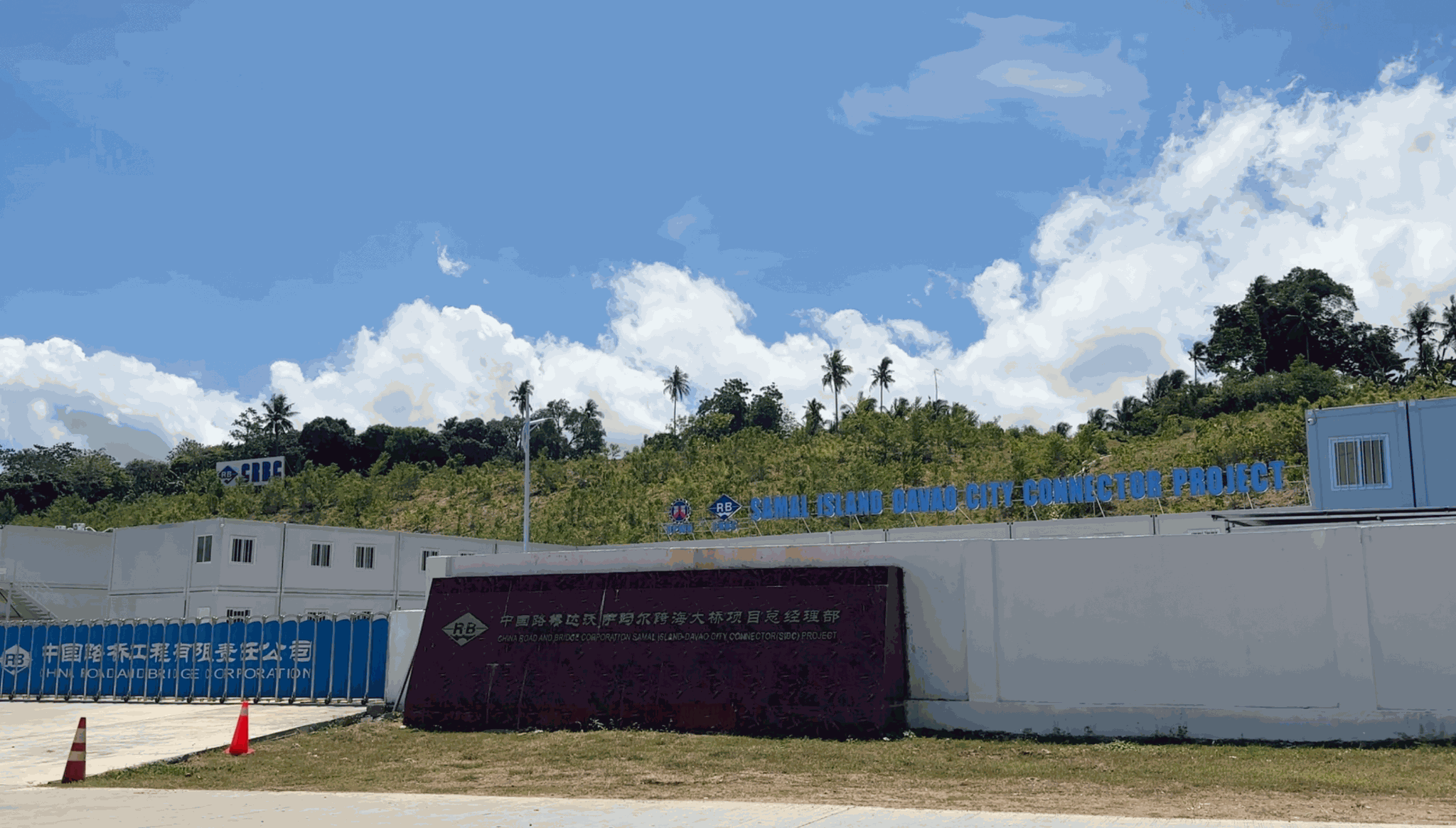

In April, Chinese contractor China Road and Bridge Corporation (CBRC) started work on the deep foundations for the bridge’s land and marine viaducts.

“If you say that it’s full blast, meaning, walang problema. Sa Davao side, marami pang dapat i-acquire na property. So, ang nagagalaw pa lang namin is only those areas na acquired na, nabayaran na (there is no problem. In the Davao side, many properties have yet to be acquired. So, what we are operating on for now are those areas that have been acquired, already paid),” SIDC Project Manager Joey Tulaylay said in an April 22 press briefing.

Construction activities by the China Road and Bridge Corporation on the Samal Island side on April 22. Photos by Valerie Joyce Nuval

A promised mega-bridge

“Under the Mega-Bridge Program, 12 bridges totalling 90 kilometers will be constructed, connecting islands and areas separated by waters. The program notably includes the Bataan-Cavite Interlink Bridge and the Panay-Guimaras-Negros Island Bridges, each spanning 32 kilometers, and also the Samal Island-Davao City Connector Bridge,” Marcos said in his second SONA in July last year.

It was a carry-over from the Duterte administration’s P9-trillion Build, Build, Build infrastructure program.

One of the 185 high-impact Infrastructure Flagship Projects (IFPs) under the BBM program, the extradosed bridge will have landing points at the Samal Circumferential Road in Barangay Limao in the Island Garden City of Samal (IGaCos) and between R. Castillo and Daang Maharlika junction in Buhangin, Davao City.

An extradosed bridge uses cables instead of additional foundations to support its structure, giving enough clearance for ships to pass through.

According to the DPWH, the toll-free, four-lane bridge “will provide ease of access to tourism activities in IGaCos, enhance community access to employment, education and other social services and alternative routes during emergency situations and disasters.”

Road rights, environmental concerns

The formulation of the project’s Detailed Engineering Design, a requirement before the construction phase can start, has also been suspended for a year now because of ROW problems.

Even as the public works agency scrambles to catch up in hopes of completing the bridge before the term of Marcos Jr. ends in 2028, the project still has “right of nature” issues to sort out.

“On their part, it’s the right of way. What we keep on saying [is] it’s the right of nature,” said Carmela Marie “myLai” Santos, director of the Ateneo de Davao University – Ecoteneo and co-secretariat at the local civil society group Sustainable Davao Movement (SDM), when asked in a May 1 interview with VERA Files about the cause of the project’s delays.

She said Ecoteneo and SDM are willing to exhaust all means to push for the realignment of the bridge because they believe there are cheaper, shorter and less destructive alternatives.

“Clearly, there are other available options that will spare the marine protected area of Hizon and the Paradise Reef. Aralin nilang mabuti ‘yung ibang options nila (They should thoroughly study other options),” Santos said as she reiterated her groups’ calls for the realignment of the bridge.

The connector’s landing point in Davao is located in Barangay Hizon, a marine-protected area included in the city’s Comprehensive Land Use Plan for 2018 – 2028.

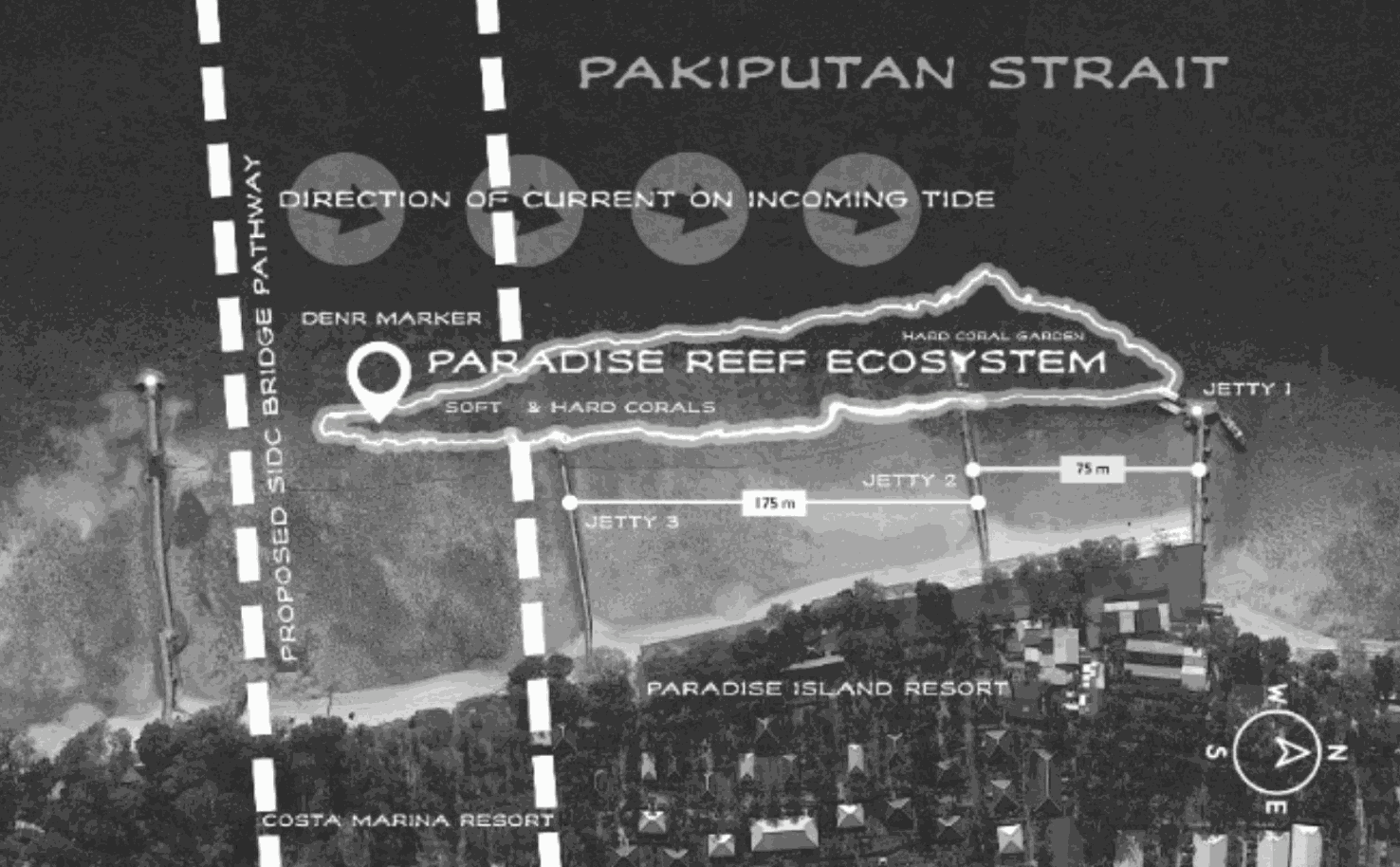

In Samal, the bridge lands along the coast of the Costa Marina Beach Resort next to the Paradise Island Park Resort in Barangay Limao.

Paradise Reef, a shelter to 79 species of hard corals, 26 species of soft corals and 100 species of fish, is within the vicinity of these two resorts owned by the Lucas-Rodriguez family.

Paradise Reef Ecosystem illustration by Dr. John Lacson and the views from the Paradise Island Park and Beach Resort

“We’ve been protecting the reef for 50 years since Paradise has been here. We have been very protective of that reef until now. So, we were surprised that [it is] lacking studies and still they pushed through with the project,” Julian Rodriguez, manager of the Paradise Island Park and Beach Resort, said in an April 22 interview.

Paradise Island Park and Beach Resort manager Julian Rodriguez points to the bridge construction in Davao City. Photos by Valerie Joyce Nuval

Shorter, cheaper alternative

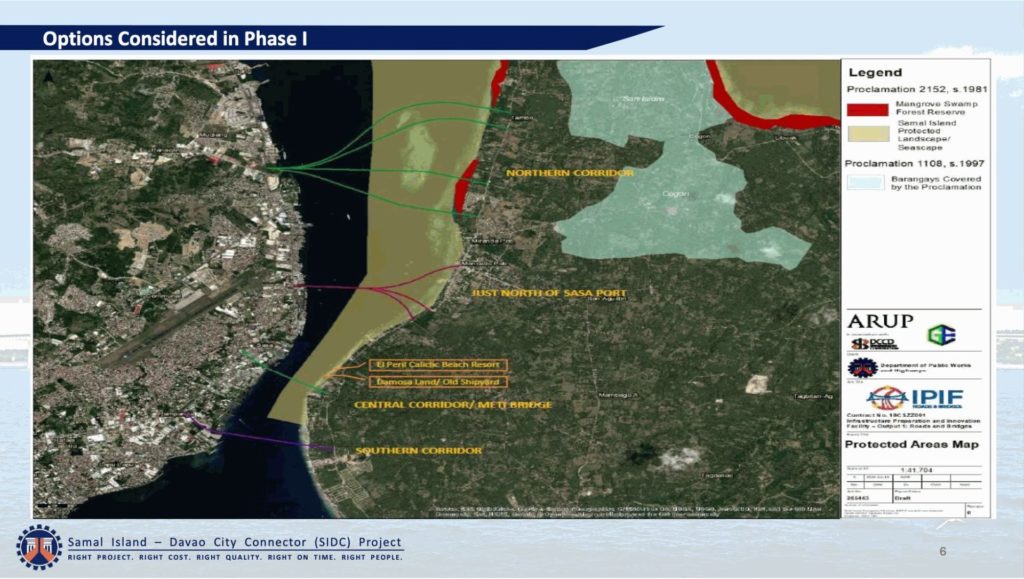

The Lucas-Rodriguez family, Ecoteneo and SDM all call for the landing site to be realigned to an old shipyard called Bridgeport. This is in line with a 2016 study by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) that proposes a shorter and much cheaper bridge.

In 2019, the Lucas-Rodriguez family commissioned a team of marine biologists to conduct a biophysical assessment of three proposed landing sites and found that Bridgeport “has the least biologically productive area,” thus, the best option.

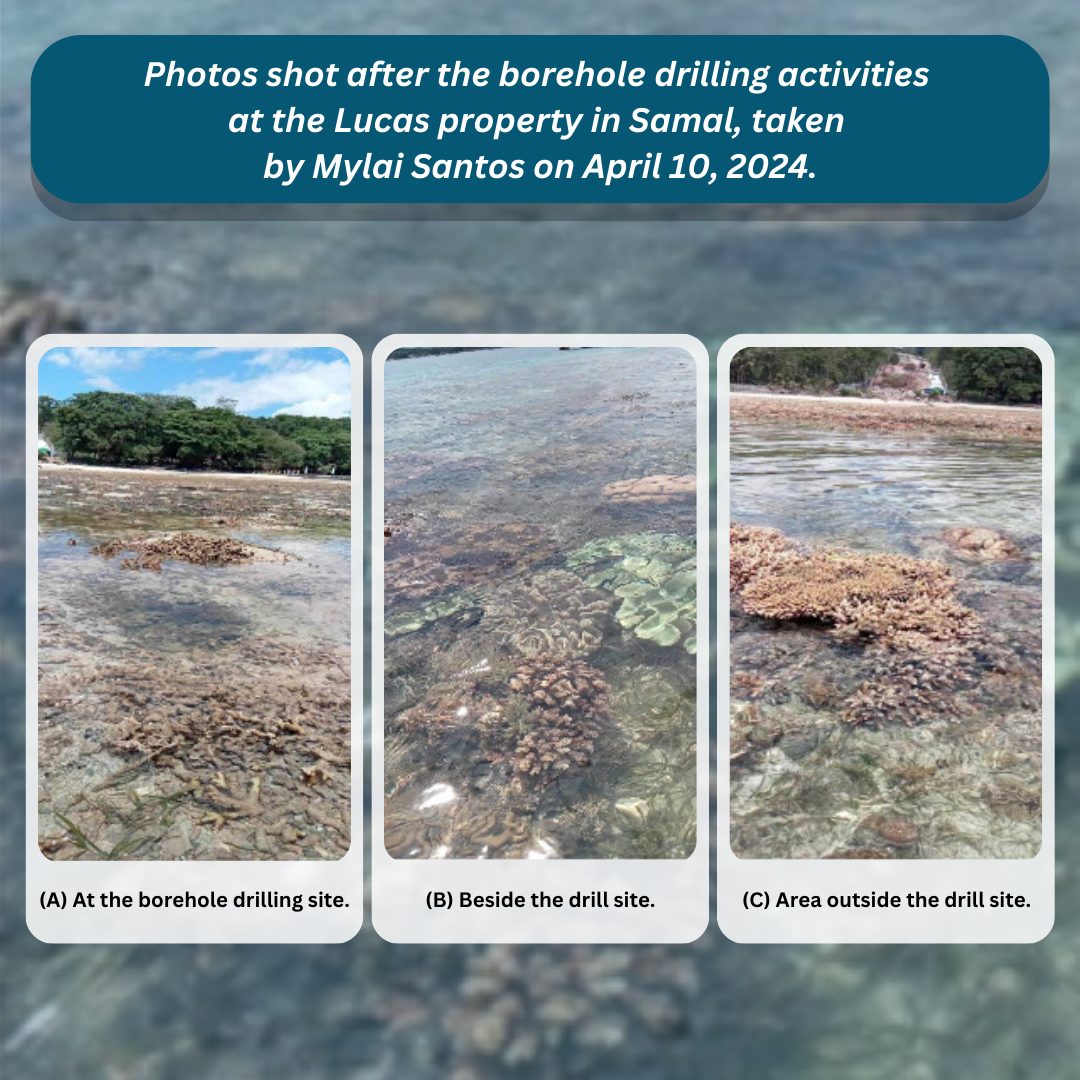

Contrary to the DPWH’s claim that the corals in Paradise Reef “are in poor condition,” the study concluded that the SIDC “will definitely cause irreparable, irreversible and incalculable damage to the best marine ecosystem in Samal Island that will have adverse ecological impact to the Davao Gulf as Key Marine Biodiversity Area.”

The DPWH, however, insists that the current alignment (southern corridor) is the only one that lies outside the National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS).

Santos stressed that the entire Samal Island itself is a protected area, having been declared as a “mangrove swamp forest reserve” under Presidential Proclamation 2152, s. 1981 signed by then president Ferdinand Marcos Sr. She claimed that while it has not been included in the e-NIPAS, there has been no move yet for its delisting.

She asserted that even before the construction started, the borehole drillings for soil samplings have already caused irreversible damage to the corals both in Davao and Samal.

The DPWH said the agency has mitigating measures such as planting of 100 trees for every tree cut, convening a multipartite monitoring team, as well as using steel craneway to minimize damages.

Exhausting all means

In March last year, the Rodriguez family filed a petition for a temporary restraining order before the Supreme Court to stop the construction of the project. It is still awaiting the High Court’s decision.

The petition calls for a review of the project’s procedures and documents, including the DENR’s issuance of an Environmental Compliance Certificate (ECC).

“It’s a mandamus case [to] more or less review the procedures or the requirements, and the studies that [were] done for them to be able to get an ECC kasi may NIPAS, eh (because there is NIPAS). There are certain…things that are disallowed if there is a protected area involved,” Rodriguez said.

The family brought the case to the High Court after the Court of Appeals dismissed the petition because it bypassed the Municipal Trial Court and Regional Trial Courts.

The DPWH reiterated that its work continues despite the pending case.

SDM is also planning to file a writ of kalikasan before the Supreme Court in the coming months. The writ of kalikasan is a legal remedy used in cases where there are supposed violations against the people’s constitutional right “to a balanced and healthful ecology in accord with the rhythm and harmony of nature.”

“[We are aiming] for a TEPO, Temporary Environmental Protection Order, leading to a cease and desist [order] sana (hopefully). Considering na… extensive na ‘yung damage actually even without the construction,” Santos added.

Santos has also been sending appeal letters to senators for an investigation into the environmental concerns surrounding the SIDC project.

“I think sustainable infrastructure is something that incorporates or recognizes nature in the goals and objectives…. When you plan for infrastructure, you plan it for [the] people. Make it people-centered and nature-based,” Santos, an urban planner herself, answered when asked how she envisions sustainable infrastructure.