[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

By exporting its “moderate” religious model, Morocco aim to enhance its soft power in Africa. Though, this policy faces competition with the other religious ideologies.

Download article

Executive summary

Within the framework of its soft incursion approach in Africa, Morocco has developed, over the last dacade,a new policyof exporting its experience in “Spiritual Security” to a number of African countries. Such policy has been taken within an ambitious geostrategic vision that aims at strengthening the Kingdom’s political and economic influence in the African continent. Some aspects of Morocco’snew religious policyin Africa are embodied in a number of initiatives launched so far for the purpose of enhancing the Moroccan-African cooperation in the religious sphere. Yet, there still exist various challenges to this policy, particularlythecompetition with other religious authorities in North Africa and the Gulf region, Which by virtue of its enormous material potential and its active networks, has seriously contested the historical spiritual presence of Morocco within a number of West African States.

Introduction

In June 2015, Morocco founded “Mohammed VI Foundation for African Ulemas (Islamic Scholars) with a view to “unifie and harmonise the efforts of the Islamic scholars in Morocco and African countries in order to identify, spread and consolidate the tolerant values of Islam”[1]. At first glance, it might appear that the main objective of this foundation is to harmonize the efforts of the African Islamic scholars in order to address security challenges of extremism and terrorism. However, an in-depth consideration of this objective shows the fact that this initiative is merely one of a structured religious policy that underlay broader geostrategic regional aspirations. Basically, Morocco’s religious policy in Africa serves its wider new Africa-oriented policy and aims at enhancing and expanding its political and economic influence in Africa, beyond what was known as Rabat-Dakar Axis, a traditional limited sphere of the Kingdom’s African-oriented policy for several decades.

Morocco’s plan to export its “Spiritual Security” experience to Africa is a part of a broader strategic vision aimed at contributing to the efforts of countering extremism, promoting peace in the Sahelo-Saharan region, and ultimately anchoring the Kingdom’s regional presence internationally. This ambitious policy faces various challenges that may affect its effectiveness and therefore hinder the successful achievement of its pre-planned objectives and goals.

A new religious strategy at Africa?

At the outset, it should be understood that the new Africa-oriented religious policy is not a spur-of-the-moment move, but it’s an extension of previous religious policies that was developed in mid-1980 and was known as the aleternative or parallel diplomacy. For instance, Morocco’sMinistry of Awqaf (Endowments) organized “The Sufi Schools Conference”, in Fez in 1986, and created “The Rabita (Association) of Moroccan and Senegalese Ulemas” in the same year.However, the new form of diplomacy aimed at breaking out the isolation of Morocco in the continent and remedying its political and diplomatic channels after Morocco’s withdrawal from the African Union in 1984[2].

The significant transformation was articulated by the gradual transition from a “Spiritual Diplomacy” primarily based on Sufi schools as a tool of spreading Moroccan religious policy in Africa to the adoption of a transnational structured religious policy. A policyfounded on a new vision that reflectsthe substantial progress in terms of the intensity of religious work, anddiversifying its operating tools and the actors involved in it, also Re-select areas of intervention and how to employ it.

Intensive and Structured Religious Policy

Morocco have gradually shifted from an occasional, defensive and reactive religious action to a long-term pragmatic offensive religious policy. A policy aims at investing the Moroccan-African joint spiritual heritage in consolidating the establishment of long-term vital strategic partnerships with its African countries. As a matter of fact, there are two indicators of this transition: First, the active dynamic led by the “Imarate Al Muminin” (commander of the faithful), following the King’s frequent visits to various African countries which exceeds fifty visits and covered 29 countries by the end of 2017[3].

Regardless of the pragmatic motivations of these visits – mainly to consolidate Morocco’s political and economic relationships – King Mohammed VI was keen to lead parallel symbolic religious activities and initiatives; notably, performing Friday Prayer in the capitals of some African countries[4]. In this regard, out of 70 Friday Prayers scheduled on official royal activities agenda between 2014 and 2016, 13 prayers were performed in African countries, including Senegal, Mali, Gabon and Nigeria.

In addition to the extensive media coverage of this religious action, the King has consistently handed out thousands of Holy Quran copies, printed by “Mohammed VI’s Foundation For the Publication of Holy Quran”to several mosques in these countries. Moreover, during his visits to some African countries between 2013 and 2014, the King was keen to meet with a number of religious leaders and Sufi sheikhs, who yieldfar-reaching influence in these countries, especially in Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire and Gabon. In this regard, the King received Sheikhs and spiritual leaders of all Tijaniya Sufi families in addition to the representatives of other Sufi schools, especially Al Qadiriya, and Al Maridiya[5].

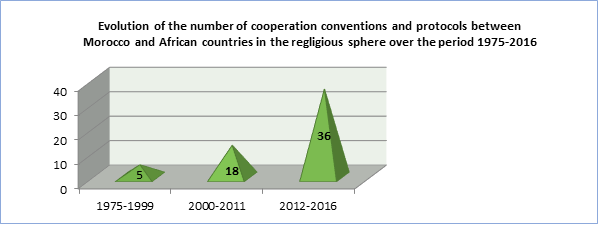

Moreover,the Moroccan-African religious cooperation recordedover the recent yearsan outstanding quantitative and qualitative evolution. By examining the chronological evolutionof the cooperation conventions and protocols concluded between the Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs and its counterparts in the African countries, we find that the number of religious conventions between the year 1975 and 1999 was only 5 conventions. This number increased to 18 conventions between 2000 and 2011, rising drastically to 36 conventions in a five-year period only between 2012 and 2017.

In parallel with this quantitative evolution, the current policy is judged to be more dynamic and rational, as it exploits practical tools and well-structured institutional frameworks. Under this framework, Morocco launched a training program for the African Imams. This program is regulated by legal provisions and bilateral conventions that set forth ad hoc regulations for this cooperation and provide details on its implementation.

Source: author’s compilation

New actors

Furthermore, in addition to the top-down governmental policy, Morocco also mobilisednon-governmental stakeholderstoconsolidatethis policy from bottom-up. In other words, this policy no longer relies on Islamic Sufi networks, known of their strong influence in some West African countries (e.g. Al Qadiriya and Tijaniya Sufi schools), or depends only on the governmental and institutional religious cooperation mechanisms (e.g. Mohammed VI Foundation for the African Ulemas). Instead, the policy embraced new non-stateactors and stakeholders, including the Moderation Forum of Africa and the Association of Maghreb Ulemas, two organs composed of influential Islamic actors and Moroccan Salafists. The Moderation Forum of Africa was established in the Mauritanian capital Nouakchott and embraces a number of popular and official preaching associations and bodies, regardless of the dominance of the Islamist movements, including the Moroccan Movement for Unification and Reform, the Algerian Peace Movement Community, and the Senegalese JamaatIbadar-Rahman (the Community of God’s Servants). Indeed, this initiative reflects the preoccupation of the Movement for Unification and Reform with “the same issues and priorities of the State, despite their different position and mechanisms”. The initiative shows also the willingness “to lay the foundation for the complementarity between the governmental and civil action to counter the security challenges emanated from the Sahelo-Saharan countries…help the State in achieving its objectives successfully and to restore the Moroccan enlightenment in the region”[6].

Pragmatic Investment

The investment in the Africa-oriented religious policy has witnessed a significant evolution. In this respect, the consolidation of joint spiritual and religious relationships no longer represents the sole method adopted by the Kingdom to build new ties with West African States, as was the case in the eighties. On the contrary, over the recent years, the Kingdom has led a new strategy based on maximizing the spheres of economic cooperation and increased the volume of investments and commercial exchange, and diversified its bilateral partnerships with African countries, regardless of their official position on the Moroccan territorial integrity. That is to say, Morocco nowadays considers the spiritual-security cooperation only one of the supportive and complementary pillar of its pragmatic policy that enhances South-South cooperation and diversifies its strategic partnerships in the economic and development spheres with its African counterparts[7], beyond the traditional axis Rabat-Dakar, which used to be the sole determinant of the Moroccan Africa-oriented policy for decades.

Strategic Objectives and Challenges

By the new Africa-oriented religious policy, Morocco tries to achieve three main objectives. The first objective is the ‘pre-emptively’ protecting the Kingdom’s homeland national security. To that end, Morocco’s aim to counter-violent extremism push it to include the export of its ‘spiritual security’ policy not only internally but also in its regional sphere to deal remotely with potential threats to the Kingdom in the future. This proactive policy is based on a decentralised approach that take into account the local religious and sectarian specificities in Africa. This can be achieved by the revival of the traditional local Islamic networks, namely Sufi and Sunni sects, and the maintenance of its structure to encounter religious extremism mind-set.

The Moroccan approach aims to be an alternative to the “Hard approach” (Military strategy) led by the regional States and major Powers for decades in order to restore security and stability in the Sahel region, including the training initiative for the armed forces of the Sahelo-Saharan countries to encounter terrorism, and Operation Serval led by France in Mali in 2013. The two actions doomed to failure, as they couldn’t supress the Jihadist activities and terrorism expansion in the region. Morocco’s new soft approach to counter extremism in the Sahel region was announced in the King’s Speech on the occasion of inaugurating the Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita in September 2013. In his speech, the Kingexpressed clearly the aspects of the palliative approach that Morocco proposes in order to immunise Mali and Sahel countries from instability risks in the future: “Any international initiative for coordination shall be doomed to failure, if it does not take into account the cultural and religious dimensions it deserves”[8].

The second objective of this policy embodies the Kingdom’s attempt to compensate itself for the unachievable Maghreb cooperation that may not be reached at least in the short and medium term. For instance, the regional security cooperation with the Maghreb countries remains low[9], regardless of the efforts made at the regional conference on borders security in North African countries and Sahelo-Saharan region, and in spite of the new dynamic in the Community of Sahelo-Saharan States (CEN-SAD)[10]that aims at finding new ways of security cooperation between the Maghreb countries and their Sahel counterparts.

This lack of cooperation between the Maghreb countries concerns also the religious sphere. In this regard, the official efforts to bridge this gap still have no significance in reality. With the excpetionofthe ineffective joint conference of the Ministers of Awqaf, all other bodies of the Maghreb Union remain empty-shell since their establishment. As a matter of fact, since the establishment of Union in 1989, the Maghreb Ministers of Religious Affairs met only once by the end of September 2012 in Nouakchott. Interestingly, this first meeting made a number of significant recommendations, especially “the establishment of Maghreb Community for Maliki School” and “the Maghreb House of Hadith”, as well as recommendations on strengthening the cooperation between specialised training institutions for preaching and guidance in the Maghreb countries, and the creation of a joint Maghreb Islamic satellite channel[11]. However, these recommendations have not been implemented up to the moment.

Finally, this strategy offers a soft transnational instrument for Morocco in order to break out the isolation and exclusion imposed by Algeria that restored no effort to dominate the Sahel region affairs. To that end, Algeria constantly opposed the inclusion of Morocco in any political, security or military policies for the Sahel region. For instance, during the meeting of the Joint Military Chief-of-staff Committee (CEMOC), which includes four countries: Algeria, Mali, Mauritania and Niger, held in Tamenrast in 26 September 2010; Mali and Burkina Faso expressed their willingness to include other neighbouring Statesfor countering-terrorism – they meant implicitly Morocco – but Algeria decisively rejected the proposal[12].

However, the aggravation of the Libyan Crisis since 2012 deemed to be an excellent opportunity for Morocco to present itself a relevant party that considers the region’s status quo more seriously, as do other Maghreb and Sahel countries. Thus, such religious policy, with a clear security dimension, could help the Kingdom to foster its geostrategic influence in the region. This move shall help Morocco to become an emerging regional power able to bridge the existing gap and contribute therefore to restoration of the regional security and stability in a hot and turbulent region.

In this regard, the Moroccan ambition to be a religious leader in Africa is supported and encouraged by regional and international powers, especially the United States, France and other European countries. At this level, a number of European officials expressed their willingness to consider Morocco as a regional partner of the Mediterranean countries specifically and the international community generally, owing to its political experience and unique approach on countering violent extremism remotely, and the efficiency it proved in dealing with the shortcomings of the security and military strategies. This might explain the participation of Morocco in the Security Council’s Committee for Counter-Terrorism in New York on 30 September 2014[13]to present its experience in countering violent extremism which can be considered as an international recognition of Morocco’s experience in counterterrorism. It can be also understood as an implicit request to export its experience on the regional level in order to consolidate international efforts to restore security and stability in the Sahel and West African regions.

In fact, Morocco is convinced that the security of the Sahelo-Saharan region concerns also the national security of the Kingdom and of the Maghreb region as a whole. Therefore, the issue of security of these two regions should be seen as a cohesive and indivisible unit, and what might threatens one State may inevitably have negative repercussions on the other neighbouring States.From this perspective, the regional religious policy offered by Morocco, though it aims primarily at achieving the special interests of Morocco and strengthening its influence in Africa, it may instead give birth to further cooperation in the field of religious security. In the mid to long term, this may be the first step to enhance the opportunities and give stronger chance to establishsustainable inter-regional security integration between North African and Sahelo-Saharan regions. On the other hand, the African countries, which have startedthe religious cooperation with Morocco, are now either in their political transitionphase, following revolutions or conflicts (Tunisia, Libya and Mali), or in the phase of precautionary policies aimed atprotectingthem from the negative repercussions of the conflicts suffered by the aforementioned States, as is the case of Niger, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal. In either case, one can claim that these countries areawareof the significance and necessity toreform and control the religious field, while making the necessary arrangements to rebuild these countries, taking into considerationthe adoption of realistic, smart and soft approaches different from the previous security-oriented policies.

As forTunisia and Libya, for instance, the two countries endeavour to learn fron the Moroccan experience in reforming the religious sphere with a view to overcome the failures of past experiences, especially the security-oriented approach adopted during the regimes of Ben Ali and Kaddafi to manage the religious field. This might explain the vaccumaftercollapse of these authoritarian regimes that was exploited by jihadist groups to extend their control over religious spaces and intensify their recruitment operations among young people who were religiously weak.

With regard to the case of Mali and other Sahel countries, it seems that Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its supportive terrorist groupsmanaged to infiltratethese countries and exhibitedresilience to recruit fighters and perpetrate terrorist attacks. That was due to the security weakness and the geopolitical fragility of the region, in addition to the vulnerability of religious institutions and censorship imposed on its spaces and its actors[14].This fragility enabled these groups to the penetrate and find a safe haven in that area. Thus, the reform of the religious policies in these countries should be among the pillars to counter violent extremis. This can be done through the establishment of religious institutions and the revision of religious discourses they issuetoensure consistency with sectarianspecificitiesand harmonization of local moderate religious practices and traditions, which representactuallyshared values between the Islam of the Maghreb and the Islam of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Challenges of exporting the “spiritual security” experience to Africa

Nevertheless, Morocco’s main challenge to implement this policy emanate from the fierce competition with theregionalreligious authorities, especially the Gulf States. For a longtime, these countrieshave competed with Morocco’s religious presence in the region and thanks to their ressources, they made more efforts to maximise their expansion and influence in Africa. They spend huge amounts of money in preaching Islam, encouraging education and leading charitable and social works: building hospitals, drilling wells and providingaids to poor people.Moreover, Morocco faces competition from countries in the North African region, mainly the Egyptian Al-AzharUniversity, which is active in Africa[15]through its affiliated networks of educational institutions and mosques that are highly active in countries like Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire. These religious institutions are supervised by accredited scholars and preachers who are directly affiliated to the Al-Azhar.

Likewise, Algeria has toke part in this religious competition. To confront Moroccan actions in Africa, Algeriamobilizedressourcesnot only to compete with Morocco but also mighthinderitsinfluence in this area. In this regard,Algeriaestablished“the Association of Scholars, Imams and Preachers of the Sahel Region” in Algeria in 2013andconstanted attempts to support the Sufi Schools throughmobilisingressources to support leaders of the Tijani School, who are not affiliated with thethe authority of the mother TijaniaorderinFes. And as mentioned earlier, Algeria decisively rejects the involvement of Morocco in any political or military security arrangements or frameworks for the Sahel region.

Conclusion

By sharing its experience in the “spiritual security”, Morocco endeavor to give a push for its new African policy and to strengthen its position and influence in africa. With the growing instability and the increasing of threats of extremism in some countries of the Sahel and West Africa, especially after the fall of the Gaddafi regime, Morocco has succeeded in highlighting its experience in managing religious affairs as a unique success story, andbecame an attractive model that can be inspired to restore security and stability in the region. The active involment ofscores of African countries in Morocco’s religious cooperation programs is a quantitative indicator that reflects to a certain extent this succes. However, this increasing involvement, although its significant, does not necessarily indicate the effectiveness of these cooperation programs, nor does it guarantee the achievement of the desiredoutcomes and objectives set by Morocco.

If it’s early to assess these programs and initiatives, both at the level of instruments and mechanisms of operation or on the level of their proceeds, there is a fundamental and urgent question to ask: to what extent Morocco’s religious activities in Africa is capable of producing religion elites, and care of sheikhs who has a firm loyalty to the kingdom? Given the fact of competitive landscape and sharp polarization that permeates the religious fields of some countries concerned with religious cooperation with the Kingdom, as we have already pointed out. Is Morocco able overcome the challenge of the competing religious authorities by establishing aproactive and effective institutions that is able to strengthen its presence in Africa and confirm its presence in thefield? And in the the opposite case, e.ithe lack of strategic vision for the Moroccan religious work in Africa, the question will be whether this approach is merely a top-down superficial policy supported by marketing and media coverage that lacks real or tangible influence on the ground?

Notes

[1] Article 4 of Dahir (Royal Decree) No.1-15-75, issued on 24 June 2015 on founding Mohammed VI Foundation for African Ulemas, Official Gazette, No. 6372, dated 25 June 2015, folio 5996-6000.

[2] Review: Hmimnat, S., 2018. Religious Policy in Morocco (1984-2002). Casablanca: Africa East.

[3] As per the distribution of His Majesty’s visits during the last sixteen years, please refer back to the Infographic published by the French magazine “JeuneAfrique” on 28 November 2016: http://www.jeuneafrique.com/mag/376906/politique/infographie-mohammed-vi-roi-voyageur/ (accessed 29-12-2016)

[4] For more details on “Royal Prayer” in Africa, see our forthcoming study: Hmimnat, S. (forthcoming). «‘Spiritual Security’ as a (Meta-)political Strategy to Compete over Regional Leadership: Formation of Morocco’s Transnational Religious Policy towards Africa». The Journal of North Africa Studies.

[5] Activities of His Majesty King Mohammed VI, “the Commander of Believers, during his visits to Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire and Gabon”. The portal of the Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs, 28 March 2013: http://www.habous.gov.ma/إمارة-المؤمنين/2865-أمير-المؤمنين-السنغال-الكوت-ديفوار-الغابون-مارس-2013.html (accessed 22/12/2016)

[6]Bilal Etlidi, “The Movement and the Moderation Forum: The Message and Connotations”. Attajdid (Editorial), 6 June 2014: http://www.jadidpresse.com/info.php?info=13808 (accessed 14-12-2014)

[7] Fassi Fihri, I., ed. 2015. Le Maroc en Afrique, La voie Royale. Rabat: Institut Amadeus

[8] See the full speech of King Mohammed VI on the occasion of Inauguration of the new Malian President: www.maroc.ma/ar/جلالة-الملك-يحضر-حفل-تنصيب-الرئيس-المالي-الجديد/أنشطة-ملكية (accessed 22/04/2016)

[9] During his intervention in the 2M TV program “MubasharaMaakum”, Abdelhaq Al Khiyam, the Director of BCIJ, said: “Even Algeria is a neighbouring country and is located in a region surrounded by security tensions and conflicts, it still persists on refusing any security cooperation with Morocco”. He added: “Any lack of cooperation between Morocco and Algeria in the intelligence sphere shall not only menace the security and safety of Moroccan citizen, but also the safety of their Algerian, Tunisian, Libyan and Mauritanian peers”. Refer to: www.2m.ma/ar/news/الخيام-في-مباشرة-معكم-التعاون-الأمني-ممتاز-مع-جميع-الدول-باستثناء-الجزائر-التي-ترفض-التعاون-20170927

[10] The Community of Sahel-Saharan States is a regional organisation that includes 29 African States. It was established in Tripoli, Libya in 1998. It aims at achieving the economic integrity between Member States and meeting the challenges related to the lack of stability, food crisis and desertification in the region. As per the efforts made to revive this community, especially after the death of Muamar Al Qaddafi, the founder, Morocco sought to enter this dynamic. Refer to Benjamin Nickels: Morocco joins the CEN-SAD. Edition Sada (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), January 2013: http://carnegieendowment.org/sada/50491(accessed 7/04/2017)

[11] See “Nouakchott Declaration” issued by the First Meeting of the Maghreb Religious Affairs Ministers (24 September 2012): http://www.maghrebarabe.org/ar/communiques.cfm?id=109(accessed 3/11/2016)

[12]SeeJeune Afrique, 08/10/2010, http://www.jeuneafrique.com/194653/politique/mobilisation-g-n-rale-ou-presque/ (accessed 28/01/2014).

[13]http://www.un.org/en/sc/ctc/docs/2014/Concept_note.pdf (consulted 27/06/2015).

[14] Taking the example of Mali, the management of the religious field and the organisation of activities by the religious associations remained in the hand a directorate annexed to the Ministry of Interior for a long time. However, following the Crisis of 2012, the transitional government created for the first time in the same year the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Rituals.

[15] About this point review :Bava, S. 2014. «Al Azhar, scènerenouvelée de l’imaginaire religieuxsur les routes de la migrationafricaine au Caire», L’Année duMaghreb, n° 11, p. 37-55.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Salim Hmimnat

Salim Hmimnatis a research fellow at the Institute of African Studies – Mohammed V University - Rabat. He has published a number of research papers and studies. His recent book was titled “The Religious Policy in Morocco: State’s Fundamentalism and Challenges of Authoritarian Modernisation”, Afrique Orient Editions, 2018.