Abstract

Owned by British musical theatre composer Andrew Lloyd Webber, the Really Useful Group produces, licenses, records, and publishes his musicals. This synergized approach to the production and distribution of musical theatre established a new model for the industry in the 1980s. RUG’s Asia Pacific division also recognizes the profit potential in an increasingly globalized industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

In the final days of May 2014, the North American tour of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, which was scheduled to open in early June, was suddenly cancelled without warning. As part of the promotional and artistic vision, recognizable figures of popular culture were set to headline the production, including Michelle Williams of the R&B group Destiny’s Child (Mary Magdalene), JC Chasez of *NSYNC (Pontius Pilate), Brandon Boyd of the American rock-band Incubus (Judas Iscariot), and Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols (King Herod). But the tour’s promoter, Michael Cohl, citing a general lack of interest and the likelihood that the show would be unable to recoup its initial costs, put a halt to all operations. 1 The rights to Superstar are owned by Andrew Lloyd Webber’s media company, Really Useful Group (RUG), which also served as the tour’s primary financial backer, and thus set them on a litigated collision course with Cohl, 2 who owns the touring company S2BN Entertainment and is no stranger to large-scale, big-budget musicals, having served as lead producer for several shows, including Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark.

Musical theatre is a business. Companies like RUG exist largely to manage, promote, and commodify musicals on an increasingly globalized scale. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, there have been few more successful than Lloyd Webber’s company. Comparatively, Lloyd Webber and Cohl have each met with different degrees of success in the business of producing major commercial musicals on Broadway and the West End. While this chapter focuses on Lloyd Webber and RUG, it is important to point out that although the companies run by Lloyd Webber and Cohl have each shown strong understanding and implementation of the larger scope of the theatrical commodity—merchandising, cast recordings, videos, tours, etc.—it is Lloyd Webber and RUG that have navigated the international and globalized opportunities with better success. Indeed, RUG (and its earlier manifestation as the Really Useful Company) provides one of the earliest and most successful models of theatre production and commodification in the global market. This chapter will outline the formation of RUG, its growth and diversification, and examine its restructuring of musical theatre as an international globalized commodity, whereby a particular show is maintained as the property of its producer and as such, makes use of transplantable aesthetics, signifiers, characters, themes, and other elements that increase the likelihood of a musical’s success in markets around the world. 3

Any examination of the Really Useful Group must also include within its purview the person most synonymous with the company itself: Andrew Lloyd Webber (b. 1948). Although Lloyd Webber is best known as one of the premier composers of musical theatre, with musicals such as Jesus Christ Superstar (1970), Evita (1978), Cats (1981), The Phantom of the Opera (1986), and others, receiving positive critical reception, demonstrating financial viability, and achieving long runs on the West End and Broadway (with Phantom maintaining the title of the longest-running Broadway musical), it is his company that maintains the success of the musicals he has written and expands their commercial potential in new markets.

Lloyd Webber was born in London into a family well acquainted with the professional worlds of music and theatre as his father worked as a composer and organist, his mother as a violinist and pianist, and his aunt as a professional actress. 4 He attended the prestigious Royal College of Music and by 1970 had met with critical and commercial success as composer for Jesus Christ Superstar. He would collaborate with lyricist Tim Rice on two more musicals, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat (1973) and Evita, and solidify his place as one of the most successful and popular composers of musical theatre in the latter part of the twentieth century. This is due in large part to the growth of new opportunities to capitalize on the success of those musicals and reach into new markets, particularly the recording industry—especially as personal stereo systems were hitting new technological advances in the 1970s and 1980s. For example, Superstar was initially a very popular concept album before it moved to Broadway in 1971. 5 Since then, RUG has maintained the rights to the cast recordings of Lloyd Webber musicals, many of which have gone platinum in the United States and United Kingdom. 6 Thus, he is not just a well-known name because his musicals were popular on Broadway, but also because his songs were heard in living rooms, on personal stereos, and radio stations across the United Kingdom and United States. More recently, established recording artists have been drawn to his musicals, as evidenced by the number of major artists who signed on to the now-defunct tour of Superstar. RUG has even pushed Lloyd Webber musicals into the digital realm with a promotional video that, in October of 2015, premiered some of the music and characters from School of Rock the Musical (2015, and an adaptation of the 2003 film) that hit over one million views in only three days on YouTube. 7

Early on, Rice and Lloyd Webber were represented by New Talent Ventures, a large talent agency that was a step up from their previous representation, 8 and which was eventually purchased by Robert Stigwood and his Robert Stigwood Organization (RSO) after the success of Superstar. RSO was a very diverse company, representing musical talent from composers and artists but also producing musicals and television shows, including the circulation of these between the United States and the United Kingdom. A company like RSO that owned venues, represented talent, and recorded in-house could reduce costs and maximize returns. It proved particularly successful with reinvesting profits from one area of a production into new ventures for that same production, or into other aspects related to the production’s continued profitability and integrity. By using the resources of a diversified company and treating a show like Superstar as a commodity rather than just a work of art, RSO was able to promote the show, mount a touring company around the United States, and fight court battles against pirate productions and unauthorized use of the show’s music, significantly reducing the risk of financial ruin to the company (and Stigwood) as a whole. 9

The potential for Lloyd Webber to profit further from his musicals, and conversely take on more risk, was first realized with the formation of separate companies to manage his business interests. Lloyd Webber never states that he modelled the RUG after Stigwood’s RSO, but as his musicals became more successful, he moved his company in a similar direction. In 1977, Lloyd Webber initially established Escaway to manage his personal finances, Steampower Music Company to manage music publishing, and the Really Useful Company as the producing arm for his musicals. Eventually, in 1985, he brought these, and other companies that oversaw aspects such as tickets, films, and magazines, under one parent company: the RUG.

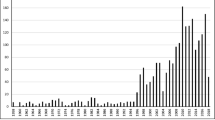

The success of Lloyd Webber’s shows cannot be understated. Since 1979, there has been at least one Lloyd Webber musical running on Broadway, and no other composer can match his international success, as he has had shows running in countries around the world since the early 1980s. 10 But breaking into East Asian markets was what made RUG truly groundbreaking in the international business of musical theatre. In the early part of the decade, Evita and Cats helped the Shiki Theatre Company of Japan (see Chap. 28) to become one of the most prolific producers of Western commercial theatre in Japan and changed the landscape of Japanese theatrical production by making the Western musical a hot commodity in the Japanese entertainment economy. The Shiki Theatre Company translated the shows into Japanese and implemented production elements such as the long-run concept and new technological approaches for ticketing and performances that had made the shows so successful on Broadway. 11 The success of these shows forever changed the Shiki Theatre Company and proved that what made Lloyd Webber so successful was a certain universality within his productions that made transporting them to foreign (particularly non-Western) markets relatively easy, inexpensive, and culturally viable.

The long-term cooperation with the Shiki Theatre Company not only proved the potential of the East Asian markets, but also provided RUG with the necessary capital to venture into other untapped markets in the region. RUG serves as the parent to a number of international offices, set up in countries around the world to protect its interests in a particular state and oversee productions promoted in neighbouring areas. For example, after opening an office in Sydney, Australia, RUG was able to mount a long-running production of Cats in Singapore in 1993 at the Kallang Theatre in a market where local shows never played for more than ten days. Other, more recently popular shows like Phantom soon followed. RUG now has permanent offices located in Singapore, Hong Kong, Sydney, Frankfurt, New York, and Los Angeles, with its head office in London. In 1996, Patrick McKenna, then chairman and CEO of RUG, explained how this model is used to import RUG musicals into global markets:

We’re committed to developing entertainment centers around the world, what we call location-based entertainment. Obviously, apart from developing, we can produce and promote in these locations, offering first-class service to any new live entertainment. For instance, we could take a hit show from the U.S. and promote and exploit it around the world in our venues, backed up by our branch offices. 12

These branch offices are not the only example of the presence of RUG around the world. Building and purchasing theatres has been part of the RUG model since the 1980s. Some of these theatres have been purpose-built for Lloyd Webber shows, such as the Starlighthalle in Bochum, Germany where Starlight Express (1984) has been playing since 1988 and is the longest running musical in German history. Although now owned and managed by Mehr! Entertainment, the Starlighthalle has helped cultivate a love for Lloyd Webber musicals in Germany since the late 1980s and provided the financial capital for its owner and manager, Maik Klokow, to continue bringing Lloyd Webber musicals into the country. In addition, RUG also owns and operates six West End theatres. The theatrical landscape from Broadway to the West End to Asia has been and continues to be shaped by the presence of Andrew Lloyd Webber. Through the ownership and management of theatre buildings RUG is able to expand the musical experience beyond the stage and throughout the building via gift shops, playbills and ticket counters, and areas for food and drinks. Creating an experience within these theatres in markets around the world is what McKenna meant through his use of the term ‘location-based entertainment’. 13 The entire location is a part of the performance. Thus, RUG imports not only the Lloyd Webber musical, but also the potential to participate, through the process of capital exchange, in the culturally and socially signifying involvement with the musical as an expanded commodified phenomenon. 14

But the success of globalization to open up the business of musical theatre to new markets has also resulted in new approaches for RUG. In the West End in 2002, as his first production where he served solely as producer and in no other capacity, Lloyd Webber attached his name to the musical Bombay Dreams as a means of introducing more non-Western concepts into the musical theatre form and hoped to capitalize on the growth of Bollywood and its aesthetic styles outside of South Asia. 15 But to be successful in a Western market, the Indian cultural aspects of the production were appropriated into the predominantly Euro-American musical form. The show was advertised on the marquee of the Apollo Victoria Theatre as ‘Andrew Lloyd Webber presents A. R. Rahman’s Bombay Dreams’, and Lloyd Webber even seemed uncertain about potential audience reception when he first signed on to the project, stating that ‘It will be an extension of Indian culture presented in English to a wider audience’, and, ‘We have to laugh with the show and not at it.’ 16 The show met with a mixed critical response, achieved mild financial success in its London run, and, perhaps in a tacit yet business-savvy understanding of the difficulty of producing the show in markets without a large Indian diaspora population, 17 RUG only put up the money for one-seventh of the production costs of moving the show to Broadway in 2004. Upon the show’s move to Broadway, Lloyd Webber remarked upon the cultural distinctions of the West End production stating, ‘We thought we needed to spend a little more time tipping our hat to certain Bollywood traditions. We probably tipped our hat too much.’ 18

The model of location-based entertainment, used to import Lloyd Webber musicals around the world, also seemed to play an important role in bringing Bombay Dreams to the West End and Broadway. Notably, the move to Broadway appeared to be more difficult and many aspects of the show were changed. How to define the experience of attending Bombay Dreams for Broadway audiences became the focus of the show’s move from the West End. As the lead production company, Waxman Williams Entertainment sought to bring in non-Asian audiences as quickly as possible. 19 The conclusion of the musical’s narrative was changed so that the show ended on an upbeat note, certain songs were jettisoned or rewritten, and marketing strategies were employed in the poster design and show tagline to highlight the exotic nature of the show’s locale, but appealing specifically to Western audiences. 20 It is unclear how many of these changes were precipitated by Lloyd Webber and RUG, despite their reduced role in producing the show, but Lloyd Webber certainly recognized the cultural and racial lines along which this show attempted to balance itself and felt that reception from a primarily white audience would be key to the show’s success. 21 In what became, perhaps, a recognition of the importance of a largely white audience to the show’s long-term success, Lloyd Webber maintained the Broadway changes to the production in a remount for the West End. 22

Despite mixed reviews and a mildly successful run, 23 Bombay Dreams serves to bring RUG’s business model of musical theatre in a global context full circle. RUG was the company with enough clout and capital to stage the work of an Indian artist unfamiliar to most audiences outside of India and the Indian diaspora. In doing so, RUG’s business model hinged upon the familiarity of the Lloyd Webber brand for Western audiences and the management of the cultural borderline as a means to market the production. It imbued Bombay Dreams with the conventions of West End and Broadway musical theatre, which resulted in defining Rahman’s production as successful or unsuccessful along this cultural borderline. This borderline occurs as a result of the globalizing process where the multinational corporation attempts to ‘adopt’ or give agency to a seemingly foreign cultural commodity. Jerri Daboo, in her article ‘One Under the Sun’, states that ‘in the case of Bombay Dreams, [the] portrayal is a homogenized, stereotypical vision of “Indian,” conforming to an imperialist definition of ethnicity’. 24 She goes on to provide insight into the problematic portrayal of capitalist ideals in the production, especially within the historical and postcolonial context of the Anglo-Indian relationship. RUG uses this intersection of appropriating Indian cultural aesthetics into a business model reliant on musical theatre as a commodity developed in the crucibles of the West End and Broadway. In this way, it is apparent that, for RUG, importing musical theatre into particular cultural markets (whether it is Evita and Cats to Japan or Bombay Dreams to the United States) relies on the global recognition of the Lloyd Webber brand and the manicured cultural experience within which the audience feels comfortable participating.

The popularity of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musicals and the success of RUG around the world still make them leaders in the business of musical theatre. RUG has the expertise and capital to turn a potential flop into a more profitable product through its international reach. The ‘sequel’ to Phantom, Love Never Dies, opened in the West End in 2010 and, after a harsh critical response, 25 moved to Melbourne, Australia for a substantial overhaul that met with wider praise and a subsequent DVD release before moving on to Asian and European markets. 26 But recently, the company has shifted, along with much of Broadway, into adapting popular films as stage musicals and opened School of Rock the Musical in December 2015. Lloyd Webber even supplemented the film’s songs with several original songs of his own, as if to claim it for his brand. It would seem that RUG now sees more potential profitability and success in building on the existing cultural capital of popular films and, like in the ill-fated tour of Superstar, popular recording artists. But it is certain that the lessons learned by Andrew Lloyd Webber and RUG in decades of bringing musical theatre to audiences around the world has positioned them as leaders in creating a financially viable musical theatre commodity, no matter where the market may be.

Notes

-

1.

Dave Itzkoff, ‘Anger for “Jesus Christ Superstar” Cast, and a Black Eye for Its Promoter’, New York Times, 31 May 2014, http://nyti.ms/1kvytC0. In the article, Cohl is quoted as saying that ‘it just did not make business sense to continue, and we didn’t want the cast to endure playing to disappointing audiences’, and that the cost of the production was estimated to be ‘eight figures’. See also Ray Waddell, ‘Why Jesus Christ Superstar Flopped’, Billboard 126, no. 19 (14 June 2014), 12.

-

2.

Dave Itzkoff, ‘No Turning the Other Cheek: Suit Over Canceled Tour of “Jesus Christ Superstar”’, New York Times, 29 July 2014, http://nyti.ms/1tp29pe. According to Itzkoff’s article, the chief executive officer of the Really Useful Group, Barney Wragg, placed the blame for the cancellation solely on Cohl.

-

3.

Dan Rebellato, Theatre & Globalization (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 40–6. Rebellato refers specifically to the musicals of Lloyd Webber and Cameron Mackintosh as ‘McTheatre’ to highlight the emphasis these producers give to providing audiences with as near identical an experience for a particular musical regardless of where it may be seen.

-

4.

See Michael Walsh, Andrew Lloyd Webber: His Life and Works (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989), 15–33 for an excellent biography of Lloyd Webber’s early life. See also John Snelson, Andrew Lloyd Webber (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 5–10.

-

5.

Walsh, Andrew Lloyd Webber, 61–2 describes endorsement of Superstar by Catholic and Anglican leaders as a means to retain religious relevancy amongst an increasingly secularized youth culture.

-

6.

The list of cast recording albums to go platinum in the United States, United Kingdom, or both includes Superstar, Evita, Cats, and Phantom. Lloyd Webber also won Grammy Awards for Best Cast Show Album for Evita and Cats.

-

7.

‘School of Rock’s 360 Video Surpasses 1 Million Views on YouTube & Facebook in Less Than Three Days’, Broadwayworld.com , 17 October 2015, http://www.broadwayworld.com/article/SCHOOL-OF-ROCKs-360-Video-Surpasses-1-Million-Views-on-YouTube-Facebook-in-Less-Than-Three-Days-20151017.

-

8.

See Stephen Citron, Stephen Sondheim and Andrew Lloyd Webber: The New Musical (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 145.

-

9.

See Walsh, Andrew Lloyd Webber, 73–5 for a detailed description of the ways in which Stigwood managed his company’s control of Superstar.

-

10.

See Snelson, Andrew Lloyd Webber, 2–4 for a comprehensive list of Lloyd Webber musicals running concurrently by year from 1983 to 1997.

-

11.

See ‘Musicals’, the Shiki Theatre Company, http://www.shiki.jp/en/musicals.html, for the company’s description of the impact of these musicals on the company.

-

12.

Nigel Hunter, ‘And Now For Something Really Useful …’ Billboard 108, no. 42 (19 October 1996): 38–42.

-

13.

For more on location-based entertainment see Al Lieberman and Patricia Esgate, The Entertainment Marketing Revolution: Bringing the Moguls, the Media, and the Magic to the World (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times/Prentice-Hall, 2002), 269–96.

-

14.

For the capital potential in linking the consumer with the artist/artwork in a ‘creative process’ see Roger McCain, ‘Defining Cultural and Artistic Goods’, in Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, vol. 1 (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006), 160–1; see also chapter 14 by B. A. Seaman, ‘Empirical Studies of Demand for the Performing Arts’, in the same volume.

-

15.

See Stephen Farrell, ‘Lloyd Webber Rides the Boom to Bollywood’, Times (London), 9 March 2000.

-

16.

Quoted in Farrell, ‘Bollywood’.

-

17.

Michael Riedel, ‘Knock on Bollywood—“Dreams” May Come for Musical on B’Way’, New York Post, 27 November 2002.

-

18.

Quoted in Zachary Pincus-Roth, ‘The Extreme Makeover of “Bombay Dreams”’, New York Times, 18 April 2004, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/18/theater/theater-the-extreme-makeover-of-bombay-dreams.html.

-

19.

Pincus-Roth, ‘Extreme Makeover’.

-

20.

Ibid.

-

21.

Pincus-Roth quotes Lloyd Webber as having stated that a ‘white audience … want[s] it to work, embracing the thought that it is musically from a different culture’, in ‘Extreme Makeover’.

-

22.

Pincus-Roth, ‘Extreme Makeover’.

-

23.

Jesse McKinley, ‘Broadway Bloodletting’, New York Times, 9 December 2004. For a summary of the lack of positive critical reception see Riedel, ‘“Dreams” Dashed as Parade Passes By’, New York Post, 11 May 2004.

-

24.

Jerri Daboo, ‘One Under the Sun: Globalization, Culture, and Utopia in Bombay Dreams’, Contemporary Theatre Review 15, no. 3 (2005), 331.

-

25.

See Michael Billington, ‘Love Never Dies’, Guardian, 9 March 2010, http://gu.com/p/2ffhn/sbl. Billington’s review was perhaps one of the most positive when the show first premiered (giving it three out of five stars), yet the apprehension of the show’s success and its significant deficiencies clearly tempered any praise. Furthermore, the amount of negative press caused potential Broadway backers to lose interest; see Patrick Healy, ‘“Love Never Dies” Looking Less Likely for Broadway This Season’, New York Times, 31 August 2010, http://nyti.ms/1nSgPx9. There also exists a website entitled ‘Love Should Die’ at loveshoulddie.com, where the creators aggregate various negative reviews and experiences associated with the show.

-

26.

See Jason Blake, ‘Ravishing Sequel Brings More Anguish for the Phantom’, Sydney Morning Herald, 30 May 2011, http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/stage/ravishing-sequel-brings-more-anguish-for-the-phantom-20110529-1faob.html#ixzz3yanqXjjR. After a more positive reception in Australia, RUG began to aggregate the positive reviews for the show on its website at http://www.reallyuseful.com/press-reviews/love-never-dies-melbourne-reviews/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Thomas, K.A. (2017). Laying Down the RUG: Andrew Lloyd Webber, the Really Useful Group, and Musical Theatre in a Global Economy. In: MacDonald, L., Everett, W. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Musical Theatre Producers. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-43308-4_32

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-43308-4_32

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN: 978-1-137-44029-7

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-43308-4

eBook Packages: Literature, Cultural and Media StudiesLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)