The battlegrounds that could decide a US-China war over Taiwan

Five key military contests are likely to determine the outcome of a conflict

General Douglas MacArthur, the US commander during the Korean War, once called it the “unsinkable aircraft carrier”. Taiwan, a mountainous country roughly 180km from China’s coast, occupies a strategically vital position for both China and the US.

For Beijing, Taiwan and its islands are part of its territory, which it wants to unify with the mainland and in the process push US military power ever further away from eastern Asia.

Since the January election of pro-independence Lai Ching-te as Taiwan’s next president, China has continued to use coercive tactics to intimidate Taipei, such as entering its air defence identification zone (ADIZ).

In the run-up to Lai’s inauguration on May 20, Beijing has been flying its military aircraft closer to Taiwan, while its navy vessels have frequently skirted Taiwanese waters.

If China were to gain control over Taiwan, it would break through the first island chain — a string of US-friendly islands in the western Pacific that form a natural barrier to Chinese expansion.

The second island chain, stretching from the Japanese islands to the US territory of Guam and the islands of Micronesia, acts as a further buffer.

Three decades of investment means China’s military is now close to being able to fight a Taiwan war. In response, the US military is devising new warfighting strategies and strengthening military alliances.

The Financial Times has identified five key military contests that would help define the outcome of a war. Few analysts or officials believe a conflict is imminent, but any clash between the world’s top two powers would have global consequences, triggering the biggest international crisis since the second world war.

‘It’s all about the missiles’

Once mocked by its own troops for having “short arms and slow legs”, China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has spent decades transforming itself into a world-class fighting force.

At the heart of this modernisation has been the country’s investment in missiles in a bid to close the gap with the US. “It’s all about missiles,” says Eric Heginbotham, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology security expert and co-author of a Taiwan war game.

The PLA’s Rocket Force has big arsenals of short, medium and intermediate range ballistic missiles, which can sink US aircraft carriers and deny its military the opportunity to dominate the region’s air and sea.

China’s Rocket Force bases are spread across the country, making it very risky for the US Air Force to fly in the Taiwan Strait during wartime.

American air and naval assets on US bases in Japan, South Korea and Guam are also vulnerable to China’s longer-range weapons.

To reach Chinese targets, the US could deploy ground-launched, precision-strike missiles, with a range over 500km, to Japan or the Philippines if those governments agreed.

While the US has its own bases in Japan, it has to request permission to access bases in the Philippines — its only other ally close to China.

The US Army’s Dark Eagle hypersonic weapon, being deployed to Guam this summer, would be able to hit Chinese positions from US soil given its 3,000km range.

Taiwan has also built up its missile capabilities. It now has domestically developed missiles with ranges of up to 2,000km and it has set an ambitious target of producing 1,000 missiles in 2024.

Japan has also expanded its arsenal. As well as US Patriot surface-to-air missiles, its islands will host Type-12 anti-ship missiles, with a range of 200km. Tomahawks, which can be launched from the ground or sea, are expected to be delivered in 2025.

China’s growing array of missiles have a clear goal: making it increasingly hard for the US to assert its traditional strengths of air and naval dominance.

In both Gulf wars, as well as in Kosovo, the ability of the US to build up forces near an adversary’s territory at little risk of being hit by enemy fire was a decisive advantage, says Jacob Heim, a researcher at the RAND Corporation think-tank in Washington. But Heim says that strategy would be ineffectual against China. “That legacy way of war wouldn’t work against the PLA with its missile arsenal.”

One of China’s newest medium-range missiles is the Dongfeng-17. Its warhead can manoeuvre at hypersonic speed — five times the speed of sound, or faster — making it hard for missile defence systems to detect. The Dongfeng-26, nicknamed “Guam Express” because of its ability to hit US Pacific island territories, such as Guam, is another key missile. Its anti-ship variant is known as the “carrier killer”.

[]

[]

In different scenarios in a war game co-developed by Heginbotham for the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a Washington think-tank, the PLA’s invasion of Taiwan failed, but the US lost between 168 and 372 aircraft on carriers and at air bases.

The US would therefore face the complex challenge of reducing the vulnerability of its forces while also trying to get close enough to sink China’s invasion fleet.

A US military official suggests one tactic could be to lure China into using a large number of missiles before the US launches a counter-attack with stealth bombers — a way to attack China hard and fast.

“Air-launched missiles remain a much more efficient way of hitting a large number of targets compared to China’s much larger ground-launched missiles,” he says. “We can fit 20 to 24 on each bomber, so if you get 10 bombers in the air — that’s 240 missiles incoming.”

But others caution that speed is of the essence and that delayed US strikes could allow a PLA invasion force to gain an irreversible foothold.

Small islands and narrow straits

While Beijing has upset America’s traditional way of fighting with its high-tech missile arsenal, US forces are countering by changing the way they use one of the oldest features of war: geography.

As well as strengthening missile defences in Guam, the US is working with allies to disperse its forces. That makes troops, aircraft and weapons harder to track and multiplies the targets the PLA has to hit.

The US Air Force plans to move groups of aircraft from their main bases in Japan to small, austere airfields for short periods. The navy has a strategy that follows a similar logic.

The Marine Corps is also rehearsing moving small units to remote islands or coastal jungles in the region. From there, they would support other services using reconnaissance and communications systems that emit fewer electronic signals, making them difficult to detect.

Their other mission would be to put Chinese naval vessels at risk with short, medium and long-range coastal defence missiles.

PLA navy ships would have to pass through the narrow Miyako Strait or Bashi Channel to enforce a naval blockade, but that would make them easy targets for missiles deployed on the first island chain.

In joint exercises this year and last, US and Philippine troops simulated retaking islands in the Philippines’ northernmost territory of Luzon. They also practised sinking ships with coastal defence missiles.

China responded furiously to Manila’s decision last year to grant US forces access to four more Philippine military bases, including three in the far north.

The small islands south-west of Okinawa would also be “ideal locations” for targeting PLA forces, said a person familiar with discussions between the US and Japan.

One of the key reasons this is possible is the demise of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), which barred the US from developing ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles between the ranges of 500 and 5,500km, before both the US and Russia withdrew in 2019.

The US army will put ground-based missiles, including Tomahawks and short range SM-6, in the region from this year and may add precision missiles later, its commander Charles Flynn announced in November 2023, a move Chinese Communist party media called a “provocation”.

While US forces are expected to retain use of their bases in Japan in a Taiwan conflict, the politics of whether it can use bases in the Philippines is a lot less clear-cut.

As part of the recent exercises in the Philippines, the US brought the Typhon, a system capable of launching Tomahawks and SM-6, to northern Luzon in the first such deployment in the Indo-Pacific since the collapse of the INF treaty.

While no US ally has expressed willingness to permanently host US ground-launched missiles, they are boosting their own capabilities. Japan has ordered 400 Tomahawks from the US, and the Philippines is getting BrahMos, Indian-Russian made supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles. Taiwan has purchased 29 US Himars rocket launchers, which can also be mounted on to trucks.

[]

[]

Japan has been upping its defence presence on its remote southwestern islands in other ways, deploying new military units and expanding its bases. New bases have been established on Ishigaki and Miyako, where a former golf course is now a functioning military facility.

Miyakojima base, Japan

Chiyoda golf course on Miyako Island was recently converted into a missile base

The stealth weapon

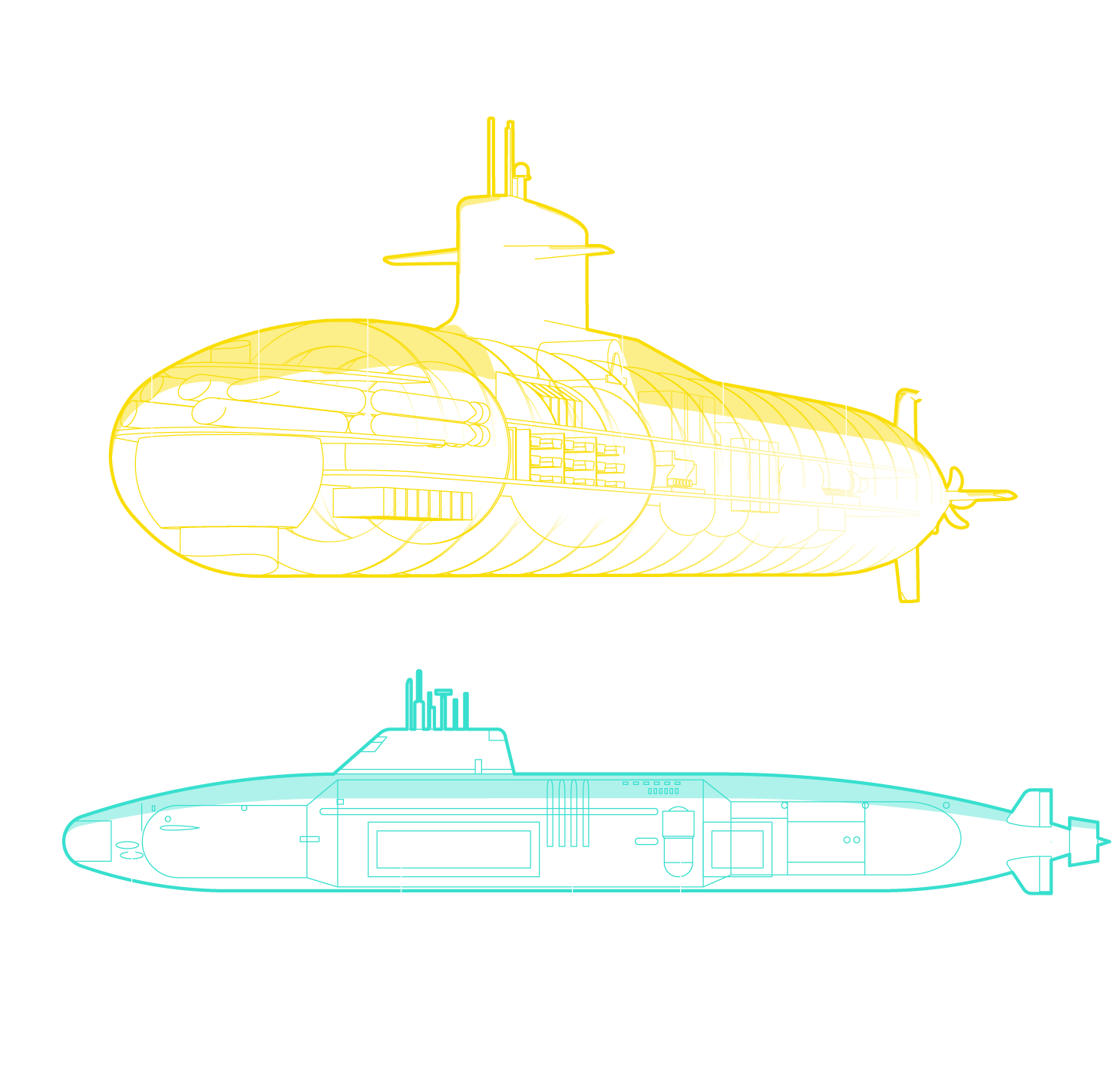

The single most potent capability the US military can leverage close to Taiwan is its strong submarine force. Hard to detect and therefore mostly immune to anti-ship missiles, American nuclear-powered submarines could get close enough to target Chinese ships and planes in the Taiwan Strait.

But Washington’s advantage is being eroded. The large technological gap between China and the US in undersea warfare “is shrinking”, Sarah Kirchberger, a Chinese military expert at Kiel University, told the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission in April 2023.

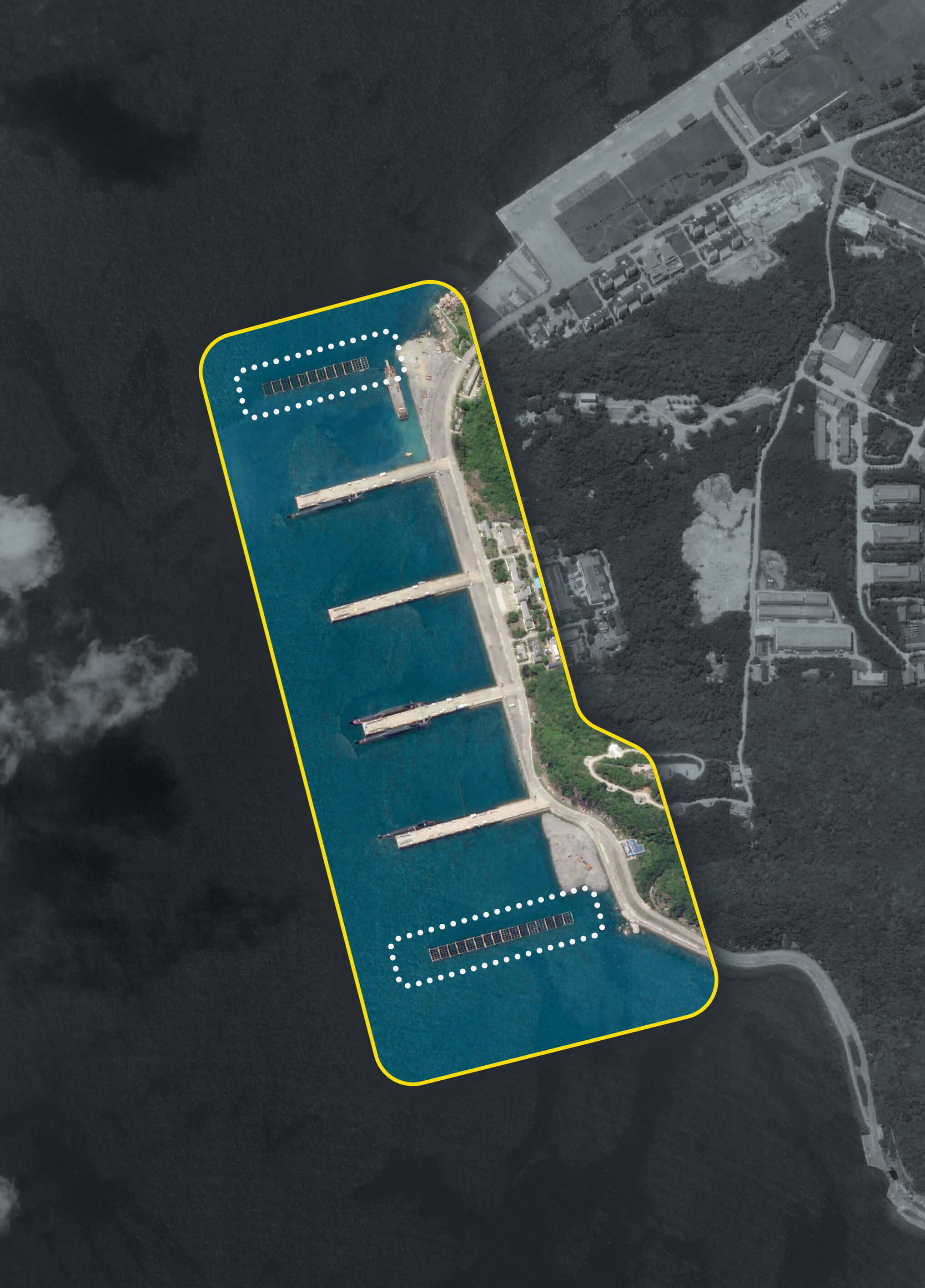

In January 2023, China launched its first nuclear-powered attack submarine with a pump jet propulsor — a technology enabling higher speeds with less noise. It has also expanded its submarine capacity. At Yulin Naval Base on China’s Hainan Island, two new piers have been added within the past few years.

Yulin Naval Base, China

Extra submarine piers were added to the Hainan Island base between 2021 and 2024

In one effort to work with allies to counter China in the longer term, the US in 2021 signed Aukus — a security pact with Australia and the UK that will enable Canberra to procure nuclear-powered submarines. While the new vessels will not be ready until the early 2040s, US deputy secretary of state Kurt Campbell recently said having a number of countries operating submarines in close coordination would have “enormous implications” for scenarios that included Taiwan. To bridge the two-decade gap, the US will sell as many as five Virginia-class submarines to Australia from 2032.

But the key question will be how the US builds up its own submarine force in the coming years.

“How much of a lead the US would have in wartime therefore depends on when you assume that conflict [over Taiwan] takes place,” says a US navy officer.

The PLA navy has also been making heavy investments in anti-submarine warfare (ASW). “America’s and Japan’s nightmare is about to come true!” state broadcaster China Central Television said in 2017 in a report about plans to deploy a network of undersea listening devices to spot an adversary’s submarines, inspired by similar installations the US used during the cold war.

The hydrophone systems will now likely be set up in a number of locations including the East China Sea, the South China Sea and in the vicinity of Guam, home to the US’s main submarine base in the Pacific.

Over the past decade, China has also equipped dozens of surface ships with advanced sonar systems and acquired a growing number of patrol aircraft and helicopters with ASW gear. This will allow the PLA to use the same narrow straits that constrain its own navy to put US submarines at risk. In its almost daily air and naval operations close to Taiwan, one of the PLA’s most frequent activities is ASW manoeuvres.

“[China is] very focused on collecting data on the seafloor and subsea environment . . . which is vital for their submarine and ASW operations,” says Su Tzu-yun, an analyst at the Institute for National Defence and Security Studies, the Taiwan defence ministry’s think-tank.

The battle for space

Satellites and other space-based capabilities are critical components of modern warfare. Militaries use them for a range of purposes, from surveillance and weapons guidance to warning of incoming attacks.

The PLA has dramatically boosted the number of satellites it has for communications and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) operations in recent years.

Major General Gregory Gagnon, the top intelligence officer at US Space Force, has said China is expanding so rapidly that the US no longer has a “monopoly” on using space for ISR.

“The breakout pace in space is profound,” Gagnon said at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

In March, General Chance Saltzman, US chief of space operations, said China had deployed over 470 ISR satellites as part of a “sensor-shooter kill web” that threatens US forces around the world.

The US is also worried about China’s ability to destroy American satellites. The Pentagon is responding by significantly increasing the numbers of sensors it deploys to monitor Chinese satellites.

The US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) has warned that China is building sophisticated cyber weapons to seize control of enemy satellites in wartime. In 2022, a Chinese satellite grabbed another satellite and moved it off orbit, in a manoeuvre that showed its advances in space.

The Pentagon says China is also developing electronic warfare systems and directed-energy weapons, such as lasers, that could be used to deny the US access in space. Chinese published research and reports about modern warfare techniques suggest that disrupting US information systems used in the field would be a priority.

“We need to ensure that we have some resiliency so that we can continue to operate [in space] even though those systems will be under persistent PLA attack,” says Jack Bianchi, an analyst at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, a Washington think-tank.

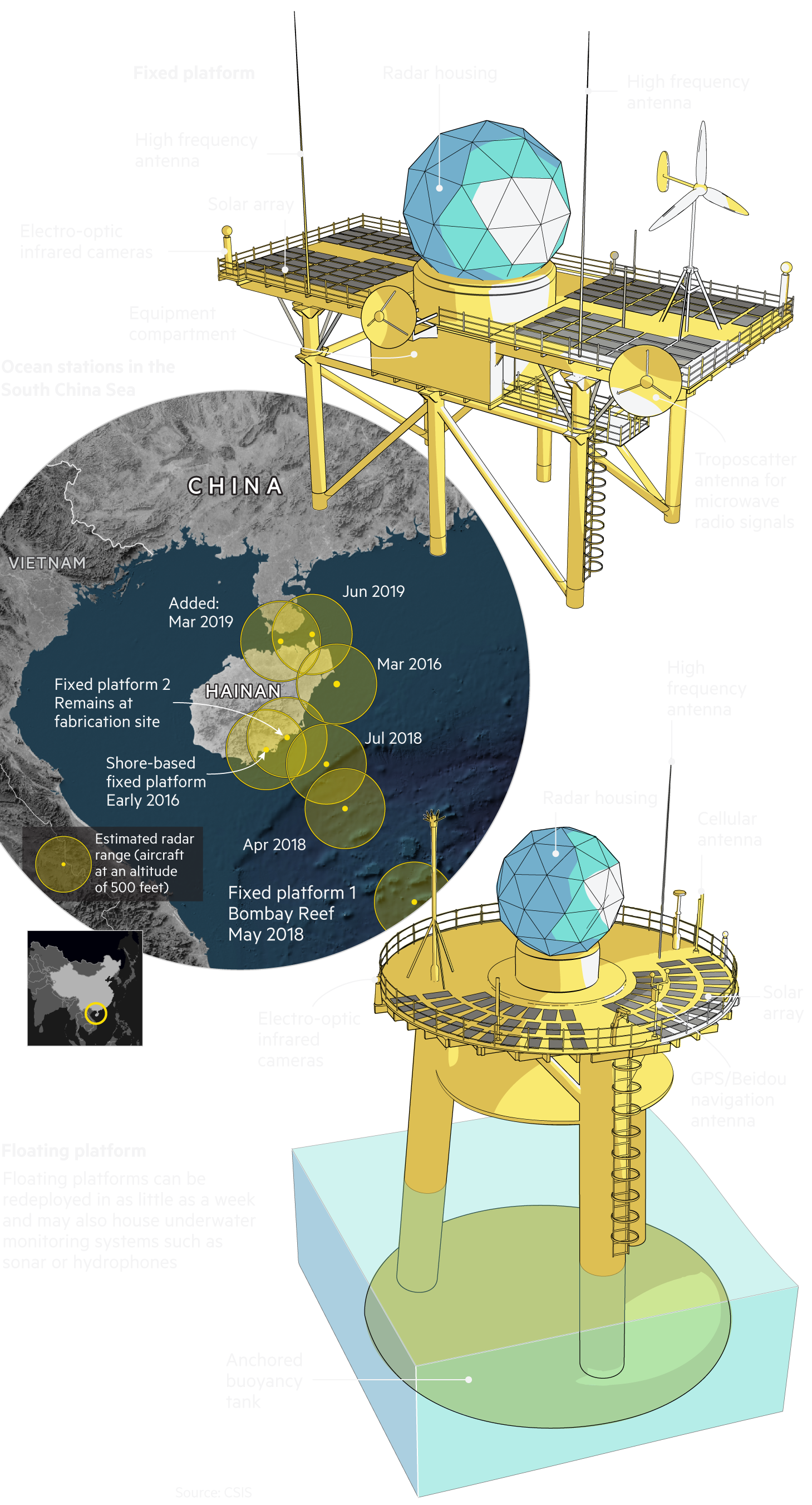

The Chinese military is also focused on building its own resilient communications networks. Between 2016 and 2019, state-owned defence contractor China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC) built a smattering of fixed and floating platforms studded with sensors and transmission devices in the northern part of the South China Sea, between the Paracel Islands and Hainan, where its main submarine base is located.

China’s ocean communication stations

While the US has raised concerns about Chinese proficiency, the full range of American assets and capabilities in space remains unknown.

The US will require robust communication systems to link its military units given its plans to disperse them across the region, military analysts say.

Destroying or at least disrupting Chinese space-based military communication would be critical for Taiwan’s fight on the ground. The country’s dense urban and mountainous terrain no longer offers its troops an advantage, says Jack Watling, a land warfare specialist at the UK military think-tank Royal United Services Institute, who has been observing the battle on the ground in Ukraine.

“If your adversary has sensor dominance, they will find you in that terrain,” he says. “And so a critical question is: are you able to deny and degrade their sensor capability? That means disrupting space-based observation and reducing the efficiency of enemy reconnaissance. That is the persistent message from Ukraine.”

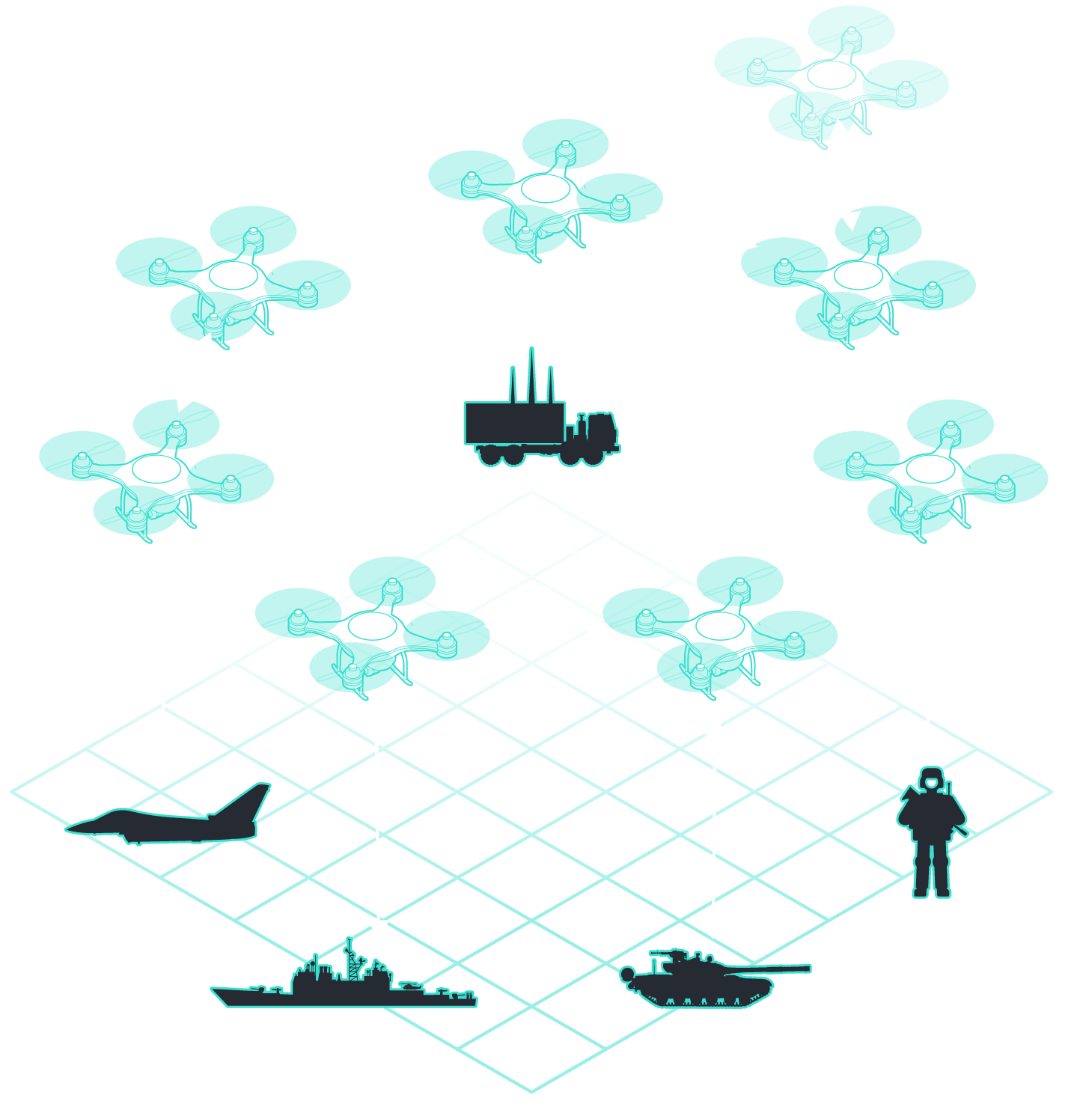

If an initial Chinese attack destroys Taiwan’s communications networks, troops will need a way to communicate if they are to find and target China’s forces. One solution under discussion is creating a “sensing mesh” in the Taiwan Strait with swarms of small, unmanned aerial vehicles. This will enable ground troops to locate the invaders with coastal defences, or weapons like Stinger and Javelin missiles.

Drone mesh network

The greatest fear

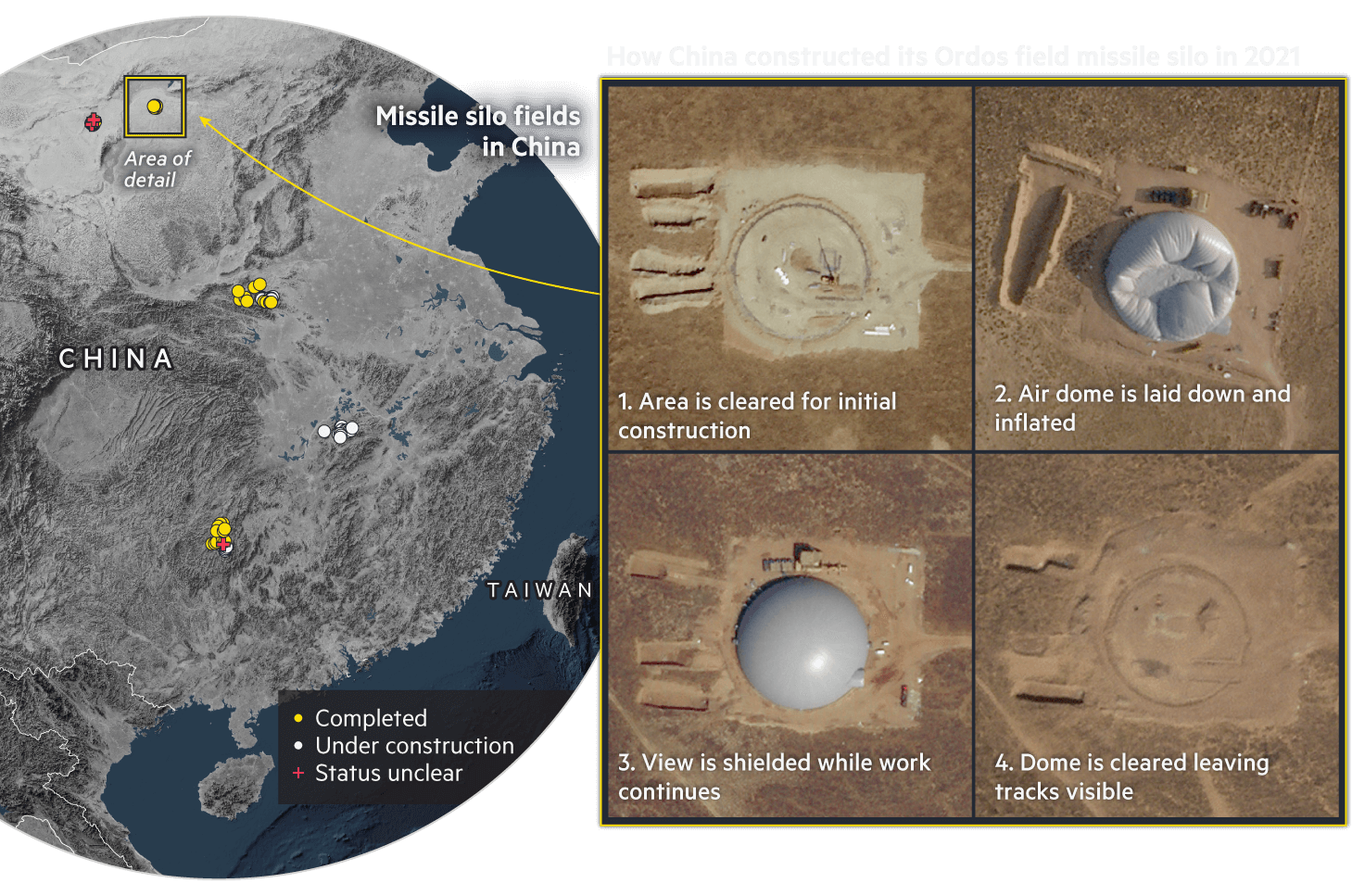

One chilling question about a conflict between the US and China over Taiwan is the role that nuclear weapons could play. China for years had a relatively small arsenal that it described as a “lean and effective” nuclear force, but it has been rapidly expanded in recent years — with no explanation given.

In 2019, General Robert Ashley, head of the US Defense Intelligence Agency, said China’s total nuclear warheads were in the low 200s and would double over the next decade. But last year the Pentagon said China had increased this to 500 and was on course to have 1,500 by 2035, roughly matching the number of strategic warheads the US has deployed under the cap imposed by arms control agreements with Russia.

China has also developed a nuclear “triad”, enabling it to deliver nuclear warheads from land, air and sea. Its submarines can now strike parts of the US mainland from waters close to the Chinese coast, where the vessels are less vulnerable.

The expansion of China’s arsenal raises two critical questions about the potential role of nuclear weapons in a conflict. Could the US still use its nuclear missiles to deter China from attacking Taiwan? Or is it more likely that they would help Beijing deter Washington from intervening?

Either way, the combination of the surge in China’s warheads and more varied delivery systems means the US has to pay greater attention to the possible nuclear dimensions of a conflict.

Greg Weaver, a nuclear weapons expert who served on the Pentagon’s joint staff, says the changes in China have big implications for whether the US could destroy Chinese nuclear forces if a fight over Taiwan was going badly for the US. Weaver says a key issue for the US is: “Is our stake in Taiwan high enough to risk nuclear war with China?”

“There is a significant difference in the difficulty of taking out a force of 500 warheads than there is for 200,” Weaver adds.

China continues to develop missile silo fields

There are many permutations for how Washington and Beijing could use nuclear weapons in a Taiwan conflict. This could include limited strikes in the theatre or threatening to strike mainland China or the US in order to convince the other to back off.

The US could target Chinese ships that are trying to conduct an amphibious landing on Taiwan. China could use the threat of nuclear weapons to pressure US allies who provide critical logistical support, including access to bases.

Some defence experts are concerned that because Washington does not enjoy a conventional military advantage over China in its backyard, it raises the spectre of the US deciding that nuclear weapons would give it the edge.

“What worries me is that the US could consider limited nuclear use because it cannot bring enough bullets to the fight,” says Taylor Fravel, an expert on the Chinese military at MIT. “If you cannot match China ship for ship, you can sink 10 ships with one nuclear weapon.”

Air defence identification zone violations according to Taiwan’s Ministry of Defense. Missile capabilities according to the Pentagon, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Taiwan’s Ministry of Defense and Japan’s Ministry of Defense. Additional information on Taiwan from Masao Dahlgren of the CSIS. US military bases according to the US Congressional Research Service, the Pentagon and the US military. China’s Rocket Force bases according to the Pentagon and the China Aerospace Studies Institute.