The Story Behind The Architecture and Construction of St. Peter's Basilica

Front Facade of St. Peter’s from St. Peter’s Square. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

At the heart of Vatican City, St. Peter's Basilica stands as a monumental testament to Renaissance architecture's ingenuity and the Christian faith's enduring spirit. This iconic structure has captivated visitors and worshippers for centuries with its imposing façade, towering dome, and sacred interior. Its architectural history is a tapestry woven from the visions of legendary architects such as Bramante, Michelangelo, and Bernini. Each contributed their genius to the Basilica's construction, leaving a lasting legacy.

Experiencing St. Peter’s

I first saw St. Peter's on a pilgrimage to Europe after graduating from architectural school in 2013. With only a few hours of sleep, I got off the train in Rome at about 7:00 a.m. on a hot summer day. The sun was low in the sky and shone directly into my eyes as I exited the train. The air was already heavy and dusty.

Experiencing St. Peter's is almost disorienting. The scale of the building, the number of sculptures, the ornate detailing, the paintings, and the level of craftsmanship were overwhelming. As I approached St. Peter's Square, I had to stop to process the scale of the site. I began to question. How long did it take to build this place? How many people worked on it? How was the construction funded?

Over the past decade, I’ve dug deeper into the history, people, and circumstances that brought this work of architecture to fruition. It was fascinating to see the story of St. Peter’s unfold in parallel with the history of Western civilization. This article is my attempt to communicate what I have learned and seen. It explores the architectural evolution of St. Peter's Basilica, offering insights into its design, construction, and people responsible for its creation.

Front Facade of St. Peter’s from St. Peter’s Square. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

St. Peter’s Square with ancient Egyptian obelisk brought to Rome in the 1st century. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

The History of Christianity, Rome and the Early Basilica

To fully understand St. Peter's, it is critical to understand the history of Rome and the Catholic faith. The story of St. Peter's begins with the start of Christianity. Christianity was not an accepted religion at the time of its conception. It was a humble and modest religion. The practices of the religion were not exclusive to a particular group of people; they were available to every man, and every man had access to Heaven. The promise of an afterlife attracted many followers, and the religion slowly spread.

Constantine, emperor of Rome, eventually made Christianity acceptable. At that point, it expanded across the Roman Empire. Constantine built the original St. Peter's in the 4th century. It was built over the alleged burial site of St. Peter and stood for over 1,000 years. The Roman Empire fell in 476 AD, and Europe entered the Dark Ages.

During the Dark Ages, faith and politics became entangled. Many activities associated with the Church were filled with pageantry and self-indulgence. The original message of Christianity became diluted. Confusion and skepticism began to set in. Rome decayed, and this once prosperous city would not recover until the Renaissance.

Renaissance in Rome

By the 15th century, old St. Peter's was in complete disrepair. Nicholas V.'s election brought new life to Rome and is credited with bringing the Renaissance to Rome. Nicholas was a humanist who sincerely cared about his people. He was an intellectual who loved philosophy and had a passion for building. Part of reinvigorating Rome was re-establishing the Church and faith in Christianity. To do this, he imagined a new Basilica on Vatican Hill. He began generating plans for his vision.

The plans would remain only sketches on paper until Pope Julius II was appointed. Julius II had a vision for the greatness of Rome's papacy, Church, and city. He was a man of great ego, ambition, and temper. He engaged in conflicts from all directions: religious, political, military, philosophy, and the arts. He used art and architecture as the primary means to satisfy his ambitions. He became a legendary patron of some of Western civilizations' most coveted works of art and architecture. He saw St. Peter's as a tool to reassert the authority of the Catholic Church and forever cement his name in the history books.

Interior photograph showing the central nave of St. Peter’s Basilica. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Initially, Julius hoped to renovate and add to the existing old St. Peter's. At the time, his primary interest was to have a tomb for himself sculpted by famed Renaissance artist Michelangelo and to house it within old St. Peter's. After designing the tomb, it was determined that the scale would not fit within the walls of the old Basilica.

Julius needed a larger building for his tomb. Hence, he dug up the plans for the Roman Basilica created by architect Bernardo Rosselino, commissioned by Nicholas V. It is difficult to tell whether these plans proposed renovating Constantine's existing structure or building a brand-new Basilica.

Julius brought architect Leone Battista Alberti to Rome to review the plans and walk the site. Alberti was a well-known architectural theorist from Florence. Alberti cautioned Julius against using any of the existing structures, as its walls were out of plumb, and the structural integrity was questionable.

Julius wanted another opinion, so he sent for Donato Bramante. Bramante suggested tearing down the old St. Peter's and building a new structure. Tearing down the original St. Peter's was an extremely contentious proposal. The Basilica had centuries of history within its walls, and Christians worldwide were worried about tearing it down.

Despite the criticism and rejections, Julius proceeded with the plans to demolish the old St. Peter's and build a completely new Basilica—one of massive scale, splendor, and notoriety that would surely cement his name in the history books.

Julius called for new design submissions for the Basilica. Giuliano da Sangallo and Donato Bramante. Sangallo's proposal fell short of the Pope's expectations. At the time, Bramante had only built one building. It was called Tempietto or the "Little Temple." The structure was modest, but the proportions were immaculate, simple, and captivating. Julius was captivated, and he felt that although the structure was small, it clearly illustrated Bramante's understanding of proportions and beauty. He felt his fundamentals were nearly flawless and translatable into a larger structure.

Because Julius was good friends with Sangallo, he tried to let him down easily. Ultimately, Julius decided that Bramante would be his architect for building the monument of New Rome.

Bramante had worked with Leonardo da Vinci in Milan for nearly twenty years. They closely studied Vitruvius's work on the fundamental principles of Roman Architecture. When Bramante moved to Rome, he spent years surveying and measuring Roman architecture to understand its proportions, materials, and structure.

In October 1505, Julius accepted Bramante's proposal for the new Basilica. The concept for the new Basilica was to be a Greek cross with a dome that rivaled the Roman Pantheon raised on the Basilica of Maxentius, one of the largest Basilicas built by the Romans. Achieving the size of both monuments was an enormous undertaking. The layout was a central plan in the shape of a Greek cross. The dome was to be raised on a large drum.

Unfortunately, many techniques the Romans used to construct these structures were lost. Bramante would need to recreate these techniques. He was credited with reviving the ancient techniques buried until that time.

The sculpture that had prompted Julius to build the new St. Peter's was now a second priority, and building the new Basilica was Julius' priority. Julius began dedicating all his funds to the Basilica, and there was little to nothing left for Michelangelo's work.

Bramante became the chief architect of all the Vatican's projects. He somehow undercut Jullius's favorites, Sangallo and Michelangelo. He created a circle of pupils, teaching them his techniques and philosophy. Many of his pupils would become the leading architects of subsequent generations in the Renaissance.

Construction of St. Peter's

Bramante evolved the design during construction, resulting in a design quite different from what Julius had initially approved. He met regularly with Julius to discuss the revisions and ask for additional funding to make the modifications. Julius watched the project closely and was notorious for signing off on the most minor details.

The funds required to pay for the construction were enormous, and in February 1507, Julius began asking for donations. In return for the donations, the Pope would grant indulgences or reduced sentences in purgatory. This highly controversial practice would later contribute to the Protestant Reformation.

Construction roared ahead, with an army of laborers, artisans, and skilled craftsmen on site every day. Rome was growing, and rebirth was happening. After years of dismal decay, Rome was beginning to emerge again as one of the cultural centers in Europe.

Julius was aging and understood that the end of his time was near. He pushed the artisans, sculptors, and architects to finish as much work as possible. Towards the end of his life, Julius had a heavy conscience and felt that "he had sinned greatly and had not bestirred himself for the good of the Church as he should have done." His contemporaries criticized him for bribery, misuse of power, misuse of funds, and warmongering.

Although much of this criticism is understandable, Julius also completely transformed a Church struggling to survive spiritually and financially. He had groomed and showcased some of the most notable artisans of the Renaissance: Bramante, Michelangelo, and Raphael. He saw their talents and allowed them to display their abilities. These artists created an identity for the Renaissance and changed Western culture's direction.

After Julius passed and new power was in place, Bramante's control of his commissions began to dissolve. Giuliano da Sangallo would eventually assume control over St. Peters. Bramante died in 1514, just one year after Julius.

When he passed, the four main crossing piers of the new Basilica were in place, and four arches spanned between them. It has been said that Bramante and Julius created the Basilica's skeleton and soul, and those who followed added the muscles and skin.

Interior photograph showing the central nave of St. Peter’s Basilica. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Michelangelo's Role

After Bramante's death, the project stalled. Several architects took over, including Raphael and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. However, Michelangelo made the most significant contributions to the Basilica's design.

In 1546, at age 71, Michelangelo was appointed chief architect of St. Peter's. He modified Bramante's original design, keeping the Greek cross plan but enlarging the dome and the supporting piers. Michelangelo's design called for a double-shelled dome, with an inner shell made of brick and an outer shell made of lead.

One of the most challenging aspects of the project was the dome construction. The dome is 42 meters in diameter and 138 meters high from the basilica floor to the top of the cross. It is the tallest dome in the world and one of the most iconic features of St. Peter's Basilica.

The construction of the dome began in 1588 and was completed in 1590. The inner shell of the dome was built using a technique called "centering," which involved creating a wooden framework to support the bricks until the mortar dried. The outer shell was made of lead plates, which were hoisted into place using pulleys and scaffolding.

The dome is supported by four piers, each 18 meters wide and 45 meters tall. The piers are decorated with niches containing statues of saints and angels.

Michelangelo worked on the project until he died in 1564, but he did not live to see the dome completed. His pupil, Giacomo della Porta, constructed the dome loosely following Michelangelo's designs.

Other Notable Features

In addition to the dome, St. Peter's Basilica is home to many other notable works of art and architecture. One of the most famous is Michelangelo's Pietà, a sculpture depicting Jesus on the lap of his mother, Mary, after the Crucifixion. The sculpture is in the first chapel on the right as one enters the Basilica.

Another notable feature is the baldachin, a large bronze canopy over the high altar designed by Bernini. The baldachin is 29 meters tall and is decorated with twisting columns and angels.

The Baldachin, a large bronze canopy over the high altar designed by Bernini in St. Peter’s Cathedral. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

The Baldachin, a large bronze canopy over the high altar designed by Bernini in St. Peter’s Cathedral. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

St. Peter's Square, located in front of the Basilica, is also a masterpiece of Baroque architecture. Designed by Bernini, the square is surrounded by colonnades that symbolize the arms of the Church embracing the world. At the center of the square is an ancient Egyptian obelisk brought to Rome in the 1st century.

Conclusion

The architectural history of St. Peter's Basilica is a testament to the genius and vision of some of the greatest artists and architects of the Renaissance era. From Bramante's original design to Michelangelo's modifications and Bernini's additions, the Basilica is a masterpiece of art and engineering.

Today, St. Peter's Basilica remains one of the most important pilgrimage sites for Catholics worldwide. It is also a popular tourist destination, attracting millions of visitors annually who marvel at its beauty and history.

I strongly recommend visiting and learning about the Basilica. Its role in the history of Rome, Christianity, and Europe is fascinating. I hope that you will find, as I have, that this seminal work of architecture can help formulate a more holistic understanding of our history and, thus, our contemporary world.

Check out our articles below to learn more about the story behind some of the world’s greatest buildings.

Bibliography

JENKINS, SIMON. Short History of Europe: From Pericles to Putin. PUBLIC AFFAIRS, 2021.

Miller, Keith. St. Peter’s. Harvard University Press, 2012.

Scotti, R. A. Basilica: The Splendor and the Scandal: Building St. Peter’s. Plume, 2007.

Statue in front St. Peter’s from St. Peter’s Square. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Front Facade of St. Peter’s from St. Peter’s Square. Statues of the 12 Apostles are located on top of the parapet. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Interior photograph showing the central nave of St. Peter’s Basilica. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

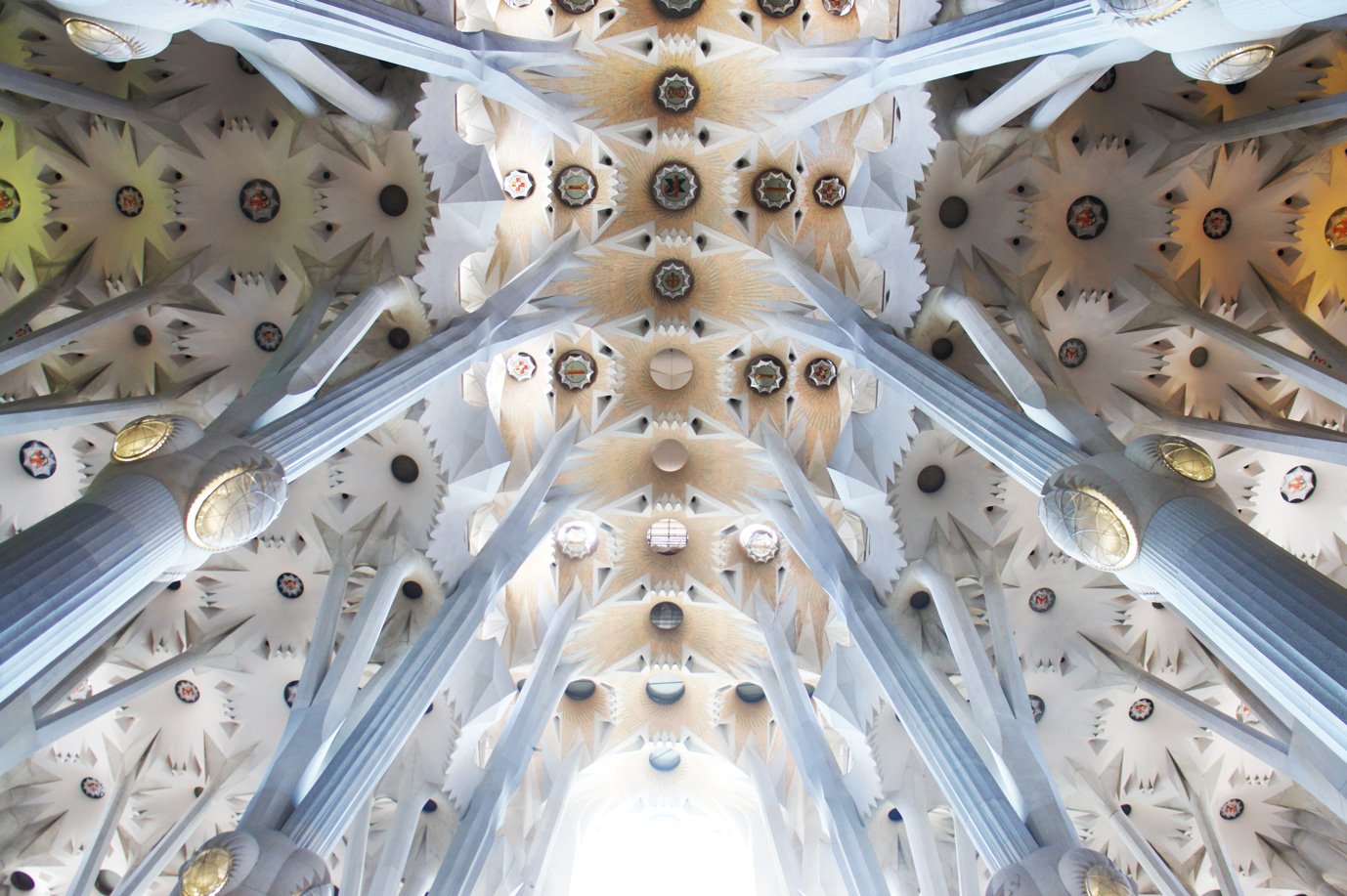

Interior photograph showing the ceiling coffering and vaulting of St. Peter’s Basilica. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Interior Dome of St. Peter’s Cathedral. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Interior photograph showing the central nave of St. Peter’s Basilica. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau