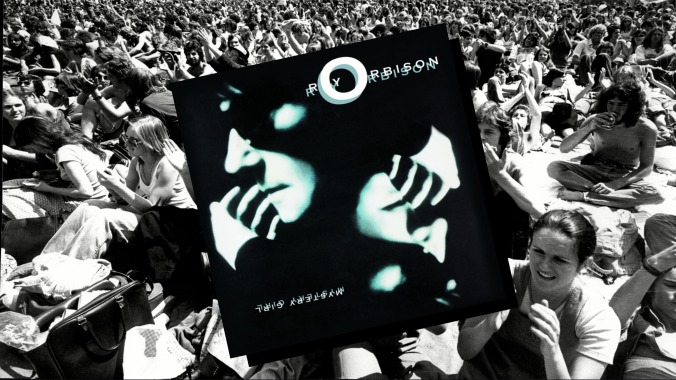

Time Capsule: Roy Orbison, Mystery Girl

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at Roy Orbison’s curtain call, a critical and commercial success that found the “Only the Lonely” singer surrounded by friends.

Music Reviews Roy Orbison

In 1987, Bruce Springsteen giddily inducted Roy Orbison into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. “Most of all, I wanted to sing like Roy Orbison,” Springsteen told the audience, recalling the recording sessions for Born to Run. “Now, everybody knows that nobody sings like Roy Orbison.” The Boss was certainly right that Orbison’s voice—three or four octaves in range and stretching from baritone to tenor—had been instantly recognizable since the singer’s chart-conquering string of hits back in the early ‘60s. However, it’s also true that Orbison—habitually clad in dark suits and tinted glasses with hair dyed jet black—had been largely relegated to the shadows by the same industry now honoring him. By the time Springsteen gave his induction speech, Orbison hadn’t released an album of new material in nearly a decade or notched a Top 40 single since the mid-‘60s. However, all of that was about to change in the months to come.

Shortly after Orbison got enshrined, the once-forgotten artist would see his star rise to heights only surpassed by his “Only the Lonely” and “Oh, Pretty Woman” heyday. That ascension would culminate in the release of 1989’s Mystery Girl, Orbison’s first studio album of all new material since 1979, and its globe-trotting hit single, “You Got It.” Suddenly, the singer once dubbed “The Big O” and “The Caruso of Rock”—known for his operatic voice and brooding ballads soaked in tears, loneliness and dreams—sat atop the music world alongside artists like Bon Jovi and Milli Vanilli. It’s a tale of triumph made all the more remarkable, and heartbreaking, because Orbison had already passed away from a heart attack in December of ‘88, a little less than two months before Mystery Girl would hit the shelves. In that light, the album acts as a final curtain call from Orbison, but it also closes the book on an unlikely, heartfelt comeback that saw the artists he had inspired nudge him back into the spotlight for one last encore.

Of course, nothing truly happens overnight. The revival leading to Mystery Girl had been slowly gaining momentum for over a decade, as the next generation of Orbison’s peers rekindled the public’s affection for his music. Everyone from Linda Ronstadt and Don McLean to Nazareth and Van Halen had scored hits with songs written or popularized by Orbison. Maybe the least likely boost came from filmmaker David Lynch’s bizarro use of Orbison’s “In Dreams” in his 1986 neo-noir thriller, Blue Velvet, where a lip-synched version serenades Dennis Hopper’s psychopathic gangster, Frank Booth, to the point of rage-filled tears. Orbison, a film buff in his own right, learned to appreciate the interpretation after originally having been horrified by the scene.

The Big O would jump on his own bandwagon as well, earning his first Grammy Award in 1981 for a duet with Emmylou Harris on “That Lovin’ You Feelin’ Again.” He would also re-record 19 of his greatest hits in 1987, after fearing that the original recordings might be destroyed due to legal issues facing former label Monument Records. Apart from the success of Mystery Girl, the zenith of Orbison’s revival might have been the now-iconic Cinemax special Roy Orbison and Friends: A Black and White Night. Springsteen played sideman to Orbison’s lead, and no less than Elvis Costello, Tom Waits, k.d. lang, Bonnie Raitt and Elvis Presley’s old backing band, among others, filled out the ranks for a night that showcased the singer’s body of work and undiminished power as a singer. lang recalls a grateful Orbison humbly thanking all involved and promising to return the kindness if possible.

Of all the friends Orbison made during the last couple years of his life, arguably none proved more impactful on his career and legacy than producer and Electric Light Orchestra frontman Jeff Lynne. Like Rick Rubin later did for Johnny Cash via the American Recordings series, Lynne would be the primary facilitator for what turned out to be Orbison’s final recordings. Running in Lynne’s crowd at the time found Orbison suddenly rubbing shoulders with fellow icons George Harrison, Tom Petty and Bob Dylan. The serendipitous overlap of Lynne’s production schedule would lead to Orbison hitching a ride with supergroup the Traveling Wilburys and those same bandmates becoming a critical part of his burgeoning Mystery Girl project.

The first thing that strikes the ear about Mystery Girl’s lead track and single, “You Got It,” is just how much it sounds like a Roy Orbison song. It’s instantly timeless and yet a throwback to simpler times. Like Orbison’s best songs, surprises wait at every turn, from the swelling strings lifting up his tag of “Baby…” on the choruses to the one-two of kettle drums and the subtle, shifting doo-wop vocals chiming in throughout the recording. Lynne, Orbison and Petty wrote the song in a single sitting together in Heartbreaker Mike Campbell’s garage, magically creating a tune that feels like it stepped right out of a ‘50s sock hop and yet sounds as fresh as ever when it pops on the radio today. And that’s perhaps the greatest credit to Lynne and all of Orbison’s collaborators on Mystery Girl. Never once does anyone ask Roy Orbison to do anything but be Roy Orbison. The global success of “You Got It” proved that Orbison, especially his voice, didn’t require an update. He simply needed a new stage to do what he had always done.

It’s that voice, of course—unparalleled in rock and roll history—that we lose ourselves in as listeners. The sheer catchiness of a pop classic like “You Got It” can sometimes distract us from just how dynamic Orbison’s voice can be across a single line or drawn breath, his vocal control unfathomable as he performs complicated acrobatics with the same offhand coolness of James Dean exhaling after a drag from a cigarette. And with Orbison, that vocal prowess never comes at the expense of emotion. On “California Blue,” he’s our everyman companion as we pine for a loved one separated by distance. He’s a tour guide through the head and the heart on “She’s a Mystery to Me.” We look up to hear Orbison floating above us on “A Love So Beautiful,” the heights his voice soars to symbolizing just how great a love this was that slipped away. Orbison’s second wife, Barbara, recalls eavesdropping alongside George Harrison as her husband nailed the performance in a single take. Lynne remembers that the song brought Orbison to tears the first time he heard the mix played back.

As a songwriter and recording artist, Orbison had never drifted too far away from the key themes that love always ends (often cruelly), only in our dreams do things work out and that we mark our time in this world mostly alone. Mystery Girl wears those same Orbison-tinted glasses across its compositions. “If only we could make of life what in dreams it seems,” he sings on the ethereal “In the Real World,” lamenting the inevitable pain and partings of life. Similarly, the rockabilly “(All I Can Do Is) Dream You” finds Orbison daydreaming about relighting an extinguished flame, curling his lip like Elvis on the titular chorus. On the beautiful closing track, “Careless Heart,” Orbison sings of the regret felt after having taken true love for granted. He concludes, “And I’m alone/ Alone with my lonely heart.” It’s hard to imagine anyone else singing a line like that and not coming across as mawkish. But Orbison had spent so many songs ensconced in loneliness over the decades that it never rings as anything but entirely sincere.

It’s sometimes difficult not to believe that some mysterious forces are at work. U2’s Bono tells the story of how he fell asleep to the soundtrack of Blue Velvet, which includes Orbison’s “In Dreams,” and woke up the following morning with the beginnings of “She’s a Mystery to Me” stuck in his head. That same evening, Orbison paid the band an impromptu visit following their concert at Wembley Arena, and Bono played him the song. It’s easy to see why the concept appealed to Orbison. While the phrasing feels at odds with most Orbison songs, the singer no doubt could relate to a story about a love that moves in such mysterious ways, oscillating between elation and torment. And while it still bears the DNA of a U2 song, Orbison elevates the drama of the bridges and choruses to places only his voice could take them. The song works so well that it makes sense the album’s title pulls from its lyrics.

Amid the star power of Beatles, Heartbreakers and Wilburys, it’s easy to overlook the other relationships that made Mystery Girl a very personal return for Orbison. “Windsurfer” saw him team up again with Bill Dees, his old songwriting partner from his MGM Records years. Inspired by their time together in California, the sand-covered tune tells the story, in true Orbison fashion, of an ill-fated surfer who only gets the girl of his dreams in his dreams. Orbison’s son Wesley penned the “The Only One,” a horn-accented rumination that perfectly captures the feeling of being the only one in the entire world tending to a broken heart. Barbara Orbison, who received a producer credit for “In the Real World,” sang backup vocals alongside her husband on the track. Roy Jr. also stepped up to the mic next to Dad when Tom Petty tapped out because nobody else in the room could hit certain notes unless they had the Orbison genes. To hear Barbara and the boys recall the sessions, it’s clear that Mystery Girl being a family affair meant the world to their beloved husband and father.

The final months of Roy Orbison’s life had left him with a bright musical future to look forward to. Sadly, a heart attack stole him away at 52 before he could finish his work and take that full victory lap. In April of ‘89, the charts showed that the departed singer had two Top 5 albums, Mystery Girl and the first Traveling Wilburys record. Orbison became the first deceased artist to achieve that distinction in the States since his friend Elvis Presley. And, in a poignant tribute, the Wilburys’ music video for “End of the Line” features a framed photo of Orbison during his verse and the rest of the band singing and strumming in a circle as their friend’s guitar sits in an empty rocking chair. Ironically, the artist who captivated us one last time with Mystery Girl after having built a career on singing about loneliness spent his final days surrounded by family and friends and once again adored by the music world. Only the lonely, indeed.