He was the last king of America. Here’s how he lost the colonies.

The British monarch is often depicted as the chief villain in America’s origin story—but what role did he really play in sparking the revolution?

On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence. The document not only proclaimed the sovereignty of the United States, but it also cast King George III of Great Britain as the chief villain in America’s origin story.

As a constitutional monarch, George had not created the policies that sparked conflict in the colonies—that was Parliament’s job. So, why did the Declaration vilify the king, and what role did he play in the American Revolution?

Though the king did not personally trigger the shot heard round the world, he nonetheless helped pave the path toward war. Here’s how he became the last king of America.

Father of the empire

When 22-year-old King George III inherited his grandfather’s throne in 1760, he also inherited an empire that extended from North America to Asia. George did not see himself strictly as a head of state. Instead, his subjects—whether in York or New York—were his children, he believed, bound to him by obedience and affection.

Even though George did not have much legislative power as a constitutional monarch, he remained engaged with politics and understood that it was his duty to give the royal assent to Parliament’s bills.

(George III was married to Queen Charlotte—was she Britain's first Black queen?)

George also leaned into his role as Britain’s paterfamilias. He emphasized order, duty, and integrity in both family and national life. In George’s world, a king had a duty to model virtue for his subjects—and they had a duty to obey.

What did George’s subjects think of him? Throughout the 1760s, North American colonists embraced him. Even future Founding Father Benjamin Franklin swelled with monarchical pride when he attended George’s coronation in 1761. Two years later, Franklin praised the young king’s “virtue and the consciousness of his sincere intentions to make his people happy.”

Rising tensions

Even as George idealized the stability of a well-ordered imperial family, Britain’s political landscape tremored, widening the gulf between North American colonists and members of Parliament in London.

George’s reign had begun while Britain was knee-deep in the Seven Years’ War against France and its allies. When the war ended in 1763, Britain gained a newly enlarged empire with land in North America that stretched all the way to the Mississippi River.

It came at a cost. Britain had amassed significant war debt. To offset the debt, Parliament introduced a succession of taxes in the American colonies. Since British troops needed to be stationed on American soil, they reasoned, the colonists should foot the bill.

(How the Declaration of Independence wooed Americans away from Britain.)

The taxes outraged colonists, who initially directed their ire at the politicians who governed them, not the king who ruled them. How could members of Parliament, men an ocean away, impose taxes without their consent?

Parliament made matters worse by passing the Tea Act in May 1773, which colonists complained gave the British East India Company a significant competitive edge in the tea market. Taking matters into their own hands in December that year, revolutionaries in Boston stormed the city’s harbor, boarded British merchant ships, and hurled tea into the sea.

A firm hand

News of the Boston Tea Party, an act of disorder and disobedience, shocked George. Holding to his belief in the authority of Parliament and his role as imperial father, George supported a firm hand against the colonists. When Parliament passed four acts in early 1774 that undercut Massachusetts’ ability to govern itself, he approved.

Colonists had a nickname for these new laws: the Intolerable Acts. And though they had targeted Massachusetts, scene of the Boston Tea Party, colonists throughout North America united in their indignation. What rights would Parliament take away next?

(America declared independence on July 2—so why is the 4th a holiday?)

As tensions rose, most of the American colonies sent delegates to the Continental Congress in September 1774 to respond to what they called Parliament’s “oppressive restrictions.” It was, delegates argued in their October petition to the king, an affront on English liberty, their birthright as crown subjects.

In the petition, delegates appealed to George for assistance. “We your majesty’s faithful subjects,” it began, “[beg] to lay our grievances before the throne.” Delegates likened the Intolerable Acts to “being degraded into a state of servitude” and expressed their grievances because “silence would be disloyalty.”

George stood with Parliament.

The spark of war

On a chilly, soggy April morning in 1775, tensions between subjects and sovereign boiled over when colonial militiamen and British troops clashed in Lexington and Concord, villages near Boston. The Revolutionary War had begun.

(What was the "shot heard round the world"?)

George saw the conflict as an opportunity. “I cannot help being of [the] opinion that with firmness and perseverance, America will be brought to submission,” he assured the Secretary of State for the Colonies Lord Dartmouth. George added, “England […] will be able to make her rebellious children rue the hour they cast off obedience.”

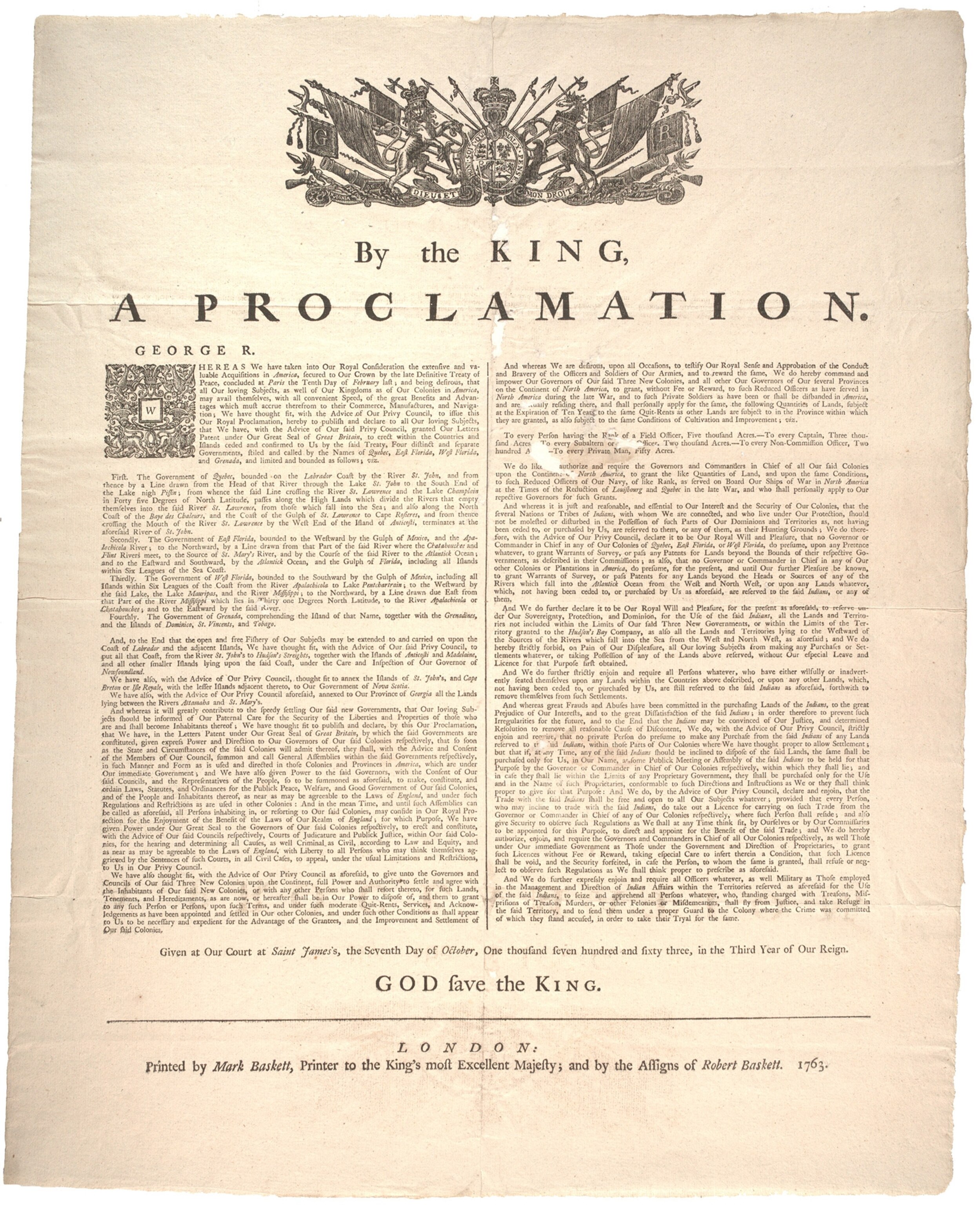

The Continental Congress made one final petition to George in July 1775. Refusing to receive it, he instead issued a royal proclamation that labeled the war a “rebellion” and denounced the revolutionaries for “traitorously preparing, ordering, and levying War against Us.”

Whatever last shred of loyalty colonists felt to George vanished. His uncompromising hostility toward revolutionaries inspired Thomas Paine to remark in 1776, “Even brutes do not devour their young, nor savages make war upon their families.”

George’s imperial family was broken; it suffered a violent, irreversible estrangement.

The last king of America

As far as the Continental Congress was concerned, George was no longer its king. Instead, the Declaration of Independence outlined 27 grievances against George and labeled him “a Tyrant […] unfit to be the ruler of a free people.”

George never regained his grasp on the American colonies. Instead, his former subjects burned his effigy and toppled a statue of the king in New York.

(That toppled statue was just the beginning—here's how the colonists rebelled against the king.)

In 1785, two years after the smoke of the Revolutionary War had cleared, George received the new ambassador from the United States of America: John Adams, one of his former subjects. Adams later claimed George told him the reasoning behind his actions in the years leading up to the war: “I have done nothing in the late Contest, but what I thought my Self indispensably bound to do by the Duty which I owed to my People.”

George’s duty to preserve the empire, stand with Parliament, and restore order within the imperial family ultimately led to its rupture, making him the last king of America.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- The world's largest fish are vanishing without a traceThe world's largest fish are vanishing without a trace

- We finally know how cockroaches conquered the worldWe finally know how cockroaches conquered the world

- Why America's 4,000 native bees need their day in the sunWhy America's 4,000 native bees need their day in the sun

- Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa

- Paid Content

Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa - Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

Environment

- 2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year

- Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species

- Paid Content

Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species - These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new wayThese images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way

- What rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

History & Culture

- Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’

- These modern soldiers put Bronze Age armor to the testThese modern soldiers put Bronze Age armor to the test

- Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?

- They were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendaryThey were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendary

Science

- Why the world's oldest sport is still one of the best exercisesWhy the world's oldest sport is still one of the best exercises

- What if aliens exist—but they're just hiding from us?What if aliens exist—but they're just hiding from us?

- Can a spoonful of honey keep seasonal allergies at bay?Can a spoonful of honey keep seasonal allergies at bay?

- Scientists just dug up a new dinosaur—with tinier arms than a T.RexScientists just dug up a new dinosaur—with tinier arms than a T.Rex

Travel

- Visit Rotterdam as it transforms itself into a floating cityVisit Rotterdam as it transforms itself into a floating city

- How to get off the beaten track in Northern LanzaroteHow to get off the beaten track in Northern Lanzarote