- India

- International

Was the Stone Age actually the Age of Wood?

Wood from the Stone Age rarely survives in the archaeological record. But a recent study suggests that wooden tools played a pivotal role in the daily lives of early humans

A signpost in Schöningen, Germany designed by Peter Tuma to guide people to the museum displaying Schöningen Spears . (Wikimedia Commons)

A signpost in Schöningen, Germany designed by Peter Tuma to guide people to the museum displaying Schöningen Spears . (Wikimedia Commons)New research indicates that the Stone Age — a long prehistoric period characterised by the use of stone tools by humans and our ancestors — might as accurately be described as the ‘Wood Age’.

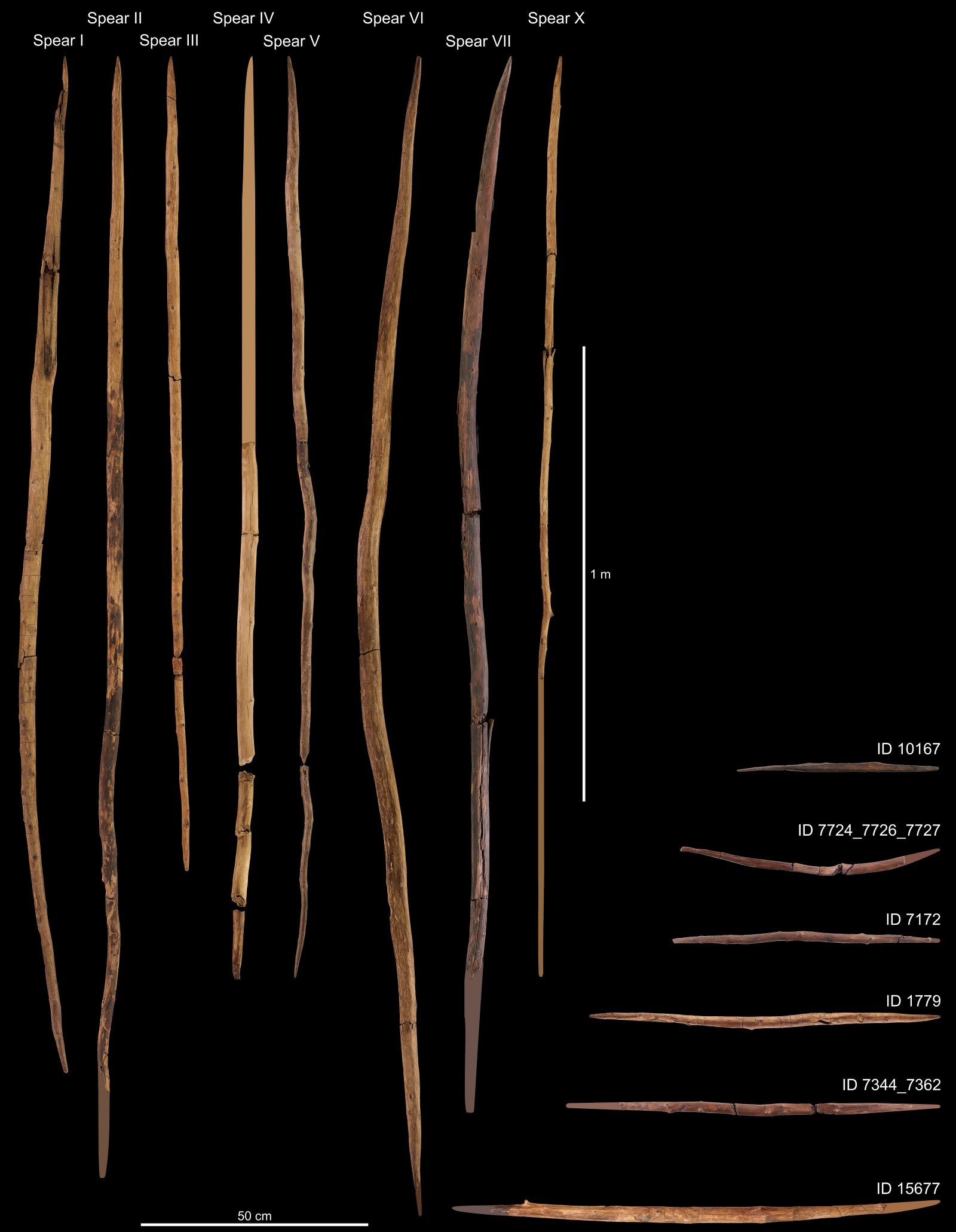

A recently-published study of around 300,000-400,000 year old wooden artefacts excavated from a coal mine in Schöningen, Germany between 1994 and 2008, indicated that these were not simply “sharpened sticks” but “technologically advanced tools” which required skill, precision, and time to build.

“In total, 187 wooden artifacts could be identified… demonstrating a broad spectrum of wood-working techniques” including “splitting, scraping or abrasion”, the research paper, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in April, said.

Periodising human prehistory

In technical terms, human ‘history’ began with the advent of writing. Everything before that is ‘prehistory’, studied primarily using archaeological evidence (physical remains of the past), although ethnographic research (study of human cultures, communities) can also provide important insights.

In the 19th century, Danish archaeologist Christian Jürgensen Thomsen came up with the first scientifically rigorous periodisation of human prehistory into Stone Age, then Bronze Age, and finally, Iron Age. Jürgensen’s basic chronology, based on our species’ technological advancement, has since risen to the status of dogma, although there have been significant refinements made to reflect diverse experiences across cultures.

The Stone Age began when hominids first picked up stone tools, some 3.4 million years ago (mya), in modern-day Ethiopia. This period, which went on till about 6,000-4,000 BP (Before Present), comprises 99% of human history. It is further divided into three periods — Palaeolithic (‘Old Stone Age’), Mesolithic (‘Middle Stone Age’, ), and Neolithic (New Stone Age).

The Palaeolithic period, which went on till about 11,650 BP in some places, is characterised by the use of rudimentary stone tools, and a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The Mesolithc period is a transitional phase. The Neolithic period, which first began roughly 12,000 BP in West Asia, is characterised by the development of settled agriculture, and the domestication of animals.

Preservation bias

Archaeological evidence forms the basis of the Stone Age classification — excavated sites from this period have unearthed stone tools, of different degrees of sophistication, which provide an insight into the lives and capabilities of its users.

As Charles Darwin wrote in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871): “To chip a flint into the rudest tool…demands the use of a perfect hand”. Even the most rudimentary stone tools required humans and human-anscestors to exhibit a degree of mental sophistication and physical dexterity that is rarely seen, if at all, in any other creature.

These capabilities, however, were not just limited to stone. Stone Age sites across the world also show evidence of a number of other materials being used, from bones and antlers, to clay, and some (very limited) metalworking. Evidence of woodworking, however, has been far more limited even though wood would have been an abundant resource.

Of the thousands of archaeological sites that can be traced to the Lower Palaeolithic (up to around 200,000 BP), wood has been recovered from less than 10, according to a report by The NYT. The earliest evidence of the use of wood, seen in the form of wooden dwellings, has been dated to only 700,000 BP — over two and a half million years after the earliest evidence of stone tools.

Archaeologists Aimé Bocquet and Michel Noël wrote in their highly influential paper, ‘The Neolithic or Wood Age’ (1985), “The absence of wooden remains from the Palaeolithic period… is certainly no indication that wood was not used”.

This sentiment is echoed by Thomas Teberger, leader of the team which carried out the recently published study. “We can probably assume that wooden tools have been around just as long as stone ones… But since wood deteriorates and rarely survives, preservation bias distorts our view of antiquity,” he told The NYT.

What Schöningen reveals

This is why the finds in Schöningen are so important. Due to the damp and oxygen-less conditions of the site’s soil, wood and other organic matter could not decompose — leading to the most well-preserved assemblage of prehistoric wooden artefacts in the world.

“Schöningen stands out due to its number and variety of wooden tools,” the recently published study, co-authored by Dirk Leder, Jens Lehmann, Annemieke Milks, Tim Koddenberg, Michael Sietz, Matthias Vogel, Utz Böhner and Teberger, said. “A minimum of 20 hunting weapons is now recognised and two newly identified artifact types comprise 35 tools made on split woods, which were likely used in domestic activities,” it said.

The Schoningen spears (Wikimedia Commons)

The Schoningen spears (Wikimedia Commons)

In the mid-1990s, archaeologist Hartmut Thieme discovered three wooden spears, along with stone tools and the butchered remains of more than ten wild horses, dated to around 400,000 years ago. This discovery of the world’s oldest preserved hunting weapons catapulted Schöningen — and Thieme — to global fame by upending the prevailing consensus that humans lived as simple scavengers till as recently as 40,000 years ago.

“… [T]he spears strongly suggest that systematic hunting, involving foresight, planning and the use of appropriate technology, was part of the behavioural repertoire of pre-modern hominids… [this] may mean that many current theories on early human behaviour and culture must be revised,” Thieme wrote in his paper ‘Lower palaeolithic hunting spears from Germany’ (1997). “Not only did they [pre-Homo sapiens] communicate together to topple prey, but they were sophisticated enough to organise the butchering and roasting,” Terberger told The NYT.

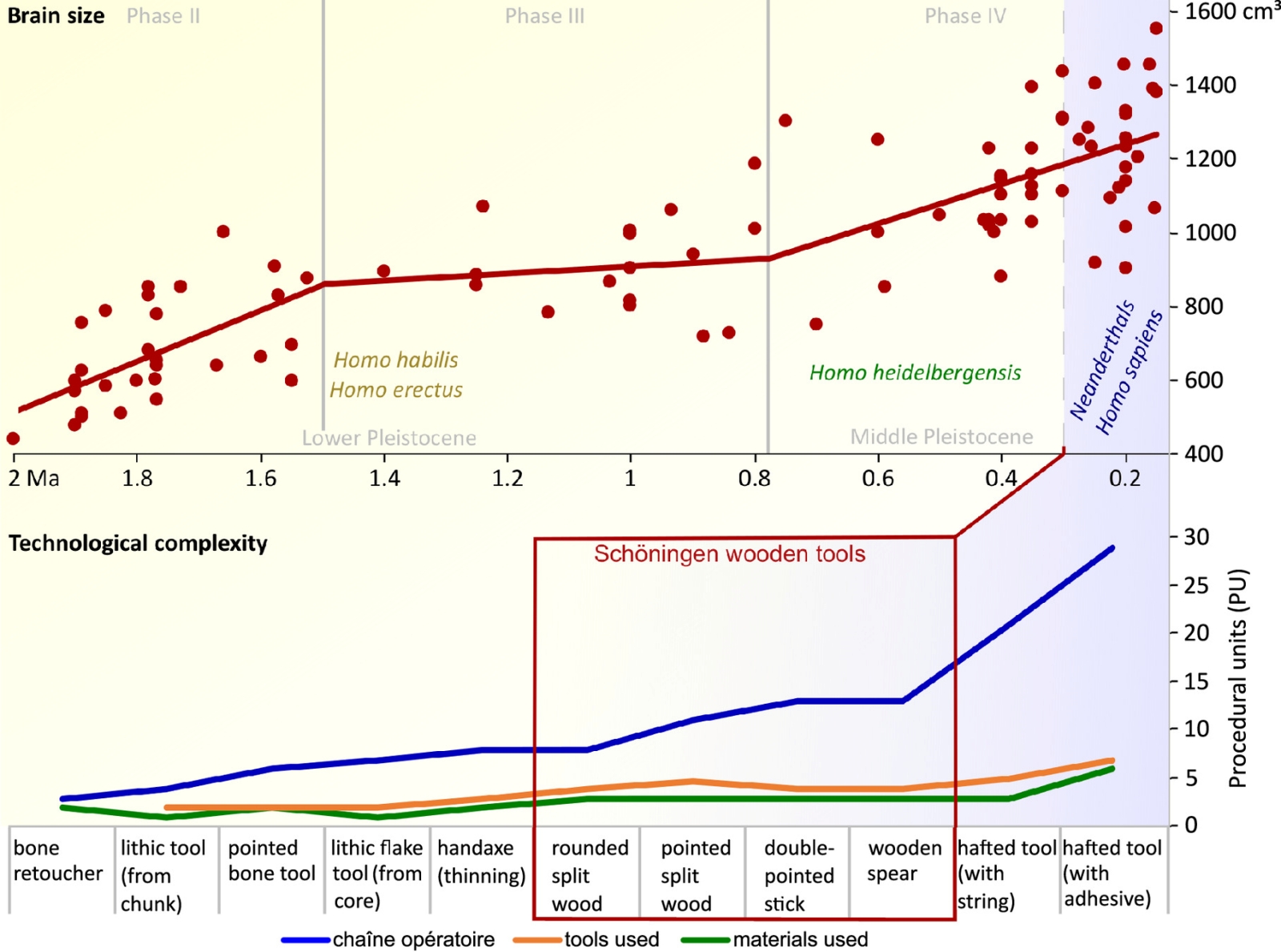

An illustration showing the correlation between brain size in hominids and complexity of tools used. (Derek Leder, Study)

An illustration showing the correlation between brain size in hominids and complexity of tools used. (Derek Leder, Study)

The new study shone further light on the technological complexity of Schöningen’s wooden artefacts. With the aid of 3-D microscopy (multiple sets of images are taken from a range of viewing angles, and collated and digitally constructed into a three-dimensional figure) and micro-CT scanners(CT scanners with micron — one millionth of a metre — resolution), researchers studied signs of wear or cut marks.

For instance, “until now, splitting wood was thought to have been only practiced by modern humans,” Dr Leder, the paper’s lead author, told The NYT. Moreover, some spears points also showed indications of being resharpened after breakage. “The wood that we identified as working debris suggested that tools were repaired and recycled into new tools for other tasks,” Dr Milks, also involved in the study, said.

In the face of paucity of evidence of prehistoric woodworking, the findings from Schöningen offer a more well-rounded glimpse into our past by showing the outstanding importance of wood as a raw material, as well as pre-modern humans’ sophisticated capabilities of working with it.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Jun 04: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05