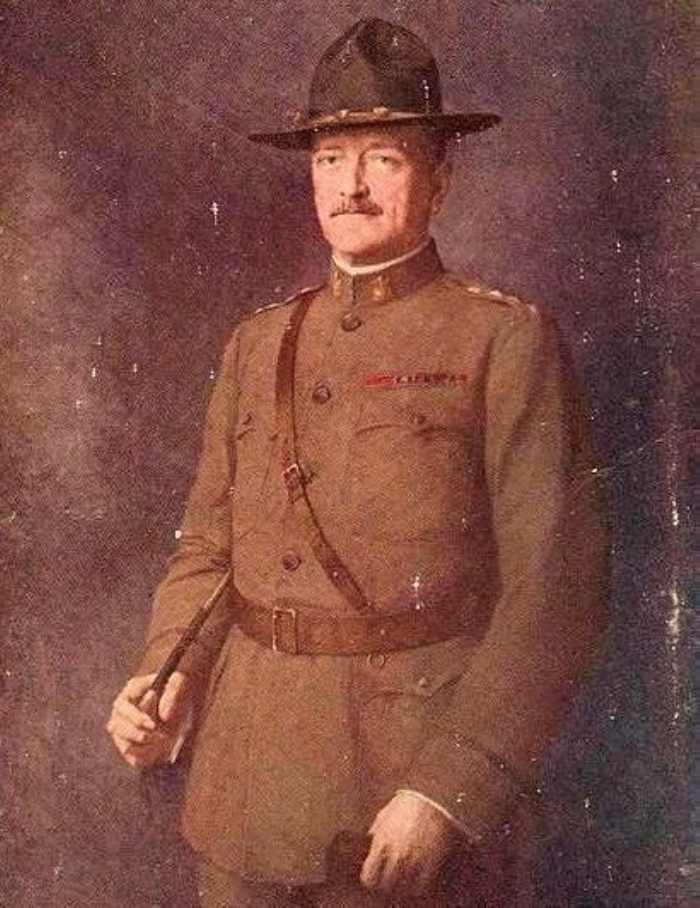

General John “Black Jack” Pershing: His Life and Accomplishments Before World War I

Early Years

John Pershing was no stranger to war. Born in Missouri at the brink of the Civil War, he witnessed the ugliness of an armed conflict as a young boy. When he was only three years old, a band of Confederate sympathizers raided Laclede, Missouri, harassing and threatening anyone supporting the Union, including John’s father, John Fletcher Pershing. The state of Missouri was divided during the Civil War, with Union allegiance in the northern part of the state and a Confederate stronghold to the south. In Missouri and the other border states, the war brought conflicts even to small communities, pitting one-time friends against each other. John Sr. and his wife, Ann, did what they could to shelter John and his other siblings from the war that ripped through the nation.

After the Civil War, much of the nation went into economic depression, forcing the once prosperous John Fletcher to lose his store and land in the depression of 1873. John Sr. became a traveling salesman to feed his family while his eldest sons, John and Jim, hired out to local farmers as laborers. The hard work and trials of his youth forged in John the spirit of an ardent and determined man. He had an interest in studying the law, but his family’s finances didn’t allow for advanced education. Instead, he took a job as a janitor and then as a teacher at a public school for African American children.

College

Pershing saved money on his $35 per month wage and by 1880 he was able to attend the nearby Kirksville Normal School where he studied a variety of subjects. After two years of study, his college days were cut short when a newspaper article alerted him to a competitive exam for entrance into the United States Military Academy at West Point, Maryland. The school was highly regarded, offered free tuition, and would expose him to an invaluable circle of friends. He studied hard for the entrance exam and beat out 18 other competitors for a coveted spot at West Point.

Beginning of Military Career

When he entered West Point, he did not intend to be a soldier; rather, he hoped it would be a steppingstone in his pursuit of the study of law. Once at “the Point,” his goal changed; the rigid life of a soldier suited him. His hard work and discipline paid off as he was the class president all four years. In June 1886 he graduated 30th in a class of 77. After graduation he joined the 6th Cavalry at Fort Bayard, New Mexico, to fulfill his mandatory service requirement.

The 6th Cavalry was part of General Nelson A. Mile’s campaign to suppress the uprising of the Lakota (Sioux) Indians. In December 1890, Pershing and the 6th Cavalry were hastily sent to Fort Mead, South Dakota, to prevent a feared Indian uprising. Although Pershing and his unit did not participate in the slaughter at Wounded Knee Creek, he arrived three days later to participate in minor skirmishes with the few remaining hostiles. Little did he realize that the events at Wounded Knee were the final chapter of the history of the Native Americans as a free people.

University of Nebraska

After a brief assignment at Fort Niobrara in Nebraska, Pershing was appointed professor of military science and tactics at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln. He had a connection with the university as two of his sisters had attended the school. In addition to teaching mathematics, he was the commandant of the university’s battalion. The chancellor of the university, James H. Canfield, liked the new military faculty member and invited him often to visit his family at their home. While at the university he continued his education, fulfilling his lifelong desire for a degree in law.

When Pershing arrived at the school there were 90 cadets in the battalion; soon the number was 350. According to chancellor Canfield, no other department was making such rapid growth “or has made a deep impression on the people of the city and of the state.” One of the cadets later recalled that the commander’s bearing and clear, clean-cut commands and masterful control “electrified” the young men. As battalion commander, Pershing drilled his young cadets hard, leading them to a victory in the national drill competition held in Omaha in the summer of 1892. The drill team from Nebraska won recognition, only second to the West Point cadets.

He returned to field duty in 1895, helping to round up groups of Cree Indians and deport them to Canada.

Return to West Point

After a brief assignment in Washington, D.C., Pershing was posted to West Point as an instructor of tactics in June 1897. His time at West Point was not a happy one. His inflexible and gruff manner with the young cadets caused him to be disliked by the students. As a result, the cadets gave him the derisive nickname that evolved into “Black Jack.” It stemmed from his service with the Negro 10th Cavalry in Montana. The nickname stuck and followed him the rest of his life. Along with the students, Pershing was unhappy and wanted to return to a field assignment. He sought help from a friend, George P. Meiklejohn, who was assistant secretary of war. Pershing pleaded with Meiklejohn to let him serve in the coming war with Spain.

The Spanish-American War

At the end of the 19th century, Spain was losing its grip on its colonies in Cuba and the Philippines. Cuban insurrectionists waged guerrilla warfare against Spanish troops who occupied the island. The insurgents sought to wreak economic havoc on the island, thus forcing America into the conflict to protect their many investments in the country. Though America had an official policy of neutrality, there was a growing faction within the country that backed the Cuban rebels seeking freedom from Spain. Events came to a head during the night of February 15, 1898, when the U.S. Navy armored cruiser USS Maine mysteriously exploded and sank in Havana harbor. This horrendous act resulted in the loss of 260 men, forcing the hand of President McKinley—the U.S. was soon at war with Spain.

As a result of the actions in Cuba, Pershing received an order to join the 10th Cavalry and was sent to Cuba. There he took a prominent role in the battles of San Juan and Kettle Hills. The commander of the 10th Calvary, Colonel T.A. Baldwin, said Pershing was “the coolest man under fire I ever saw.” For his bravery in battle, he won the Silver Star and a promotion to captain. It was during the Cuban campaign that he made a lifelong friend, a future president, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt. This connection proved to be key to Pershing’s future.

The Philippines

At the conclusion of the short Spanish-American War, Spain ceded the Philippine Archipelago to the United States under the 1898 Treaty of Paris. The insurrection in Cuba had drawn the U.S. into conflict with Spain, and now the treaty had thrown the U.S. into the middle of another insurgency, this time in the Philippines.

After a brief time in Cuba, the army put Pershing’s law degree to work in the office of the assistant secretary of war. The government wrestled with the problems of governing the newly acquired colonial empire and put Pershing in charge of the Bureau of Insular Affairs, a new division within the War Department. In this position, he helped form early policies of military government for U.S. possessions. In the fall of 1899, his request was granted for duty in the Philippines. It was there that Pershing encountered the real challenges of managing foreign people he had developed policy for in Washington.

In the Philippines, many tribal and religious groups on the islands resisted American rule, just as they had done during the period of Spanish control. The indigenous Muslim Moro peoples were especially troublesome as they were notoriously hostile to Americans. Pershing combined military force and diplomacy in a campaign around Lake Lanao to crush the Moro resistance on Mindanao. His accomplishments were recognized by the Army brass, and he was given a promotion for his exemplary performance.

Marriage

In February 1905, Pershing married Frances “Frankie” Warren, daughter of Senator Francis Warren of Wyoming. Senator Warren, a decorated veteran of the American Civil War, served as chairman of the Military Affairs and Appropriations Committee. From their apparently happy marriage came four children in rapid succession.

In 1914, General Pershing received command of the prestigious U.S. Army post Presidio in San Francisco. The developing crisis with Mexico along the southern border cut his time in California short. He was assigned to Fort Bliss at El Paso Texas, to handle the unstable situation with America’s southern neighbor. While he was at Fort Bliss, he left his family—now consisting of Francis; three daughters, Helen, Anne, Mary; and a son Warren—at the Presidio.

On the morning of August 27, 1915, a reporter from the Associated Press called General Pershing’s headquarters to confirm a story coming over the wire about a house fire at the Presidio the night before. The reporter believed he was talking to Pershing’s military aide on the phone and asked matter-of-factly if he could get a quote from Pershing’s office about the fire. Rather than talking with an aide, the reporter was speaking to General Pershing himself, who demanded, “What fire? What has happened?” The reporter then gave the general the dire news that he had lost his wife and three of their four children in a late-night fire at their home on the base. Only their six-year-old son, Warren, survived. The news devastated the loving husband and father. He later commented that if it would not have been for the survival of his son he would have gone “nuts.”

The Crisis With Mexico

Mexico underwent a power struggle after the decades-long regime of President Porfirio Días came to an end in 1911. With no clear successor, factions within the country began seeking to fill the power vacuum and not always through peaceful means. One of the chieftains seeking control was Francisco (Pancho) Villa, part Robin Hood, part patriot leader, and part murderous assassin. Pancho controlled much of the region in northern Mexico that adjoined the United States. Villa wanted to draw America into the internal conflicts of Mexico, if not an outright civil war, in hopes he would be the beneficiary.