- India

- International

Keeping the flame alive: What made Deepa Mehta’s Fire such a pathbreaking film

Twenty years later, looking back at what made Deepa Mehta’s Fire such a pathbreaking film and examining its relevance today.

In 1996, a film exploring homosexual love was released without a single cut and garnered criticism and praise in equal measure.

In 1996, a film exploring homosexual love was released without a single cut and garnered criticism and praise in equal measure.

Nearly 20 years ago, unaided by Twitter and Facebook, a film went viral in India. Fire was the first in mainstream Indian cinema to explore homosexual love. It introduced a taboo subject to the audience of the world’s largest film-producing and film-viewing nation. Off screen, it was the target of vandals, spawned a civil society movement, led to adjournments in Parliament and exposed men’s underwear as agitprop. In the year of its 20th anniversary, Fire retains its position as a relevant reference for films on gender relationships in India. Last year, the British Film Institute selected Fire as one of its top 10 feminist films.

In 1996, the noise was still in the future. The film, in which two sisters-in-law from a traditional household fall in love with each other, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September. “People hadn’t seen such a film — sadly, in these 20 years, hardly any films have been made on same-sex relationships. For India, it is definitely a landmark film,” says Nandita Das, who played the younger woman, Sita. Fire became the darling of the festival circuit, picking up 14 awards in France, Spain, the UK, the US and Germany, among others.

The family drama is the study of a conservative society — represented by its microcosm, the home — in which someone challenges the rules. A middling businessman, Ashok (Kulbhushan Kharbanda), lives with his wife Radha (Shabana Azmi), his brother Jatin (Javed Jaffrey), mother Biji (Kushal Rani) and the man-servant Mundu (Ranjit Chowdhry) in a clustered Delhi neighbourhood. Men and women have clear gender-defined roles that neither challenges until the younger brother’s bride arrives. “Isn’t it amazing we’re so marked by customs and rituals? Somebody just has to press my button, this button marked tradition and I start responding like a trained monkey. Do I shock you?” she tells Radha during Karva Chauth. “Yes,” replies Radha, fondly. “You’re lovely,” says Sita, giving her sister-in-law a hug.

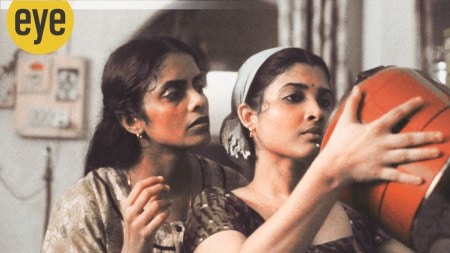

A scene from the film featuring Shabana Azmi and Nandita Das

A scene from the film featuring Shabana Azmi and Nandita Das

“I wanted to make a film about a middle-class household where two female protagonists fall in love and to examine the outcome of the choices they make, specifically its impact on the family, society and themselves. The lesbian angle is not incidental, but I had no clue the film would be so controversial,” says Indo-Canadian filmmaker Deepa Mehta.

In her book, Fire: A Queer Classic, scholar and author Shohini Ghosh writes, “Riyad Wadia’s independent, experimental film BomGay (1996) inaugurated queer films in India…Wadia’s next film A Mermaid Called Aida (1996) is a feature-length documentary on well-known transsexual Aida Banaji. Like most documentaries, both films circulated through an expansive network of non-commercial screenings…The films of Prathibha Parmar, a UK-based director of Indian origin, also exerted considerable influence among the emergent gay and lesbian movement in India.” Amol Palekar’s Daayra (1996) and Kalpana Lajmi’s Darmiyaan (1997) and Tamanna (1997) had queer central protagonists. Fire released in English and Hindi like any other mainstream film and claimed public space for an alternative identity.

It was on a snowy day in Ontario, Canada, that Mehta had looked out of her cottage and seen a blanketed landscape. Looking at it, she had imagined a scene — of a young couple on a visit to the Taj Mahal. He smokes against a red sandstone wall, she wanders alone. “Don’t you like me?” asks Sita. Jatin grunts, “Look, we’ve only been married for three days.” In the cracks of a nascent heterosexual relationship, Mehta had one of her earliest scenes for Fire.

Mehta’s childhood had been spent in a home in Amritsar bustling with aunts and uncles. She moved to Canada, where she still lives, in 1973 with her then husband Paul Saltzman, a filmmaker and producer. Fire drew Mehta back to her family home. Her mother and aunts had had arranged marriages with men they did not know. “I started thinking of a house in Delhi and its inhabitants. A woman comes into an arranged marriage and I thought of a sister-in-law because there are lots of them around,” she says.

The dutiful wife in the film is named after Krishna’s playful paramour while the questioning daughter-in-law is a namesake of Ramayana’s submissive heroine. When Radha cannot have children, Ashok does not turn her out or take on another woman “because he is a saint”. Instead, he practises self-control by sleeping next to her without touching her. After he is satisfied with his willpower, Radha is sent away to her separate bed. “You start by keeping all objects of temptations around you and testing yourself against them until all desires leave your mind and body. Desire is the root of all evil,” he says. “How does it help me?” Radha asks, gently. “By helping me, you are doing your duty as a wife,” he answers.

The attack at Delhi’s Regal cinema during a screening of Deepa Mehta’s Fire in December 1998

The attack at Delhi’s Regal cinema during a screening of Deepa Mehta’s Fire in December 1998

Within the walls of the house — the first zone of conflict for many queer people — heterosexuality is a norm, for it takes patriarchy into the future by propagating sons. “What you have done is a sin in the eyes of god and man,” shouts Ashok when he finds out about Radha’s relationship with Sita. “What can be more challenging to patriarchy than women saying they don’t need men?” says Anjali Gopalan, founder of the rights group Naz Foundation and a petitioner against Article 377 that criminalises homosexuality in India. “The issue of lesbianism hasn’t been accepted like male homosexuality. Unlike men who are gay, women who see themselves as lesbians… are still at the bottom of the totem pole. The film helped because a lot of people who were thinking of rights got together to… talk about inclusiveness,” she adds.

Mehta says the two women would have fallen in love despite their husbands. “You can be unaware of having a particular gender preference until you confront it — see the film Carol. Two women, one married, one not, fall in love. That’s what happened to Radha and Sita,” she says.

Azmi plays Radha with quiet luminosity. The actor had won multiple National Film Awards for films such as Ankur (1974), Arth (1982) and Paar (1984) by the time she took on Fire. Thoughtful, politically astute and conscious of the world outside Bollywood, Azmi says Fire was not an easy choice.

Shabana Azmi, Nandita Das and director Deepa Mehta in conversation with writer William Dalrymple at the Women in the World conference last year

Shabana Azmi, Nandita Das and director Deepa Mehta in conversation with writer William Dalrymple at the Women in the World conference last year

When ‘Women in the World’, a summit on the position of the female in the changing global scenario, was held in India last year, Fire was one of the topics. Speaking on it, Azmi said, “I was working with women in the slums at that time and was aware that this film would be used against me because the things we were doing were, in any case, not run of the mill…” Her husband, filmmaker-poet Javed Akhtar lent his support ,but it was his daughter Zoya, now an award-winning filmmaker, who swung her decision. “I said, ‘It’s got a lesbian angle’ and Zoya said, ‘So?’ Here was a 20-year-old for whom the lesbian angle was not even a consideration. That’s what led me to think that different people would think differently,” she said.

Fire opened in the country at the International Film Festival of Kerala 1997, and reports say that delegates gatecrashed the Kairali theatre to watch it. “I was so glad that the first public screening in India was to be in Kerala. I thought people there were exposed to good cinema, it has a rich history of art, culture and literature and it is a matrilineal society with the highest literacy rate in the country. But when the screening began, I was shocked by the response,” says Das. The mostly male audience was “laughing and clapping at all the wrong places”. The denouement in Fire comes when the affair has been exposed. Seeking support and understanding, Radha goes to her mother-in-law, whom she has nurtured throughout the film. Holding her arms, the frail Biji rises from the bed and, as their faces come close, spits into Radha’s eye. “In the screening in Thiruvananthapuram, they were cheering. It was the most disappointing reaction anywhere in the world,” says Das.

Das had completed her post-graduation in social work from Delhi University, acted with Safdar Hashmi’s street theatre group and was a part of an NGO on women’s rights when she was introduced to Mehta on a visit to Pandit Jasraj’s family in Mumbai. The daughter of artist Jatin Das and writer Varsha, former director of the National Book Trust, she had grown up in a liberal home where they discussed everything. “Somehow, we had never talked about homosexuality,” she says. The script spoke loudly to her. “The film was about the lack of choices that women have…It was about caring, compassion, filling of voids that women have in meaningless marriages,” Das says.

The relationship between Radha and Sita turns sexual after Radha discovers Sita crying in her room, while her husband is away with his girlfriend Julie. The women embrace and Sita spontaneously kisses Radha on the mouth. They grow closer every day. The camera moves intimately during the lovemaking scenes, treating it in warm interplays of shadow and colour. Das recalls those moments of shooting — “I was asked to caress Shabana’s face lovingly and I didn’t do it properly. Here we were, three heterosexual women, making a film on homosexual love,” she says. “Think of a man you are really attracted to,” Mehta told her. Das said, “But she’s not a man!”

Fire opened across India in mainstream cinemas in the winter of 1998. The film recorded 80 per cent collections in three weeks until trouble visited it on November 25. Two dozen men of the Jain Samata Vahini of Mumbai wanted Maharashtra’s minister of state for cultural affairs, Anil Deshmukh, to ban the film but failed. On December 1, Shiv Sainiks ransacked Cinemax theatre in Goregaon, Mumbai, and forced the manager to call off all other shows. A second hall, New Empire, cancelled screenings. “There are two scenes showing sexual acts between two women. Is it fair to show such things which are not a part of Indian culture? Masturbation is a common practice but can you do it openly?” asked Sena chief Bal Thackeray. After Mumbai, it was the turn of Regal cinema in Delhi. Ten minutes into the screening, Sainiks, led by Jai Bhagwan Goyal, drove out the audience, vandalised the theatre and raised slogans threatening anybody who attacked Bhartiya sanskriti.

Goyal, the then Delhi chief of the Shiv Sena hasn’t changed his mind about the film in 20 years. “The film insulted Radhaji and Sitaji. It insulted the Ramayana. We asked them not to show the film as it would hurt sentiments of the Hindus, but did they listen? Everybody knows what men and women do in their bedroom after marriage, but will we let them do it openly?” he says. Goyal split from Thackeray’s party in 2008 and is now national president of the Rashtrawadi Shiv Sena. After Sena’s attacks, Fire stopped screening in Delhi, Pune and Surat, among others.

With capitalism, art shares a fundamental trait. The consumer — also known as connoisseur — is king. The most-important verdict for Fire came from the audience. “That night after Fire was attacked, there was a vigil by candlelight at Regal. As far as the eye could see, there were women and men with placards that said, ‘We are Indians and we are lesbians’. I was like, ‘Holy shit, this is cool,’” says Mehta. When the right-wing Bengal Provincial Hindu Mahasabha arrived at Chaplin theatre in Kolkata, they were met by a wall of men and women who told them politely that the show would go on. A hall in Patna owned by Krishna Ballabh Prasad Narayan Singh aka Bauaji ran Fire to houseful crowds, undisturbed. “I have watched the film and not found it objectionable. Lesbianism may be a new subject in Hindi films but why should one protest about it?” he said. Singh was state chief of RSS in Bihar.

Actor Dilip Kumar, who had received the Nishan-e-Imtiaz from Pakistan, came out in support of Fire by filing a PIL with the Supreme Court. A group of Sainiks dressed in chaddis gathered outside the actor’s Pali Hill residence carrying placards saying, “Nangon ka neta Dilip Kumar”. Kumar was branded “Pakistani”. Civil society supporters of Fire took out a candlelight march in Delhi to the residence of then Home minister LK Advani and compelled him to intervene. In Rajya Sabha, where Azmi was a member, parties marched to the well and forced the Chair to adjourn the House twice.

Asha Parekh, chief of the Board of Film Certification at the time, was nicknamed Ms Scissorhands for her penchant to insert cuts. Fire, however, was released without a single snip. “Then, after it was pulled out of the theatres and re-referred to the Board, praise the Board, they re-released it without a single cut. That, I do not believe, can happen in today’s society,” said Azmi at Women in the World, a few days after James Bond’s kiss in Spectre had been censored to half its length.

Gopalan points out that, while the attacks were on lesbianism, the support was for freedom of expression. The candlelight activists were not protesting for a lesbian film — they were protesting for a film. Ghosh adds, “Fire was a watershed moment in the feminist debate on censorship. Till that time, a number of feminist groups had been demanding censorship in the name of obscenity and vulgarity. But the attack on Fire compelled them to re-think their positions. At the Regal protest, a lot of people joined in, whether they supported queer rights or not. They were there to support free speech.”

In the two decades since its release, each player involved in Fire has become assertive — from the zealots to civil society, from the Censor Board to the feminist community. “Fire was a turning point for me. Earlier, when I was asked if I was lesbian, I would quickly say, ‘No, no, you don’t have to be a lesbian to act as a lesbian’. Now I say, ‘Why is that question even relevant to the work I do?’ I have always seen my films as a means and not an end. My work on human rights issues and that in films started coming together, feeding on each other… Fire helped me understand more deeply what an insensitive and hypocritical society we live in,” says Das before asking, “Why hasn’t there been 20 more Fires?”.

However, even though progress has been slow, mainstream cinema hasn’t let go of the precedent set by Fire altogether. My Brother Nikhil (2005) and I Am (2010) by Onir have featured queer relationships, but it was Abhishek Chaubey’s Dedh Ishqiya — the story of two women finding love amid the paling splendours of a palace — that stopped heartbeats in 2014. It is a sign of how much India has changed that Chaubey was unafraid of a backlash and was proved right. “There are films about boy-girl relationships, this was girl-girl relationship. So what?” he says.

Click for more updates and latest Bollywood news along with Entertainment updates. Also get latest news and top headlines from India and around the world at The Indian Express.

May 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05