The blond, dreadlocked German to my left is on the verge of tears. And perhaps a grand mal seizure. “Oh, mein Gott, oh, mein Gott,” he says, hyperventilating as he jumps up and down, his sandaled feet hitting the floor with a series of thuds. In his hands: a small camcorder, which he desperately tries to keep steady while catapulting himself into the air. The footage he’s capturing will surely be unwatchable, beyond the corrective capabilities of even the most advanced image-stabilization tools. But right now it doesn’t matter. My overly enthused neighbor, one of more than 60,000 frenzied fans who have traversed the globe to attend the Star Wars Celebration in Anaheim this past April, is about to have his mind blown.

This annual gathering of the sci-fi franchise’s most fervent followers is the first such event to coincide with a new episode of the space saga in a decade. (Unless you’ve been living on the remote, icy planet of Hoth, you probably know that Star Wars: The Force Awakens is due in theaters Dec. 18.) Celebrants, many of whom camped out in line the night before, file into the Anaheim Convention Center’s auditorium. Some are bearing lightsabers (the ones with the new, surprisingly controversial “crossguard” design) and wearing costumes—or at the very least T-shirts emblazoned with the iconic, bulbous-lettered Star Wars logo. Furry Ewoks, robed Jedis, and way too many dual-bunned Princess Leias to count take their seats. But they won’t stay seated for long. As composer John Williams’s overture, one of the most recognizable motifs in cinematic history, blasts from the sound system, everyone is on his feet. This year’s star-studded, opening day presentation will include appearances by Carrie Fisher, Mark Hamill, and other members of the original cast (Harrison Ford, sadly, is still recovering from a recent plane crash), as well as emerging idols from the new film and its red-hot director, J.J. Abrams.

But the biggest newcomer on stage is the queen of the entire intergalactic Star Wars empire. No, not Padmé Amidala, but Kathleen Kennedy (Most Powerful Women, No. 42).

Kennedy, the president of Lucasfilm and the producer of The Force Awakens, appears from stage right, microphone in hand. Her shoulder-length, light-brown hair is salon-grade shiny. Her smart white blazer and dark, fitted pants are board-meeting-ready. But the rainbow-colored Star Wars logo on her T-shirt gives her just the right amount of understated nerd cred.

“Thank you for the pizzas!” one of the adulating fans yells out. The night before, she and Abrams had ordered pizza for those camped out in line. “You’re welcome!” shouts back the matriarchal leader of this tribe. Three years ago these were George Lucas’s people. They’re now Kennedy’s. Outside of the franchise’s fanboy and fangirl orbit, however—and beyond Hollywood’s inner rings—the longtime movie producer is far from a household name. She is no Lucas or Steven Spielberg. But she has spent decades making movies with both über-directors. In fact, Kennedy is the most prolific female filmmaker in Hollywood, having produced 77 movies in a nearly 40-year career. Her curriculum vitae is chock-full of sky-high-grossing and critically acclaimed blockbusters: Jurassic Park, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, and Schindler’s List, to name a few. Collectively these movies have raked in more than $11 billion in worldwide box-office sales and garnered 120 Academy Award nominations.

Kennedy’s dream team at Lucasfilm, photographed in July. More than half of her direct reports at the 2,000–person company—including Kiri Hart (seated far left) SVP-Development, who runs the story department—are women.

Kennedy’s dream team at Lucasfilm, photographed in July. More than half of her direct reports at the 2,000–person company—including Kiri Hart (seated far left) SVP-Development, who runs the story department—are women.

TOP ROW, FROM LEFT: Ali Comperchio, Ada Duan, Josh Lowden, Lori Aultman, Rhonda Hjort, Jason McGatlin, Kayleen Walters, Lynne Hale. BOTTOM ROW: (to the right of Hart) Vicki Dobbs Beck, Howard Roffman, Rob Bredow, Lynwen Brennan. NOT PICTURED: Blaire Chaput, Brian Miller, Paul Southern, John Knoll, Mickey Capoferri.Photograph by Joe Pugliese for Fortune

And yet Kennedy has largely remained in the shadows of the very men who helped propel her career forward—most notably Spielberg. In an industry that often spits out women when they hit “a certain age,” Kennedy, 62, is finally coming into her own. Handpicked by Lucas himself, she now presides as president of Lucasfilm, the San Francisco–based company founded by the Star Wars creator in 1971. These days it’s up to her, not Lucas, to restore the once-revered studio, steering it out of a 10-year-long funk. It’s a story line worthy of an elevator pitch: the secretary turned studio boss. A 21st-century Working Girl.

The tale, though, is by no means over. Her task remains a formidable one: returning the franchise to its celebrated roots—making movies that focus on story and character, and less on computer-generated imagery. (One of her first moves: To rework the plotline for The Force Awakens, she recruited screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan, who co-wrote some of the most-beloved earlier episodes of the space saga.)

Kennedy has to prove herself to more than just Jedi-wannabes. Right after he brought her into Lucas-film in 2012, Lucas sold the studio and all its divisions—a special-effects shop and audio production unit, among others—to the Walt Disney Co. (DIS) for $4 billion. Three years later, as the new Star Wars film nears its much-awaited debut, the pressure and expectations are mounting. “This is a $4 billion movie,” Bob Iger, the CEO of Disney, says during a recent phone interview, jokingly referring to the sum he paid for the company. “There is so much riding on this film.”

[fortune-brightcove videoid=4462843164001]

During the recent fan convention in Anaheim, Iger was in the front row, watching Kennedy work the crowd. And he advised the team tasked with putting together a trailer shown at the event—which amassed a record-breaking 88 million views on YouTube in its first 24 hours. “I get involved in certain things because I feel they are important to the company,” says Iger. “As I considered my priorities for the year, this [The Force Awakens] was one of them.”

The wager seems to be well placed. “This has to rank as the most anticipated film in the last 20 years, easily,” says Paul Dergarabedian, a senior analyst with box-office research firm Rentrak (RENT). Other industry watchers, meanwhile, have been raising their ticket sales estimates. Morgan Stanley’s (MS) Benjamin Swinburne wrote in a recent report that he expects the film to be “wildly profitable,” trailing only 2009’s Avatar and 1997’s Titanic. The new Star Wars episode could bring in $650 million in the U.S. alone and $2 billion globally, he predicts—figures within shouting distance of those of most other analysts. That doesn’t count the additional $5 billion in merchandise sales (for branded toys, videogames, and other paraphernalia) expected in 2016 alone, nor does it begin to take into account the multi-year-long pipeline of other Star Wars movies, TV shows, and themed amusement park “experiences” now in the works. In other words, Kennedy has enough projects to keep her busy for years to come—and, quite likely, to make the new Lucasfilm head, who reports to Disney Studios chairman Alan Horn but also directly updates Iger (and the board), an indispensable asset to the parent company.

That’s all the more important in light of ESPN’s slip in the latest quarter. Subscriptions at the money-printing sports network, also owned by Disney, took a “modest” dip, as Iger characterized it in an August call with analysts. (That sent Disney shares down more than 9% in one day.) So the Mouse House could use a new cash cow.

But the rising attention from Disney execs, the press, and would-be Wookiees isn’t something Kennedy is accustomed to, nor something she sought. When I join her backstage at the Star Wars Celebration, she tells me: “I’ve always said that I don’t want to be in front of the camera.”

She’d better get used to it. By year-end, even those who don’t know their Lannik from their Phindians will know who she is. The question will no longer be “Who is Kathleen Kennedy?” but “Why haven’t we heard of her yet?”

Act I: Kathy Meets Steven

Above, with Spielberg during the filming of Empire of the Sun.Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures

Above, with Spielberg during the filming of Empire of the Sun.Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures

Among kennedy’s many unsung claims to fame is one—or rather two—particularly challenging cinematic accomplishments: E.T.’s lifelike eyes.

The 1982 flick about a boy who befriends a stranded alien was Kennedy’s first producing credit. It was also a giant leap from her small-screen roots. After studying telecommunications and film in the mid-1970s at San Diego State University, she snagged a job as the lone female camera operator at a local television station. One day a few years into her TV production career, she went to see a new sci-fi film, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which was written and directed by Spielberg. The film inspired her so much, she says, she dropped everything and headed north to Los Angeles to break into Hollywood movie-making. She called up her former college roommate, an actress who was married to director Robert Zemeckis—and the friend got Kennedy her first interview, with filmmaker John Milius, who was developing Spielberg’s next movie, 1941.

Kennedy landed a not-so-glamorous position: as Milius’s secretary. One of her first tasks was cataloguing his gun collection (the director and Apocalypse Now writer was also a longtime board member of the National Rifle Association). Apparently she had a knack for instilling order—and that caught Spielberg’s eye. “I noticed that John had a very organized office,” Spielberg recalls during a recent phone interview. “I was watching how Kathy handled all of his incoming requests, and I said, ‘Since I’m directing this movie, shouldn’t I have a top-notch secretary?’ ” Spielberg pulled rank and asked Kennedy to work for him.

She didn’t last long as the legendary director’s note taker—mainly because she wasn’t taking any notes. “She was supposed to take minutes at meetings but would spend most of the time talking,” says Spielberg. “I was wondering if this was the protocol for secretaries in Hollywood.”

The Berkeley-born daughter of a superior court judge father and a stay-at-home mom was both practical and creative, and not afraid to speak her mind. Not long after he hired her as a secretary, Spielberg promoted Kennedy, then 26, to be his assistant—a role that was less administrative than it sounds. Then, almost as swiftly, she was named an associate producer. In 1980, when Spielberg began working on E.T.—the idea originated as a sequel to Close Encounters of the Third Kind—he asked Kennedy to co-produce it with him.

“She was supposed to take minutes at meetings but would spend most of the time talking and wasn’t writing anything down. I was wondering if this was the protocol for secretaries in Hollywood.”

—Steven Spielberg

Among her first big challenges: getting E.T.’s eyes to look more human. “There’s a famous saying that they are the windows to the soul,” says Kennedy. “We knew that for E.T. to feel real, you had to have some connection to his eyes.”

Her own eyes are blue, and they light up rapturously when she retells stories from her early days as Spielberg’s producing partner. Her primary role, she recalls in a conversation at Lucasfilm’s San Francisco headquarters, was to make sure that the fantastical vision for each movie could be brought to life. That was how she found herself speeding off to the Jules Stein Eye Institute, a center for ophthalmology research in Los Angeles, in search of some real-world inspiration. In this case: mountains of prosthetic eyes. “They were literally bringing me these drawers full of eyeballs,” she recalls. “You start looking at the irises and the size of pupils and the color of the white around the eye, and you start realizing that there’s so much variety.”

Kennedy persuaded the young woman working at the institute to let her borrow two palettes of “ocular prosthetics,” promising to return them that same day. She hurried back to Spielberg, who was simultaneously shooting a new horror movie. “I go running onto the set of Poltergeist,” says Kennedy. “And we went through the eyes and figured out what combination of colors we wanted for E.T. And then I raced back.” Kennedy asked the young woman at the institute to paint the model for E.T.’s eyes. The woman wasn’t allowed to get paid for doing any outside work, so the quick-witted producer came up with a different plan: Kennedy would furnish her apartment instead out of the film’s budget. “That was our handshake deal,” she says, chuckling at the memory. “And she did an absolutely fabulous job—she found the look, she found the soul.”

E.T. and his emotive blue eyes went on to break box-office records. And Kennedy’s role as Spielberg’s indispensable producing sidekick was sealed. “She and Steven were almost the same person,” says Dennis Muren, a visual-effects pioneer who has worked at Lucasfilm’s Industrial Light & Magic division since 1976 and who collaborated with them on E.T. “Both of them are very emotional, and they want to express themselves through their art.” Spielberg has another explanation as to why the partnership has worked: “I’m Jewish and she’s Irish Catholic, so it was perfect from the get-go.” His more serious reason: Kennedy’s sense of humor. “In a pressure-cooker-like environment—script development or production—it’s a blessing when someone in the middle of a meltdown can find something to make you laugh,” he says. Kennedy, meanwhile, lavishes credit on her mentor, who trusted in her abilities. “I was doing everything, whether it was finding the writer, developing the script, putting the production crew together, finding a storyboard artist,” she says. “Whatever it was that was needed, he’d just say, ‘You do it.’ So it was trial by fire. I just dove in.”

Kennedy’s many creative partners attest to her ability to stay calm when the storm inevitably hits. “If I’m stuck in a Turkish prison, she is my first phone call,” says Kristie Macosko Krieger, a DreamWorks Studios producer whom Kennedy mentored before taking on the top job at Lucasfilm. But her thirst for perfection and dogged attention to detail—fun fact: she arrived at one of our interviews with three pages of her own typed-up notes—can be daunting to co-workers. “You never bring a problem to her that you don’t already have a solution to,” says John Swartz, co-producer of Rogue One, an upcoming Star Wars spin-off movie, and Kennedy’s former assistant. Some who know her well but didn’t want their names mentioned have called her “intimidating” and “controlling.” But mostly, those around Kennedy describe her as an imaginative yet practical multitasker who can get the impossible done—and fast. “Once I’m determined to make a movie, Kathy goes full speed,” says Spielberg. “Sometimes my best advice to her was to slow down.”

That may be the one bit of counsel that neither one of them has heeded. Over nearly four decades the two have made dozens of movies together: The Color Purple, Empire of the Sun, Hook, Munich, and many more. In addition, Kennedy had her own production company on the side: In 1992 she and her husband, producer Frank Marshall—they’ve been married for 28 years and have two daughters together—formed The Kennedy/Marshall Company, through which they’ve made more experimental and critically lauded films, such as Persepolis and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

In the ever-complicated arrangements of Hollywood, Kennedy/Marshall and Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment have also continued to work hand in hand producing movies. In 2011, for example, the two companies collaborated to make a grand biopic of Abraham Lincoln. A year later, when they were wrapping the film, which would eventually be nominated for 12 Oscars and win two, another suitor came calling. It was her old friend George Lucas.

Act II: George steals Kathy from Steven

Kennedy and Lucas (above) confer on the set of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.Courtesy of Lucasfilm Ltd.

Kennedy and Lucas (above) confer on the set of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.Courtesy of Lucasfilm Ltd.

Kennedy and Lucas first met when she was still Milius’s secretary. At that time, Lucas hadn’t yet soured on Tinseltown and was working a few doors down from Milius’s office on the Columbia Pictures lot. In the early 1980s, Kennedy, Marshall, Spielberg, and Lucas banded together to make Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, traveling to Tunisia and Hawaii for shoots and partying along the way. “We were all, you know, a group, a clique, whatever,” says the 71-year-old Lucas in a rare interview at his office at Skywalker Ranch, just north of San Francisco. (The filmmaker no longer has a day-to-day role at the company but still owns the secluded, sprawling piece of land that once housed all of Lucasfilm.)

Eventually, though, Lucas retreated to his Bay Area refuge, and he and the rest of his Raiders crew went off in different professional directions. “Steven is much more of a studio person, and I’m much more of an anti-studio person, so I had my own operation up here,” says Lucas, whose counter-establishment rhetoric—much like his silvery hair—only seems to thicken with age.

But by 2012, even with that protective distance from Hollywood, Lucas was feeling burnt out. With Star Wars, he had created a limitless world of fantastical, intergalactic mythologies. The first trilogy, which debuted in 1977, had blown away cinema-goers and critics, pioneered seemingly impossible special effects, and spawned what is probably the longest-lasting and most loyal fan base in movie history. The second Star Wars trilogy, otherwise known as the prequels, launched in 1999. Those movies made a bundle at the box office (a collective $2.4 billion) but received mixed reviews. Lucas was personally lambasted for over-relying on computer-generated images and bringing one of the most annoying alien characters to life—the clumsy Gungan outcast Jar Jar Binks. The criticism wore on him. And as Lucas checked out, Lucasfilm devolved into a stagnant, though still lucrative, entity that fed off of its intellectual-property revenues—a fattened-up Jabba the Hutt who’d eaten too many Klatooine paddy frogs, if you will. “George was just not enjoying it anymore,” says Muren, the visual-effects specialist.

Act III: Kathy takes over company—and dominates Hollywood

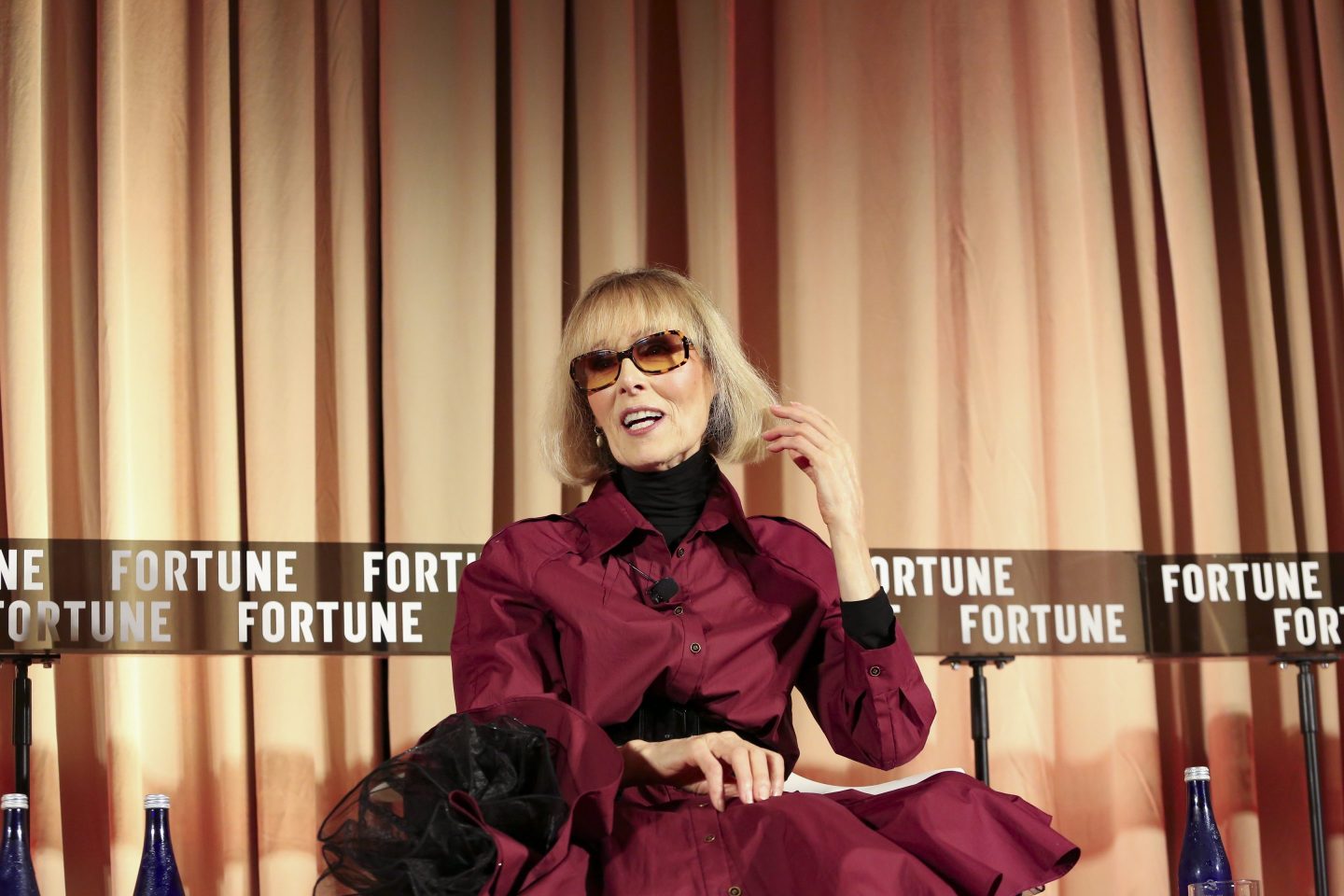

Kennedy, clad in a Star Wars Episode VII jacket at San Francisco’s Presidio, has mentored a number of women in an industry long dominated by men. “If I’m stuck in a Turkish prison, she is my first phone call,” says DreamWorks producer Kristie Macosko Krieger.Photograph by Joe Pugliese for Fortune

Kennedy, clad in a Star Wars Episode VII jacket at San Francisco’s Presidio, has mentored a number of women in an industry long dominated by men. “If I’m stuck in a Turkish prison, she is my first phone call,” says DreamWorks producer Kristie Macosko Krieger.Photograph by Joe Pugliese for Fortune

Lucas knew it was time to do something else—but not before he left his baby in capable hands. At first he struggled to come up with a successor. “I racked my brain to figure out who do I trust and who do I know really well and is level-headed, who understands the business side of it but also understands the creative side of it,” he says. “And finally I banged into it and said, ‘Oh, my God, it’s Kathy.’ ”

To Lucas, Kennedy’s ability to maneuver through studio circles while maintaining high artistic standards may have even surpassed that of his old friend Spielberg. “Steven became powerful enough to where he was pretty much left alone,” says Lucas. “I mean, he never really exercised his power as far as I was concerned, but Kathy learned how to navigate that world very, very well.”

“I racked my brain to figure out who do I trust … who understands the business side of it but also understands the creative side of it. And finally I banged into it and said, ‘Oh, my God, it’s Kathy.’ ”

—George Lucas

In Lucas’s own mind at least, the decision was made. When he invited Kennedy to meet for lunch in New York in April 2012, he asked her if she knew he’d been toying with the idea of retiring. “I thought he wanted to ask me to come up with some names for him,” recalls Kennedy. Once she realized he was offering her the job, she almost agreed on the spot. Lucas, though, first had to call Spielberg. “He wasn’t technically her boss—it was just about friendship,” Lucas says. “It was kind of like, ‘Oh, by the way, Steven, I’m going to marry your wife.’ ” (Lucas says Spielberg was initially in shock but came around quickly. Spielberg says he appreciated the gesture.)

By June 2012, Kennedy was named co-chair of Lucasfilm, initially running the studio alongside its founder. She barely had time to settle in, however, before another big shift came along. Unbeknownst to Kennedy, Lucas was already in talks to sell Lucasfilm to Disney. (He had likewise kept Disney in the dark while negotiating with Kennedy.) His original intention had been to stay on for a few years, as his successor transitioned into the company. He would then release the first film in the new trilogy and sell it off, with her at the helm. But, he says, things moved much faster than anticipated. Lucas, who was about to get married to his second wife and was entertaining the idea of having another baby, was eager to escape the daily grind of running a business. “I realized that I could hold on the extra two years, and maybe make another billion dollars,” he says. “But at that point, when I was 68, I said, ‘Time is more important to me than money.’ ”

By December, the deal was done: Disney had acquired Lucasfilm, Lucas had stepped down, and Kennedy was now president—working for a new boss, Iger. From the start she had a litany of decisions to make. Though she had helped run Amblin and co-created a second production house with her husband, leading an organization the scale of Lucasfilm—with more than 2,000 employees on three continents—was an exponentially harder challenge. On top of that, Kennedy had to transform the company from one “that hadn’t been making movies for some time and that was more of a franchise company into a production company,” says former Industrial Light & Magic president Lynwen Brennan.

Lucasfilm was desperately in need of revitalization. It had become the unchallenged master of CGI, but it seemed to have forgotten how to tell great, original tales. A telling point was that it never had a story department, a group that oversees all aspects of content. So Kennedy created one, bringing in Kiri Hart, a former screenwriter, to build out the group. The idea, as the new boss described it, was to create “a kind of institutional knowledge incubator. If somebody’s working on an animated TV show or a videogame, they [the story group] know what we’re doing on the movie side. Everybody talks to each other.”

A still more pressing task, though, was to rethink the story line that Lucas had sketched out for the new Star Wars episode. Kennedy, frankly, wasn’t thrilled with the plot. Her new bosses at Disney expected the movie to come out in the summer of 2015, but Kennedy held firm that the project would all come to naught without a great story line at its heart. “Every fiber in my being knew what I needed to do to at least get that movie off and running. So that’s what I focused on,” she says. “A lot of what they were expecting was, in my mind, unrealistic, because nobody making the deals makes movies.”

Kennedy quietly began to enlist Abrams—the hot auteur who had made the TV series Lost and the most successful Star Trek movies—as director, along with other filmmaking partners, even before getting approval from Disney. “I just went to them directly, and I made them keep a secret,” she says. Then she went to Disney, telling them, “You’re going to have to trust me, but I need the following people or you will not have a movie.” Her new corporate parent consented.

In the midst of all this came a more prosaic challenge: putting the brakes on company expenses. Kennedy began some modest layoffs, particularly within the animation team, and shut down Lucasfilm’s gaming division. A few executives, like former chief operating officer Micheline Chau, left voluntarily amid the changes. Kennedy appointed another woman, Brennan, in Chau’s stead.

Indeed, the pioneering producer has made a point of hiring and mentoring female managers over the years—more than half of her 18-person executive team, with whom she meets weekly, is female (an anomaly in the movie biz, certainly)—but that said, Kennedy has always been comfortable in a male-ego-driven realm. (Says Lucas: “She was one of the guys.”)

If the decades she spent being the sole woman in the room or on set—or on the playing field—fazed her, she doesn’t let on. Even though the company she now runs has Lucas’s name in it, she is clearly, and confidently, the boss. And if the new Star Wars movie lives up to its hype, she may well be the most powerful woman in Hollywood too.

The skilled water-skier and former quarterback of her seventh-grade football team (yes, a boys’ team) is ready for the big leagues—and knows why she’s here. “If I could throw the ball farther than any of the guys that they were looking at to be the quarterback,” she says, “they wanted me to be the quarterback.”

“You know why?” she asks a moment later, her mouth curling into a badass smile. “Because they wanted to win the game.”

To see the full Most Powerful Women list, visit fortune.com/most-powerful-women.

A version of this article appears in the September 15, 2015 issue of Fortune magazine with the headline “From secretary to studio boss.”