Trotsky's grandson recalls ice pick killing

- Published

It's 75 years since Trotsky, already expelled from the Soviet Communist Party and exiled, went to start a new life in Mexico. But he was hunted down in Mexico City by Stalinist assassins, as his grandson, who was living with him when he died, recalls.

To some people Leon Trotsky was the true hero of the Bolshevik revolution. To others he was one of the most dangerous men of his era.

But to his grandson, Esteban Volkov, he was a father figure who brought the young boy rare moments of happiness and stability at a time of family turmoil and political persecution.

"I was constantly changing father and mother figures," says Volkov, 86. With "the Old Man", as he affectionately calls his grandfather, "I finally found something stable, though it did not last very long."

Speaking from the house in Mexico City where he lived with the exiled revolutionary and his second wife, Natalia, for more than a year before Trotsky's assassination on 20 August 1940, Volkov recalls his excitement at arriving in the Americas from Europe.

He was just 13 years old and had spent most of his childhood moving from one country to the next with his mother Zinaida, Trotsky's daughter, seeking refuge from Stalin's persecution.

"Mexico was an absolute change, it was full of colour, full of sun, so unlike Europe," he says. "I began going to school by myself, on foot. No-one at school knew who my family was."

Life in his grandfather's large and well-guarded home in the leafy Coyoacan neighbourhood was "full of excitement," he says.

Trotsky would spend his days writing at his desk, being interviewed by visiting journalists, or debating politics with the foreign activists and bodyguards who lived with the family.

At meal times, the young boy would listen keenly to the jokes and the heated discussions around the table. But his grandfather would sternly warn the others - do not talk politics in front of the boy.

"All his family had been assassinated, or died because of politics, and I think he wanted his grandson to survive." Volkov's father, Trotsky's son-in-law, had been sent to the gulag in the 1930s. Zinaida had committed suicide when they lived in exile in Paris.

Volkov recalls his grandfather rising early each morning to tend his plants and animals before retiring to his study.

"I would help him feed the rabbits and the chickens, and water the corn," he says. They spoke in French, since the boy had lost his command of Russian, his mother tongue.

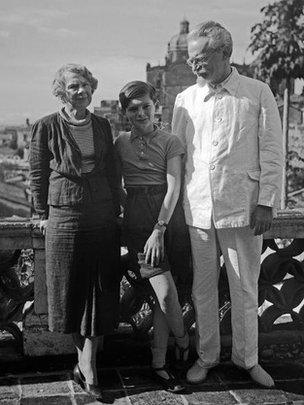

Esteban Volkov has turned his home into a museum to his grandfather

They would also make regular trips out of the city, with all the family and their friends piling into a caravan of cars, heading for the countryside. Once there, the "Old Man" would spend hours searching for cactii or chatting to the Mexican peasants about their lives.

For Volkov, these were days of relative normality, and of a family life that he had previously not known. But it would soon come to an abrupt end.

At 04:00 on 24 May 1940, the young boy awoke with a jolt. As gunmen sent by Stalin stormed the house, the boy threw himself from his bed and hid in the corner of his bedroom. With bullets flying around his room, Volkov was hit in the foot. Trotsky's guards fought back and the attackers fled.

Trotsky and Natalia survived unhurt. "Was I scared? At the beginning yes, but once we heard the voice of my grandfather, full of life, well, it's hard to describe our happiness at having escaped Stalin's attackers."

Afterwards Trotsky rarely left the house and security was stepped up, with more guards and more weapons. The trips to the countryside were abandoned. "I quickly became used to living in those conditions."

But the question on everyone's mind was where would the next attempt on Trotsky's life come from?

The events of 20 August 1940 have been etched into the memory of Esteban Volkov. That was the day that Ramon Mercader, a Stalinist agent of Spanish origin who had infiltrated Trotsky's household, fatally wounded the former Bolshevik leader by striking his head with an ice pick.

Speaking slowly, careful not to leave out any detail, Volkov recounts how he was walking home from school when he first noticed that the door of the house was open and a police car was stationed outside. Filled with trepidation he rushed into the house, to find the guards in disarray.

Before being shooed away, Volkov caught sight of his grandfather, lying on the floor of his study, bleeding profusely. Natalia was at his side. "Don't let the boy see this," Trotsky is reported to have told her. He died the next day in hospital.

The young boy was so distraught he refused to go to his grandfather's funeral. "It was a very, very lonely atmosphere in the house after that."

Following Trotsky's death, Volkov continued living in Mexico with his grandmother. He went to university, trained as a chemist, married and raised four daughters of his own - a great comfort to Natalia as she mourned her murdered husband.

Natalia died in January 1962. Volkov, himself now a widower, has turned the old family house into a museum. It was, he says, his "duty" to honour the memory of his grandfather.

Esteban Volkov was talking to Witness on the BBC World Service