Rome's Vestal Virgins: protectors of the city's sacred flame

Chosen as young girls, the priestesses of Vesta, goddess of the hearth, swore a 30-year vow of chastity and in turn were granted rights, privileges, and power unavailable to other women in Rome.

Marcus Licinius Crassus was one of the richest and most powerful Roman citizens in the first century B.C. Yet he nearly lost it all, his life included, when he was accused of being too intimate with Licinia, a Vestal Virgin. He was brought to trial, where his true motives emerged. As the first-century historian Plutarch recounts, Licinia was the owner of “a pleasant villa in the suburbs which Crassus wished to get at a low price, and it was for this reason that he was forever hovering about the woman and paying his court to her.” When it became clear that Crassus’ wooing was motivated by avarice rather than lust, he was acquitted, saving both his and Licinia’s lives.

One of the most remarkable elements of this story is the fact that Licinia owned a villa in the first place. Unlike other women, Licinia could own property precisely because she was a Vestal Virgin. The story of her trial also reveals how that privilege came with a price: A Vestal Virgin had to abstain from sex, a sacred obligation to one of Rome’s most ancient customs that would continue until Christianity ended the cult in A.D. 394.

Vestal Veneration

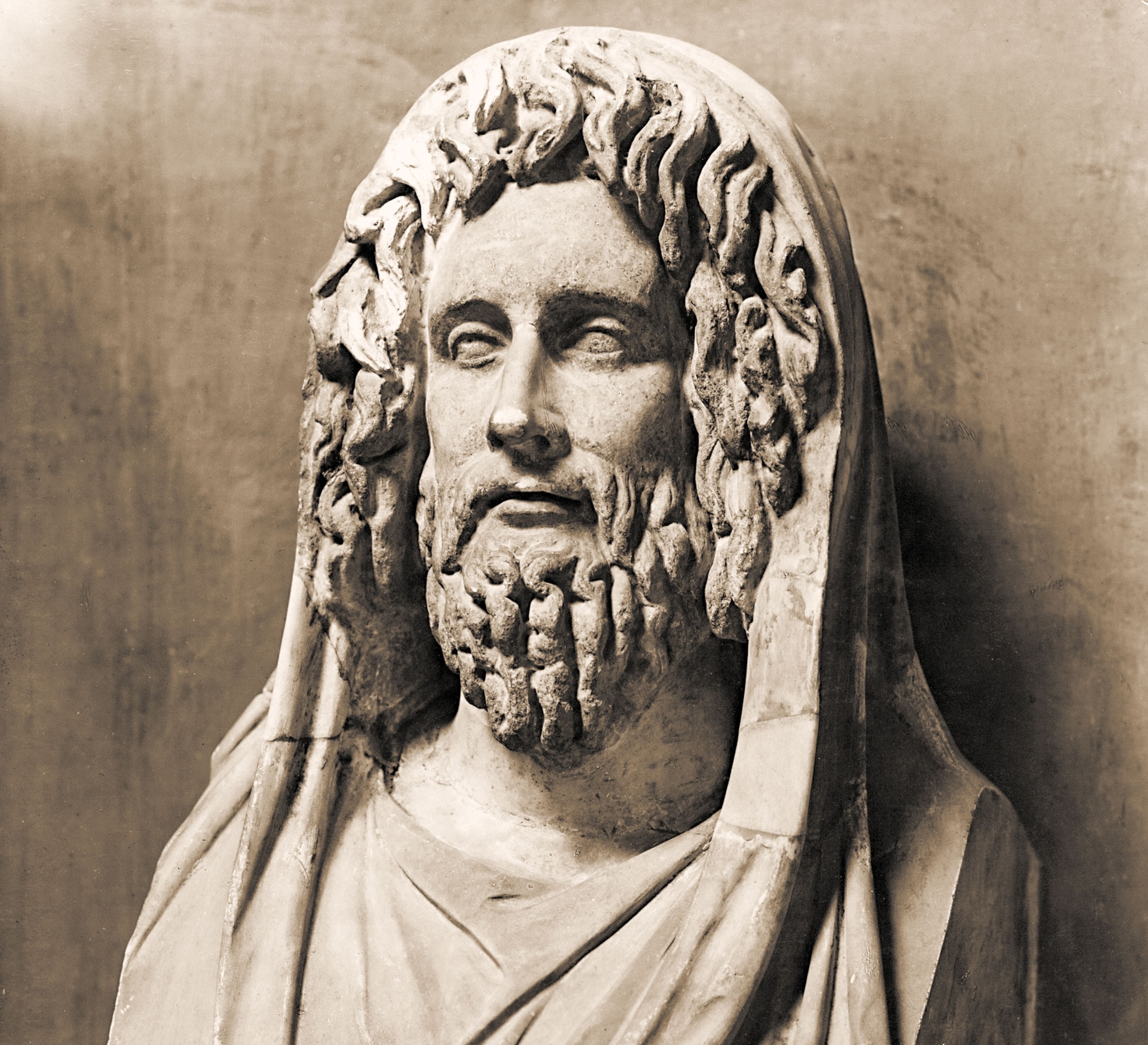

According to Roman authors, the cult was founded by Numa Pompilius, a semi-mythical Roman king who ruled around 715 to 673 B.C. Unlike most Roman religious cults, worship of Vesta was run by women. The hearth was sacred to this goddess, one of Rome’s three major virgin goddesses (the other two being Minerva and Diana). The rites surrounding the Vestals remained relatively fixed from the time of the Roman Republic through the fourth century A.D.

Six virgin priestesses were dedicated to Vesta as full-time officiates who lived in their own residence, the Atrium Vestae in the Roman Forum. The Vestals’ long tradition gave Romans a reassuring thread of continuity and may explain the Temple of Vesta’s traditional circular form, a style associated with rustic huts in the city’s deep past.

This place of worship, which lay alongside the Atrium, was where the priestesses tended the goddess’s sacred fire. Once a year, in March, they relit the fire and then ensured it remained burning for the next year. Their task was serious as the fire was tied to the fortunes of their city, and neglect would bring disaster to Rome.

To become a Vestal was the luck of the draw. Captio, the process whereby the girls were selected to leave their families and become priestesses, is also the Latin word for “capture”—a telling turn of phrase that evokes the kidnapping of women for brides that took place in archaic Rome. Records from 65 B.C. show that a list of potential Vestals was drawn up by the Pontifex Maximus, Rome’s supreme religious authority. Candidates had to be girls between the ages of six and 10, born to patrician parents, and free from mental and physical defects. Final candidates were then publicly selected by lot. Once initiated, they were sworn to Vesta’s service for 30 years.

On being selected, their life was spent at the Atrium Vestae in a surrogate family, presided over by older Vestals. In addition to room and board, they were entitled to their own bodyguard of lictors. For the first 10 years they were initiates, taught by the older priestesses. Then they became priestesses for a decade before taking on the mentoring duties of the initiates for the last 10 years of their service.

Training the Novices

After lots were drawn from the list of young girls who could serve Vesta, initiates were brought to the Atrium Vestae, where their training would begin. The training was overseen by the chief priestess, the Vestalis Maxima, who came under the authority of the Pontifex Maximus. The first 10 years were spent training for their duties. They would spend the second decade actively administering rites, and the final 10 were spent training novices. The chastity of the priestesses was a reflection of the health of Rome itself. Although spilling a virgin’s blood to kill her was a sin, this did not preclude the infliction of harsh corporal punishment. First-century historian Plutarch writes: “If these Vestals commit any minor fault, they are punishable by the high-priest only, who scourges the offender.”

Public monies and donations to the order funded the cult and the priestesses. In Rome religion and government were tightly intertwined. The organization of the state closely mirrored that of the basic Roman institution: the family. The center of life of the Roman home, or domus, was the hearth, tended by the matriarch for the good of her family and husband. In the same way, the Vestals tended Vesta’s flame for the good of the state.

Unlike other Roman women, Vestals enjoyed certain privileges: In addition to being able to own property and enjoying certain tax exemptions, Vestals were emancipated from their family’s patria potestas, patriarchal power. They could make their own wills and give evidence in a court of law without being obliged to swear an oath.

Thirty Years of Chastity

These rights came at a high price: 30 years of enforced chastity. Many historians believe that the health of the state was tied to the virtue of its women; because the Vestals’ purity was both highly visible and holy, penalties for a Vestal breaking her vow of chastity were draconian. As it was forbidden to shed a Vestal Virgin’s blood, the method of execution was immuration: being bricked up in a chamber and left to starve to death. Punishment for her sexual partner was just as brutal: death by whipping. Throughout Roman history, instances are cited of these grim sentences being passed. (See also: Legendary saints were real, buried alive, study hints.)

Jealousy or malice made the women vulnerable to false accusations. One story, celebrated by several Roman writers, concerns the miracle of the Vestal Virgin Tuccia, who was falsely accused of being unchaste. According to tradition, Tuccia beseeched Vesta for help and miraculously proved her innocence by carrying a sieve full of water from the Tiber.

Allegations of crimes against the Vestals’ chastity sometimes went to the top of the social order. The flamboyantly eccentric, third-century emperor Elagabalus actually married a serving Vestal Virgin. It is a sign of the enduring symbolic importance of the cult that this heresy was one major factor that led to his deposal and murder.

Vestal Vestments

The ceremonial dress of Vestals highlights their dual, and somewhat contradictory, embodiment of both the maternal and the chaste. Physical appearance was an integral part of their role, making them stand out as different from other women, but also echoing physical traits of conventional women.

Dressed in white, the color of purity, the Vestal Virgins wore stola, long gowns worn by Roman matrons. Hair and headdresses played an important symbolic function. The Vestal hairstyle is described in Roman sources using an ancient Latin phrase, the seni crines. Historians cautiously agree it means “sixbraids,” and is mentioned as the coiffure of both Vestal Virgins and brides. A Vestal wore the suffibulum, a short, white cloth similar to a bride’s veil, kept in place with a brooch, the fibula. Around their heads they wore a headband, the infula, which was associated with Roman matrons.

Daily rites for Vestals were often centered around the temple. Most important was maintaining the holy fire. If the fire went out, the attending Vestals would be suspected not only of neglect but also of licentiousness, since it was believed impurity in a Vestal’s relations would cause a fire to go out. Other typical duties included the purification of the temple with water, which had to be drawn from a running stream. In readiness for the numerous festivals that required their attendance, the priestesses were required to bake salsa mola, a cake of meal and salt that was sprinkled on the horns of sacrificed animals. Important religious festivals included the Vestalia, dedicated to their goddess, Vesta, and the Lupercalia, which highlights the contradictory role of the Vestal Virgins, as it was closely associated with fertility.

A Roman Tradition

Romans believed the cult of the Vestal Virgins was instituted under the eighth-century B.C. king Numa Pompilius, the successor of Rome’s founder, Romulus. First-century A.D. historian Plutarch wrote that Numa may have “considered the nature of fire to be pure and uncorrupted and so entrusted it to uncontaminated and undefiled bodies.“ Numa is credited by Livy, in his History of Rome, with formalizing other key Roman cults, including those of Jupiter and Mars. Many historians believe Numa was legendary, and that the worship of Vesta and other cults developed slowly out of pre-Roman customs, perhaps dating back to the older Etruscan culture that dominated Italy before the rise of Rome.

In the innermost part of their temple, the priestesses looked after their secret talismans. Among these objects was the sacred phallus, the fascinus, the representation of a minor god of the same name. The fascinus (the root of the word “fascinate”) is closely bound with magic and fertility. It was also in this part of the temple that they probably kept the palladium, the statue of Pallas Athena that the legendary founder of Rome, Aeneas, brought to Italy after the destruction of Troy, his home city—another aspect of the Vestal cult that tied Rome’s origins into an ennobling and ancient tradition.

Romans regarded these priestesses with a sense of awe. Plutarch points out “they were also keepers of other divine secrets, concealed from all but themselves.” It was believed they possessed magical powers: If anybody condemned to death saw a Vestal on his way to being executed, he was to be freed, so long as it could be proven the meeting was not by design. Vestals, it was said, could stop a runaway slave in his tracks.

The privileged position of the Vestal Virgins in Roman society survived for more than a thousand years, passing through Rome’s changing systems of monarchy, republic, and empire. The cult would not, however, survive Christianity. In A.D. 394 Theodosius closed the House of the Vestals forever, freeing the virgins from their obligations, but also removing their privileges.

Even as their flame was extinguished, aspects of the cult may have passed into the new faith as it swept through the Mediterranean. Just as the position of the Pontifex Maximus lived on in the papal title “pontiff,” young women in the early years of Roman Christianity embraced virginity and celibacy in their desire to be “eunuchs for the love of heaven.” Scholars believe the role of the Christian nun was inspired, in part, by the chaste figures who dutifully tended the holy flame of Vesta.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- These pelicans are starving to death—despite plenty to eatThese pelicans are starving to death—despite plenty to eat

- The world's largest fish are vanishing without a traceThe world's largest fish are vanishing without a trace

- We finally know how cockroaches conquered the worldWe finally know how cockroaches conquered the world

- Why America's 4,000 native bees need their day in the sunWhy America's 4,000 native bees need their day in the sun

- Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa

- Paid Content

Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa

Environment

- 2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year

- Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species

- Paid Content

Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species - These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new wayThese images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way

- What rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

History & Culture

- When a people's stories are at risk, who steps in to save them?When a people's stories are at risk, who steps in to save them?

- I wrote this article with a 18th century quill. I recommend it.I wrote this article with a 18th century quill. I recommend it.

- Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’

- These modern soldiers put Bronze Age armor to the testThese modern soldiers put Bronze Age armor to the test

- Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?

- They were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendaryThey were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendary

Science

- How being the oldest or youngest sibling shapes your personalityHow being the oldest or youngest sibling shapes your personality

- Tuberculosis is rising in the U.S. again. How did we get here?Tuberculosis is rising in the U.S. again. How did we get here?

- Are ultra-processed foods as addictive as cigarettes?Are ultra-processed foods as addictive as cigarettes?

- Epidurals may do more than relieve pain—they could save livesEpidurals may do more than relieve pain—they could save lives

- Why the world's oldest sport is still one of the best exercisesWhy the world's oldest sport is still one of the best exercises

Travel

- How to plan the ultimate island-hopping adventure in ScotlandHow to plan the ultimate island-hopping adventure in Scotland

- Why this Scottish island is best explored by waterWhy this Scottish island is best explored by water

- Return to the wild: Connecting with Canada's heritage

- Paid Content

Return to the wild: Connecting with Canada's heritage - A practical guide to cycling Slovenia Green RoutesA practical guide to cycling Slovenia Green Routes

- This road trip journeys through Albania's wild, blue heartThis road trip journeys through Albania's wild, blue heart