- The Tu family moved to San Leandro in 1960 despite its history of racism, and thrived; they helped make it one of America’s most racially diverse communities

David Tu and his family moved to San Leandro, in the US state of California, in 1960. Among the first Chinese to live there, his early years involved being bullied in school, harassed by police and taunted with racial slurs.

The census the year they moved in suggests why. Known informally as the “whitest city west of the Mississippi”, the settlement just across the bay from San Francisco was 99.7 per cent white, and city fathers were keen to keep it that way.

“Our city is not a ‘white spot’ by accident,” councilman Joseph Gancos declared proudly in 1969.

“It was not exactly an American heartwarming welcome,” says Tu, whose family arrived from Shanghai by way of Taiwan and Hong Kong without speaking English. “But five or six years later, we got our revenge when the Asian-Americans won all the scholarships.”

Said property shall not be used or occupied by any person whose blood is not entirely that of the Caucasian racePart of a 1938 real-estate covenant in a San Leandro estate

Tu and his four siblings would go on to become successful entrepreneurs, scholars and philanthropists and, in a dramatic transformation, San Leandro is now among America’s most racially diverse communities, with Asians accounting for more than a third of its 87,000 population – three times California’s average – as the white population has declined to just under 30 per cent.

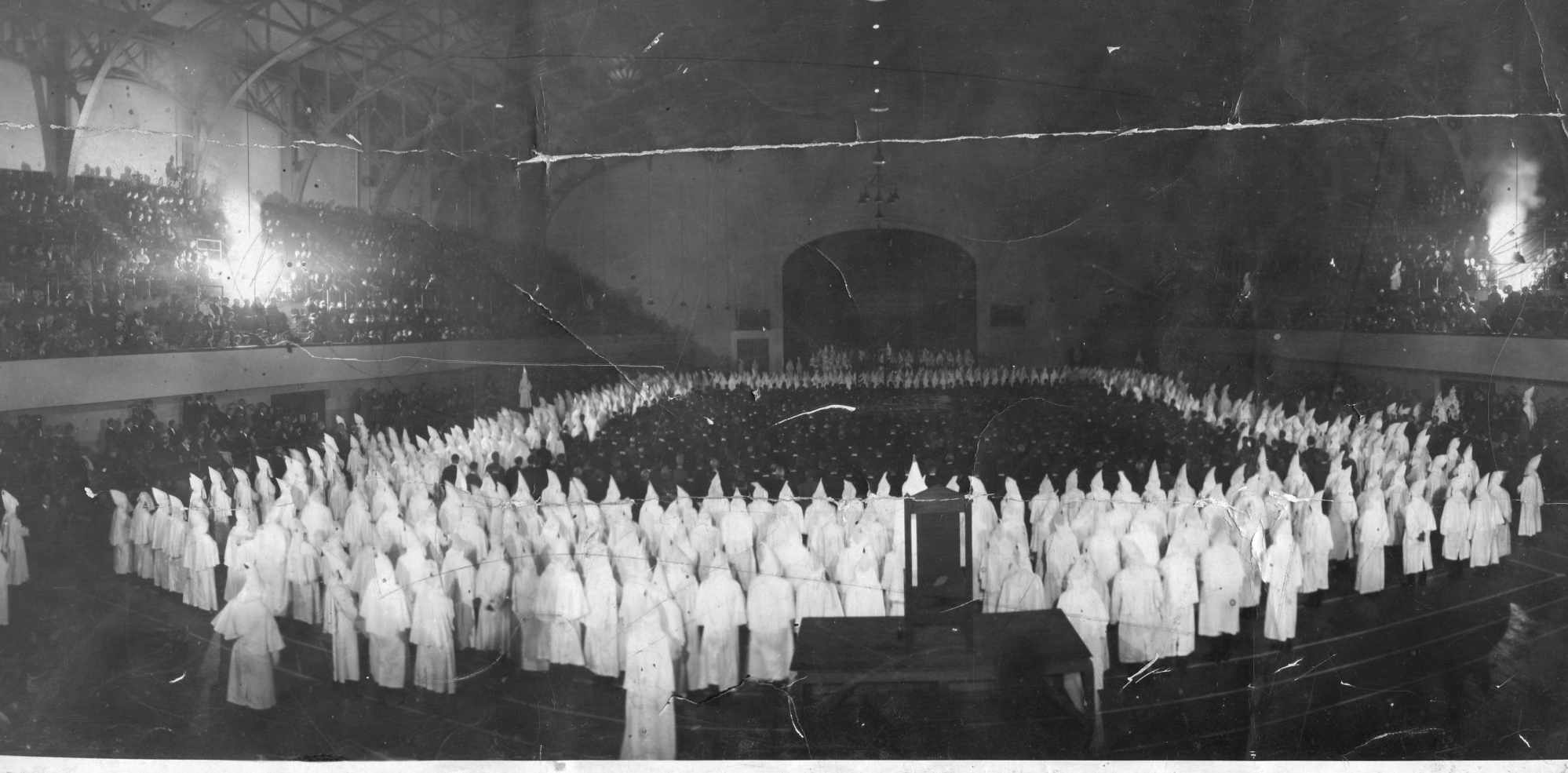

As the Tu family settled in, the primary tools San Leandro residents had drawn upon to preserve their city’s white-only status were intimidation, social pressure, discriminatory lending and racist real-estate covenants.

Although the United States Supreme Court ruled in 1948 that all racially restrictive covenants were unenforceable, their use continued, fuelled by prejudice and inertia.

But before that, a 1938 covenant in San Leandro’s upscale Bay-o-Vista estate read, “Said property shall not be used or occupied by any person whose blood is not entirely that of the Caucasian race, but persons not of the Caucasian race may be kept there by a Caucasian occupant, strictly in the capacity of servants.”

“All Welcome, Caucasians Only” was routine in San Leandro property listings in the early 1960s, recalls Ivan Cornelius, former president of the East Bay Association of Realtors.

In a 1970 version, the language became more opaque, although no less intention-laden, reading, “It is the purpose of Declarant […] to restrict the use and occupancy of said property to persons of a cultural status conducive to the creation and stimulation of congenial friendship.”

San Leandro was hardly unattractive to minorities. Rents were around half of those in San Francisco, and crime rates were a fraction of those in neighbouring Oakland.

This was despite what San Leandro’s then-mayor, Jack Maltester, argued in a 1971 television exposé, The Suburban Wall, suggesting minorities preferred to “live with their own kind”, saying “they wouldn’t move here away from their own neighbourhoods probably if you gave them a place for half price”.

Even that would not have mattered. Banks quietly refused to issue mortgages to minorities seeking homes in predominantly white neighbourhoods, initially marked in red ink on maps, a practice known as “redlining”, frustrating their path to middle-class prosperity.

Complicit property agents hid listings from people of colour, and San Leandro’s 10 or so major property developments, representing nearly two-thirds of homeowners, flexed their political muscle in the city council to block integration.

If all else failed, police and vigilante groups would arrest and harass minorities on specious charges.

If some people in San Leandro had their way, it would still be 99 per cent whiteDennis Evanosky, historian

And in a system known as a “sundown town”, maids and handymen from minority communities were allowed to work for white residents but faced violence if they remained after dark.

“Chinese, as well as African-Americans, didn’t belong, didn’t show up, weren’t wanted,” says Dennis Evanosky, a local historian and co-publisher of the Alameda Post. “If some people in San Leandro had their way, it would still be 99 per cent white.”

Incorporated in 1872, San Leandro emerged as a farming community famous for its fruit, its first “cherry queen” crowned in 1909. The 1910 census recorded two Filipino families, a single Japanese and a single Chinese out of 3,471 residents.

As late as 1970, San Leandro was still 97 per cent white, but the ground was starting to shift following passage of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act and the rise of black and Asian empowerment.

The city’s Asian population had reached 23 per cent by 2000, 29.7 per cent by 2010 and 34.9 per cent by 2023. The first Asian grocery store, Foodnet, opened in 1998, and by 2007 nearly half of new business applications were filed by Chinese immigrants.

Greater numbers also fuelled greater political awareness. A key turning point came in 2004, when a proposed crematorium in a heavily Asian neighbourhood was shelved after Chinese residents descended on City Hall, waking politicians to their growing clout.

Former San Leandro city council member Benny Lee credits long-time mayor and city councilman Anthony Santos for teaching the Asian community to organise, pushing for an Asian cultural centre and establishing “friendship city” ties with Yangchun, in Guangdong province in China.

Santos believed in the Asian community before it believed in itself, says Chinese-born Lee, who, despite a soaring Asian population, only made it onto the city council in 2012 – the first Asian to do so – a position he held until 2020.

Battles over affordable housing for migrants and minorities have raged for decades in San Leandro, racist graffiti defaced minority-owned businesses in 2016, and hate-filled leaflets scarred Asian-American neighbourhoods as recently as 2020.

“We consider you’re a stranger,” read a barely literate message left in a neighbourhood park. “Leave this country place no Asian allowed. My Country USA.”

The comfortable thing would’ve been to move to a Chinese enclave. But they made the choice, more for us, the next generationNorman Tu

Efforts to remove toxic language from covenants have also faced an uphill battle. Bay-O-Vista residents Kenneth Pon and Catharine Ralph campaigned to eradicate racist wording from subdivision documents. “It kind of eliminates that cloud over San Leandro,” says Pon.

Despite a 2022 California law requiring the state’s 58 counties to remove discriminatory language in all housing deeds, many remain. Hundreds of millions of record pages dating back to 1850 must be reviewed, many in handwritten ledgers, a task expected to take years.

“It’s not as easy to change as you think,” says Addie Silveira, curator emeritus of the San Leandro History Museum.

“Old rivalries and old lines of power remained entrenched,” noted a 2012 doctoral thesis on the white legacy of San Leandro, a city that bears a colonial Spanish name.

After months of debate and city council hearings, however, the city moved to tackle its racist history head on, leading to taped testimonials, personal remembrances and an acknowledgement that has been widely embraced.

“There was a level of caution that this could be a powder keg,” says Brian Simons, director of the San Leandro Public Library, “but little good has ever come, no matter what it is, of ignoring things. You just have to lean into it.”

The Tu family’s journey, and their part in San Leandro’s transition, was largely driven by their immigrant mother, Sieu Mei Tu, who died last July aged 96.

Initially struggling with English, the matriarch was determined to see her children assimilate, discouraging them from speaking Chinese at home so they could adapt to the white-majority world.

“The comfortable thing would’ve been to move to a Chinese enclave,” says Norman Tu, her oldest son. “But they made the choice, more for us, the next generation.”

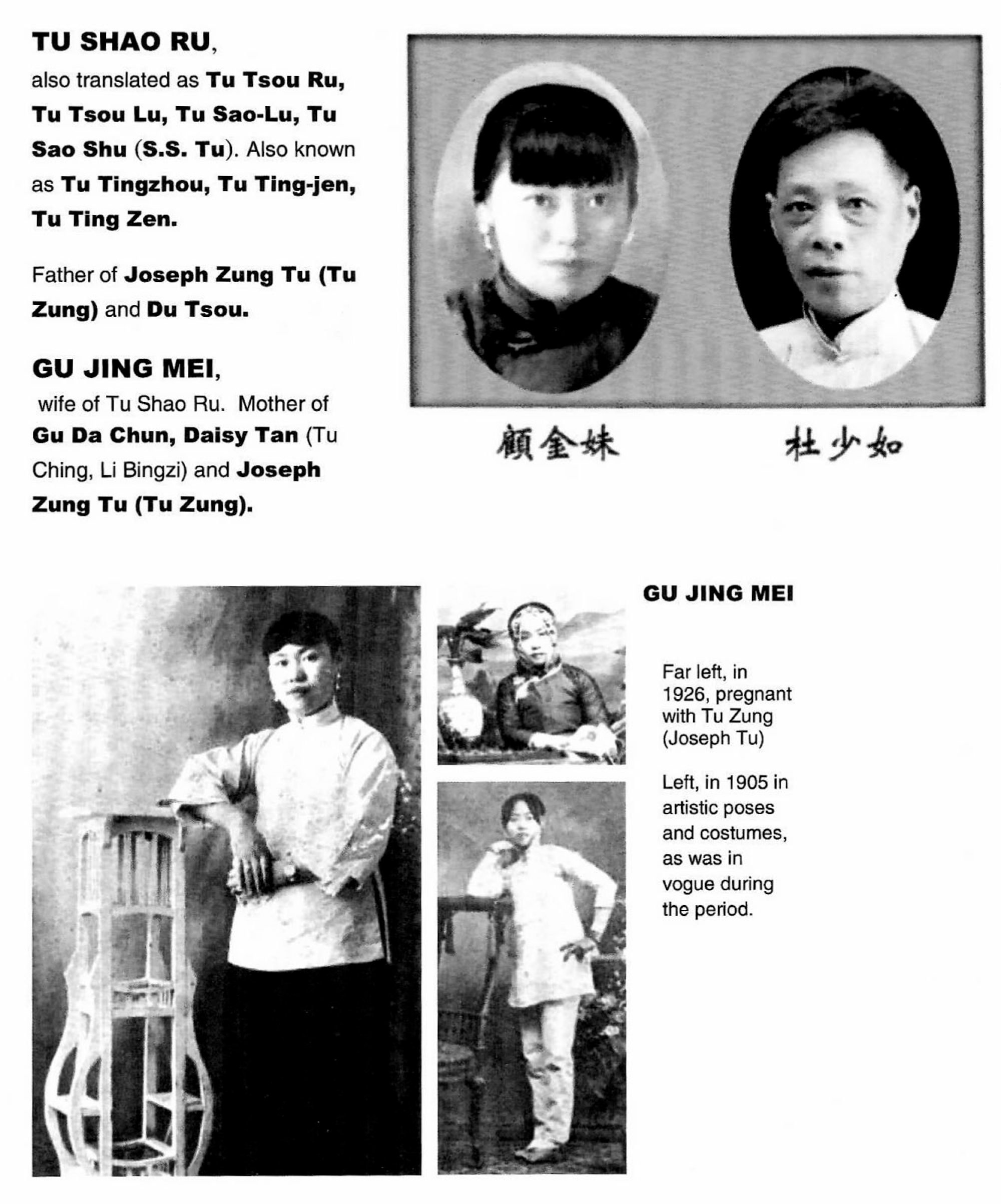

The Tus had come from a wealthy Shanghai family, their paternal grandfather, Tu Shao Ru, had been a 1920s industrialist who amassed a fortune in textiles, shipping, electric utilities and banking.

Most of the business empire and the Tu country home were located on Chongming Island, opposite Shanghai, where Tu Shao Ru built a hospital, roads, electric lines, schools and a training academy for sea captains.

Their family compound in the city, meanwhile, spanned blocks in Shanghai’s French Concession.

Patriarch Tu Shao Ru had seven wives, at least two cars including a Buick – a huge status symbol in those days – servants and bodyguards.

“I was playing with her feet, they were terrible. You can’t imagine how deformed they were,” recalls Elaine. “Only the very rich could do that because otherwise women needed to work in the fields.”

When the Japanese occupied Shanghai in 1937, business cratered, and by the 1940s, with war clouds brewing and the patriarch’s health failing, the family decided that the eldest son and heir apparent, Joseph Tu Zung, should marry.

Assembled matchmakers identified their mother, Sieu Mei, as a favourable match based on her social status and astrological readings.

There was one problem: both were born in the Year of the Tiger, and having two tigers in the same house was inauspicious. The matchmakers found a workaround, however.

Joseph had been born at noon, when tigers sleep, so he was deemed harmless, and their arranged marriage took place in April 1944. Grandpa Tu died a month or two later.

Dad was a classic Chinese father. He was no sweetheart. Whatever you do, you can’t get above waterDavid Tu

Sieu Mei was from a once-prosperous family with several successful restaurants in Shanghai’s British Concession. Since England was an avowed enemy of Japan, its Nazi allies and then-occupied France, their smaller fortune disappeared early on.

As a lower-status wife, Sieu Mei faced the meddlesome scrutiny of multiple mothers-in-law and sisters-in-law, maintaining a low profile and giving birth to Elaine, Norman, Ann and Harold in Shanghai and David in Taiwan between 1945 and 1951.

As the Communist Party consolidated its power, and with the family linked to the Nationalists, they decided in 1949 to leave, expecting it would be temporary. Joseph, on a business trip to Hong Kong, arranged for tickets, but the airport was soon closed and ships barred from taking civilians.

On her third try, Sieu Mei, 22, managed to find passage on a vessel to Guangdong after locating a captain who knew the Tu family, on the condition they hide below deck.

In a gut-wrenching decision, Sieu Mei and Joseph elected to leave one-year-old Ann and infant Harold behind. The latter got out a few years later with his grandmother, but they would not see Ann for another 15 years.

That left the problem of getting from Guangdong to Hong Kong. Perennially lucky, Sieu Mei met a stranger from Chongming who explained that a local general was visiting the area, and fate intervened: it turned out the general’s daughter was Sieu Mei’s sister-in-law.

Armed with this knowledge, she marched into the local headquarters exuding entitlement and pretended to be the general’s daughter, intimidating aides who approved their passage into British Hong Kong.

Unlike most rich families, the Tus were not despised by the Communists, having closed all their factories when the Japanese invaded and paid their workers relatively well.

The Communists still confiscated everything, and years later their father traded the substantial contents of a company safe in Hong Kong to keep the now state-run factories going, in return for Ann’s emigration.

It soon became clear the Communist revolution would last, and, given their Nationalist ties, Sieu Mei decided in 1951 to move the family to Taiwan.

David was born in Taipei, and Elaine recalls playing with her émigré cousins while living in a Japanese house with tatami floors her father soon ripped up. “He wanted to walk in the house with his shoes,” she says.

Only about 100 Chinese were allowed in annually, and those were required to show employment prospects, a home, their opposition to Communism and a family sponsor.

Those odds were tough enough. Their father, Joseph, who was not in good health, was required to take a urine test. Years later, David asked his mother how he had passed the physical. “I don’t know if it was your dad’s urine,” she had said sheepishly.

When in the light, I’d head for the darkness. I tried to be like the cockroach, but generally I got beat up pretty badDavid Tu

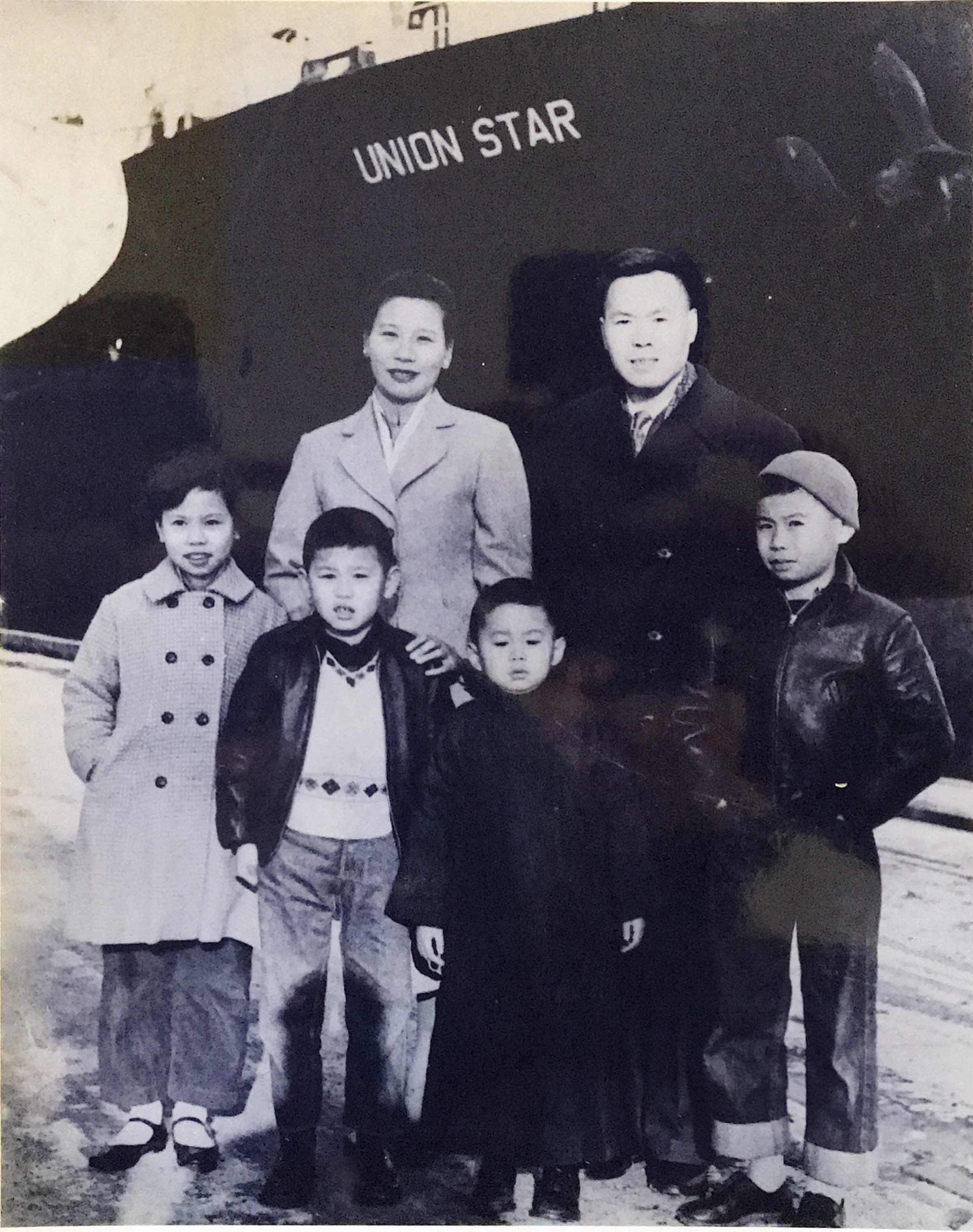

After nearly six years in Taiwan, their savings largely depleted, the US visas finally came through and in 1956 they sailed to North America aboard the Union Star freighter, all six packed into a single cabin, miserably seasick, disembarking on December 7.

The two families lived in a duplex, with the Tus inhabiting the smaller flat upstairs.

Though the Tu family is enormously grateful that the Tans took them in, there were some inevitable tensions. Elaine recalls not being allowed to watch the Tans’ television inside the house, instead viewing it through the window from the street.

The first several years were tough, financially, linguistically and culturally. Sieu Mei, a devout Christian, met members of the Mormon and Baptist churches, who hired her to clean their houses for US$1 an hour.

She traded English lessons for the children in return for washing cars and, later, they tried to help with the legalities required to get Ann out of China.

Raised in luxury and fully expecting to inherit the family fortune – “spoiled and entitled” in David’s words – their father never fully adjusted to his new life working on an assembly line, as a cook and a mailroom worker.

The children lived in fear of him, never daring to contradict him, financial insecurity never far away.

“Dad was a classic Chinese father. He was no sweetheart,” says David. “Whatever you do, you can’t get above water.”

Thrown into the public education system, the children were the first Asians to attend their San Leandro schools. Harold and David were younger and picked up English quickly. Norman struggled and retreated into maths and science. Elaine was the model student.

In 1960, the Tans moved to more upscale Hayward, prompting the family to buy a basic 1,100 sq ft (102 square metre) house in Bonaire, a working-class Portuguese neighbourhood. The three boys slept in one room, Elaine in another, the parents in the third.

The children were always under pressure to study, only permitted to watch television news for a few hours on weekends.

I love going to reunions. We introduced ourselves counterclockwise. He said, ‘I’m a plumber,’ and I said, ‘I hire plumbers.’David Tu on running into one of his former tormentors

Elaine recalls watching The Ed Sullivan Show, a popular variety programme, and hearing The Beatles and Elvis Presley through friends. “The children, not the adults, were crazy about them.”

Unaware of any exclusionary covenants governing sales in the subdivision, Elaine did recall neighbours voting to accept them.

To finance the US$17,000 price of the property, the Tus cobbled together three mortgages. Decades later, Joseph and Sieu Mei would die in the house, at their own insistence.

“I think we were Asian zero,” says David. “We just stood out.”

He recalls classmates trying to stuff him into a school locker in junior high, and “the only reason I didn’t get stuck in there was my head didn’t fit”, he says, adding that he spent years trying to avoid attention.

“When in the light, I’d head for the darkness. I tried to be like the cockroach, but generally I got beat up pretty bad.”

Years later, by then earning a good salary working for a Bay Area property developer, David attended a high-school reunion where he ran into one of his old tormentors.

“I love going to reunions,” says David. “We introduced ourselves counterclockwise. He said, ‘I’m a plumber,’ and I said, ‘I hire plumbers.’

“I’m not above this,” he says with a laugh.

David remembers how, after he had graduated from high school, he was going to pick up Elaine from her late shift at a pizza parlour when a white policeman stopped him on an overpass.

“What are you doing here?” the officer said. “I don’t ever want to see you on this street again.”

For months, David took a detour to avoid another run-in. If he were the type to have succumbed to racist rage, David says it would have developed in those years, though in retrospect, it motivated him to prove the racists wrong.

“It’s one one-thousandth of what black people face,” he says. “But it was disconcerting. It’s my home.”

They’d say, ‘Ching chong Chinaman. Won’t you go back, you don’t belong. Chop suey’. Those mean things are very hurtful, especially at that ageNorman Tu

Harold was also bullied and almost got kicked out of school. Struggling against stereotyping, racial profiling and ridicule, he adopted a more strategic alliance: “This little short Jewish kid and the little short Chinese kid – you could make a comedy of it,” he says.

Harold convinced his new ally to be his campaign manager and ran for president of the student body with the slogan: “A vote for Tu is a vote for you.”

Taken aback when he won, Harold bonded with other victims and put the bully on the defensive.

“I reused that template throughout my career,” says Harold, who has broken glass ceilings and fought prejudice as a surgeon, dentist and department head at the mostly white University of Nebraska Omaha. “I realised I could either view my difference as a negative or turn it into a positive.”

Norman, meanwhile, was fast and athletic, played basketball and broke several track and field records. But their parents, obsessed with academics, never attended a single game, refusing to sign the release form when he was recruited to play football.

Athleticism brought a measure of respect. But it did not spare him from bullying, which Norman ascribes more to ignorance than malice. Most classmates had never met an Asian.

Elaine faced no prejudice growing up. “I had three strong brothers to protect me!” she jokes.

On the rare occasions when they complained to their mother, they got little sympathy. “Basically we were racist against others,” says David. “She would say, ‘They’re all barbarians, don’t fret, they haven’t come down from the trees yet.’”

Ann, who finally arrived as a teenager in 1964 with help from the Red Cross, faced her own tough transition before finding her feet, earning two bachelor’s degrees and forging a career in the food and tech sectors.

Although money was tight growing up, higher education was never in question. Driven by their mother, who was forced to leave before finishing high school, all the children graduated college, drawing on scholarships, summer jobs and whatever their parents could provide.

After a rigid, traditional home environment, the boys went a bit wild when the shackles were removed. Their parents were ecstatic when Norman got into the prestigious University of California, Berkeley, then refused to acknowledge it when he flunked out, in part because of his still-weak English but also from partying too much.

Weighed down by his parents’ expectations after they had sacrificed so much, he hit rock bottom.

“They made it worse by shaming me,” says Norman, an approach he has tried to avoid with his own children. “I felt like a complete failure.”

She’s brilliant. It’s tough to know a family member like thatNorman Tu on their cousin, author Amy Tan

After several months alone in a cheap, gritty flat, he regrouped and entered California’s Chico State, graduating with a computer-science degree in 1969.

Harold, who also got into UC Berkeley, soon fell into “sloven drunkenness, wine, women and song. It was an opportunity for complete freedom”, he says. “I didn’t take that responsibility very well.”

He developed an ulcer and transferred to the far less prestigious Linfield College, in Oregon, and hit the books, ultimately becoming a prominent member of the medical community and campaigner against opioid addiction.

David got into the University of California, Davis, and, taken with the social and cultural ferment of the 1960s, recalls joining anti-war protests then switching into “proper” clothes before returning home to see his parents.

After his grades slipped, he also regrouped, joining the prestigious Lawrence Livermore lab.

After graduation, tech-oriented Norman worked for Xerox and Hewlett-Packard before starting DisCopyLabs in 1982, with his wife, Antonia, copying software onto floppy discs.

Norman recalls how in 1985 he asked his cousin Amy Tan, before she became famous, to write a technical brochure. It came back so well written that it sounded like a different company. “Wow, we do all this?” he said. “She’s brilliant. It’s tough to know a family member like that.”

After two years at Lawrence Livermore lab, David hit a kind of Asian glass ceiling, and became a regional property developer before joining Norman in 1987 at DisCopyLabs, subsequently renamed DCL, where he rose to become president. Both are now retired and the next generation of Tus has taken over active management.

Elaine, meanwhile, studied biochemistry and nutritional science at UC Berkeley, conducted research for Nasa, and took up a fellowship in Germany. There she met and married a German doctor – the union resisted by both families before their children came along – and the couple worked together for 20 years.

Sieu Mei, having transformed a family and helped transform a city, was survived by 11 grandchildren and 18 great-grandchildren at her death last summer, 13 years after their father.

As the family grew wealthy, it contributed to numerous charities related to education, Chinese-American history, legal aid, and to an endowment in honour of Sieu Mei at the University of Nebraska.

As David puts it, “We stand on her shoulders.”